Sutro Baths

37°46′48″N 122°30′49″W / 37.78000°N 122.51361°W

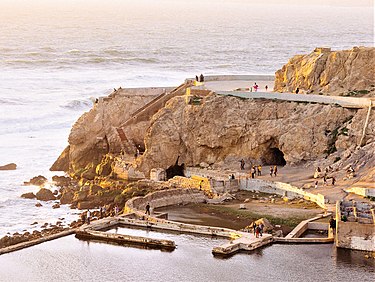

The Sutro Baths was a large, privately owned public saltwater swimming pool complex in the Lands End area of the Outer Richmond District in western San Francisco, California.[1][2]

Built in 1894, the Sutro Baths was located north of Ocean Beach, the Cliff House, Seal Rocks, and west of Sutro Heights Park.[1] The structure burned down to its concrete foundation in June 1966; its ruins are located in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and the Sutro Historic District.[3]

History

[edit]On March 14, 1896, the Sutro Baths were opened to the public as the world's largest indoor swimming pool establishment. The baths were built on the western side of San Francisco by wealthy entrepreneur and former mayor of San Francisco (1894–1896) Adolph Sutro.[2][4]

The structure was situated in a small beach inlet below the Cliff House, also owned by Adolph Sutro at the time. Both the Cliff House and the former baths site are now a part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, operated by the United States National Park Service. The baths struggled for years, mostly due to the very high operating and maintenance costs. Eventually, the southernmost part of the baths was converted into an ice skating rink, with a wall separating it from the dilapidated swimming pools,[5] until 1964 when the property was sold to developers for a planned high-rise apartment complex.

In addition to financial struggles, the Sutro Baths became the focus of a significant civil rights battle in 1897. John Harris sued Adolph Sutro after being denied entry to the baths because of his race. Harris won the case, making it a landmark victory against racial segregation in public facilities. This case set an important precedent for future civil rights actions, underscoring the growing demand for equal treatment and access to public spaces.[6]

A fire in 1966 destroyed the building while it was in the process of being demolished. All that remains of the site are concrete walls, blocked-off stairs and passageways, and a tunnel with a deep crevice in the middle. The cause of the fire was determined to be arson. Shortly afterwards, the developers left San Francisco and claimed insurance money.[7][1]

Infrastructure and facilities

[edit]The following statistics are from a 1912 article written by J. E. Van Hoosear of Pacific Gas and Electric.[8] Materials used in the structure included 100,000 square feet (9,300 square meters) of glass, 600 tons of iron, 3.5 million board feet (8,300 m3) of lumber, and 10,000 cubic yards (7,600 cubic meters) of concrete.

During high tides, water would flow directly into the pools from the nearby ocean, recycling the two million US gallons (7,600 m3) of water in about an hour. During low tides, a powerful turbine water pump, built inside a cave at sea level, could be switched on from a control room and could fill the tanks at a rate of 6,000 US gallons a minute (380 L/s), recycling all the water in five hours.

Facilities included:

- Six saltwater pools and one freshwater pool. The baths were 499.5 feet (152.2 meters) long and 254.1 feet (77.4 m) wide for a capacity of 1.805 million US gallons (6,830 m3). They were equipped with seven slides, 30 swinging rings, and one springboard.

- A museum displaying an extensive collection of stuffed and mounted animals, historic artifacts, and artwork, much of which Sutro acquired from the Woodward's Gardens estate sale in 1894[9]

- A 2700-seat amphitheater, and club rooms with capacity for 1100

- 517 private dressing rooms

- An ice skating rink

The baths were once served by two rail lines. The Ferries and Cliff House Railroad ran along the cliffs of Lands End overlooking the Golden Gate. The route ran from the baths to a terminal at California Street and Central Avenue, now Presidio Avenue.[10][11] The second line was the Sutro Railroad, which ran electric trolleys to Golden Gate Park and downtown San Francisco. Both lines were later taken over by the Market Street Railway.[12]

In popular culture

[edit]- Media stored by the Library of Congress as part of the "American Memory" collection and available for viewing online:

- Sutro Baths, no. 1 and Sutro Baths, no. 2, filmed in 1897 by Thomas A. Edison, Inc.[13][14]

- Leander Sisters, The Yellow Kid dance[15]

- Panoramic view from a steam engine on the Ferries and Cliff House Railroad line route along the cliffs of Lands End, starting at the Sutro Baths depot, filmed in 1902 by Thomas A. Edison, Inc.[11]

- Panoramic view from the beach below Cliff House at Sutro Baths, filmed in 1903 by American Mutoscope and Biograph Company.[16]

- The climax of the film The Lineup was shot at the ice skating rink in 1958.[17]

- A scene from the film Harold and Maude was shot at the ruins of the Sutro Baths.

- Some parts of Earthquake Weather, the last piece of the Fault Lines Trilogy by Tim Powers, are set in and near the Sutro Baths.

- Part of the 2019 fantasy novel Middlegame by Seanan McGuire is set in the Sutro Baths.

- Key scenes from the Cory Doctorow young adult novels Little Brother and Homeland are set in the ruins of the Sutro Baths.

Ruins gallery

[edit]-

Ruins, 2016

-

Ruins, 2017

-

Ruins looking South with Cliff House in distance, Seal Rocks to right, 2018

-

Sutro Baths, 2021

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Staff. "Golden Gate: Sutro Baths History". National Park Service. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Staff. "The History and Significance of the Adolph Sutro Historic District" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ Staff. "Sutro Historic District". Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ Staff. "Sutro Baths History". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ "Sutro Baths" (Search for "Click above for a photographic tour of Sutro Baths", see slides 49, 50 and 51 Archived 2019-02-27 at the Wayback Machine) Cliff House Project

- ^ "John Harris Sues Adolph Sutro for Discrimination". National Park Service. Retrieved November 6, 2024.

- ^ Glassburg, Max (September 30, 2016). "The Dramatic History of San Francisco's Sutro Baths". The Culture Trip.

- ^ Van Hoosear, J. E. (September 1912). "'Pacific Service' Supplies the World's Largest Baths". P.G.&E. Magazine. Archived from the original on 2016-07-01. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ^ Hartlaub, Peter (October 30, 2012). "Woodward's Gardens comes to life in book". SFGate. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ^ "The Ferries & Cliff House Railway" Archived 2017-08-05 at the Wayback Machine Cable Car Museum San Francisco

- ^ a b "Search results for Before and After the Great Earthquake and Fire: Early Films of San Francisco, 1897 to 1916". The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2016-08-23. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ^ "Sutro Railroad" Archived 2017-08-05 at the Wayback Machine Market Street Railway

- ^ "Search results for Inventing Entertainment: The Early Motion Pictures and Sound Recordings of the Edison Companies, Edmp 1425". The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2007-03-02. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ^ "Search results for Inventing Entertainment: The Early Motion Pictures and Sound Recordings of the Edison Companies, Edmp 0005". The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2007-03-02. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ^ Leander Sisters, Yellow Kid dance. The Library of Congress (Motion picture). Edison Manufacturing Co. 1897. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ "American Memory". The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2017-08-05. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ^ "The Lineup (1958)". IMDB. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

External links

[edit]- NPS−Golden Gate National Recreation Area: Visiting Lands End

- NPS-GGNRA: Lands End History and Culture

- NPS-GGNRA: Vestiges of Lands End — digital guidebook.

- NPS-GGNRA: Sutro Bath and Cliff House webpage[dead link]

- Sutro Baths Photographs

- Former buildings and structures in San Francisco

- Former public baths

- Golden Gate National Recreation Area

- Ruins in the United States

- Swimming venues in San Francisco

- Demolished buildings and structures in California

- Landmarks in San Francisco

- History of San Francisco

- Richmond District, San Francisco

- Buildings and structures completed in 1886

- Buildings and structures demolished in 1966

- 1886 establishments in California

- 1966 disestablishments in California

- Public baths in the United States

- 1966 in San Francisco