British Pakistanis

بَرِطانِیہ میں مُقِیم پاکِسْتانِی | |

|---|---|

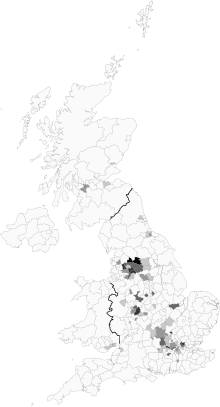

Distribution by local authority in the 2011 census. | |

| Total population | |

Northern Ireland: 1,596 – 0.08% (2021)[3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English (British and Pakistani) · Urdu · Punjabi[a] · Pahari-Pothwari · Pashto · Sindhi · Balochi · Brahui · Kashmiri · Khowar · Shina · Balti · others | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Islam (92.6%); minority follows other faiths (1.0%)[b] or are irreligious (1.2%) 2021 census, NI, England and Wales only[4][5] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Part of a series on |

| British people |

|---|

| United Kingdom |

| Eastern European |

| Northern European |

| Southern European |

| Western European |

| Central Asian |

| East Asian |

| South Asian |

| Southeast Asian |

| West Asian |

| African and Afro-Caribbean |

| Northern American |

| South American |

| Oceanian |

British Pakistanis (Urdu: بَرِطانِیہ میں مُقِیم پاکِسْتانِی; also known as Pakistani British people or Pakistani Britons) are Britons or residents of the United Kingdom whose ancestral roots lie in Pakistan. This includes people born in the UK who are of Pakistani descent, Pakistani-born people who have migrated to the UK and those of Pakistani origin from overseas who migrated to the UK.

The UK is home to the largest Pakistani community in Europe, with the population of British Pakistanis exceeding 1.6 million based on the 2021 Census. British Pakistanis are the second-largest ethnic minority population in the United Kingdom and also make up the second-largest sub-group of British Asians. In addition, they are one of the largest Overseas Pakistani communities, similar in number to the Pakistani diaspora in the UAE.[6][7]

Due to the historical relations between the two countries, immigration to the UK from the region, which is now Pakistan, began in small numbers in the mid-nineteenth century when parts of what is now Pakistan came under the British India. People from those regions served as soldiers in the British Indian Army and some were deployed to other parts of the British Empire. However, it was following the Second World War and the break-up of the British Empire and the independence of Pakistan that Pakistani immigration to the United Kingdom increased, especially during the 1950s and 1960s. This was made easier as Pakistan was a member of the Commonwealth.[8] Pakistani immigrants helped to solve labour shortages in the British steel, textile and engineering industries. The National Health Service (NHS) recruited doctors from Pakistan in the 1960s.[9]

The British Pakistani population has grown from about 10,000 in 1951 to over 1.6 million in 2021.[10][11] The vast majority of them live in England, with a sizable number in Scotland and smaller numbers in Wales and Northern Ireland. According to the 2021 Census, Pakistanis in England and Wales numbered 1,587,819 or 2.7% of the population.[12][13] In Northern Ireland, the equivalent figure was 1,596, representing less than 0.1% of the population.[3] The census in Scotland was delayed for a year and took place in 2022, the equivalent figure was 72,871, representing 1.3% of the population.[2] The majority of British Pakistanis are Muslim; around 93% of those living in England and Wales at the time of the 2021 Census stated their religion was Islam.[14]

Since their settlement, British Pakistanis have had diverse contributions and influences on British society, politics, culture, economy and sport. Whilst social issues include high relative poverty rates among the community according to the 2001 census,[15] progress has been made in other metrics in recent years, with the 2021 Census showing British Pakistanis as having amongst the highest levels of homeownership in England and Wales.[16][17]

History

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| British Pakistanis |

|---|

| History |

| Demographics |

| Languages |

|

| Culture |

| Religion |

| Notables |

| Related topics |

Pre-Independence

[edit]The earliest period of Asian migration to Britain has not been ascertained. It is known that Romani (Gypsy) groups such as the Romanichal and Kale arrived in the region during the Middle Ages, having originated from what is now North India and Pakistan and traveled westward to Europe via Southwest Asia around 1000 CE, intermingling with local populations over several centuries.[18][19][20]

Immigration from what is now Pakistan to the United Kingdom began long before Pakistan's independence in 1947. Muslim immigrants from Kashmir, Punjab, Sindh, the North-West Frontier and Balochistan and other parts of South Asia, arrived in the British Isles as early as the mid-seventeenth century as employees of the East India Company, typically as lashkars and sailors in British port cities.[21][22] These immigrants were often the first Asians to be seen in British port cities and were initially perceived as indolent due to their reliance on Christian charities.[23] Despite this, some of the early Pakistani immigrants married local white British women because there were few South Asian women in Britain.[24]

During the colonial era, Asians continued coming to Britain as seamen, traders, students, domestic workers, cricketers, political officials and visitors and some of them settled in the region.[25] South Asian seamen sometimes settled after ill- treatment or being abandoned by ship masters.[26][27]

Many early Pakistanis came to the UK as scholars and studied at major British institutions, before later returning to British India. An example of such a person is Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah came to the UK in 1892 and began an apprenticeship at Graham's Shipping and Trading Company. After completing his apprenticeship, Jinnah joined Lincoln's Inn, where he trained as a barrister. At 19, he became the youngest person from South Asia to be called to the bar in Britain.[28]

British interwar period

[edit]Most early Pakistani settlers (then part of the British India Empire) and their families moved from port towns to the Midlands, as Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, many expatriates mainly hailing from the city of Mirpur worked in munitions factories in Birmingham. After the war, most of these early settlers stayed on in the region and took advantage of an increase in the number of jobs.[29] These settlers were later joined by their families.[30]

In 1932, the Indian National Congress survey of 'all Indians outside India' (of which Pakistani regions were then a part) estimated that there were 7,128 Indians in the United Kingdom.[31]

There were 832,500 Muslim Indian soldiers in 1945; most of these recruits were from what is now Pakistan.[32] These soldiers fought alongside the British Army during the First and Second World Wars, particularly in the former during the Western Front and in the latter, during the Battle of France, the North African Campaign and the Burma Campaign. Many contributed to the war effort as skilled labourers, including as assembly-line workers in the aircraft factory at Castle Bromwich, Birmingham, which produced Spitfire fighter aircraft.[32] Most returned to South Asia after their service, although many of these former soldiers returned to Britain in the 1950s and 1960s to fill labour shortages.

Post-Independence

[edit]Following the Second World War, the break-up of the British Empire and the independence of Pakistan, Pakistani immigration to the United Kingdom increased, especially during the 1950s and 1960s. Many Pakistanis came to the UK following the turmoil during the partition of India and Pakistani independence. Among them were those who migrated to Pakistan upon displacement from India and then migrated to the UK; thus becoming secondary migrants.[33] Migration was made easier as Pakistan was a member of the Commonwealth of Nations.[8] Employers invited Pakistanis to fill labour shortages which arose in Britain after the Second World War.

As Commonwealth citizens, they were eligible for most British civic rights. They found employment in the textile industries of Lancashire and Yorkshire, manufacturing in the West Midlands and the car production and food processing industries of Luton and Slough. It was common for Pakistani employees to work on night shifts and other less desirable hours.[34]

Many expatriates began emigrating from Pakistan after the completion of the Mangla Dam in Mirpur, Azad Kashmir, in the late-1950s led to the destruction of hundreds of villages. Up to 5,000 people from Mirpur (5% of the displaced)[35] left for Britain, while others were allotted land in neighbouring Punjab or used monetary compensation to resettle elsewhere in Pakistan.[33] The British contractor which had built the dam gave the displaced community legal and financial assistance.[36] Those from unaffected areas of Pakistan, such as the Punjab, also emigrated to the UK to help fill labour shortages. Pakistanis began leaving Pakistan in the 1960s. They worked in the foundries of the English Midlands and a significant number also settled in Southall, West London.[37]

During the 1960s, a considerable number of Pakistanis also arrived from urban areas. Many of them were qualified teachers, doctors and engineers.[34] They had a predisposition to settle in London because of its greater employment opportunities compared to the Midlands or the North of England.[34] Most medical staff from Pakistan were recruited in the 1960s and almost all worked for the National Health Service.[38] At the same time, the number of Pakistanis coming over as workers declined.[33]

In addition, there was a stream of migrants from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).[30][39] During the 1970s, many East African Asians, most of whom already held British passports because they were brought to Africa by British colonialists, entered the UK from Kenya and Uganda. Idi Amin expelled all Ugandan Asians in 1972 because of his Black supremacist views and the perception that they were responsible for the country's economic stagnation.[40] The Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 and Immigration Act 1971 largely restricted any further primary immigration to the UK, although family members of already-settled immigrants were allowed to join their relatives.[41]

The early Pakistani workers who entered the UK came intending to work temporarily and eventually returning home. However, this changed into permanent family immigration after the 1962 Act, as well as socio-economic circumstances and the future of their children, which most families saw lay in Britain.[33]

When the UK experienced deindustrialisation in the 1970s, many British Pakistanis became unemployed. The change from the manufacturing sector to the service sector was difficult for ethnic minorities and working-class White Britons alike; especially for those with little academic education. The Midlands and North of England were areas which were heavily reliant on manufacturing industries and the effects of deindustrialisation continued to be felt in these areas.[42] As a result, increasing numbers of British Pakistanis resorted to self-employment. National statistics from 2004 showed that one in seven British Pakistani men work as taxi drivers or chauffeurs.[43] Whilst social issues include high relative poverty rates (55%) among the community according to the 2001 census,[15] progress has been made in recent years, however British Pakistanis alongside British Bangladeshis are still the most likely ethnicity groups to have the highest rates of poverty.[44] Despite relatively high levels of home ownership,[17] 48 per cent of Pakistani households were classified as in poverty after housing costs in the three-year period to 2022/23. The equivalent figure for child poverty in Pakistani households stood at 58 per cent.[44]

Demographics

[edit]| Region / Country | 2021[46] | 2011[50] | 2001[54] | 1991[57] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| 1,570,285 | 2.78% | 1,112,282 | 2.10% | 706,539 | 1.44% | 449,646 | 0.96% | |

| —West Midlands | 319,165 | 5.36% | 227,248 | 4.06% | 154,550 | 2.93% | 98,612 | 1.91% |

| —North West | 303,611 | 4.09% | 189,436 | 2.69% | 116,968 | 1.74% | 77,150 | 1.15% |

| —Yorkshire and the Humber | 296,437 | 5.41% | 225,892 | 4.28% | 146,330 | 2.95% | 94,820 | 1.96% |

| —Greater London | 290,549 | 3.30% | 223,797 | 2.74% | 142,749 | 1.99% | 87,816 | 1.31% |

| —South East | 145,311 | 1.57% | 99,246 | 1.15% | 58,520 | 0.73% | 35,946 | 0.48% |

| —East of England | 99,452 | 1.57% | 66,270 | 1.13% | 38,790 | 0.72% | 24,713 | 0.49% |

| —East Midlands | 71,038 | 1.46% | 48,940 | 1.08% | 27,829 | 0.67% | 17,407 | 0.44% |

| —North East | 27,290 | 1.03% | 19,831 | 0.76% | 14,074 | 0.56% | 9,257 | 0.36% |

| —South West | 17,432 | 0.31% | 11,622 | 0.22% | 6,729 | 0.14% | 3,925 | 0.09% |

| 72,871[α] | 1.34% | 49,381 | 0.93% | 31,793 | 0.63% | 21,192 | 0.42% | |

| 17,534 | 0.56% | 12,229 | 0.40% | 8,287 | 0.29% | 5,717 | 0.20% | |

| Northern Ireland | 1,596 | 0.08% | 1,091 | 0.06% | 668 | 0.04% | — | — |

| 1,662,286 | 2.48% | 1,174,602 | 1.86% | 747,285 | 1.27% | 476,555[β] | 0.87% | |

Population

[edit]

According to the 2021 Census, Pakistanis in England and Wales enumerated 1,587,819 or 2.7% of the population.[13][12] According to estimates by the Office for National Statistics, the number of people born in Pakistan living in the UK in 2021 was 456,000, which makes it the third most common country of birth in the UK.[59]

The ten local authorities with the largest proportion of people who identified as Pakistani were: Pendle (25.59%), Bradford (25.54%), Slough (21.65%), Luton (18.26%), Blackburn with Darwen (17.79%), Birmingham (17.04%), Redbridge (14.18%), Rochdale (13.64%), Oldham (13.55%) and Hyndburn (13.16%). In Scotland, the highest proportion was in East Renfrewshire at 5.25%; in Wales, the highest concentration was in Newport at 3.01%; and in Northern Ireland, the highest concentration was in Belfast at 0.14%.[60]

The Pakistan government's Ministry of Overseas Pakistanis estimates that 1.26 million Pakistanis eligible for dual nationality live in the UK, constituting well over half of the total number of Pakistanis in Europe.[11][61] Up to 250,000 Pakistanis come to the UK each year, for work, to visit or other purposes.[62] Likewise, up to 270,000 British citizens travel to Pakistan each year, mainly to visit family.[62][63] Excluding British citizens of Pakistani descent, the number of individuals living in the UK with a Pakistani passport was estimated at 188,000 in 2017, making Pakistan the eighth most common non-British nationality in the UK.[64]

The majority of British Pakistanis originate from the Azad Kashmir and Punjab regions, with a smaller number from other parts of Pakistan including Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Gilgit-Baltistan and Balochistan.[65][66][34][67]

The cities or districts with the largest communities, by Pakistani ethnicity in the England and Wales 2021 census, are as follows: Birmingham (pop. 195,102), Bradford (139,553), Manchester (65,875), Kirklees (54,795), Redbridge (44,000) and Luton (41,143).[68]

Historic

[edit]In the 2011 UK Census, 1,174,983 residents classified themselves as ethnically Pakistani (excluding people of mixed ethnicity), regardless of their birthplace; 1,112,212 of them lived in England.[10] This represented an increase of 427,000 over the 747,285 residents recorded in the 2001 UK Census.[69]

Demographer Ceri Peach has estimated the number of British Pakistanis in the 1951 to 1991 censuses. He back-projected the ethnic composition of the 2001 census to the estimated minority populations during previous census years. The results are as follows:

| Year | Population (rounded to nearest 1,000)[70] |

|---|---|

| 1951 (estimate) | 10,000 |

| 1961 (estimate) | 25,000 |

| 1971 (estimate) | 119,000 |

| 1981 (estimate) | 296,000 |

| 1991 (estimate) | 477,000 |

| 2001 (census) | 747,000 |

| 2011 (census) | 1,175,000[10] |

Population distribution

[edit]Birthplace/year of arrival of British Pakistanis in England and Wales (2021 census)[71]

At the time of the 2021 Census, the local authorities with the largest proportion of British Pakistanis were Pendle (25.59%), Bradford (25.54%), Slough (21.65%), Luton (18.26%) and Blackburn with Darwen (17.79%). The distribution of people describing their ethnicity as Pakistani in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland was as follows:[60][3][2]

| Region | Number of British Pakistanis | Percentage of total British Pakistani population | British Pakistanis as percentage of region's population | Significant Communities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | 1,570,285 | 2.80% | ||

| North East England | 27,290 | 1.00% | Newcastle-Upon-Tyne - 2.9%

Middlesbrough - 6.2% Stockton-On-Tees - 2.5% | |

| North West England | 303,611 | 4.10% | Manchester - 11.9%

Rochdale - 13.6% Oldham - 13.5% Blackburn With Darwen - 17.8% Pendle - 25.6% Burnley - 10.7% Bury - 7.8% Bolton - 9.4% Hyndburn - 13.2% | |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 296,437 | 5.40% | Bradford - 25.5%

Kirklees - 12.6% Calderdale - 8.5% Sheffield - 5.0% Leeds - 3.9% | |

| East Midlands | 71,038 | 1.50% | Derby - 8.0%

Nottingham - 6.7% Leicester - 3.4% Oadby and Wigston - 4.0% | |

| West Midlands | 319,165 | 5.40% | Birmingham - 17.0%

Walsall - 6.9% Stoke-On-Trent - 6.0% Dudley - 4.6% Sandwell - 6.5% East Staffordshire - 7.0% | |

| East of England | 99,452 | 1.60% | Luton - 18.3%

Peterborough - 7.9% Watford - 8.0% | |

| London | 290,459 | 3.30% | London Borough of Waltham Forest - 10.3%

London Borough of Newham - 8.9% London Borough of Redbridge - 14.2% | |

| South East England | 145,311 | 1.60% | Slough - 21.7%

Buckinghamshire - 5.3% Woking - 7.0% Crawley - 5.2% Reading - 4.8% Oxford - 4.1% Windsor and Maidenhead - 4.0% | |

| South West England | 17,432 | 0.30% | Bristol - 1.9% | |

| Scotland | 72,871 | 1.34% | Glasgow - 5.0%

Edinburgh - 1.5% East Renfrewshire - 5.3% North Lanarkshire - 1.5% | |

| Wales | 17,534 | 0.60% | Cardiff - 2.4%

Newport - 3.0% | |

| Northern Ireland | 1,596 | 0.08% | Belfast - 0.14% | |

| Total UK | 1,662,286 | 2.48% |

London

[edit]

Greater London has the largest Pakistani community in the United Kingdom. The 2021 Census recorded 290,549 Pakistanis living in London.[60] However, it only forms 3.3% of London's population, which is significantly lower than other British cities. The population is very diverse, with comparable numbers of Punjabis, Pashtuns and Muhajirs, and smaller communities of Sindhis and Balochs.[65][6] This mix makes the Pakistani community of London more diverse than other UK communities, whereas a high proportion of Pakistani communities in Northern England came from Azad Kashmir.[34]

The largest concentrations are in East London, especially in Redbridge, Waltham Forest, Newham and Barking and Dagenham. Significant communities can also be found in the boroughs of Ealing, Hounslow, and Hillingdon in West London and Merton, Wandsworth and Croydon in South London.[73]

Birmingham

[edit]Birmingham has the second-largest Pakistani community in the United Kingdom. The 2021 Census recorded that there were 195,102 Pakistanis living in Birmingham, making up 17% of the city's total population.[60]

The largest concentrations are in Sparkhill, Alum Rock, Small Heath and Sparkbrook.[74]

Bradford

[edit]

Bradford has the third-largest Pakistani community in the United Kingdom. The 2021 Census recorded 139,553 Pakistanis, making up 25.5% of the city's total population.[60]

The largest concentrations are in Manningham, Toller, Bradford Moor, Heaton, Little Horton and Keighley.[73]

Manchester

[edit]

Manchester has the fourth-largest Pakistani community in the United Kingdom. The 2021 Census recorded 65,875 Pakistanis, making up 11.9% of the city's total population.[60]

The largest concentrations are in Longsight, Cheetham Hill, Rusholme and Crumpsall.[73]

In the wider area of Greater Manchester, there were 209,061 Pakistanis, making up 7.3% of the population. The towns of Oldham and Rochdale have significant Pakistani populations, at 13.5% and 13.6% respectively.[60]

A significant number of Manchester-based Pakistani business families have moved down the A34 road to live in the affluent Heald Green area.[75] The late Professor Pnina Werbner associated the suburban movement of Pakistani-origin Muslims in Manchester with the formation of "gilded ghettoes" in the sought-after commuter suburbs of Cheshire.[37]

Luton

[edit]The 2021 Census recorded 41,143 Pakistanis in Luton, making up 18.3% of the total population.[60]

The largest concentrations are in Bury Park, Dallow and Challney.[73]

Glasgow

[edit]The 2022 Census recorded 30,912 Pakistanis in Glasgow, making up 4.98% of the city's total population.

There are large Pakistani communities throughout the city, notably in the Pollokshields area of South Glasgow, where there are said to be some 'high standard' Pakistani takeaways and Asian fabric shops.[76]

Pakistanis also make up the largest 'visible' ethnic minority in Scotland, representing nearly one-third of the non-White ethnic minority population.[77]

Languages

[edit]Most British Pakistanis speak English, and those who were born in the UK consider British English to be their first language. First-generation and recent immigrants speak Pakistani English. Urdu, the national language of Pakistan, is understood and spoken by many British Pakistanis at a native level, and is the fourth-most commonly spoken language in the UK.[78][79] Some secondary schools and colleges teach Urdu for GCSEs and A Levels.[80] Madrassas also offer it.[81][82] According to Sajid Mansoor Qaisrani, Urdu language periodicals of the 1990s published in UK used to focus exclusively on South Asian issues, with no relevance to British society.[83] Coverage of local British issues and problems of local Pakistanis in the UK used to be sparse.[83] Beyond Pakistani youth's interest in identifying with their ethnicity and religious identity, Urdu was of little use to them in finding suitable employment opportunities.[83]

The majority of Pakistanis in Britain are from Azad Kashmir and the neighbouring Pothohar Plateau in Northern Punjab who speak Pahari-Pothwari as their mother tongue. Due to this Pahari-Pothwari is the second most spoken mother tongue in the UK, even surpassing Welsh. [84]

As a large proportion of Pakistanis in Britain are from Punjab, Punjabi is commonly spoken amongst Pakistanis in Britain. Other Punjabi dialects are spoken in Britain, making Punjabi the third-most commonly spoken language.[78][85]

Other significant Pakistani languages spoken include Pashto, Saraiki, Sindhi, Balochi and a minority of others. These languages are not only spoken by British Pakistanis, but by other groups such as British Indians, British Afghans or British Iranians.[86]

Diaspora

[edit]Many British Pakistanis have emigrated from the UK, establishing a diaspora of their own. There are around 80,000 Britons in Pakistan,[87][88] a substantial number of whom are British Pakistanis who have resettled in Pakistan. The town of Mirpur in Azad Kashmir, where the majority of British Pakistanis hail from, has a large expatriate population of resettled British Pakistanis and is dubbed "Little England".[89][90][91]

Other British Pakistanis have migrated elsewhere to Europe, North America, Western Asia and Australia. Dubai, in the UAE, remains a popular destination for British Pakistani expatriates to live although there is no minimum wage and few anti-racism groups.[92]

Pakistanis in Hong Kong were given full British citizenship in 1997 during the handover of Hong Kong, when it ceased being a British colony to prevent them being made stateless.[93] Previously, as Hong Kong residents, they held the status of British Overseas Territories citizens.[94][95]

Religion

[edit]Over 90% of Pakistanis in the UK are Muslims. The largest proportion of these belong to the Sunni branch of Islam, mainly Deobandi (of the Tablighi Jamaat) and Sunni Barelvi, with a significant minority belonging to the Shia branch.[65]

Mosques, community centres and religious youth organisations play an integral part in British Pakistani social life.[96]

| Religion | England and Wales | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011[97] | 2021[98] | |||

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| 1,028,459 | 91.46% | 1,470,775 | 92.63% | |

| No religion | 12,041 | 1.07% | 18,533 | 1.17% |

| 17,118 | 1.52% | 12,327 | 0.78% | |

| 3,879 | 0.34% | 1,407 | 0.09% | |

| 3,283 | 0.29% | 590 | 0.04% | |

| 440 | 0.04% | 264 | 0.02% | |

| 700 | 0.06% | 230 | 0.01% | |

| Other religions | 588 | 0.05% | 1,005 | 0.06% |

| Not Stated | 58,003 | 5.16% | 82,691 | 5.21% |

| Total | 1,124,511 | 100% | 1,587,822 | 100% |

Culture

[edit]Pakistan's Independence Day is celebrated on 14 August in large Pakistani-populated areas of various cities. Pakistani Muslims also observe the month of Ramadan and mark the Islamic festivals of Eid al-Adha and Eid al-Fitr.[99]

The annual Birmingham Eid Mela attracts more than 20,000 British Pakistanis who celebrate the festival. The Eid Mela also welcomes Muslims of other ethnic backgrounds. International and UK Asian musicians help to celebrate the nationwide Muslim community through its culture, music, food and sport.[100]

Green Street in East London hosts Europe's "first Asian shopping mall".[101] A number of high-end Pakistani fashion and other retail brands have opened stores in the UK.[102][103]

Cuisine

[edit]

Pakistani and South Asian cuisines are highly popular in Britain and have nurtured a largely successful food industry. The cuisine of Pakistan is strongly related to North Indian cuisine, coupled with an exotic blend of Central Asian and Middle eastern cuisine flavours.[104]

The popular Balti dish has its roots in Birmingham, where it was believed to have been created by a Pakistani immigrant of Balti origin in 1977. The dish is thought to have borrowed native tastes from the northeastern Pakistani region of Baltistan.[105][106] In 2009, the Birmingham City Council attempted to trademark the Balti dish to give the curry Protected Geographical Status alongside items such as luxury cheese and champagne.[107] The area of Birmingham where the Balti dish was first served is known locally as the "Balti Triangle" or "Balti Belt".[108][109]

Chicken tikka masala has long been amongst the nation's favourite dishes and is claimed to have been invented by a Pakistani chef in Glasgow, though its origins remain disputed.[110][111] There has been support for a campaign in Glasgow to obtain European Union Protected Designation of origin status for it.[112]

Pakistanis are well represented in the British food industry. Many self-employed British Pakistanis own takeaways and restaurants. "Indian restaurants" in the North of England are almost entirely Pakistani owned.[113] According to the Food Standards Agency, the South Asian food industry in the UK is worth £3.2 billion, accounting for two-thirds of all eating out, and serving about 2.5 million British customers every week.[114] Curry sauces are sold in British supermarkets by British Pakistani entrepreneurs like Manchester-born Nighat Awan. Awan's Asian food business, Shere Khan, has made her one of the richest women in Britain.[115]

Successful fast-food chains founded by British Pakistanis include Chicken Cottage[116] and Dixy Chicken.[117]

Sports

[edit]The expansion of the British Empire led to cricket being played overseas.[118][119] Aftab Habib, Usman Afzaal, Kabir Ali, Owais Shah, Sajid Mahmood, Adil Rashid, Amjad Khan, Ajmal Shahzad, Moeen Ali, Zafar Ansari, Saqib Mahmood and Rehan Ahmed have played cricket for England.[120][121] Similarly, Asim Butt, Omer Hussain, Majid Haq, Qasim Sheikh and Moneeb Iqbal have represented Scotland. Prior to playing for England, Amjad Khan represented Denmark, the country of his birth. Imad Wasim became the first Welsh-born cricketer to represent Pakistan.[122][123] Former Pakistani cricketer Azhar Mahmood moved his career to England and became a naturalised British citizen.[124] There are several other British Pakistanis, as well as cricketers from Pakistan, who play English county cricket.[125][126]

Many young British Pakistanis find it difficult to make their way to the highest level of playing for England, despite much talent around the country. Many concerns about this have been documented although the number of British Pakistanis making progress in representing England is on the rise.[127]

The Pakistan national cricket team enjoys a substantial following among British Pakistanis, with the level of support translating to the equivalent of a home advantage whenever the team tours the UK. The "Stani Army" is a group consisting of British Pakistanis who follow the team, especially when they play in the UK. The Stani Army is seen as the "rival" fan club to India's "Bharat Army".[128][129][130][131][132] England and Pakistan share a long cricketing relationship, often characterised by rivalries.[133][134]

Football is also widely followed and played by many young British Pakistanis (see British Asians in association football). Many players on the Pakistan national football team are British-born Pakistanis who became eligible to represent the country because of their Pakistani heritage. Masood Fakhri was the first Pakistani football player to score a hat trick in an international game, and the first player from South Asia to play in England, where he played for Bradford City before retiring.[135] Zesh Rehman is a football defender who played briefly for Fulham F.C., becoming the first British Asian to play in the Premier League, before also playing for the English national U-18, U-19 and U-20 football teams until eventually opting for Pakistan.[136] Easah Suliman became the first player of Asian heritage to captain an England football side, having done so at Under-16, Under-17 and Under-19 levels,[137] until eventually opting for Pakistan at senior level.[138][139] Suliman played every game at centre back in the England Under-19s victorious UEFA European Under-19 Championship campaign in July 2017, scoring the opening goal in England's 2–1 final victory over Portugal.[140]

Zidane Iqbal signed his first professional contract with Manchester United in April 2021,[141][142] and made his first-team debut for Manchester United on 8 December 2021 as an 89th-minute substitute in a Champions League match against Young Boys.[143] Thus, he became the first British-born South Asian to play for the senior club, and the first ever British South Asian to play in the Champions League.[144][145]

Other notable British Pakistani footballers include Adnan Ahmed, Amjad Iqbal, Atif Bashir, Shabir Khan, Otis Khan, Adil Nabi, Rahis Nabi, Samir Nabi and Harun Hamid.

Hockey and polo are commonly played in Pakistan, with the former being a national sport, but these sports are not as popular among British Pakistanis, possibly because of the urban lifestyles which the majority of them embrace. Imran Sherwani was a hockey player of Pakistani descent who played for the English and Great Britain national field hockey teams.[146]

Adam Khan is a race car driver from Bridlington, Yorkshire. He represents Pakistan in the A1 Grand Prix series. Khan is currently the demonstration driver for the Renault F1 racing team.[147] Ikram Butt was the first South Asian to play international rugby for England in 1995.[148] He is the founder of the British Asian Rugby Association and the British Pakistani rugby league team, and has also captained Pakistan. Amir Khan is the most famous British Pakistani boxer. He is the current WBA World light welterweight champion and 2004 Summer Olympics silver medalist.[149] Matthew Syed was a table tennis international, and the English number one for many years.[150] Lianna Swan is a swimmer who has represented Pakistan in several events.[151]

Literature

[edit]A number of British Pakistani writers are notable in the field of literature. They include Tariq Ali, Kamila Shamsie, Nadeem Aslam, Mohsin Hamid and others.[152]

Through their publications, diaspora writers have developed a body of work that has come to be known as Pakistani English literature.[153]

Ethnicity and cultural assimilation

[edit]A report of a study conducted by The University of Essex found British Pakistanis identify with 'Britishness' more than any other Britons. The study is one of several recent studies that have found that Pakistanis in Britain express a strong sense of belonging in Britain. The report showed that 90% of Pakistanis feel a strong sense of belonging in Britain compared to 84% of white Britons.[154]

English Pakistanis tend to identify much more with the United Kingdom than with England, with 63% describing themselves in a Policy Exchange survey as exclusively "British" and not "English" in terms of nationality, and only 15% saying they were solely English.[155]

Azad Kashmiris

[edit]

Around 70% of all British Pakistanis trace their origins to the administrative territory of Azad Kashmir in northeastern Pakistan, mainly from the Mirpur, Kotli and Bhimber districts.[156][157]

Christopher Snedden writes that most of the native residents of Azad Kashmir are not of Kashmiri ethnicity; rather, they could be called "Jammuites" due to their historical and cultural links with that region, which is coterminous with neighbouring Punjab and Hazara.[158][159] Because their region was formerly a part of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir and is named after it, many Azad Kashmiris have adopted the "Kashmiri" identity, whereas in an ethnolinguistic context, the term "Kashmiri" would ordinarily refer to natives of the Kashmir Valley region.[160] The population of Azad Kashmir has strong historical, cultural and linguistic affinities with the neighbouring populations of upper Punjab and Potohar region of Pakistan.[161][162]

The first generation migrant from Azad Kashmir were not highly educated, and being from rural settlements, had little or no experience of urban living in Pakistan.[7] Migration from Jammu and Kashmir began soon after the Second World War as the majority of the male population of this area and the Potohar region worked in the British armed forces, as well as to fill labour shortages in industry. But the mass migration phenomenon accelerated in the 1960s, when, to improve the supply of water, the Mangla Dam project was built in the area, flooding the surrounding farmlands. Up to 50,000 people from Mirpur (5% of the displaced) resettled in Britain. More Azad Kashmiris joined their relatives in Britain after benefiting from government compensation and liberal migration policies. Large Azad Kashmiri communities can be found in Birmingham, Bradford, Manchester, Leeds, Luton and the surrounding towns.[163]

The Azad Kashmiri expatriate community has made notable progress in UK politics and a sizeable number of MPs, councillors, lord mayors and deputy mayors are representing the community in different constituencies.[164]

Punjabis

[edit]Punjabis make up the second-largest sub-group of British Pakistanis, estimated to make up to a third of all British Pakistanis.[165] With an equally large number from Indian Punjab, two-thirds of all British Asians are of Punjabi descent, and they are the largest Punjabi community outside of South Asia,[165] resulting in Punjabi being the third-most commonly spoken language in the UK.[78][85]

People who came from the Punjab area integrated much more easily into the British society as early Punjabi immigrants to Britain tended to have higher education credentials and found it easier to assimilate because many already had a basic knowledge of the English language (primarily Pakistani English).[37] Research by Teesside University has found the British Punjabi community of late has become one of the most highly educated and economically successful ethnic minorities in the UK.[166]

Most Pakistani Punjabis living in the UK trace their roots to villages of the Pothohar region (Jhelum, Gujar Khan, Attock ) of northern Punjab, along with villages in the Central Punjab (Faisalabad, Sahiwal, Gujrat, and Sargodha) region, while more recent immigrants have also arrived from large cities such as Lahore and Multan.[7][167] British Punjabis are commonly found in the south of England, the Midlands, and the major cities in the north (with smaller minorities in former mill towns in Lancashire and Yorkshire).[168]

Pashtuns

[edit]Pakistani Pashtuns in the United Kingdom mainly originate from the provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and northern Balochistan in Pakistan, though there are also smaller communities from other parts of Pakistan, such as Pashtuns of Punjab from Attock.[36] There are several estimates of the Pashtun population in the UK. Ethnologue estimates that there are up to 87,000 native Pashto-speakers in the UK; this figure also includes Afghan immigrants belonging to the Pashtun ethnicity.[169] Another report shows that there are over 100,000 Pashtuns in Britain, making them the largest Pashtun community in Europe.[170]

Major Pashtun settlement in the United Kingdom can be dated over the course of the past five decades. There is a British Pashtun Council which has been formed by the Pashtun community in the UK.

British Pashtuns have continued to maintain ties with Pakistan over the years, taking keen interest in political and socioeconomic developments in Pakistan.[170]

Sindhis

[edit]There are over 30,000 Sindhis in Britain.[171][86]

Baloch

[edit]There is a small Baloch community in the UK, originating from the Balochistan province of southwestern Pakistan and neighbouring regions.[172] There are many Baloch associations and groups active in the UK, including the Baloch Students and Youth Association (BSYA),[173][174] Baloch Cultural Society, Baloch Human Rights Council (UK) and others.[175]

Some Baloch political leaders and workers are based in the UK, where they found exile.[176][177][178][179]

Muhajirs

[edit]

There is also a significant albeit smaller community Muhajirs in the UK.[172] Muhajirs originally migrated from present-day India to Pakistan following the partition of British India in 1947. Most of them settled in Pakistan's largest city Karachi, where they form the demographic majority. Many Muhajir Pakistanis later migrated to Britain, effecting a secondary migration.[33]

Altaf Hussain, leader of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM)—the largest political party in Karachi, with its roots lying in the Muhajir community—has been based in England in self-imposed exile since 1992. He is controversially regarded to have virtually "ruled" and "remotely governed" Karachi from his residence in the north London suburb of Edgware.[180][181] Another notable includes the 2016 Mayor of London Sadiq Khan, who is of Muhajir origin.[182]

Others

[edit]There is also a Pakistani Hazara community in the UK, concentrated particularly in Milton Keynes, northeastern London, Southampton and Birmingham. They migrated to the UK from Quetta and its surroundings, which is historically home to the large Hazara population in Pakistan.[183][184][185]

Health and social issues

[edit]Health

[edit]Pakistanis together with Bangladeshis in the UK have poor health by many measures, for instance there is a fivefold rate of diabetes.[186] Pakistani men have the highest rate of heart disease in the UK.[187]

In the UK, women of South Asian heritage, including British Pakistanis, are the least likely to attend breast cancer screening. A study showed that British-Pakistani women faced cultural and language barriers and were not aware that breast screening takes place in a female-only environment.[188][189][190]

Sexual health

[edit]British Pakistanis, male and female, on average claim to have had only one sexual partner. The average British Pakistani male claims to have lost his virginity at the age of 20, the average female at 22, giving an average age of 21. 3.2% of Pakistani males report that they have been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection (STI), compared to 3.6% of Pakistani females.[191]

Cultural norms regarding issues such as chastity and marriage have resulted in British Pakistanis having a substantially older age for first intercourse, a lower number of partners, and lower STI rates than the national average.[191]

Cousin marriages and health risks

[edit]Research in Birmingham in the 1980s suggested that 50-70% of marriages within the Pakistani community were consanguineous (blood related).[192] In 2005, it was estimated that nationwide 55% of British Pakistanis were married to a first cousin[193] and around 70% in Bradford.[194][195] A more recent study on the Bradford Pakistani community in 2023 has suggested that there has been a sharp fall in the number of babies with parents who were first or second cousins, falling from 60% in 2013 to now only 46%. One teenager in the study noted "If you're really romantically into your cousin you can go for it, but now there isn't as much pushing of cousin marriage."[196]

Such a close relationship can double the likelihood of a child suffering from a birth defect from 3% to 6%.[197][198] Children born to closely related Pakistani parents had an autosomal recessive condition rate of 4% compared to 0.1% for European parents.[199][192]

Cousin marriages or marriages within the same tribe and clan are common in some parts of South Asia, including rural areas of Pakistan.[200] A major motivation is to preserve patrilineal tribal identity.[201] The tribes to which British Pakistanis belong include Jats, Ahirs, Gujjars, Awans, Arains, Rajputs and several others, all of whom are spread throughout Pakistan and north India. As a result, there are some common genealogical origins within these tribes.[202] Some British Pakistanis view cousin or in-tribe marriages as a way of preserving this ancient tribal tradition and maintaining a sense of brotherhood, an extension of the biradri (brotherhood) system which underpins community support networks.[172][203]

Most British Pakistanis prefer to marry within their own ethnic group.[204] In 2009, it was estimated that six in ten British Pakistanis chose a spouse from Pakistan.[62]

Forced marriage

[edit]According to the British Home Office, cases involving Pakistan are routinely the most common country in which cases of forced marriage are investigated. In 2014, 38% of the cases of forced marriage investigated involved families of Pakistani origin.[205] This figure rose to 49% in 2022, around three-quarters of victims were females and just over half of cases involved persons under 21.[206]

60% of the Pakistani forced marriages handled by the British High Commission assistance unit in Islamabad are linked to the small towns of Bhimber and Kotli and the region of Mirpur in Azad Kashmir.[207]

According to 2017 data by the Forced Marriage Unit (FMU), a joint effort between the Home Office and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, of the 439 callers related to Pakistan, 78.8% were female and 21.0% were male, 13.7% were under the age of 15 and another 13.0% were aged 16–17. Over 85% of the cases dealt with by the FMU were dealt with entirely in the UK, preventing the marriage before it could take place. Victims were in some cases forced to sponsor a visa for the spouse.[208]

Education

[edit]Data from the 2021 Census shows that 33% of British Pakistanis in England and Wales hold degree level qualifications, compared to 31% of White British people. This has increased since 1991, when the figures for both groups holding a degree were 7% and 13%, respectively.[209][210][211]

25% of British Pakistanis in England and Wales did not have qualifications, compared to 18% of White British people, making them of one of the least qualified major groups.[210][212][211]

Secondary education

[edit]According to Department for Education statistics for the 2021–22 academic year, British Pakistani pupils in England attained below the national average for academic performance at A-Level, but above the national average for GCSE level. 15.8% of British Pakistani pupils achieved at least 3 As at A Level[213] and an average score of 49.1 was achieved in Attainment 8 scoring at GCSE level. In 2021, 31.5% of Pakistani students in England who were eligible for free school meals achieved a strong pass in English and Maths. This figure is 9% higher than the national average of 22.5%.[214]

In 2023, a British Pakistani girl achieved a record 34 GCSE qualifications. In addition, her IQ was registered at 161, which put her ahead of Albert Einstein[215]

Several Muslim schools also cater to British Pakistani pupils.[216][217]

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Higher education

[edit]There are 71,000 UK-domiciled British Pakistani students in the 2021-22 academic year, this represents 4.2% of all UK-domiciled students.[220] In 2017, approximately 16,480 British Pakistani students were admitted to university, almost a two-fold increase from 8,460 in 2006.[221]

In 2021, 58.4% of British Pakistanis chose to continue their studies at the university level. This was a higher rate than average nationally (44%), and higher than the rate for White British (39%).[222]

Science and mathematics are the most popular subjects at A-Level and degree level among the youngest generation of British Pakistanis, as they begin to establish themselves within the field.[223]

In addition, there are over 10,000 Pakistani international students who enrol and study at British universities and educational institutions each year.[62][224] There are numerous student and cultural associations formed by Pakistani pupils studying at British universities.

Language education

[edit]Urdu courses are available in the UK and can be studied at GCSE and A-Level.[80][225] Urdu degrees are offered by several British universities and institutes, while several others are also hoping to offer courses in Urdu, open to established speakers as well as beginners, in the future.[226][227][228][229]

The Punjabi language is also offered at GCSE and A-Level,[230] and taught as a course by two universities: SOAS, University of London (SOAS)[231] and King's College London.[232] Pashto is presently taught at SOAS and King's College London as well.[233]

Economics

[edit]

Location has had a great impact on the success of British Pakistanis. The existence of a North-South divide leaves those in the north of England economically depressed, although there is a small concentration of more highly educated Pakistanis living in the suburbs of Greater Manchester and London, as some Pakistani immigrants have taken advantage of the trading opportunities and entrepreneurial environment which exist in major UK cities.[237] Material deprivation and under-performing schools of the inner city have impeded social mobility for many Azad Kashmiris.[237]

British Pakistanis based in large cities have found making the transition into the professional middle class easier than those based in peripheral towns. This is because cities like London, Manchester, Leeds, Liverpool, Newcastle, Glasgow and Oxford have provided a more economically encouraging environment than the small towns in Lancashire and Yorkshire.[37]

On the other hand, the decline in the British textile boom brought about economic disparities for Pakistanis who worked and settled in the smaller mill towns following the 1960s, with properties failing to appreciate enough and incomes having shrunk.[204]

Most of the initial funds for entrepreneurial activities were historically collected by workers in food processing and clothing factories.[238] The funds were often given a boost by wives saving "pin money" and interest-free loans exchanged between fellow migrants. By the 1980s, British Pakistanis began dominating the ethnic and halal food businesses, Indian restaurants, Asian fabric shops, and travel agencies.[237] Other Pakistanis secured ownership of textile manufacturing or wholesale businesses and took advantage of cheap family labour. The once multimillion-pound company Joe Bloggs is an example.

Clothing imports from Southeast Asia began to affect the financial success of these mill-owning Pakistanis in the 1990s. However, some Pakistani families based in the major cities managed to buck this trend by selling or renting out units in their former factories.[237]

Economic status

[edit]Statistics from the 2011 census show that Pakistani communities in England, particularly in the North and the Midlands, are disproportionately affected by low pay, unemployment and poverty.[239][240] 32% cent of British Pakistanis live in a deprived neighbourhood, compared to 10% for England overall.[241] Consequently, many fall within the welfare net.[242] In Scotland, however, Pakistanis were less likely to live in a deprived area than the average.[243] Sir Anwar Pervez, owner of one of the UK's largest companies, the Bestway group,[244] and his family have assets of £1.364 billion, placing them 125th on the Sunday Times Rich List 2021.[245]

In addition, several wealthy Pakistanis, including prominent politicians, own millions of pounds' worth of assets and properties in the UK, such as holiday homes.[246][247][248][249] In 2017, 19.8% of Pakistani secondary school students were eligible for free school meals, compared to 13.1% of White British pupils. Amongst pupils in Key Stage 1, 14.1% of both Pakistani and White British children were eligible for free school meals.[250]

Research from the Resolution Foundation published in 2020 has found that British Pakistanis hold the third highest median total household net wealth among major British ethnic groups at £232,200.[251]

| Ethnic group | Median total household net wealth (2016–18) |

|---|---|

| Indian | £347,400 |

| White British | £324,100 |

| Pakistani | £232,200 |

| Black Caribbean | £125,400 |

| Bangladeshi | £124,700 |

| Other White | £122,800 |

| Chinese | £73,500 |

| Black African | £28,400 |

Employment

[edit]

Since 2004, the combined Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities have consistently had the lowest rate of employment out of all ethnic groups, although this figure has improved from 44% in 2004 to 61% in 2022. This is in comparison to the nationwide figures of 73% in 2004 and 76% in 2022.[252] In 2022, the combined group were also the most likely ethnic group to be economically inactive with 33% of 16 to 64-year-olds out of work and not looking for employment, rising to 48% for Pakistani and Bangladeshi women compared to 24% of White British women.[253] According to figures in the same year for 16-64 year olds, the combined group also had the lowest employment figure at 61% and the largest employment discrepancy by gender at 75% for men and 46% for women.[254] The average hourly pay for the combined group in the same year was the lowest out of all ethnicity groups at £12.03.[255] In 2019, before the two ethnicities were combined, Pakistanis had the lowest pay out of all ethnicities with a slightly lower median hourly pay than Bangladeshis at £10.55 compared to £10.58.[256] In the 2017 to 2020 period, 47% of the community lived in households classified as low income (after housing costs), the second highest proportion after Bangladeshis, compared to 22% of all households in the UK.[257]

The Economist has argued that the lack of a second income in households was "the main reason" why many Bangladeshi and Pakistani families live below the poverty line and the resulting high proportion reliant on welfare payments from the government.[258]

According to the 2011 Census:[259]

| Economic Activity | All | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employed | 49% | 68% | 32% |

| Self-Employed | 24% | 30% | 10% |

| Economically Inactive | 41% | 24% | 60% |

Data from the 2011 Census shows British Pakistanis had one of the lowest employment rates amongst other ethnic groups and a lower than average employment rate in all regions of England and Wales, reported at 49%. The statistics also showed Pakistanis had one of the highest rates of unemployment at 12%.

Around 60% of British Pakistani women were economically inactive and 15% were unemployed in 2011.[259] Amongst older employed Pakistani women, many work as packers, bottlers, canners, fillers, or sewing machinists.[43] In 2012, Pakistani women began to surge into the labour market, although this was noted as many merely moving from economic inactivity to unemployment.[258]

Office for National Statistics figures for 2020 show British Pakistanis are far more likely to be self-employed than any other ethnic group, at 25%.[260] Traditionally, many British Pakistanis have been self-employed, with many working in the transport industry or family-run businesses in the retail sector.[6]

In the fourth quarter of 2019, the Labour Force Survey showed that the employment rate for British Pakistanis stood at 57% and unemployment rates were 7%.[261]

According to General Medical Council statistics,[when?] 14,213 doctors from Pakistan are registered in the UK,[262] and 2,100 dentists of Pakistani ethnicity were registered with the General Dental Council as of 2017.[263] Pakistani-origin doctors make up 5.7% of all doctors in the UK[264] and Pakistan is one of the largest source countries of foreign young doctors in the UK.[265]

Housing

[edit]In the housing rental market, Pakistani landlords first rented out rooms to incoming migrants, who were mostly Pakistani themselves. As these renters settled in Britain and prospered to the point where they could afford to buy their own homes, non-Asian university students became these landlords' main potential customers. By 2000, several British Pakistanis had established low-cost rental properties throughout England.[237]

British Pakistanis are most likely to live in owner-occupied Victorian terraced houses of the inner city.[266] In the increasing suburban movement amongst Pakistanis living in Britain,[267] this trend is most conspicuous among children of Pakistani immigrants.[268] Pakistanis tend to place a strong emphasis on owning their own home and have one of the highest rates of home ownership in the UK at 73% in 2003-04, slightly higher than that of the White British population.[269] The 2021 census for England and Wales recorded a slight decline of ownership with 60% of Pakistanis either owning their home with a mortgage (37%) or outright (23%). 26% rent privately or live rent free and the remaining 14% rent from social housing.[17]

Many first generation British Pakistanis have invested in second homes or holiday homes in Pakistan.[270] They have purchased houses next to their villages and sometimes even in more expensive cities, such as Islamabad and Lahore. Upon reaching the retirement age, a small number hand over their houses in Britain to their offspring and settle in their second homes in Pakistan.[237] This relocation multiplies the value of their British state pensions. Investing savings in Pakistan has limited the funding available for investing in their UK businesses. In comparison, other migrant groups, like South Asian migrants from East Africa, have benefited from investing only in Britain.[237]

Social class

[edit]The majority of British Pakistanis are considered to be working or middle class.[271] According to the 2011 Census, 16.5% of Pakistanis living in England and Wales were in managerial or professional occupations, 19.3% in intermediate occupations, and 23.5% in routine or manual occupations. The remaining 24.4% and 16.3% were classified under never worked or long-term unemployed and full-time students.[272]

Whilst British Pakistanis living in the Midlands and the North are more likely to be unemployed or suffer from social exclusion,[34] some Pakistani communities in London and the south-east are said to be "fairly prosperous".[66] It was estimated that, in 2001, around 45% of British Pakistanis living in both inner and outer London were middle class.[273]

Media

[edit]Cinema

[edit]Notable films that depict the lives of British Pakistanis include My Beautiful Laundrette, which received a BAFTA award nomination, and the popular East is East which won a BAFTA award, a British Independent Film Award and a London Film Critics' Circle Award. The Infidel looked at a British Pakistani family living in East London,[274] and depicted religious issues and the identity crisis facing a young member of the family. The film Four Lions looked at issues of religion and extremism. It followed British Pakistanis living in Sheffield in the North of England. The sequel to East is East, called West is West, was released in the UK on 25 February 2011.[275]

Citizen Khan is a sitcom developed by Adil Ray which is based on a British Pakistani family in Sparkhill, Birmingham, dubbed the "capital of British Pakistan".[276] The soap opera EastEnders also features many British Pakistani characters.[277] Pakistani Lollywood films have been screened in British cinemas.[278][279] Indian Bollywood films are also shown in British cinemas and are popular with many second generation British Pakistanis and British Asians.[280]

Television

[edit]BBC has news services in Urdu and Pashto.[281][282] In 2005, the BBC showed an evening of programmes under the title Pakistani, Actually, offering an insight into the lives of Pakistanis living in Britain and some of the issues faced by the community.[283][284] The executive producer of the series said, "These documentaries provide just a snapshot of contemporary life among British Pakistanis—a community who are often misunderstood, neglected or stereotyped."[283]

The Pakistani channels of GEO TV, ARY Digital and many others are available to watch on subscription. These channels are based in Pakistan and cater to the Pakistani diaspora, as well as anyone of South Asian origin. They feature news, sports and entertainment, with some channels broadcast in Urdu/Hindi.

Mishal Husain is of Pakistani descent, and a newsreader and presenter for the BBC.[285] Saira Khan hosts the BBC children's programme Beat the Boss. Martin Bashir is a Christian Pakistani[286] who worked for ITV, then American Broadcasting Company, before becoming BBC News Religious Affairs correspondent in 2016.

Radio

[edit]The BBC Asian Network is a radio station available across the entire UK and is aimed at Britons of South Asian origin under 35 years of age.[287] Apart from this popular station, there are many other national radio stations for or run by the British Pakistani community, including Sunrise and Kismat Radio of London.

Regional British Pakistani stations include Asian Sound of Manchester, Radio XL and Apni Awaz of Bradford and Sunrise Radio Yorkshire which based in Bradford.[288] These radio stations generally run programmes in a variety of South Asian languages.

The Pakistani newspaper the Daily Jang has the largest circulation of any daily Urdu-language newspaper in the world.[289] It is sold at several Pakistani newsagents and grocery stores across the UK. Urdu newspapers, books and other periodical publications are available in libraries which have a dedicated Asian languages service.[290] Examples of British-based newspapers written in English include the Asian News (published by Trinity Mirror) and the Eastern Eye. These are free weekly newspapers aimed at all British Asians.[291][292]

British Pakistanis involved in print media include Sarfraz Manzoor, who is a regular columnist for The Guardian,[293] one of the largest and most popular newspaper groups in the UK. Anila Baig is a feature writer at The Sun, the biggest-selling newspaper in the UK.[294]

Politics

[edit]| British Pakistani MPs by election 1997-2019 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Labour | Conservative | Scottish National Party |

Other | Total | % of Parliament |

| 1997[295] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.15 |

| 2001[296] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.31 |

| 2005[297] | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.62 |

| 2010[298] | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1.08 |

| 2015[299] | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 1.54 |

| 2017[300] | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1.85 |

| 2019[301] | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 2.31 |

British Pakistanis are represented in politics at all levels. In 2019 there were fifteen British Pakistani MPs in the House of Commons.[303] Notable members have included Shadow Secretary of State for Justice Sadiq Khan[304] and Home Secretary, Sajid Javid,[305] described by The Guardian as a 'rising star' in the Tory party.[306] The Guardian stated that, "The treasury minister is highly regarded on the right and would be the Tories' first Muslim leader", whereas The Independent said he could become the next Chancellor of the Exchequer,[307] which he did in July 2019.[308] The 2019 United Kingdom general election saw a record number of British Pakistani candidates.[309]

Notable British Pakistanis in the House of Lords includes Minister for Faith and Communities and former chairman of the Conservative Party Sayeeda Warsi,[310] Tariq Ahmad, Nazir Ahmed,[311][312] and Qurban Hussain.[313] Mohammad Sarwar of the Labour Party was the first Muslim member of the British parliament, being elected in Glasgow in 1997 and serving until 2010.[314] In 2013, Sarwar quit British politics and returned to Pakistan, where he joined the government and briefly served as the Governor of Punjab.[315] Other politicians in Pakistan known to have held dual British citizenship include Rehman Malik,[316] Ishrat-ul-Ibad Khan,[317] and some members of the Pakistani national and provincial legislative assemblies.[318][319]

In 2007, 257 British Pakistanis were serving as elected councillors or mayors in Britain.[320] British Pakistanis make up a sizeable proportion of British voters and are known to make a difference in elections, both local and national.[321] They are much more active in the voting process, with 67% voting in the last general elections of 2005, compared to just over 60% for the country.[322]

Apart from their involvement in domestic politics, the British Pakistani community also maintains keen focus on the politics of Pakistan and has served as an important soft power prerogative in historical, cultural, economic and bilateral relations between Pakistan and the United Kingdom.[323][324] Major Pakistani political parties such as the Pakistan Muslim League (N),[325] Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf,[326] the Pakistan Peoples Party,[327] the Muttahida Qaumi Movement[328] and others have political chapters and support in the UK.

Some of the most influential names in Pakistani politics are known to have studied, lived or exiled in the UK.[329] London, in particular, has long served as a hub of Pakistani political activities overseas.[329][330][331][332] The British Azad Kashmiri community has a strong culture of diaspora politics, playing a significant role in advocating the settlement of the Kashmir conflict and raising awareness of human rights abuses in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir.[333][334][335] Much of Pakistani lobbying and intelligence operations in the UK are focused on this key diaspora issue.[336]

Labour Party

[edit]The Labour Party has traditionally been the natural choice for many British Pakistanis. The Labour Party are said to be more dependent on votes from British Pakistanis than the Conservative Party.[337] British Pakistani support for Labour reportedly fell because of party's decision to take part in the Iraq War,[338] when a substantial minority of Muslim voters switched from Labour to the Liberal Democrats.[339] A 2005 poll carried out by ICM Research (ICM) showed that 40% of British Pakistanis intended to vote for Labour in 2010, compared to 5% for the Conservative Party and 21% for the Liberal Democrats.[340] However, according to survey research, 60% of Pakistani voters voted Labour in the subsequent general election, held in 2010[341] and this figure rose to more than 90% in the 2017 general election.[339]

High-profile British Pakistani politicians within the Labour Party include Shahid Malik and Lord Nazir Ahmed, who became the first Muslim life peer in 1998.[342] Sadiq Khan became the first Muslim cabinet minister in June 2009, after being invited to accept the post by then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown.[343] Anas Sarwar served as an MP for Glasgow Central between 2010 and 2015, and was elected as leader of the Scottish Labour Party in February 2021.[344] Shabana Mahmood is the current Labour Chief Secretary to the Treasury.

Conservative Party

[edit]

Some commentators have argued the Conservative Party has become increasingly popular with some British Pakistanis, as they become more affluent.[346] However, analysis of a representative sample of ethnic Pakistani voters in the 2010 general election from the Ethnic Minority British Election Study shows that 13% of them voted Conservative, compared to 60% Labour and 25% Liberal Democrat.[341]

The proportion of British Pakistanis voting Conservative fell in the 2015 and 2017 general elections.[339] Michael Wade, chairman of the Conservative Friends of Pakistan, has argued that while polls have shown that only one third of British Pakistani men would never vote Conservative, "the fact is that the Conservative Party has not been successful in reaching out to the British Pakistani community; and so they, in turn, have not looked to the Conservative Party as the one that represents their interests".[347]

The Conservative Friends of Pakistan aims to develop and promote the relationship between the Conservative Party, the British Pakistani community and Pakistan.[348] David Cameron opened a new gym aimed at British Pakistanis in Bolton after being invited by Amir Khan in 2009.[349] Cameron also appointed Tariq Ahmad, Baron Ahmad of Wimbledon, a Mirpuri-born politician, a life peerage. Multi-millionaire Sir Anwar Pervez, who claims to have been born Conservative,[350] has donated large sums to the party.[351][352] Sir Anwar's donations have entitled him to become a member of the influential Conservative Leader's Group.[353]

Shortly after becoming the Conservative Party leader, Cameron spent two days living with a British Pakistani family in Birmingham.[354] He said the experience taught him about the challenges of cohesion and integration.[354]

Sajjad Karim was a member of the European Parliament before Brexit. He represented North West England through the Conservative Party. In 2005, Karim became the founding chairman of the European Parliament Friends of Pakistan Group. He is also a member of the Friends of India and Friends of Bangladesh groups.[355] Rehman Chishti became the new Conservative Party MP for Gillingham and Rainham in 2010.[356] Sayeeda Warsi was promoted to chairman of the Conservative Party by the prime minister shortly after the 2010 UK general election. Warsi was the shadow minister for community cohesion when the Conservatives were in opposition before the 2010 election. She was the first Muslim and first Asian woman to serve in a British cabinet. Both of Warsi's grandfathers served with the British Army in the Second World War.[357]

Liberal Democrats, Scottish National Party and Others

[edit]

In the 2003 Scottish Parliament elections, Scottish Pakistani voters supported the Scottish National Party (SNP) more than the average Scottish voter.[358] The SNP is a centre-left civil nationalist party that campaigns for the independence of Scotland from the United Kingdom. SNP candidate Bashir Ahmad was elected to the Scottish Parliament to represent Glasgow at the 2007 election, becoming the first member of the Scottish Parliament to be elected with a Scottish Asian background.[359] On 29 March 2023, Humza Yousaf was elected First Minister of Scotland, becoming first British Pakistani to held this position. He has also been serving as leader of Scottish National Party.

Salma Yaqoob is the former leader of the left-wing, anti-Zionist Respect Party. The small party has seen success in areas such as Sparkbrook in Birmingham and Newham in London, where there are large Pakistani populations. Qassim Afzal is a senior Liberal Democrat politician of Pakistani origin. In 2009 he accompanied the then Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom to meetings with Pakistan's president, Asif Ali Zardari.[360] There has never been a Pakistani MP in the Liberal Democrats.

Contemporary issues

[edit]Racism and discrimination

[edit]The chance of a Pakistani being racially attacked in a year is greater than 4%—the highest rate in the country, along with British Bangladeshis—though this has come down from 8% a year in 1996.[361]

Police recorded figures also showed that in 2018–19, the highest proportion of victims (18%) of racially aggravated hate crimes were of Pakistani ethnicity.[362] Between 2005 and 2012, just over half of the victims of Islamophobic incidents in London were Pakistani in ethnic appearance.[363]

The term "Paki" is often used as a racist slur to describe Pakistanis and can also be directed towards other non-Pakistani South Asians. There have been some attempts by the youngest generation of British Pakistanis to reclaim the word and use it in a non-offensive way to refer to themselves, though this remains controversial.[364]

In 2001, riots occurred in Bradford. Two reasons given for the riots were social deprivation and the actions of extreme right wing groups such as the National Front (NF).[365] The Anti-Nazi League held a counter protest to a proposed march by the NF leading to clashes between police and the local South Asian population, with the majority of those being involved being of Pakistani descent.[366][367]

"Paki-bashing"

[edit]Starting in the late 1960s,[368] and peaking in the 1970s and 1980s, violent gangs opposed to immigration took part in frequent attacks known as "Paki-bashing", which targeted and assaulted Pakistanis and other South Asians.[369] "Paki-bashing" was unleashed after Enoch Powell's inflammatory Rivers of Blood speech in 1968,[368] and peaked during the 1970s–1980s, with the attacks mainly linked to far-right fascist, racist and anti-immigrant movements, including the white power skinheads, the National Front, and the British National Party (BNP).[370][371]

These attacks were usually referred to as either "Paki-bashing" or "skinhead terror", with the attackers usually called "Paki-bashers" or "skinheads".[368] According to Robert Lambert, "influential sections of the national and local media" did "much to exacerbate" anti-immigrant and anti-Pakistani rhetoric.[371] The attacks were also fuelled by systemic failures of state authorities, which included under-reporting of racist attacks, the criminal justice system not taking racist attacks seriously, and racial harassment by police.[368]

Perception by the majority population

[edit]As per a 2013 YouGov research, British Pakistanis are seen to not integrate into society as well when compared to immigrants of African or Eastern European background but conversely they're also perceived to be "as hard-working as well as more entrepreneurial and less likely to be either leaning on the state or a drain on the economy than the other groups", and also "as less threatening in general and less corrupt than Eastern Europeans."[372]

Notable people

[edit]See also

[edit]Related Pakistanis

[edit]Related groups

[edit]Arts and entertainment

[edit]Other

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Scotland held its census a year later after the rest of the United Kingdom due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, data shown is for 2022 as opposed to 2021.

- ^ Figures are for Great Britain only, i.e. excludes Northern Ireland

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Ethnic group, England and Wales: Census 2021". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Scotland's Census 2022 - Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion - Chart data". Scotland's Census. National Records of Scotland. 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024. Alternative URL 'Search data by location' > 'All of Scotland' > 'Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion' > 'Ethnic Group'

- ^ a b c d "MS-B01: Ethnic group". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. 22 September 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ United Kingdom census (2021). "DT-0036 - Ethnic group by religion". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ "RM031 Ethnic group by religion". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ a b c "Britain's Pakistani community". The Daily Telegraph. 28 November 2008. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ a b c Werbner, Pnina (2005). "Pakistani migration and diaspora religious politics in a global age". In Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (eds.). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures around the World. New York: Springer. pp. 475–484. ISBN 0-306-48321-1.

- ^ a b Satter, Raphael G. (13 May 2008). "Pakistan rejoins Commonwealth – World Politics, World". The Independent. London. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ Butler, Patrick (18 June 2008). "How migrants helped make the NHS". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ a b c "2011 Census: Ethnic group, local authorities in the United Kingdom". Office for National Statistics. 11 October 2013. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ a b Nadia Mushtaq Abbasi. "The Pakistani Diaspora in Europe and Its Impact on Democracy Building in Pakistan" (PDF). International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Ethnic group - Census Maps, ONS". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Ethnic group, England and Wales - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Ethnic group by religion - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ a b Guy Palmer; Peter Kenway (29 April 2007). "Poverty rates among ethnic groups in Great Britain". Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ "Tenure by ethnic group - Household Reference Persons - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "The impacts of the housing crisis on people of different ethnicities". Trust for London. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Nelson, Dean (3 December 2012). "European Roma descended from Indian 'untouchables', genetic study shows". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

Later, they left to flee the fall of Hindu kingdoms in what is today Pakistan, with many setting off from near Gilgit.

- ^ Kelly, Nataly (2012). Found in Translation: How Language Shapes Our Lives and Transforms the World. Penguin Books. p. 48. ISBN 9781101611920.

Their roots date back to northern India and Pakistan in around 1000 CE. Invading forces pushed them from their homeland, starting a forced migration to today's Anatolia in western Turkey.

- ^ Reed, Judy Hale (2013). Indonesian Journal of International & Comparative Law (January 2014): Socio-Political Perspectives. Institute for Migrant Rights Press. p. 179.

Roma people originated from present-day India or Pakistan and migrated over a thousand years ago to Europe and other regions of the world.

- ^ "The First Asians in Britain". Fathom. Archived from the original on 11 April 2004. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ "History of Islam in the UK". BBC - Religions. 7 September 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ Fathom archive. "British Attitudes towards the Immigrant Community". Columbia University. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ Fisher, Michael Herbert (2006). Counterflows to Colonialism: Indian Traveller and Settler in Britain 1600–1857. Orient Blackswan. pp. 111–9, 129–30, 140, 154–6, 160–8, 172. ISBN 81-7824-154-4.

- ^ Parekh, Bhikhu (9 September 1997). "South Asians in Britain". History Today. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "The Goan community of London - Port communities - Port Cities". portcities.org.uk. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ "Find your ancestors in England & Wales Merchant Navy Crew Lists 1861-1913". Find My Past. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ D. N. Panigrahi, India's Partition: The Story of Imperialism in Retreat, 2004; Routledge, p. 16

- ^ Marco Giannangeli (10 October 2005). "Links to Britain forged by war and Partition". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ a b Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (2005). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities, Volume 1. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780306483219.

- ^ Visram, Rozina (30 July 2015). Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700-1947. Routledge. ISBN 9781317415336.

- ^ a b Sophie Hares (3 July 2009). ""Untold" story of WW2 stirs Muslim youth pride". Reuters. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "The Pakistani Community". BBC. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Robin Richardson; Angela Wood. "The Achievement of British Pakistani Learners" (PDF). Trentham Books. pp. 2, 1–17.

- ^ "Muslims in Britain: Past And Present". Islamfortoday.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ a b Kinship and continuity: Pakistani families in Britain. Routledge. 2000. pp. 26–32. ISBN 978-90-5823-076-8. Retrieved 27 April 2010.