Dennis Eckersley

| Dennis Eckersley | |

|---|---|

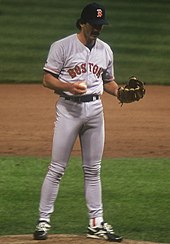

Eckersley at the 2008 All-Star Game Parade | |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: October 3, 1954 Oakland, California, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| April 12, 1975, for the Cleveland Indians | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 26, 1998, for the Boston Red Sox | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 197–171 |

| Earned run average | 3.50 |

| Strikeouts | 2,401 |

| Saves | 390 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 2004 |

| Vote | 83.2% (first ballot) |

Dennis Lee Eckersley (born October 3, 1954), nicknamed "Eck", is an American former professional baseball pitcher and color commentator. Between 1975 and 1998, he pitched in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Cleveland Indians, Boston Red Sox, Chicago Cubs, Oakland Athletics, and St. Louis Cardinals. Eckersley had success as a starter, but gained his greatest fame as a closer, becoming the first of two pitchers in major league history to have both a 20-win season and a 50-save season in a career.

Eckersley was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2004 in his first year of eligibility. He previously worked with NESN as a part-time color commentator for Red Sox broadcasts, and has also worked for Turner Sports as a game analyst for their Sunday MLB Games and MLB postseason coverage on TBS. He retired from NESN in 2022.

Early life

[edit]Eckersley grew up in Fremont, California, rooting for both the San Francisco Giants and the Oakland Athletics of Major League Baseball (MLB). Two of his boyhood heroes were the Giants' Willie Mays and Juan Marichal, and he later adopted Marichal's high leg kick pitching delivery.[1]

Eckersley attended Washington High School in Fremont, California. He played for the football team as a quarterback until his senior year, when he gave up football to protect his throwing arm from injury.[2] He won 29 games as a pitcher at Washington, throwing a 90-mile-per-hour (140 km/h) fastball and a screwball.[3]

Baseball career

[edit]Cleveland Indians (1975–1977)

[edit]The Cleveland Indians selected Eckersley in the third round of the 1972 MLB draft; he was disappointed that he was not drafted by the Giants. He made his major league debut on April 12, 1975. He was the American League Rookie Pitcher of the Year in 1975, compiling a 13–7 win–loss record and 2.60 earned run average (ERA). His unstyled long hair, moustache, and live fastball made him an instant and identifiable fan favorite. Eckersley pitched reliably over three seasons with the Indians.[citation needed]

On May 30, 1977, Eckersley threw a no-hitter against the California Angels at Cleveland Stadium. He struck out 12 batters and only allowed two to reach base, Tony Solaita on a walk in the first inning and Bobby Bonds on a third strike that was a wild pitch.[4] He earned his first All-Star Game selection that year and finished the season with a 14–13 win–loss record.[5]

Boston Red Sox (1978–1984)

[edit]The Indians traded Eckersley and Fred Kendall to the Boston Red Sox for Rick Wise, Mike Paxton, Bo Díaz, and Ted Cox on March 30, 1978. Over the next two seasons, Eckersley won a career-high 20 games in 1978 and 17 games in 1979, with a 2.99 ERA in each year.[5] However, during the remainder of his tenure with Boston, from 1980 to 1984, Eckersley pitched poorly. His fastball had lost some steam, as demonstrated by his 43–48 record with Boston. He later developed a very effective slider.

Chicago Cubs (1984–1986)

[edit]On May 25, 1984, the Red Sox traded Eckersley with Mike Brumley to the Chicago Cubs for Bill Buckner, one of several mid-season deals that helped the Cubs to their first postseason appearance since 1945. He won 10 games and lost 8, with a 3.03 ERA.

Eckersley remained with the Cubs in 1985, when he posted an 11–7 won-lost record with two shutouts (the last two of his career). Eckersley's performance deteriorated in 1986, when he posted a 6–11 record with a 4.57 ERA. After the season, he checked himself into a rehabilitation clinic to treat alcoholism.[6] Eckersley noted in Pluto's book[citation needed] that he realized the problem he had after family members videotaped him while drunk and played the tape back for him the next day. During his Hall of Fame speech he recalled that time in his life, saying "I was spiraling out of control personally. I knew I had come to a crossroads in my life. With the grace of God, I got sober and I saved my life."[7]

Oakland Athletics (1987–1995)

[edit]Eckersley was traded again on April 3, 1987, to the Oakland Athletics, where manager Tony La Russa intended to use him as a set-up pitcher or long reliever. Indeed, Eckersley started two games with the A's before an injury to then-closer Jay Howell opened the door for Eckersley to move into the closer's role. He saved 16 games in 1987 and then established himself as a dominant closer in 1988 by recording a league-leading 45 saves. Eckersley recorded 4 saves against the Red Sox in the regular season, and he dominated once more by recording saves in all four games as the A's swept the Red Sox in the 1988 ALCS. (which was matched by Greg Holland in the 2014 ALCS), but he found himself on the wrong end of Kirk Gibson's 1988 World Series home run (Eckersley himself first coined the phrase "walk-off home run" to describe that moment) as the A's lost to the Dodgers in 5 games.

In the 1989 World Series he secured the victory in Game Two, and then earned the save in the final game of the Series, as the A's swept the San Francisco Giants in four games.

Eckersley was the most dominant closer in the game from 1988 to 1992, finishing first in the A.L. in saves twice, second two other times, and third once. He saved 220 games during the five years and never posted an ERA higher than 2.96. He gave up five earned runs in the entire 1990 season, resulting in a 0.61 ERA. Eckersley's control, which had always been above average even when he was not otherwise pitching well, became his trademark; he walked only three batters in 57.2 innings in 1989, four batters in 73.1 innings in 1990, and nine batters in 76 innings in 1991. Between August 7, 1989, and June 10, 1990, Eckersley appeared in 41 games without walking a single batter, setting a record which still stands as of 2020[update] and surpassing the previous mark set by Lew Burdette 23 years earlier.[8] In his 1990 season, Eckersley became the first relief pitcher in baseball history to have more saves than baserunners allowed (48 saves, 41 hits, 4 walks, 0 hit by pitch). Perhaps interestingly, rounded to three decimal places, he had the same walks plus hits per innings pitched and ERA: both were 0.614.

Eckersley was the American League's Most Valuable Player and Cy Young Award winner in 1992, a season in which he posted 51 saves. Only two relievers had previously accomplished the double feat: Rollie Fingers in 1981 and Willie Hernández in 1984. In the 1992 American League Championship Series against the Toronto Blue Jays, during Game 4 in what some considered the turning point in the series that the Jays won, Eckersley gave up a game-tying 2-run home run to Roberto Alomar and his team eventually lost 7–6 in 11 innings.

Eckersley's numbers slipped following 1992: although he still was among the league leaders in saves, his ERA climbed sharply, and his number of saves never climbed above 36.

On September 16, 1993, in a game against the Minnesota Twins, Eckersley allowed Dave Winfield's 3,000th career hit.

After the 1994 season, the Athletics elected not to exercise a $4 million option on Eckersley, making him a free agent. The team indicated that it would be interested in signing him at a lower salary.[9] Oakland signed him to a one-year contract in early April 1995. His contract was the first major league deal after a three-month signing ban resulting from a labor dispute between owners and the players union.[10]

St. Louis Cardinals (1996–1997)

[edit]When La Russa left the Athletics after the 1995 season to become the St. Louis Cardinals' new manager, he arranged to bring Eckersley along with him.[clarification needed] Eckersley continued in his role as closer and remained one of the league's best, with 66 saves in two seasons in St. Louis.[11]

Return to Red Sox (1998)

[edit]

Following the 1997 season, he signed with the Red Sox for a final season, serving as a set-up man for Tom Gordon, as Boston qualified for the AL playoffs.[12]

Eckersley announced his retirement in December 1998. He commented on his career, saying, "I had a good run. I had some magic that was with me for a long time, so I know that I was real lucky to not have my arm fall off for one thing, and to make it this long physically is tough enough. But to me it's like you're being rescued too when your career's over. It's like, 'Whew, the pressure's off'."[13]

Career statistics

[edit]| W | L | PCT | ERA | G | GS | CG | SHO | SV | IP | H | ER | R | HR | BB | SO | WP | HBP |

| 197 | 171 | .535 | 3.50 | 1071 | 361 | 100 | 20 | 390 | 3285.2 | 3076 | 1278 | 1382 | 347 | 738 | 2401 | 75 | 28 |

He retired with a career 197–171 win–loss record, a 3.50 ERA and 390 saves. As of the end of the 2023 season, Eckersley's career saves total ranks ninth on the all-time saves list.[14] When he retired, Eckersley had appeared in more games (1,071) than any other pitcher in major league history, though he ranks fifth all-time through the 2023 season.[15][16]

Pitching style

[edit]Eckersley's unusual delivery utilized a high leg kick along with a long, pronounced sidearm throwing motion. He had pinpoint accuracy, and fellow Hall of Famer Goose Gossage said of him, "He could hit a gnat in the butt with a pitch if he wanted to.” Eckersley was aggressive and animated on the mound, and he was known for his intimidating stare and pumping his fist after a strikeout.[17] As a starter, Eckersley was able to throw four pitches for strikes, but as a reliever he narrowed his repertoire to two pitches; a sinker and a backdoor slider.[18]

Post-playing career

[edit]In 1999, he ranked Number 98 on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players.[19] He was named to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.[20] On January 6, 2004, he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility, with 83.2% of the votes.[21] On August 13, 2005, Eckersley's uniform number (43) was officially retired by the Oakland Athletics.[22] The baseball field at his alma mater, Washington High School, has been named in his honor.[23]

In 2017, Eckersley rejoined the Athletics as the special assistant to Dave Kaval, the team's president.[24]

Broadcasting

[edit]Eckersley began working as a studio analyst and color commentator for the Boston Red Sox on NESN in 2002. "Eck" became known for his easy-going manner and his own baseball vernacular, with Red Sox Nation attempting to keep up via "The Ecktionary," a defining list of his on-air sayings.[25]

In the spring of 2009, when regular NESN commentator Jerry Remy took time off for health reasons, Eckersley filled in for him, providing color commentary alongside play-by-play announcer Don Orsillo.[26] Eckersley was the primary substitute for Remy when he was unavailable, including filling in for the final two months of the 2013 season, when Remy took extended time off due to the murder indictment of his son, Jared. Eckersley continued to work with Orsillo's successor, Dave O'Brien, for various Red Sox games, and often worked with Remy and O'Brien in a three-man booth prior to Remy's death in 2021.

Eckersley also worked with TBS as a studio analyst from 2008 to 2012. In 2013, Eckersley moved to the booth with TBS, calling Sunday games for the network and also providing postseason analysis from the booth. In the 2017 postseason, he worked with Brian Anderson, Joe Simpson and Lauren Shehadi.[27][28]

Eckersley announced his retirement from NESN on August 8, 2022.[29][30] In a statement released by NESN, he said:

After 50 years in Major League Baseball, I am excited about this next chapter of my life. I will continue to be an ambassador for the club and a proud member of Red Sox Nation while transitioning to life after baseball alongside my wife Jennifer, my children and my grandchildren. I’m forever grateful to NESN, the Red Sox, my family and the fans for supporting me throughout my career and through this decision and I look forward to remaining engaged with the team in a variety of capacities for years to come.[29]

During an interview with The Boston Globe, Eckersley said, "I've been thinking about this for a long time. Not that it matters, but it's kind of a round number, leaving. I started in pro ball in '72, when I was a 17-year-old kid right out of high school. Fifty years ago ... So it's time."[31] Following his announcement, Sean McGrail, NESN president and CEO said that NESN was "...fortunate that Dennis has been a part of our Red Sox coverage ... His unbridled passion, nuanced insights and Eck humor will be dearly missed and we are thankful for his many contributions to NESN. We wish him the best as he embarks on this next chapter of his life as a grandfather, father, husband and member of Red Sox Nation."[29] Eckersley's final Red Sox broadcast as a NESN commentator was October 5, 2022.[32]

Personal life

[edit]Eckersley married his first wife Denise in 1973 and they had a daughter, Mandee Eckersley. Denise left him for Rick Manning, his then–Cleveland Indians teammate, in 1978; the affair precipitated Eckersley's trade to the Red Sox that year.[33] Two years later, Eckersley married model Nancy O'Neil.[6] They adopted two children together, a son Jake and a daughter Alexandra.[34] They divorced shortly after his retirement from baseball.[35] His third wife, Jennifer, is a former lobbyist and manages Eckersley's business and charitable affairs.[36]

During the first half of his career, Eckersley had problems with alcohol; he became sober in January 1987.[37]

An MLB Network documentary about Eckersley, titled Eck: A Story of Saving, premiered on December 13, 2018.[38]

In December 2022, Eckersley's adopted daughter Alexandra, a homeless person, was arrested on suspicion of abandoning her newborn in a wooded area in 18 degree weather and misleading authorities as to the infant's whereabouts.[39] Alexandra had been homeless since 2018 and suffering from addiction and mental health issues.[40]

See also

[edit]- Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame

- List of Major League Baseball annual saves leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball no-hitters

References

[edit]- ^ "Eck's long haul to fame". San Francisco Chronicle. July 11, 2004. Archived from the original on December 29, 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ Jim Ison. Mormons in the Major Leagues. p.37

- ^ "This Series has loads of hometown heroes". Star-News. October 16, 1989. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ "Eckersley: No-hitter". St. Petersburg Times. May 31, 1977. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ a b "Dennis Eckersley Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Gammons, Peter (December 12, 1988). "One Eck of a Guy". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Kekis, John (July 26, 2004). "Eckersley gives stirring speech as he and Molitor enter Hall". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ "Pitching Streak Finder". Stathead.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ "Eckersley a free agent, but A's want him back". Los Angeles Times. October 21, 1994. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ "Eckersley re-signs to break the ice". Los Angeles Times. April 4, 1995. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ "Dennis Eckersley Stats". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1998 Boston Red Sox Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Pitcher Dennis Eckersley retires after a 24-year career". Rome News-Tribune. December 11, 1998. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Saves". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Games Played". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ Verducci, Tom, Kennedy, Kostya (December 21, 1998). "Eckstraordinary". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith, Claire (May 19, 1992). "ON BASEBALL; Eckersley First Rate In His Second Career". The New York Times. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ Falkner, David (October 12, 1989). "On Field or Off, Eckersley Battles". The New York Times. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players by The Sporting News (1998)". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ "The All-Century Team". MLB.com. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ Blum, Ronald (January 7, 2004). "Molitor, Eckersley each elected to Hall of Fame on first ballot". Peninsula Clarion. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ Bowles, C. J. "Forever No. 43". MLB.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ Leatherman, Gary (September 5, 2006). "Dennis Eckersley Field dedication set for Friday at WHS". Tri-City Voice. Retrieved September 20, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Dennis Eckersley returns to A's in a Special way". March 31, 2017.

- ^ "Webster's New World Ecktionary". Bleacher Report. June 2, 2009. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Eckersley to fill in for Remy Archived May 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine NESN.com, May 4, 2009

- ^ "Dennis Eckersley". August 15, 2016.

- ^ "Brian Anderson will call the NLCS on TBS due to Ernie Johnson's NBA commitments". October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Dennis Eckersley Announces Final Red Sox Season As NESN Color Commentator". NESN. August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Dennis Eckersley retiring from NESN Red Sox broadcasts at season's end". CBS News. August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Dennis Eckersley to Retire From Red Sox Booth After Season". WBTS-CD. August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ Dudek, Greg (October 5, 2022). "NESN's Dennis Eckersley Gives Emotional, Tear-Filled Send-Off". NESN.com. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ The Curse of Rocky Colavito: A Loving Look at a Thirty-Year Slump, Terry Pluto, Gray & Company, ISBN 978-1-59851-035-5, pp. 167–169

- ^ Kroichick, Ron (May 24, 1997). "At 42, Time Standing Still for the Eck". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Doyle, Paul (July 25, 2004). "A closer who needed a save". Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ "Alumni Profiles: Jennifer Eckersley '93". Heidelberg University. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Finn, Chad (July 16, 2019). "'I got lucky, man.' Dennis Eckersley on surviving his tough times". The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Finn, Chad (November 29, 2018). "MLB Network to premiere Dennis Eckersley documentary". The Boston Globe. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- ^ Botelho, Jessica (December 28, 2022). "Daughter of MLB Hall of Fame pitcher accused of abandoning newborn baby in woods". 3 News. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ Duckler, Ray (May 4, 2019). "A former star pitcher, his daughter and the reality that homelessness can happen to anyone". Concord Monitor. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Finn, Chad (August 30, 2018). "What the heck is The Eck talking about?". Boston.com. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Dennis Eckersley at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from MLB, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Dennis Eckersley at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- 1954 births

- Living people

- American League All-Stars

- American League Championship Series MVPs

- American League Most Valuable Player Award winners

- American League saves champions

- American sportsmen

- Baseball players from Oakland, California

- Boston Red Sox announcers

- Boston Red Sox players

- Chicago Cubs players

- Cleveland Indians players

- Cy Young Award winners

- Major League Baseball broadcasters

- Major League Baseball pitchers

- Major League Baseball players with retired numbers

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Oakland Athletics players

- Pawtucket Red Sox players

- Reno Silver Sox players

- San Antonio Brewers players

- St. Louis Cardinals players

- 20th-century American sportsmen