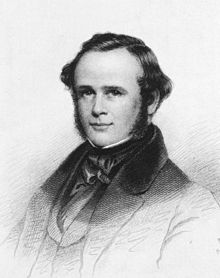

Horace Wells

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (November 2024) |

Horace Wells | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 21, 1815 Hartford, Vermont, U.S. |

| Died | January 24, 1848 (aged 33) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Dentist |

| Known for | Pioneering the use of nitrous oxide in anesthesia |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Wales |

| Signature | |

Horace Wells (January 21, 1815 – January 24, 1848) was an American dentist who pioneered the use of anesthesia in medicine, specifically the use of nitrous oxide (or laughing gas).

Early life

[edit]Wells was the first of three children of Horace and Betsy Heath Wells, born on January 21, 1815, in Hartford, Vermont.[1] His parents were well-educated and affluent landowners, which allowed him to attend private schools in New Hampshire and Amherst, Massachusetts. At the age of 19 in 1834, Wells began studying dentistry under a two-year apprenticeship in Boston.[2] The first dental school did not open until 1840 in Baltimore.[3]

At age 23, Wells published a booklet "An Essay on Teeth" in which he advocated for his ideas in preventive dentistry, particularly for the use of a toothbrush. In his booklet, he also described tooth development and oral diseases, where he mentioned diet, infection, and oral hygiene as important factors.[2][4]

Career

[edit]After he completed dental training in Boston, Wells opened his own office in Hartford, Connecticut on April 4, 1836. Between 1841 and 1845, Wells became a reputable dentist in Hartford, where he had many patients and attracted apprentices. Among his patients were respected members of society such as William Ellsworth, the governor of Connecticut. His three apprentices were John Mankey Riggs, C. A. Kingsbury, and William T. G. Morton. In 1843, Wells and Morton started a practice in Boston and Wells continued to instruct Morton.[3][5] John Riggs later became a partner of him.[citation needed]

Wells first witnessed the effects of nitrous oxide on December 10, 1844, when he and his wife Elizabeth attended a demonstration by Gardner Quincy Colton billed in the Hartford Courant as "A Grand Exhibition of the Effects Produced by Inhaling Nitrous Oxide, Exhilarating, or Laughing Gas." The demonstration took place at Union Hall, Hartford. During the demonstration, a local apothecary shop clerk Samuel A. Cooley became intoxicated by nitrous oxide. While under the influence, Cooley did not react when he struck his legs against a wooden bench while jumping around. After the demonstration, Cooley was unable to recall his actions while under the influence, but found abrasions and bruises on his knees. From this demonstration, Wells realized the potential for the analgesic properties of nitrous oxide, and met with Colton about conducting trials.[6][7]

The following day, Wells conducted a trial on himself by inhaling nitrous oxide and having John Riggs extract a tooth.[7] Upon a successful trial where he did not feel any pain, Wells went on to use nitrous oxide on at least 12 other patients in his office.[6][8] In 1844, Hartford did not have a hospital, so Wells sought to demonstrate his new findings in either Boston or New York. In January 1845 he chose to go to Boston where he had previously studied dentistry, and his former student and associate William Morton resided. Wells and Morton's practice had been dissolved in October 1844, but they remained in contact. Morton was enrolled in Harvard Medical School at the time and agreed to help Wells introduce his ideas, and provide him with dental instruments, although Morton was skeptical about the use of nitrous oxide.[7][9][10]

He gave a demonstration to medical students in Boston at the end of January 1845.[7] However, the gas was improperly administered, and the patient cried out in pain. The patient later admitted that although he cried out in pain, he remembered no pain and did not know when the tooth was extracted. It was later found that the gas is not as effective on both obese people and alcoholics—the patient was both. After the embarrassment of his failed demonstration, Wells immediately returned home to Hartford the next day. From this point on, his mental health declined, and his dental practice became sporadic.[1]

On February 5, 1845, Wells advertised his home for rent.[11] On April 7, 1845, Wells advertised in the Hartford Courant that he was going to dissolve his dental practice, and referred all his patients to Riggs, the man who had extracted his tooth.[12]

In October 1846, Morton gave a successful demonstration of ether anesthesia in Boston. Following Morton's demonstration, Wells published a letter accounting his successful trials in 1844 in an attempt to claim the discovery of anesthesia.[8] His efforts in establishing his claim were mostly unsuccessful.[6]

Despite his advertisement for dissolving his practice in April 1845, Wells sporadically continued his practice, with his last daybook entry being on November 5, 1845.[1]

Later years

[edit]Wells closed his office nine times and relocated six different times between 1836 and 1847. He closed his office due to ill health, although his physician could not find any physical cause for his non-specific complaints. He mentioned his recurring illness in a letter to his sister Mary Wells Cole in April 1837. He also became ill shortly after marrying Elizabeth Wales in 1838 and having his only son Charles Thomas Wells. During winter months, he would not write letters to any family or friends, except for his published letter in 1846 after Morton's ether demonstration.[1]

Wells definitively ended his dental practice in late 1845 and began selling shower baths for which he received a patent on November 4, 1846.[1] He also planned to sail to Paris to purchase paintings to resell in the United States. He traveled to Paris in early 1847, where he petitioned the Academie Royale de Medicine and the Parisian Medical Society for recognition in the discovery of anesthesia.[6]

Wells moved to New York City in January 1848, leaving his wife and young son behind in Hartford. He lived alone at 120 Chambers St in Lower Manhattan and began self-experimenting with ether and chloroform, and he became addicted to chloroform.[13] The effects of sniffing chloroform and ether were unknown.[14]

Wells rushed into the street on January 21, 1848, his 33rd birthday, and threw sulfuric acid over the clothing of two prostitutes. He was committed to New York's infamous Tombs Prison. As the influence of the drug waned, his mind started to clear and he realised what he had done. He asked the guards to escort him to his house to pick up his shaving kit.[14] He committed suicide in his cell on January 24, slitting his left femoral artery with a razor after inhaling an analgesic dose of chloroform.[15][16] He is buried at Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut.[17]

Legacy

[edit]Twelve days before his death, the Parisian Medical Society voted and honored him as the first to discover and perform surgical operations without pain. In addition, he was elected an honorary member and awarded an honorary MD degree.[12] However, Wells died unaware of these decisions.[2][10] Wells first voiced his concern for minimizing his patient's pain during dental procedures in 1841. He was known for caring about his patient's comfort.[1] During his time as a dentist, Wells advocated for regular check ups for dental hygiene, and also began the practice of pediatric dentistry in order to start dental care early.[citation needed]

The American Dental Association honored Wells posthumously in 1864 as the discoverer of modern anesthesia,[18] and the American Medical Association recognized his achievement in 1870.[19][20]

Hartford, Connecticut, has a statue of Horace Wells in Bushnell Park.[21][22]

A monument to Horace Wells was raised in the Place des États-Unis, Paris.[23]

The Baltimore College of Dental Surgery awarded him an honorary posthumous degree (Doctor of Dental Surgery, DDS.) on October 10, 1990.[7][24]

In popular culture

[edit]- The story of Dr. Wells' self-experimentation with drugs was explored in an episode of Science Channel's Dark Matters: Twisted But True in a story entitled "Jekyll vs Hyde", comparing it to the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.[citation needed]

- A full-length theatrical production, entitled Ether Dome, written by Elizabeth Egloff and directed by Michael Wilson centers around the story of Horace Wells' discovery of nitrous oxide as an anesthetic, as well as the life of his protege and partner, William Morton.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Dental anesthesiology

- Humphry Davy

- Crawford Long

- James Young Simpson

- Nathan Cooley Keep, Who was the tutor of both Horace wells and William Morton.[3]

Gallery

[edit]-

Horace Wells Plaque

-

Statue of Horace Wells in Hartford, Connecticut

-

Horace Wells Burial Monument (1909), Cedar Hills Cemetery, Hartford, Connecticut (Louis Potter, sculptor).

-

Statue of Horace Wells in Paris

-

Death Mask of Horace Wells

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Martin, Ramon F. (September 27, 2015). "An Examination of Horace Wells' Life as a Manifestation of Major Depressive and Seasonal Affective Disorders". Journal of Anesthesia History. 2 (1): 24. doi:10.1016/j.janh.2015.09.005. PMID 26898142.

- ^ a b c Jacobsohn, P.H. (1995). "Horace Wells: discoverer of anesthesia". Anesthesia Progress. 42 (3–4): 73–75. PMC 2148901. PMID 8967633.

- ^ a b c Guralnick, Walter C.; Kaban, Leonard B. (July 2011). "Keeping Ether "En-Vogue": The Role of Nathan Cooley Keep in the History of Ether Anesthesia". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 69 (7): 1892–1897. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.121. ISSN 0278-2391. PMID 21549472.

- ^ Wells, Horace (1838). An essay on teeth : comprising a brief description of their formation, diseases, and proper treatment. Cushing/Whitney Medical Library Yale University. Hartford : Printed for the author.

- ^ Gordon, Sarah H. (February 2000). "Wells, Horace". American National Biography Online. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1200962.

- ^ a b c d Finder, S.G. (1995). "Lessons from history: Horace Wells and the moral features of clinical contexts". Anesthesia Progress. 42 (1): 3–4. PMC 2148867. PMID 8934954.

- ^ a b c d e Haridas, Rajesh (November 2013). "Horace Wells' Demonstration of Nitrous Oxide in Boston". Anesthesiology. 119 (5): 1014–22. doi:10.1097/aln.0b013e3182a771ea. PMID 23962967. S2CID 37457024.

- ^ a b Wells, Horace, 1815-1848., “Letter of Horace Wells to the editor of the Hartford Daily Courant,” OnView, accessed May 27, 2024, https://collections.countway.harvard.edu/onview/items/show/18187.

- ^ Toucey, Isaac (1852). Discovery by the late Dr. Horace Wells of the applicability of nitrous oxyd gas, sulphuric ether and other vapors in surgical operations, nearly two years before the patented discovery of Drs. Charles T. Jackson and W.T.G. Morton. Cushing/Whitney Medical Library Yale University. Hartford : E. Geer. p. 40.

- ^ a b Smith, Truman; Ellsworth, Pickney Webster (1867). An inquiry into the origin of modern anaesthesia. Cushing/Whitney Medical Library Yale University. Hartford : Brown and Gross.

- ^ Wells, Horace; Menczer, Leonard F.; Wolfe, Richard J.; Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine; Historical Museum of Medicine and Dentistry, eds. (1994). I awaken to glory: essays celebrating the sesquicentennial of the discovery of anesthesia by Horace Wells, December 11, 1844-December 11, 1994. Boston, Mass: Published by the Boston Medical Library in the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Boston, in association with the Historical Museum of Medicine and Dentistry, Hartford. ISBN 978-0-88135-161-3.

- ^ a b Bunker, Emily, ed. (March 20, 2020). Horace and Elizabeth: Love and Death and Painless Dentistry: The Letters of Horace and Elizabeth Wells. Amazon Digital Services LLC - Kdp. ISBN 9798622825798.

- ^ Aljohani, Sara (September 2015). "Horace Wells and His House on 120 Chambers St in New York Ciity". Journal of Anesthesia History. 2 (1): 28–29. doi:10.1016/j.janh.2015.09.006. PMID 26898143.

- ^ a b Smith, Ken. Raw Deal. Blast Books: New York, 1998. pp. 62–63.

- ^ "Distressing And Singular Suicide". Springfield Republican. January 26, 1848.

- ^ "Suicide of Dr. Horace Wells, of Hartford, Connecticut, U.S". Providence Medical and Surgical Journal. 12 (11): 305–06. May 31, 1848. PMC 2487383. PMID 20794459.

- ^ "Horace Wells". Cedar Hill Cemetery Foundation. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

- ^ Archer, 200

- ^ Archer, 202

- ^ "Horace Wells". nndb.com. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^

Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Wells, Horace". Encyclopedia Americana.

Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Wells, Horace". Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ Archer, 174-176

- ^ Archer, 184-185

- ^ Khan, Iqbal Akhtar; Winters, Charles J. "Defeating Surgical Anguish: A Worldwide Tale of Creativity, Hostility, and Discovery" (PDF). Journal of Anesthesia and Patient Care. 3 (1): 12.

Sources

[edit]- Archer, W. Harry (June 1944). "The life and letters of Horace Wells". The Journal of the American College of Dentists. 11 (2).

Further reading

[edit]- Wells, Horace (1847). A History of the Discovery of the Application of Nitrous Oxide Gas, Ether, and Other Vapors to Surgical Operations. Hartford: J. Gaylord Wells.

Horace Wells.

- Fenster, Julie M. (2001). Ether Day – The Strange Tale of America's Greatest Medical Discovery and the Haunted Men Who Made It. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0060195231.

- Musto, David F., "They Inhaled", New York Times, August 12, 2001 (review of Ether Day)

- Downs, Michael (2018). The Strange and True Tale of Horace Wells, Surgeon Dentist: A Novel – Historical Fiction. Acre Books. ISBN 978-1946724045.