S 9 (Abydos)

| S9 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Neferhotep I(?) | |

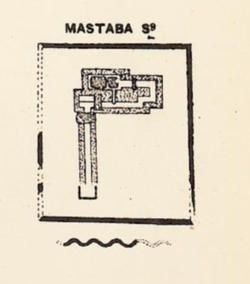

Plan of tomb S9 as drawn by Ayrton, Weigall and Petrie, who thought it was a mastaba | |

| Coordinates | 26°10′17″N 31°55′30″E / 26.17139°N 31.92500°E |

| Location | Abydos, Egypt |

| Discovered | 1901–02 |

| Excavated by | |

| Layout | Enclosure wall surrounding subterranean chambers, now exposed, possibly once capped by a pyramid |

S 9 (also Abydos-south S9) is the modern name given to a monumental ancient Egyptian tomb complex at Abydos in Egypt. The tomb is most likely royal and dates to the mid-13th Dynasty, during the late Middle Kingdom. Finds from the area of the tomb indicate that S9 suffered extensive, state-sanctioned stone and grave robbing[1] during the Second Intermediate Period,[2] only a few decades after its construction, as well as during the later Roman and Coptic periods.[3] Although no direct evidence was found to determine the tomb owner, strong indirect evidence suggest that the neighbouring and slightly smaller tomb S10 belongs to pharaoh Sobekhotep IV (fl. c. 1725 BC). Consequently, S9 has been tentatively attributed by the Egyptologist Josef W. Wegner to Sobekhotep IV's predecessor and brother, Neferhotep I (fl. c. 1735 BC). According to Wegner, the tomb might originally have been capped by a pyramid.

Description

[edit]Location

[edit]Tomb S9 is part of a royal necropolis dating back to the late Middle Kingdom – Second Intermediate Period, which is located immediately northeast of the causeway leading to the much bigger funerary complex of Senusret III of the 12th Dynasty,[4] close to the ancient town of Wah-Sut and at the foot of the so-called Mountain of Anubis, a natural hill in the form of a pyramid.[5][6] It was first summarily explored by Émile Amélineau and subsequently excavated by Ayrton, Weigall and Petrie in 1901–1902. The tomb was covered in sand and proved to have been heavily disturbed, for example, the stone roof of the subterranean chambers had been plundered.[7]

Layout

[edit]

Tomb S9 comprises the remains of a mudbrick inner enclosure wall,[4] over 45 m × 60 m (148 ft × 197 ft) in size,[6] as well as a section of an outer whitewashed[8] wavy wall in front of the northern side.[9] There, lay a small rectangular chapel of which only one course of bricks survives,[4][10] and beyond the entrance to the substructures.[6] The overall layout of the tomb complex is very similar to that of the Southern Mazghuna pyramid.[4]

The substructures were dug into the hard sand, some 3.0 m (10 ft) below the surface, and lined with smooth limestone blocks. A passage leads to a quartzite portcullis, intended to stop tomb robbers from reaching the burial chamber.[11] Beyond the portcullis was a stone-lined chamber 2.1 m × 3.0 m (7 ft × 10 ft) in dimensions, the floor of which hid a further passage blocked by two portcullises, one of limestone and another of quartzite. Beyond, lies the burial chamber housing a massive sarcophagus built from three blocks of quartzite sandstone, roughly hewn on the outside, but well polished on the inside.[9] The southern end of the burial chamber also had a recess meant to hold grave goods.[9] Overall, the plan of the substructures of tomb S9 is similar to those found in the Pyramid of Khendjer.[4] Small fragments of burned wood were uncovered there during the 1901 excavations suggest that the wooden coffin of the king was destroyed.[9] Since then, burned bandages, small pieces of inscribed, gilded plaster from the king's mummy mask, and pieces of wood and faience inlay, stone jars, beads, and bone needles were unearthed in the substructures as well as in the rubbles of the enclosure wall.[1]

Type

[edit]No traces of the superstructures once capping tomb S9 have survived and determining its type—mastaba or pyramid—remains difficult. Ayrton, Weigall and Petrie believed S9 was a mastaba, because of the enclosing wall which they thought would have held the sand packed on top of the substructures.[9] However, the royal nature of S9 and S10 as well as their architectural similarities[4] to pyramids of the late Middle Kingdom in the area of Memphis have led Wegner to suggest S9 might have been a pyramid too.[6] In spite of these arguments, the Egyptologist Aidan Dodson asserts that it is still unclear whether S9 was a mastaba or a pyramid.[4]

Attribution

[edit]

Excavations in 2003 and in 2014 made it very likely that this structure as well as the neighbouring one S10 were originally royal tombs.[12] At the latter date, during excavations directed by Josef W. Wegner of the University of Pennsylvania, a fragment of a funerary tomb stela bearing a relief naming a king Sobek[hotep] was found inside the enclosure of tomb S10, on the eastern side of the complex, where a funerary temple might once have existed.[4] In addition, fragments of wooden coffin inscribed for the same Sobekhotep were uncovered in later Second Intermediate Period tombs adjacent to S10. These fragments indicate a late Middle Kingdom date for the construction of S10. While in early press reports, published just after these discoveries, King Sobekhotep I was named as the possible owner of the tomb,[13] further analyses now indicate that S10 might belong to Sobekhotep IV instead.[14]

Indeed, not only do the fragments of wooden coffin uncovered indicate a late Middle Kingdom date for the construction of S10, but its size means that its owner would have had to reign for long enough to complete it. This only leaves Sobekhotep III, IV, and VI as possibilities, with Sobekhotep IV being the most likely as he enjoyed the longest reign of these three kings. In addition, Sobekhotep IV is the only one of these kings for whom it is known with certainty that he undertook other works in Abydos. As a corollary, tomb S9 likely belongs to Sobekhotep IV's predecessor and brother, Neferhotep I.[14][15] This is perhaps indirectly confirmed by the observation that both Sobekhotep IV and Neferhotep I are known to have been particularly active in Abydos.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b McCormack 2006, p. 26.

- ^ Wegner 2015, p. 71.

- ^ Dodson 2016, p. 57–58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dodson 2016, p. 56.

- ^ Ayrton, Weigall & Petrie 1904, pp. 13–14, pls. XXXVI–XXXVII.

- ^ a b c d Wegner 2015, p. 69.

- ^ Ayrton, Weigall & Petrie 1904, p. 13.

- ^ McCormack 2006, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e Ayrton, Weigall & Petrie 1904, p. 14.

- ^ McCormack 2006, p. 25.

- ^ Ayrton, Weigall & Petrie 1904, pp. 13–14.

- ^ McCormack 2006, pp. 23–26.

- ^ Times Live 2014.

- ^ a b Wegner 2015, p. 70.

- ^ Dodson 2016, p. 57.

- ^ Wegner & Cahail 2015, see the abstract.

Sources

[edit]- Ayrton, Edward R.; Weigall, Arthur; Petrie, Flinders (1904). Abydos: Part III: 1904. Egypt exploration fund. Vol. 25. London. OCLC 474028932.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dodson, Aidan (2016). The Royal Tombs of Ancient Egypt. Barnsley Pen and Sword Archaeology. ISBN 978-1-47-382159-0.

- McCormack, Dawn (2006). "Borrowed Legacy, Royal Tombs S9 and S10 at South Abydos" (PDF). Expedition. 48 (2).

- "US diggers identify tomb of Pharoah [sic] Sobekhotep I". Times Live. January 6, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- Wegner, Josef W. (2015). "A royal necropolis at south Abydos: New Light on Egypt's Second Intermediate Period". Near Eastern Archaeology. 78 (2): 68–78. doi:10.5615/neareastarch.78.2.0068. S2CID 163519900.

- Wegner, J.; Cahail, K. (2015). "Royal Funerary Equipment of a King Sobekhotep at South Abydos: Evidence for the Tombs of Sobekhotep IV and Neferhotep I?". JARCE. 51: 123–164. doi:10.5913/jarce.51.2015.a006.