L.H.O.O.Q.

L.H.O.O.Q. (French pronunciation: [ɛl aʃ o o ky]) is a work of art by Marcel Duchamp. First conceived in 1919, the work is one of what Duchamp referred to as readymades, or more specifically a rectified ready-made.[2] The readymade involves taking mundane, often utilitarian objects not generally considered to be art and transforming them, by adding to them, changing them, or (as in the case of his most famous work Fountain) simply renaming and reorienting them and placing them in an appropriate setting.[3] In L.H.O.O.Q. the found object (objet trouvé) is a cheap postcard reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci's early 16th-century painting Mona Lisa onto which Duchamp drew a moustache and beard in pencil and appended the title.[4]

Overview

[edit]

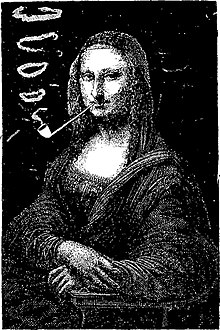

The subject of the Mona Lisa treated satirically had already been explored in 1887 by Eugène Bataille (aka Sapeck) when he created Mona Lisa smoking a pipe, published in Le Rire.[5] It is not clear if Duchamp was familiar with Bataille's interpretation.

The name of the piece, L.H.O.O.Q., is a gramogram; the letters pronounced in French sound like "Elle a chaud au cul", "She is hot in the arse",[6] or "She has a hot ass";[7] "avoir chaud au cul" is a vulgar expression implying that a woman has sexual restlessness. In a late interview (Schwarz 203), Duchamp gives a loose translation of L.H.O.O.Q. as "there is fire down below".

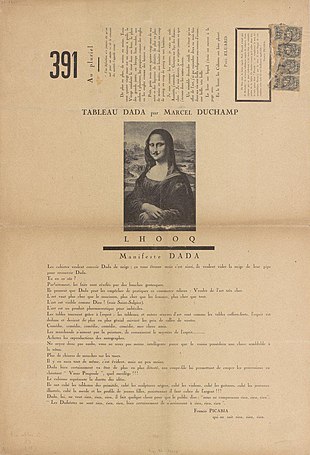

Francis Picabia, in an attempt to publish L.H.O.O.Q. in his magazine 391 could not wait for the work to be sent from New York City, so with the permission of Duchamp, drew the moustache on Mona Lisa himself (forgetting the goatee). Picabia wrote underneath "Tableau Dada par Marcel Duchamp". Duchamp noticed the missing goatee. Two decades later, Duchamp corrected the omission on Picabia's replica, found by Jean Arp at a bookstore. Duchamp drew the goatee in black ink with a fountain pen, and wrote "Moustache par Picabia / barbiche par Marcel Duchamp / avril 1942".[1]

As was the case with a number of his readymades, Duchamp made multiple versions of L.H.O.O.Q. of differing sizes and in different media throughout his career, one of which, an unmodified black and white reproduction of the Mona Lisa mounted on card, is called L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved. The masculinized female introduces the theme of gender reversal, which was popular with Duchamp, who adopted his own female pseudonym, Rrose Sélavy, pronounced "Eros, c'est la vie" ("Eros, that's life").[2]

Primary responses to L.H.O.O.Q. interpreted its meaning as being an attack on the iconic Mona Lisa and traditional art,[8] a stroke of épater le bourgeois promoting the Dadaist ideals. According to one commentator:

The creation of L.H.O.O.Q. profoundly transformed the perception of La Joconde (what the French call the painting, in contrast with the Americans and Germans, who call it the Mona Lisa). In 1919 the cult of Jocondisme was practically a secular religion of the French bourgeoisie and an important part of their self image as patrons of the arts. They regarded the painting with reverence, and Duchamp's salacious comment and defacement was a major stroke of epater le bourgeois ("freaking out" or substantially offending the bourgeois).[9]

According to Rhonda R. Shearer the apparent reproduction is in fact a copy partly modelled on Duchamp's own face.[10]

Parodies of Duchamp's parodic Mona Lisa

[edit]Pre-Internet era

[edit]- Salvador Dalí created his Self Portrait as Mona Lisa[11] in 1954, referencing L.H.O.O.Q. in collaboration with Philippe Halsman. This work incorporated photographs of a wild-eyed Dalí showing his handlebar moustache and a handful of coins.[12][13]

- Icelandic painter Erró then incorporated Dalí's version of L.H.O.O.Q. into a 1958 composition that also included a film-still from Buñuel's Un Chien Andalou.

- Fernand Léger and René Magritte have also adapted L.H.O.O.Q., using their own iconography.[12]

Internet and computerized parodies

[edit]The use of computers permitted new forms of parodies of L.H.O.O.Q., including interactive ones.

One form of computerized parody using the Internet juxtaposes layers over the original, on a webpage. In one example, the original layer is Mona Lisa. The second layer is transparent in the main, but is opaque and obscures the original layer in some places (for example, where Duchamp located the moustache). This technology is described at the George Washington University Law School website.[14] An example of this technology is a copy of Mona Lisa with a series of different superpositions—first Duchamp's moustache, then an eye patch, then a hat, a hamburger, and so on.[15] The point of this technology (which is explained on the foregoing website for a copyright law class) is that it permits making a parody that need not involve making an infringing copy of the original work if it simply uses an inline link to the original, which is presumably on an authorized webpage.[16] According to the website at which the material is located:

The layers paradigm is significant in a computer-related or Internet context because it readily describes a system in which the person ultimately responsible for creating the composite (here, corresponding to [a modern-day] Duchamp) does not make a physical copy of the original work in the sense of storing it in permanent form (fixed as a copy) distributed to the end user. Rather, the person distributes only the material of the subsequent layers, [so that] the aggrieved copyright owner (here, corresponding to Leonardo da Vinci) distributes the material of the underlying [original Mona Lisa] layer, and the end user's system receives both. The end user's system then causes a temporary combination, in its computer RAM and the user's brain. The combination is a composite of the layers. Framing and superimposition of popup windows exemplify this paradigm.[17]

Other computer-implemented distortions of L.H.O.O.Q. or Mona Lisa reproduce the elements of the original, thereby creating an infringing reproduction, if the underlying work is protected by copyright.[18] Leonardo's rights in Mona Lisa would, of course, have long expired had such rights existed in his age.

See also

[edit]- List of works by Marcel Duchamp

- Mona Lisa replicas and reinterpretations

- Legacy of Mona Lisa

- Walker's L.H.O.O.Q.

- Gramogram, the artwork's title is an example of this type of pun

References

[edit]- ^ a b Marcel Duchamp 1887–1968, dadart.com

- ^ a b Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q. or La Joconde, 1964 (replica of 1919 original) Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena.

- ^ Rudolf E. Kuenzli, Dada and Surrealist Film, MIT Press, 1996, p. 47, ISBN 026261121X

- ^ More recent scholarship suggests that Duchamp laboriously altered the postcard before adding the moustache, including merging his own portrait with that of Mona Lisa. See Marco de Martino, "Mona Lisa: Archived 20 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine Who Is Hidden Behind the Woman With the Moustache?"

- ^ Coquelin, Ernest, Le Rire (2e éd.) / par Coquelin cadet; ill. de Sapeck, Bibliothèque nationale de France

- ^ Kristina, Seekamp (2004). "L.H.O.O.Q. or Mona Lisa". Unmaking the Museum: Marcel Duchamp's Readymades in Context. Binghamton University Department of Art History. Archived from the original on 12 September 2006.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Anne Collins Goodyear, James W. McManus, National Portrait Gallery (Smithsonian Institution), Inventing Marcel Duchamp: The Dynamics of Portraiture, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2009, contributors Janine A. Mileaf, Francis M. Naumann, Michael R. Taylor, ISBN 0262013002

- ^ See, for example, Andreas Huyssen, After the Great Divide: "It is not the artistic achievement of Leonardo that is mocked by moustache, goatee, and obscene allusion, but rather the cult object that the Mona Lisa had become in that temple of bourgeois art religion, the Louvre." (Quoted in Steven Baker, The Fiction of Postmodernity, p.49

- ^ L.H.O.O.Q. Archived 19 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine—Internet-Related Derivative Works.

- ^ Martino, Marco De (2003). "Mona Lisa: Who is Hidden Behind the Woman with the Mustache?". Art Science Research Laboratory. Archived from the original on 20 March 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ Dali Self Portrait as Mona Lisa

- ^ a b Peter Hedstrom, Peter Bearman (2009). The Oxford Handbook of Analytical Sociology. US: Oxford University Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-19-161523-8.

- ^ Baron, Robert A. (1973). "Mona Lisa Images for a Modern World". exhibition catalogue. Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ "L.H.O.O.Q.- Internet-Related Derivative Works". Archived from the original on 17 June 2020.

- ^ "L.H.O.O.Q. gif". Archived from the original on 2 August 2020.

- ^ See Perfect 10, Inc. v. Google, Inc.

- ^ L.H.O.O.Q., Internet–Related Derivative Works, Archived 19 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine George Washington University

- ^ "L.H.O.O.Q. 2 - Additional Demonstrative Materials". Archived from the original on 3 August 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Theodore Reff, "Duchamp & Leonardo: L.H.O.O.Q.-Alikes", Art in America, 65, January–February 1977, pp. 82–93

- Jean Clair, Duchamp, Léonard, La Tradition maniériste, in Marcel Duchamp: tradition de la rupture ou rupture de la tradition?, Colloque du Centre Culturel International de Cerisy-la-Salle, ed. Jean Clair, Paris: Union Générale d'Editions, 1979, pp. 117–44

External links

[edit]- L.H.O.O.Q. – Internet-Related Derivative Works Archived 19 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine