Jacinda Ardern

The Right Honourable Dame Jacinda Ardern | |

|---|---|

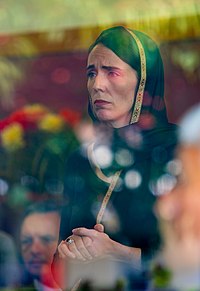

Ardern in August 2022 | |

| 40th Prime Minister of New Zealand | |

| In office 26 October 2017 – 25 January 2023 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II Charles III |

| Governor-General | Patsy Reddy Cindy Kiro |

| Deputy | Winston Peters Grant Robertson |

| Preceded by | Bill English |

| Succeeded by | Chris Hipkins |

| 17th Leader of the Labour Party | |

| In office 1 August 2017 – 22 January 2023 | |

| Deputy | Kelvin Davis |

| Preceded by | Andrew Little |

| Succeeded by | Chris Hipkins |

| 36th Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 1 August 2017 – 26 October 2017 | |

| Deputy | Kelvin Davis |

| Preceded by | Andrew Little |

| Succeeded by | Bill English |

| 17th Deputy Leader of the Labour Party | |

| In office 1 March 2017 – 1 August 2017 | |

| Leader | Andrew Little |

| Preceded by | Annette King |

| Succeeded by | Kelvin Davis |

| Member of the New Zealand Parliament for Mount Albert | |

| In office 8 March 2017 – 15 April 2023 | |

| Preceded by | David Shearer |

| Succeeded by | Helen White |

| Majority | 21,246 |

| Member of the New Zealand Parliament for the Labour Party List | |

| In office 8 November 2008 – 8 March 2017 | |

| Succeeded by | Raymond Huo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jacinda Kate Laurell Ardern 26 July 1980 Hamilton, New Zealand |

| Political party | Labour |

| Domestic partner | Clarke Gayford (2013–present; engaged) |

| Children | 1 |

| Parents | Ross Ardern (father) |

| Alma mater | University of Waikato (BCS) |

Dame Jacinda Kate Laurell Ardern[1] GNZM (/dʒəˈsɪndə ˈɑːrdɜːrn/;[2] born 26 July 1980) is a New Zealand politician. She was the 40th Prime Minister of New Zealand and the Leader of the Labour Party from October 2017 to January 2023. She was elected to the House of Representatives in 2008. She was the member of Parliament (MP) for Mount Albert from 2017 to 2023.[3]

Ardern was born in Hamilton and grew up in Morrinsville and Murupara. After graduating from the University of Waikato in 2001, Ardern began her career working as a researcher for Prime Minister Helen Clark. She later worked in London in the Cabinet Office, and was elected president of the International Union of Socialist Youth.[4][5] Ardern was first elected as an MP in the 2008 general election, when Labour lost control after nine years. She was later elected to represent the Mount Albert electorate in a by-election in February 2017.

Ardern was elected Deputy Leader of the Labour Party on 1 March 2017, after the resignation of Annette King. Just five months later, after Labour's leader Andrew Little resignation, Ardern was elected as party leader.[6] She led her party to win 14 seats at the 2017 general election on 23 September, winning 46 seats to the National Party's 56.[7] After working with New Zealand First, a minority coalition government with Labour and New Zealand First was formed, supported by the Green Party. Ardern became Prime Minister and she was sworn in by the governor-general on 26 October 2017.[8] She became the world's youngest female head of government at age 37.[9] Ardern later became the world's second elected head of government to give birth while in office when her daughter was born in June 2018.[10]

Ardern calls herself a social democrat and a progressive.[11][12] Her government has focused on the New Zealand housing crisis, child poverty, and social inequality. In March 2019, she became popular because of her leadership during the Christchurch mosque shootings and for introducing strict gun laws in response. For much of 2020, she also became popular for the country's response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Ardern led the Labour Party to a historic victory in the 2020 general election, winning a majority of 65 seats in Parliament.

In January 2023, Ardern announced she would resign as Labour leader and prime minister within a few weeks.[13] She left office on 25 January and was replaced by Chris Hipkins.[14]

Early life

[change | change source]Ardern was born in Hamilton, New Zealand,[15] and grew up as a Mormon.[16][17] She was raised in Morrinsville and Murupara, where her father, Ross Ardern, worked as a police officer.[18] Her mother, Laurell Ardern (née Bottomley), worked as a school catering assistant.[19][20] She studied at Morrinsville College,[21] where she was the student representative on the school's board.[22] She later went to the University of Waikato, graduating in 2001 with a Bachelor of Communication Studies (BCS) in politics and public relations.[23]

Ardern became interested in politics because her aunt asked her to help her with campaigning for New Plymouth MP Harry Duynhoven during his re-election campaign at the 1999 general election.[24]

Ardern joined the Labour Party at the age of 17 and became a senior figure in the Young Labour party of the party.[25] After graduating from university, she spent time working in the offices of Phil Goff and of Helen Clark as a researcher.[23] She volunteered at a soup kitchen in New York City in the United States[26] and worked on a workers' rights campaign.[27] Ardern moved to London, England where she became a senior policy adviser for British prime minister Tony Blair.[4][28] Ardern also worked at the Home Office to help with a review of policing in England and Wales.[23]

In early 2008, Ardern was elected President of the International Union of Socialist Youth.[5]

Member of Parliament, 2008–2023

[change | change source]Early activities

[change | change source]Ahead of the 2008 election, Ardern was ranked 20th on Labour's party list.[29] She would soon return from London to campaign full-time for a seat in the New Zealand Parliament.[30] She also became Labour's candidate for the safe National electorate of Waikato. Ardern lost the election, but entered Parliament as a list MP because of her high ranking in the party list.[29] She became the youngest sitting MP in Parliament.[31]

Opposition Leader Phil Goff promoted Ardern to the front bench, naming her Labour's spokesperson for Youth Affairs and for Justice (Youth Affairs).[32] She made appearances on TVNZ's Breakfast programme as part of the "Young Guns" feature, alongside National MP and future National Party leader, Simon Bridges.[33]

Ardern ran for the parliament seat of Auckland Central for Labour in the 2011 general election, running against incumbent National MP Nikki Kaye for National and Greens candidate Denise Roche.[34] She lost to Kaye by 717 votes.[34] However, she returned to Parliament because of her party list ranking, on which she was ranked 13th.[34][35]

After Goff resigned from the Party leadership, Ardern supported David Shearer for party leader.[32] She was promoted to the fourth-ranking position in his Shadow Cabinet on 19 December 2011, becoming a spokesperson for social development under the new leader.[32] Ardern ran again in Auckland Central at the 2014 general election.[36] She again finished second, but increased her own vote and lowered Kaye's majority from 717 to 600.[36] She was soon ranked 5th on Labour's list and because of this, Ardern still returned to Parliament where she became Shadow spokesperson for Justice, Children, Small Business, and Arts & Culture under new leader Andrew Little.[37]

2017 Mount Albert by-election

[change | change source]Ardern later ran for the Labour nomination for the Mount Albert by-election to be held in February 2017.[38] The by-election was held because of the resignation of David Shearer.[38] When nominations for the Labour Party closed on 12 January 2017, Ardern was the only nominee and was selected.[39] On 21 January, Ardern took part of the 2017 Women's March, a worldwide protest in opposition to Donald Trump, the newly inaugurated President of the United States.[39] She was confirmed as Labour's candidate at a meeting on 22 January.[40][41] Ardern won a landslide victory, winning 77 per cent of votes cast in the preliminary results.[42][43]

Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, 2017

[change | change source]Following her win in the by-election, Ardern was elected as Deputy Leader of the Labour Party on 7 March 2017, after the resignation of Annette King.[44] Ardern's vacant list seat was taken by Raymond Huo.[45] However, Ardern would remain as Deputy Leader for exactly five months because she was elected Leader of the Labour Party in August.[46]

Leader of the Opposition, 2017

[change | change source]

On 1 August 2017, just seven weeks before the 2017 general election, Ardern became Leader of the Labour Party and also Opposition Leader, after the resignation of Andrew Little.[47][46] Ardern was confirmed in an election to choose a new leader at a meeting the same day.[46] At 37, Ardern became the youngest leader of the Labour Party in its history.[16] She is also the second female leader of the party after Helen Clark.[48] At first, Little had talked to Ardern on 26 July and said he thought she should take over as Labour leader.[49] Ardern said no and told him to remain as leader.[49]

At her first press conference after her election as leader, she said that the upcoming election campaign would be positive.[25] After her appointment, the party had a large amount of public campagin donations, reaching NZ$700 per minute at its highest.[50] When Ardern became party leader, Labour rose in opinion polls.[49] By late August the party had reached 43 per cent as well as beating the National Party in opinion polls for the first time in over a decade.[49] Critics said that her ideas were similar to Andrew Little's and believed that Labour's sudden increase in popularity was because of her youth and good looks.[16]

In mid-August 2017, Ardern said that a Labour government would create a tax working group to look for the chance of increasing taxes for the wealthy and lowering them for middle-class working families.[51][52] This idea became unpopular and Ardern said that her tax plan would not be pushed in a first term of Labour government.[53][54] Minister of Finance Steven Joyce found that the Labour Party had problems in its $11.7 billion budget.[55][56]

The Labour and Green parties' proposed water and pollution taxes also became unpopular from farmers.[57] On 18 September 2017, farmers and lobbyists protested against the taxes in Ardern's hometown of Morrinsville.[58][57] During the protest, one farmer had a sign calling Ardern a "pretty Communist".[58] This was criticised as sexist by former Prime Minister Helen Clark.[58]

In the final days of the general election campaign, the National Party took a slight lead over the Labour Party.[59]

2017 general election

[change | change source]In the 2017 general election held on 23 September 2017, Ardern was re-elected to her Mount Albert electorate seat by 15,264 votes.[60] Preliminary results from the general election showed that Labour received 35.79 per cent of the party vote to National's 46.03 per cent.[61][62] After more votes were counted, Labour increased its votes to 36.89% while National dropped back to 44.45%.[63] Labour gained 14 seats, increasing its parliamentary representation to 46 seats.[63] This was the best result for the party since losing power in 2008.[63]

After the election, Ardern and Deputy Leader Kelvin Davis began talks with the Greens and New Zealand First parties about forming a coalition against National Party which did not haven enough seats for a majority.[63][64][65] On 19 October 2017, New Zealand First leader Winston Peters agreed to form a coalition with Labour,[8] making Ardern the next Prime Minister.[66][67] The Green Party also supported the coalition.[68] Ardern named Peters as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs.[69] She also gave New Zealand First five posts in her government, with Peters and three other ministers in her Cabinet.[69][70]

Prime Minister, 2017–2023

[change | change source]First term, 2017–2020

[change | change source]

Ardern was sworn-in as the 40th Prime Minister of New Zealand by Governor-General Dame Patsy Reddy on 26 October 2017.[71] Ardern promised that her government would have empathy and be strong.[72]

Ardern became New Zealand's third female Prime Minister after Jenny Shipley (1997–1999) and Helen Clark (1999–2008).[73][74] She is a member of the Council of Women World Leaders.[75] At aged 37, Ardern is also the youngest person to become New Zealand's head of government since Edward Stafford, who became premier in 1856.[76]

On 19 January 2018, Ardern announced that she was pregnant, and that Winston Peters would become acting Prime minister for six weeks after the birth.[77] Following the birth of a daughter, she took her maternity leave from 21 June to 2 August 2018.[78][79][80]

Domestic policies

[change | change source]Ardern focused on cutting child poverty in New Zealand by half within a ten years.[81] In July 2018, Ardern announced the start of her government's flagship Families Package.[82] The package would increase paid parental leave to 26 weeks and introduced a $60 per-week universal BestStart Payment for low and middle-income families with young children.[83] In 2019, the government a school lunches pilot programme to help cut child poverty numbers.[84] She also increased welfare benefits by $25,[85] expanding free doctor's visits and giving free menstrual hygiene products in schools.[86]

Ardern's government added increases to the country's minimum wage over a period of time.[87][88] Her government also cancelled the National Party's planned tax cuts, saying instead it would focus on healthcare and education.[89] The first year of post-secondary education was made free on 1 January 2018 and the government agreed to increase primary teachers' pay by 12.8 (for beginning teachers) and 18.5 per cent by 2021.[90] Even thought the Labour Party campaigned on a capital gains tax for the last three elections, Ardern promised in April 2019 that the government would not pass a capital gains tax under her leadership.[91][92]

On 2 February 2018, Ardern went to Waitangi for the annual Waitangi Day commemoration and she stayed in Waitangi for five days.[93] Ardern became the first female Prime Minister to speak from the top marae.[93] Her visit was popular among Māori leaders, with commentators seeing the difference between her performance to the Prime Ministers before her.[93][94]

In September 2019, she was criticised for her handling of an allegation of sexual assault against a Labour Party staffer.[95] Ardern said she had been told the allegation did not involve sexual assault or violence before a report about the incident was published in The Spinoff on 9 September.[95] Many did not believe this as one journalist found that Ardern's claim was hard to believe.[96][97]

Ardern does not support putting people who use cannabis in prison and promised to hold a referendum on the issue.[98] A non-binding referendum to legalise cannabis was held at the same time of the 2020 general election.[99] Ardern said she used cannabis when she was young during a televised debate before the election.[99] In the referendum, voters did not support the proposed cannabis legalisation and many found that Ardern not supporting the 'yes' campaign may have caused the legalisation's defeat.[100]

Foreign policies

[change | change source]

On 5 November 2017, Ardern made her first official trip to Australia, where she met Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull for the first time.[101] Relations between the two countries had not been good because of Australia's treatment of New Zealanders living in the country, and shortly before taking office.[101] Turnbull promised to work with Ardern and not have their political beliefs in the way.[102]

In November 2017, Ardern announced that the government would being part of the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations even though the Green Party did not support it.[103] On 25 October 2018, New Zealand ratified the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership,[104] which Ardern had described as being better than the original TPP agreement.[105]

In December 2017, Ardern supported for a United Nations resolution criticising U.S. President Donald Trump's decision to recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.[106]

On 24 September 2018, Ardern became the first female head of government to go to the United Nations General Assembly meeting with her baby present.[107][108] Her address to the General Assembly on 27 September had positive support from the United Nations where she talked about climate change, for the equality of women, and for kindness.[109]

In October 2018, Ardern criticized China for its Xinjiang re-education camps and human rights abuses against the Uyghur Muslim minority in the country.[110][111] Ardern was also worried about the treatment of the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.[112] In November 2018, she met with Myanmar's leader Aung San Suu Kyi and offered any help New Zealand could give to solve the Rohingya crisis.[113]

On 23 September 2019, at a United Nations summit in New York City, Ardern had her first formal meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump.[114] She said that Trump was interested in New Zealand's gun buyback policy.[114][115]

On 28 February 2020, Ardern criticised Australia's policy of deporting New Zealanders, many of which had lived in Australia but had not become Australian citizens.[116][117][118]

Christchurch mosque shootings

[change | change source]

On 15 March 2019, 51 people were fatally shot and 49 injured in two mosques in Christchurch.[121] In a statement broadcast on television, Ardern said that the shootings had been carried out by suspects with "extremist views" that have no place in New Zealand, or anywhere else in the world.[122] She also called it as a well-planned terrorist attack.[121]

She announced a time of national mourning and created a national condolence book that she opened in the capital, Wellington.[123] She also travelled to Christchurch to meet first responders and families of the victims.[124] In an address at the Parliament, she said that she would never say the name of the attacker: "Speak the names of those who were lost rather than the name of the man who took them ... he will, when I speak, be nameless".[125] Ardern became popular in the country and the world for her response to the shootings.[126][127][128][129] A photograph of her hugging a member of the Christchurch Muslim community with the word "peace" in English and Arabic was projected onto the Burj Khalifa.[130] A 25-metre (82 ft) mural of this photograph was opened in May 2019.[131]

In response to the shootings, Ardern said her government's plans to create stricter gun laws.[132] She said that the attack had shown many weaknesses in New Zealand's gun law.[133] On 10 April 2019, less than one month after the attack, the New Zealand Parliament passed a law that bans most semiautomatic weapons and assault rifles, parts that turn guns into semiautomatic guns, and higher capacity magazines.[134]

On 15 May 2019, Ardern and French President Emmanuel Macron co-chaired the Christchurch Call summit to bring together countries and tech companies.[135] The goal was to stop social media's role in organising and promoting terrorism and violent extremism.[135]

COVID-19 response

[change | change source]

On 14 March 2020, Ardern announced the government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic in New Zealand.[137] She said that the government would be requiring anyone entering the country from midnight 15 March to isolate themselves for 14 days.[137] She said the new rules will make it harder for people to travel to the country.[138] On 19 March, Ardern said that New Zealand's borders would be closed to all non-citizens and non-permanent residents, after 11:59 pm on 20 March (NZDT).[139] Ardern announced that New Zealand would move to a nationwide lockdown, at 11:59 pm on 25 March.[140]

National and international media had positive responses about her leadership and quick response to the outbreak in New Zealand.[141][142] The Washington Post said her interviews, press conferences and social media is an example of what a leader should do.[143] In mid-April 2020, two people sued Ardern and other government officials, saying that the lockdown limited their freedoms and was made for political reasons.[144] The lawsuit was dismissed.[145]

On 5 May 2020, Ardern and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced plans to create a trans-Tasman COVID-safe travel zone that would allow residents from both countries to travel freely without travel restrictions.[146][147]

Opinion polls showed the Labour Party with nearly 60 per cent support.[148][149] In May 2020, 59.5 per cent of citizens found Ardern as "preferred prime minister".[150][151]

2020 general election

[change | change source]In the 2020 general election, Ardern led her party to a landslide victory.[152] Her party won an overall majority of 65 seats in the 120-seat House of Representatives, and 50 per cent of the party vote.[153] She was also re-elected to her seat on the Mount Albert electorate by 21,246 votes.[154][155] Ardern said her landslide victory was because of her response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic impacts it has had.[156]

Second term, 2020–2023

[change | change source]Domestic affairs

[change | change source]

On 2 December 2020, Ardern declared a climate change emergency in New Zealand and promised that the country would be carbon neutral by 2025 in a parliamentary motion.[157] She said that the public will be required to buy only electric or hybrid vehicles.[157] This was supported by the Labour, Green, and Māori parties but was opposed by the opposition National and ACT parties.[157][158]

In response to the housing affordability issues, Ardern proposed the removal of the interest rate tax-deduction, lifting Housing Aid for first home buyers, giving away infrastructure funds and expand the Bright Line Test from five to ten years.[159][160]

On 14 June 2021, Ardern said that the New Zealand Government would apologise for the Dawn Raids.[161][162] She formally apologised for the raids in August 2021.[163]

COVID-19 pandemic

[change | change source]On 12 December 2020, Prime Minister Ardern and Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown announced that a travel route between New Zealand and the Cook Islands would be created in 2021.[164] It would allow a two-way quarantine-free travel between the two countries.[164] On 14 December, Prime Minister Ardern confirmed that the New Zealand and Australian Governments had agreed to create a travel route between the two countries the following year.[165] On 17 December, Ardern also announced that the government had bought two more COVID-19 vaccines from the pharmaceutical companies AstraZeneca and Novavax for New Zealand and its Pacific partners.[166]

On 26 January 2021, Ardern stated that New Zealand's borders would remain closed to most non-citizens and non-residents until New Zealand citizens have been "vaccinated and protected".[167] A month later, her government created a vaccination programme.[168] In August 2021, after one person tested positive for the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant, the country went under lockdown again.[169]

On 29 January 2022, Ardern went into self-isolation after she had contact with someone who tested COVID positive on a flight to Auckland.[170] Goveror-General Cindy Kiro and chief press secretary Andrew Campbell, who were on board the same flight, also went into self-isolation.[170]

On 14 May 2022, Ardern tested positive for COVID-19.[171] Her partner Gayford had tested positive for COVID-19 several days earlier on 8 May.[172]

Foreign affairs

[change | change source]

In early December 2020, Ardern showed support for Australia during an issue between Canberra and Beijing over Chinese Foreign Ministry official Zhao Lijian's Twitter post saying that Australia had committed war crimes against Afghans.[173] She described the image as not being correct, adding that the New Zealand Government would raise its concerns with the Chinese Government.[173][174]

On 16 February 2021, Prime Minister Ardern criticised the Australian Government's decision to remove dual New Zealand–Australian national and ISIS bride Suhayra Aden's Australian citizenship.[175] Aden had migrated from New Zealand to Australia at the age of six and became an Australian citizen.[175] In response, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison defended the decision to take away Aden's citizenship, saying legislation removing dual nationals of their Australian citizenship if they were engaged in terrorist activities.[175][176][177] After a phone conversation, the two leaders agreed to work together to fix the issues Ardern had said.[178]

In response to the 2021 Israel-Palestine crisis, Ardern said on 17 May that New Zealand "condemned both the rocket fire we have seen from Hamas" and "a response that has gone well beyond self-defence on both sides".[179] She also said that Israel had the right to exist but Palestinians also had a right to a peaceful and safe home.[179]

In late May 2022, Ardern led a trade and tourism mission to the United States, where she asked President Joe Biden to have the U.S. rejoin the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.[180][181] On the trip, she made an agreement with Governor of California Gavin Newsom creating a two-way cooperation between New Zealand and California in reducing the effects of climate change and doing more research on it.[182]

In late June 2022, Ardern went to the NATO's Leader Summit.[183] This was the first time that New Zealand had formally addressed a NATO event.[183] During her speech, she talked about New Zealand's promise for peace and human rights.[183] Ardern also criticised China and Russia for human rights issues and military actions.[183][184]

Resignation

[change | change source]On 19 January 2023, Ardern announced she would resign as Labour leader and prime minister before 7 February.[13] She said the reason for her resignation was to spend more time with her family.[185] Her announcement was a surprise because a few months ago she said she would lead the Labour party into the 2023 general election.[186] In some opinion polls, Ardern's popularity had reached all-time lows in the past few months.[185]

On 22 January 2023, Chris Hipkins was elected as her replacement.[187] At Ardern's final event as Prime Minister, she said her work as the Prime Minister was the "greatest privilege" and that she loved the country and its people.[188] She officially left office on 25 January 2023 when Hipkins was sworn-in as prime minister.[14]

Popularity

[change | change source]When she became Labour Party leader, Ardern had positive coverage from the media, including international medias such as CNN,[189] with many calling it the 'Jacinda effect' and 'Jacindamania'.[190][191]

Jacindamania was seen as an important reason behind New Zealand gaining global attention and media influence in many reports.[192] In a 2018 trip, Ardern got a large amount of media attention after delivering a speech at the United Nations in New York City.[193] Many saw her as the "cure to Trumpism".[193] Many saw her as an example against masculine politicians like U.S. President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin.[194]

Ardern has been described as a celebrity politician.[195][196][197] She has become popular for her leadership following the Christchurch mosque shootings, COVID-19 pandemic and the Whakaari / White Island eruption.[198]

Ardern was one of fifteen women selected to appear on the cover of the September 2019 issue of British Vogue, by guest editor Meghan, Duchess of Sussex.[199] Forbes magazine placed her at 38 among the 100 most powerful women in the world in 2019.[200] She was included in the 2019 Time 100 list[201] and was a candidate for Time's 2019 Person of the Year.[202] Many believed that she would win the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize for her handling of the Christchurch mosque shootings.[203] In 2020, she was listed by Prospect as the second-greatest thinker for the COVID-19 era.[204] In 2021, New Zealand zoologist Steven A. Trewick named the flightless wētā species Hemiandrus jacinda in honour of Ardern.[205] A spokesperson for Ardern said that a beetle (Mecodema jacinda), a lichen, and an ant had also been named after her.[206]

In May 2021, Fortune magazine gave Ardern the top spot on their list of world’s greatest leaders, saying her leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as her handling of the Christchurch mosque shootings and the 2019 Whakaari/White Island eruption.[207][208]

Post-political career

[change | change source]On 4 April 2023, Ardern was announced as a trustee of the Earthshot Prize.[209][210] Ardern was for the position by Prince William.[211] That same day, Prime Minister Hipkins named Ardern as Special Envoy for the Christchurch Call.[212] A few weeks later, Ardern accepted dual fellowships at the Harvard Kennedy School for a semester beginning in fall 2023.[213] She also was the 2023 Angelopoulos Global Public Leaders Fellow and a Hauser Leader at the Center for Public Leadership at Harvard.[214]

In June 2023, Ardern was appointed a Dame Grand Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (GNZM), for services to the State, officially becoming Dame Jacinda Ardern.[215]

Political views

[change | change source]

Ardern has called herself as a social democrat,[11] a progressive,[12] a republican[216] and a feminist.[217] She called former Prime Minister Helen Clark, a political hero.[11][218] She believes that the large amount of child poverty and homelessness in New Zealand is a "blatant failure" of capitalism.[219][220]

Ardern believes in removing the Māori electorates and they should be decided by Māori people.[221] She supports teaching of the Māori language in schools.[11]

In September 2017, Ardern said she wanted New Zealand to have a debate on removing the monarch of New Zealand as its head of state.[216]

Ardern has supported same-sex marriage,[222] and she voted for the Marriage (Definition of Marriage) Amendment Act 2013 which legalised it.[223] In 2018, she became the first New Zealand prime minister to march in a pride parade.[224] Ardern supported legalising abortion and removing it from the Crimes Act 1961.[225][226] In March 2020, she voted for the Abortion Legislation Act that would make abortion legal.[227][228]

She described taking action on climate change as "my generation's nuclear-free moment".[229]

Ardern has also supported a two-state solution to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[106] She has criticised Israel over the death of Palestinians during protests at the Gaza border.[230]

Personal life

[change | change source]

Ardern is a second cousin of Mayor of Whanganui Hamish McDouall.[231] She is also a distant cousin of former National MP for Taranaki-King Country Shane Ardern.[232]

Ardern's partner is television presenter Clarke Gayford.[233][234] The couple first met in 2012.[235] They did not spend time together until Gayford talked to Ardern about a controversial communications bill.[233] On 3 May 2019, it was reported that Ardern was engaged to be married to Gayford.[236][237] The wedding was planned for January 2022, but she changed the wedding date for a another time because of COVID-19 restrictions.[238][239]

On 19 January 2018, Ardern announced that she was pregnant with her first child, making her New Zealand's first prime minister to be pregnant in office.[240] On 21 June 2018, she gave birth to a girl the same day,[241][242] becoming only the second elected head of government to give birth while in office (after Benazir Bhutto in 1990).[10][242] On 24 June, Ardern revealed her daughter's name as Neve Te Aroha.[243]

Though raised as a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LSD), Ardern left the church in 2005 because the church's views did not support her own political views.[244][245] In January 2017, Ardern said she was agnostic, saying "I can't see myself being a member of an organised religion again".[244] As prime minister in 2019, she met the President of LDS Church, Russell M. Nelson.[246]

References

[change | change source]- ↑ "Members Sworn". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). New Zealand Parliament. p. 2. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013.

- ↑ "Australian journalist surprised by Jacinda Ardern's accessibility". Stuff. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ↑ Election results Archived 6 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "People – New Zealand Labour Party". Archived from the original on 23 December 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kirk, Stacey (1 August 2017). "Jacinda Ardern says she can handle it and her path to the top would suggest she's right". The Dominion Post. Stuff. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ Davison, Isaac (1 August 2017). "Andrew Little quits: Jacinda Ardern is new Labour leader, Kelvin Davis is deputy". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "2017 General Election – Official Results". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Griffiths, James (19 October 2017). "Jacinda Ardern to become New Zealand Prime Minister". CNN. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ↑ "The world's youngest female leader takes over in New Zealand". The Economist. 26 October 2017. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Khan, M Ilyas (21 June 2018). "Ardern and Bhutto: Two different pregnancies in power". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

Now that New Zealand's Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has hit world headlines by becoming only the second elected head of government to give birth in office, attention has naturally been drawn to the first such leader – Pakistan's late two-time Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Murphy, Tim (1 August 2017). "What Jacinda Ardern wants". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Live: Jacinda Ardern answers NZ's questions". Stuff.co.nz. 3 August 2017. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Malpass, Luke (19 January 2023). "Live: Jacinda Ardern announces she will resign as prime minister by February 7th". Stuff. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Chris Hipkins, New Zealand's New Leader, Hopes to Put Ardern Behind Him". The New York Times. 24 January 2022.

- ↑ "Candidate profile: Jacinda Ardern". 3 News. 19 October 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Kwai, Isabella (4 September 2017). "New Zealand's Election Had Been Predictable. Then 'Jacindamania' Hit". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ↑ Gilbert, Jarrod (August 2016). "Life, kids and being Jacinda". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ↑ Cumming, Geoff (24 September 2011). "Battle for Beehive hot seat". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Bertrand, Kelly (30 June 2014). "Jacinda Ardern's country childhood". Now to Love. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ Keber, Ruth (12 June 2014). "Labour MP Jacinda Ardern warms to Hairy and friends". Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019 – via www.nzherald.co.nz.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern visits Morrinsville College". The New Zealand Herald. 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ↑ "Ardern, Jacinda: Maiden Statement". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). New Zealand Parliament. 16 December 2008. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 "Waikato BCS grad Jacinda Ardern becomes leader of the NZ Labour Party". University of Waikato. 2 August 2017. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ Cooke, Henry (16 September 2017). "How Marie Ardern got her niece Jacinda into politics". Stuff. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Ainge Roy, Eleanor (7 August 2017). "Jacinda Ardern becomes youngest New Zealand Labour leader after Andrew Little quits". Archived from the original on 12 September 2017.

- ↑ Tweed, David; Withers, Tracy (21 October 2017). "Kiwi PM Jacinda Ardern will be world's youngest female leader". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018.

- ↑ Duff, Michelle. Jacinda Ardern: The Story Behind An Extraordinary Leader. Allen & Unwin. p. 70.

- ↑ Dudding, Adam (17 August 2017). "Jacinda Ardern: I didn't want to work for Tony Blair". Stuff. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Official Count Results – Waikato". electionresults.govt.nz. 2008. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ↑ "Labour Party list for 2008 election announced | Scoop News". Scoop. 31 August 2008. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ↑ Trevett, Claire (29 January 2010). "Greens' newest MP trains his sights on the bogan vote". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Jacinda Ardern". New Zealand Parliament. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ Huffadine, Leith; Watkins, Tracy. "'Bridges and Ardern': the young guns who are now in charge". Stuff. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 "Auckland Central electorate results 2011". Electionresults.org.nz. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ↑ Miller, Raymond (2015). Democracy in New Zealand. Auckland University Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1-77558-808-5. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Official Count Results – Auckland Central". Electoral Commission. 4 October 2014. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ Small, Vernon (24 November 2014). "Little unveils new Labour caucus". Stuff. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Sachdeva, Sam (19 December 2016). "Labour MP Jacinda Ardern to run for selection in Mt Albert by-election". Stuff. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Ainge Roy, Eleanor (15 September 2017). "'I've got what it takes': will Jacinda Ardern be New Zealand's next prime minister?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern Labour's sole nominee for Mt Albert by-election". Stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ Jones, Nicholas (12 January 2017). "Jacinda Ardern to contest Mt Albert byelection". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern wins landslide victory Mt Albert by-election". The New Zealand Herald. 25 February 2017. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Mt Albert – Preliminary Count". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern confirmed as Labour's new deputy leader". 6 March 2017. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2019 – via www.nzherald.co.nz.

- ↑ "Labour's Raymond Huo set to return to Parliament after Maryan Street steps aside". The New Zealand Herald. 21 February 2017. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 "Jacinda Ardern is Labour's new leader, Kelvin Davis as deputy leader". 7 August 2017. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ↑ "Andrew Little's full statement on resignation". The New Zealand Herald. 31 July 2017. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (31 July 2017). "Jacinda Ardern becomes youngest New Zealand Labour leader after Andrew Little quits". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 "Little asked Ardern to lead six days before he resigned". The New Zealand Herald. 14 September 2017. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ↑ "Donations to Labour surge as Jacinda Ardern named new leader". The New Zealand Herald. 2 August 2017. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "Video: Jacinda Ardern won't rule out capital gains tax". Radio New Zealand. 22 August 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Tarrant, Alex (15 August 2017). "Labour leader maintains 'right and ability' to introduce capital gains tax if working group suggests it next term; Would exempt family home". Interest.co.nz. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Kirk, Stacey (1 September 2017). "Jacinda Ardern tells Kelvin Davis off over capital gains tax comments". Stuff. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Hickey, Bernard (24 September 2017). "Jacinda stumbled into a $520bn minefield". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Cooke, Henry (14 September 2017). "Election: Labour backs down on tax, will not introduce anything from working group until after 2020 election". Stuff. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "Steven Joyce still backing Labour's alleged $11.7b fiscal hole". Newshub. 19 September 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Labour leader Jacinda Ardern unshaken by Morrinsville farming protest". Newshub. 19 August 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 "Farmers protest against Jacinda Ardern's tax policies". The New Zealand Herald. 18 September 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Vowles, Jack (3 July 2018). "Surprise, surprise: the New Zealand general election of 2017". Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 13 (2): 147–160. doi:10.1080/1177083X.2018.1443472.

- ↑ "Mt Albert – Official Result". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Preliminary results for the 2017 General Election". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "'Jacindamania' fails to run wild in New Zealand poll". The Irish Times. Reuters. 23 September 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 "2017 General Election – Official Result". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Ardern and Davis to lead Labour negotiating team". Radio New Zealand. 26 September 2017. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "NZ First talks with National, Labour begin". Stuff. 5 October 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Haynes, Jessica. "Jacinda Ardern: Who is New Zealand's next prime minister?". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ Chapman, Grant. "New PM Jacinda Ardern joins an elite few among world, NZ leaders". Newshub. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "Green Party ratifies confidence and supply deal with Labour". The New Zealand Herald. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "Jacinda Ardern reveals ministers of new government". The New Zealand Herald. 26 October 2017. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "New government ministers revealed". Radio New Zealand. 25 October 2017. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ Cheng, Derek (26 October 2017). "Jacinda Ardern sworn in as new Prime Minister". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ Steafel, Eleanor (26 October 2017). "Who is New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern – the world's youngest female leader?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ↑ "Premiers and Prime Ministers". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ↑ "It's Labour! Jacinda Ardern will be next PM after Winston Peters and NZ First swing left". The New Zealand Herald. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ↑ "Members – President Of The Council Of Women World Leaders". www.lrp.lt. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ Atkinson, Neill. "Jacinda Ardern Biography". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern on baby news: 'I'll be Prime Minister and a mum'". Radio New Zealand. 19 January 2018. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ↑ Patterson, Jane (21 June 2018). "Winston Peters is in charge: His duties explained". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ↑ "Winston Peters is now officially Acting Prime Minister". The New Zealand Herald. 21 June 2018. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ "'Throw fatty out': Winston Peters fires insults on last day as PM". The New Zealand Herald. 1 August 2018. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ Mercer, Phil (16 October 2018). "A country famed for quality of life faces up to child poverty". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (2 July 2018). "Jacinda Ardern welcomes new welfare reforms from the sofa with new baby". The Guardian. Dunedin. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ↑ "Supporting New Zealand families". Beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ↑ Biddle, Donna-Lee (28 November 2019). "Free lunches for low-decile school kids: What's on the menu?". Stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Andelane, Lana (19 April 2020). "$25 benefit increase 'making a difference' for beneficiaries during lockdown – Carmel Sepuloni". Newshub. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Klar, Rebecca (6 June 2020). "New Zealand providing free sanitary products in schools". The Hill. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ↑ Molyneux, Vita (16 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Business expert condemns Government decision to raise minimum wage amid pandemic". Newshub. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Jones, Shane (23 February 2018). "Provincial Growth Fund open for business". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Jones, Nicholas (20 October 2017). "Jacinda Ardern confirms new government will dump tax cuts". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ Collins, Simon (26 June 2019). "Teachers accept pay deal – but principals reject it". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter (18 April 2019). "Week in Politics: Labour's biggest campaign burden scrapped". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ↑ Williams, Larry. "Jack Tame: No CGT is 'enormous failure' for PM". Newstalk ZB. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 93.2 Ainge-Roy, Eleanor (6 February 2018). "Jacinda Ardern defuses tensions on New Zealand's sacred Waitangi Day". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ Sachdeva, Sam (6 February 2018). "Jacinda Ardern ends five-day stay in Waitangi". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Manhire, Toby (11 September 2019). "Timeline: Everything we know about the Labour staffer inquiry". The Spinoff. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ↑ Vance, Andrea. "Labour Party president Nigel Haworth has resigned – but it's not over". Stuff. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

Ardern says she didn't know the allegations were sexual until this week. That's hard to swallow.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (12 September 2019). "Ardern under pressure as staffer accused of sexual assault quits". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ↑ "New Zealand sets 2020 cannabis referendum". BBC News. 18 December 2018. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Cave, Damien (1 October 2020). "Jacinda Ardern Admits Having Used Cannabis. New Zealanders Shrug: 'Us Too.'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ↑ Rychert, Marta; Wilkins, Chris (7 March 2021). "Why did New Zealand's referendum to legalise recreational cannabis fail?". Drug and Alcohol Review. 40 (6): 877–881. doi:10.1111/dar.13254. PMID 33677836. S2CID 232140948.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Walters, Laura; Small, Vernon. "Jacinda Ardern makes first state visit to Australia to strengthen ties". Stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ Trevett, Claire (5 November 2017). "Key bromance haunts Jacinda Ardern's first Australia visit". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ "TPP deal revived once more, 20 provisions suspended". Radio New Zealand. 12 November 2017. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ↑ "Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership" (PDF). New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ↑ Satherley, Dan (12 November 2017). "TPP 'a damned sight better' now – Ardern". Newshub.co.nz. Archived from the original on 19 May 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 "NZ won't be bullied on Israel vote – Ardern". Radio New Zealand. 21 December 2017. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (24 September 2018). "Jacinda Ardern makes history with baby Neve at UN general assembly". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ↑ Cole, Brendan. "Jacinda Ardern: New Zealand Prime Minister Makes History By Becoming First Woman to Bring Baby into U.N.Assembly". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ↑ "Full speech: 'Me too must become we too' – Jacinda Ardern calls for gender equality, kindness at UN". TVNZ. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ Coughlan, Thomas (30 October 2018). "Ardern softly raises concern over Uighurs". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Christian, Harrison (7 November 2018). "The disappearing people: Uighur Kiwis lose contact with family members in China". Stuff. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Mutch Mckay, Jessica (14 November 2018). "Jacinda Ardern meets with Myanmar's leader, voices concern on Rohingya situation". TVNZ. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Small, Zane (15 November 2018). "Jacinda Ardern offers NZ's help to resolve Myanmar's Rohingya crisis". Newshub. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 Ensor, Jamie; Lynch, Jenna (24 September 2019). "Jacinda Ardern, Donald Trump meeting: US President takes interest in gun buyback". Newshub. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ↑ Gambino, Lauren (23 September 2019). "Trump showed interest in New Zealand gun buyback program, Ardern says". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern: Australia's deportation policy 'corrosive'". BBC News. 28 February 2020. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern blasts Scott Morrison over Australia's deportation policy – video". The Guardian. Australian Associated Press. 28 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ↑ Cooke, Henry (28 February 2020). "Extraordinary scene as Jacinda Ardern directly confronts Scott Morrison over deportations". Stuff. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ↑ Wahlquist, Calla (24 March 2019). "An image of hope: how a Christchurch photographer captured the famous Ardern picture". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ↑ McConnell, Glenn (18 March 2019). "Face of empathy: Jacinda Ardern photo resonates worldwide after attack". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 "Three in custody after 49 killed in Christchurch mosque shootings". Stuff. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ Britton, Bianca (15 March 2019). "New Zealand PM full speech: 'This can only be described as a terrorist attack'". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ Greenfield, Charlotte; Westbrook, Tom. "New gun laws to make NZ safer after mosque shootings, says PM Ardern". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ George, Steve; Berlinger, Joshua; Whiteman, Hilary; Kaur, Harmeet; Westcott, Ben; Wagner, Meg (19 March 2019). "New Zealand mosque terror attacks". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ↑ "Christchurch shootings: Ardern vows never to say gunman's name". BBC News. 19 March 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ Collman, Ashley (19 March 2019). "People around the world are praising New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern for her compassionate response to the Christchurch mosque shootings". Thisisinsider. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ Newson, Rhonwyn (18 March 2019). "Christchurch terror attack: Jacinda Ardern praised for being 'compassionate leader'". Newshub. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ "New Zealand's prime minister receives worldwide praise for her response to the mosque shootings". The Washington Post. 19 March 2019. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ Shad, Saman (20 March 2019). "Five ways Jacinda Ardern has proved her leadership mettle". SBS News. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ↑ Picheta, Rob. "Image of Jacinda Ardern projected onto world's tallest building". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ↑ Prior, Ryan. "A painter has revealed an 80-foot mural of New Zealand's prime minister comforting woman after mosque attacks". CNN. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ↑ Walls, Jason (16 March 2019). "Christchurch mosque shootings: New Zealand to ban semi-automatic weapons". nzherald.co.nz. The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (19 March 2019). "Jacinda Ardern says cabinet agrees New Zealand gun reform 'in principle'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ↑ Graham-McLay, Charlotte (10 April 2019). "New Zealand Passes Law Banning Most Semiautomatic Weapons, Weeks After Massacre". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 "Core group of world leaders to attend Jacinda Ardern-led Paris summit". The New Zealand Herald. 29 April 2019. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ↑ Baker, Michael G.; Wilson, Nick; Anglemyer, Andrew (7 August 2020). "Successful Elimination of Covid-19 Transmission in New Zealand". New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (8). NEJM.org: e56. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2025203. PMC 7449141. PMID 32767891.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 "Everyone travelling to NZ from overseas to self-isolate". Radio New Zealand. 14 March 2020. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ↑ Keogh, Brittany (14 March 2020). "Coronavirus: Prime Minister Ardern updates New Zealand on Covid-19 outbreak". Stuff. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ↑ Whyte, Anna (19 March 2020). "PM places border ban on all non-citizens and non-permanent residents entering NZ". TVNZ. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ↑ "Live: PM Jacinda Ardern to give update on coronavirus alert level". Stuff. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ↑ Ensor, Jamie (24 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Jacinda Ardern's 'incredible', 'down to earth' leadership praised after viral video". Newshub. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Khalil, Shaimaa (22 April 2020). "Coronavirus: How New Zealand relied on science and empathy". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Fifield, Anna (7 April 2020). "New Zealand isn't just flattening the curve. It's squashing it". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Boyle, Chelseas (23 April 2020). "Lockdown lawsuit fails: Legal action against Jacinda Ardern dismissed". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Earley, Melanie (23 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Man's lawsuit over Covid-19 lockdown restrictions dismissed". Stuff. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ "Trans-Tasman bubble: Jacinda Ardern gives details of Australian Cabinet meeting". Radio New Zealand. 5 May 2020. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Wescott, Ben (5 May 2020). "Australia and New Zealand pledge to introduce travel corridor in rare coronavirus meeting". CNN. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ O'Brien, Tova (18 May 2020). "Newshub-Reid Research Poll: Jacinda Ardern goes stratospheric, Simon Bridges is annihilated". Newshub. MediaWorks TV. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ↑ "Pressure mounts as National falls to 29%, Labour skyrockets in 1 NEWS Colmar Brunton poll". 1 News. TVNZ. 21 May 2020. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ↑ Pandey, Swati (18 May 2020). "Ardern becomes New Zealand's most popular PM in a century – poll". Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020 – via Reuters.

- ↑ O'Brien, Tova (18 May 2020). "Newshub-Reid Research Poll: Simon Bridges still confident he will lead National into election despite personal poll rating below 5 percent". Newshub. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ↑ "New Zealand election: Jacinda Ardern's Labour Party scores landslide win". BBC News. 17 October 2020. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ↑ "2020 General Election and Referendums – Official Result". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ "Mt Albert – Official Result". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Election 2020: The big winners and losers in Auckland". Stuff. 17 October 2020. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ↑ "New Zealand's Ardern credits virus response for election win". The Independent. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ↑ 157.0 157.1 157.2 Taylor, Phil (2 December 2020). "New Zealand declares a climate change emergency". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ Cooke, Henry (2 December 2020). "Government will have to buy electric cars and build green buildings as it declares climate change emergency". Stuff. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ Sam Sachdeva (23 March 2021). "'No silver bullet', but Govt fires plenty at housing crisis". Newsroom. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ Jeremy Couchman (25 March 2021). "Higher house price caps would have helped only a few hundred first home buyers". Newsroom. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ Neilson, Michael (14 June 2021). "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announces apology for dawn raids targeting Pasifika". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ↑ Whyte, Anna (14 June 2021). "Government Minister Aupito William Sio in tears as he recalls family being subjected to dawn raid". 1 News. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ↑ "New Zealand apologises for 1970s 'Dawn Raids'". Al Jazeera. 1 August 2021. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ↑ 164.0 164.1 "Covid 19 coronavirus: Cook Islands, New Zealand travel bubble without quarantine from early next year". The New Zealand Herald. 12 December 2020. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ Galloway, Anthony (14 December 2020). "New Zealand travel bubble with Australia coming in early 2021, NZ PM confirms". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 14 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ↑ "Govt secures another two Covid-19 vaccines, PM says every New Zealander will be able to be vaccinated". Radio New Zealand. 16 December 2020. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ↑ de Jong, Eleanor (26 January 2021). "New Zealand borders to stay closed until citizens are 'vaccinated and protected'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ↑ "Covid 19 coronavirus: No new community cases - Ashley Bloomfield and health officials give press conference as first Kiwis receive vaccinations". NZ Herald. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ↑ "New Zealand enters nationwide lockdown over one Covid case". BBC News. 17 August 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ↑ 170.0 170.1 "Covid-19: Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern in self-isolation, identified as close contact of Covid case". Stuff. 29 January 2022. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ↑ "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern tests positive for Covid-19". Radio New Zealand. 14 May 2022. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ↑ Cooke, Henry (8 May 2022). "Covid-19 NZ: Jacinda Ardern isolating at home as partner Clarke Gayford infected". Stuff. Archived from the original on 8 May 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ↑ 173.0 173.1 Perry, Nick (2 December 2020). "New Zealand joins Australia in denouncing China's tweet". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ Patterson, Jane (1 December 2020). "New Zealand registers concern with China over official's 'unfactual' tweet". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ 175.0 175.1 175.2 Welch, Dylan; Dredge, Suzanne; Dziedzic, Stephen (16 February 2021). "New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern criticises Australia for stripping dual national terror suspect's citizenship". ABC News. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ↑ Whyte, Anna (16 February 2021). "Jacinda Ardern delivers extraordinary broadside at Australia over woman detained in Turkey – 'Abdicated its responsibilities'". 1 News. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ↑ "Ardern condemns Australia for revoking ISIL suspect's citizenship". Al Jazeera. 16 February 2021. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ↑ Manch, Thomas (17 February 2021). "Jacinda Ardern, Scott Morrison agree to work in 'spirit of our relationship' over alleged Isis terrorist". Stuff. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ↑ 179.0 179.1 "'I despair at what's happening' — Ardern condemns both Israel and Hamas over deadly violence in Gaza". 1 News. 17 May 2021. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ↑ Burns-Francis, Anna (25 May 2022). "Jacinda Ardern busy promoting NZ on US visit". 1 News. TVNZ. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ "New Zealand's Ardern urges US to return to regional trade pact". Al Jazeera. 26 May 2022. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ "New Zealand signs partnership with California on climate change". Radio New Zealand. 28 May 2022. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ 183.0 183.1 183.2 183.3 McClure, Tess (30 June 2022). "West must stand firm as China challenges 'rules and norms', Ardern tells Nato". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ↑ McConnell, Glenn (30 June 2022). "Jacinda Ardern calls for nuclear disarmament, criticises China over human rights during Nato speech". Stuff. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ↑ 185.0 185.1 "Jacinda Ardern: New Zealand PM to step down next month". BBC News. 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ↑ McClure, Tess (7 November 2022). "Jacinda Ardern rallies party faithful as Labour faces difficult re-election path". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ↑ "Chris Hipkins on flight when he received leadership backing". 1 News. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ↑ "Leading New Zealand was 'greatest privilege', says Jacinda Ardern at final event". The Guardian. 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ↑ Griffiths, James (1 September 2017). "'All bets are off' in New Zealand vote as 'Jacindamania' boosts Labour". CNN. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ↑ Peacock, Colin (3 August 2017). "'Jacinda effect' in full effect in the media". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (10 August 2017). "New Zealand gripped by 'Jacindamania' as new Labour leader soars in polls". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ↑ Bateman, Sophie (16 July 2018). "Jacindamania helped NZ's global influence, index reveals". Newshub. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ↑ 193.0 193.1 Peacock, Colin (30 September 2018). "Jacindamania goes global: the PM in US at the UN". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ Watkins, Tracy (24 September 2018). "What lies behind Jacinda Ardern's appeal in the US? To her followers, it's hope". Stuff. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ Bala, Thenappan (16 March 2019). "Jacinda Ardern: The Celebrity". Penn Political Review. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ Hehir, Liam (6 May 2019). "The growth of celebrity politics should be resisted". Stuff. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ↑ Kapitan, Sommer (4 September 2020). "The Facebook prime minister: how Jacinda Ardern became New Zealand's most successful political influencer". The Conversation. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ↑ Manhire, Toby (11 December 2019). "The decade in politics: From Team Key to Jacindamania". The Spinoff. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ↑ "Meghan Markle puts Sinéad Burke on the cover of Vogue's September issue". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern". Forbes. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ↑ Khan, Sadiq (2019). "Jacinda Ardern". Time. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ↑ Stump, Scott (9 December 2019). "Who will be TIME's 2019 Person of the Year? See the shortlist". Today. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ↑ Bunyan, Rachael. "Here Are the Favorites to Win the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize". Time. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ↑ "The world's top 50 thinkers for the Covid-19 age" (PDF). Prospect. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ↑ Trewick, Steven A. (12 March 2021). "A new species of large Hemiandrus ground wētā (Orthoptera: Anostostomatidae) from North Island, New Zealand". Zootaxa. 4942 (2): 207–218. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4942.2.4. PMID 33757066. S2CID 232337351.

- ↑ Hunt, Elle (12 March 2021). "Hemiandrus jacinda: insect named after New Zealand prime minister". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern". Fortune. 14 May 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ Forrester, Georgina (14 May 2021). "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern tops Fortune magazine's world greatest leaders list". Stuff. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ tom_tep (4 April 2023). "Jacinda Ardern joins The Earthshot Prize as a Trustee". The Earthshot Prize. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ↑ Wood, Patrick (6 April 2023). "New Zealand's Jacinda Ardern takes on a new role after leaving politics this week". NPR. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ↑ Adams, Charley (4 April 2023). "Jacinda Ardern appointed trustee of Prince William's Earthshot Prize". BBC News. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ↑ "Former PM Jacinda Ardern appointed as Christchurch Call Envoy". Radio New Zealand. 4 April 2023. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ↑ McClure, Tess (25 April 2023). "Jacinda Ardern takes up leadership and online extremism roles at Harvard". The Guardian.

- ↑ LeBlanc, Steve (25 April 2023). "Ex-New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern to join Harvard". Associated Press.

- ↑ "The King's Birthday and Coronation honours list 2023". Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ↑ 216.0 216.1 Lagan, Bernard (7 September 2017). "Jacinda Ardern, New Zealand's contender for PM, says: let's lose the Queen". The Times. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ↑ Ardern, Jacinda (20 May 2015). "Jacinda Ardern: I am a feminist". Villainesse. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ "Ardern confirmed as new Labour leader". Otago Daily Times. 1 August 2017. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ Satherley, Dan; Owen, Lisa (21 October 2017). "Homelessness proves capitalism is a 'blatant failure' – Jacinda Ardern". Newshub. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

Asked directly if capitalism had failed low-income Kiwis, Ms. Ardern was unequivocal."If you have hundreds of thousands of children living in homes without enough to survive, that's a blatant failure. What else could you describe it as? [. . .] It all comes down to whether or not you recognize where the market has failed and where intervention is required. Has it failed our people in recent times? Yes.

- ↑ Baynes, Chris (1 April 2019). "New Zealand's new prime minister calls capitalism a 'blatant failure'". The Independent. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ↑ "Labour's leadership duo talk tax, Maori prisons and who'll be deputy leader in a coalition". Stuff. 5 August 2017. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ "Broadsides: Do you support same-sex marriage?". The New Zealand Herald. 22 June 2011. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ↑ "Marriage equality bill: How MPs voted". Waikato Times. 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (17 February 2018). "Jacinda Ardern becomes first New Zealand PM to march in gay pride parade". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ↑ Miller, Corazon (11 September 2017). "Labour leader Jacinda Ardern tackles 'smear campaign' on abortion stance". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "English, Little, Ardern on abortion laws". Your NZ. 13 March 2017. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ↑ "Parliament removes abortion from Crimes Act". The Beehive. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ↑ "Abortion Legislation Bill passes third and final reading in Parliament". Radio New Zealand. 18 March 2020. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ↑ Trevett, Claire (20 August 2017). "Jacinda Ardern's rallying cry: Climate change the nuclear-free moment of her generation". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ↑ Trevett, Claire (15 May 2018). "PM Jacinda Ardern: Gaza deaths show US Embassy move to Jerusalem hurt chance of peace". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Manhire, Toby (19 September 2017). "'My final, final plea': a day in Whanganui with Jacinda Ardern". The Spinoff. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ↑ "Things we learned about Jacinda Ardern". Newshub. 6 November 2014. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ↑ 233.0 233.1 Knight, Kim (16 July 2016). "Clarke Gayford: Jacinda Ardern is the best thing that's ever happened to me". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 17 July 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ "Clarke Gayford". NZ On Screen. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern was on a date with another man when she first met Clarke Gayford". Stuff. 1 May 2018. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ↑ "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern engaged to partner Clarke Gayford". Radio New Zealand. 3 May 2019. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ↑ "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and Clarke Gayford engaged". The New Zealand Herald. 3 May 2019. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ↑ "Covid 19 Omicron outbreak: PM Jacinda Ardern cancels wedding as country moves to red". The New Zealand Herald. 23 January 2022.

- ↑ "'Such is life': NZ PM calls off wedding". BBC News. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ↑ "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announces pregnancy". The New Zealand Herald. 19 January 2018. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ↑ "Live: Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern's baby is on the way". Stuff. 21 June 2018. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ 242.0 242.1 "It's a girl! Jacinda Ardern gives birth to her first child". Newshub. 21 June 2018. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

She is only the second world leader in history to give birth while in office. Former Prime Minister of Pakistan Benazir Bhutto gave birth to a baby girl in 1990.

- ↑ "Watch: PM Jacinda Ardern leaves hospital with 'Neve Te Aroha'". Radio New Zealand. 24 June 2018. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ↑ 244.0 244.1 Knight, Kim (29 January 2017). "The politics of life: The truth about Jacinda Ardern". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ Park, Benjamin (14 November 2018). "Commentary: What the two 'Mormon' senators tell us about the LDS battle over sexuality". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ↑ "President Nelson Meets with New Zealand Prime Minister". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

Other websites

[change | change source]- Jacinda Ardern's Archived 2017-08-02 at the Wayback Machine profile on the New Zealand Parliament website

- Jacinda Ardern at the New Zealand Labour Party