Abstract

Platelets are the second most abundant cell type in blood and are essential for maintaining haemostasis. Their count and volume are tightly controlled within narrow physiological ranges, but there is only limited understanding of the molecular processes controlling both traits. Here we carried out a high-powered meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in up to 66,867 individuals of European ancestry, followed by extensive biological and functional assessment. We identified 68 genomic loci reliably associated with platelet count and volume mapping to established and putative novel regulators of megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. These genes show megakaryocyte-specific gene expression patterns and extensive network connectivity. Using gene silencing in Danio rerio and Drosophila melanogaster, we identified 11 of the genes as novel regulators of blood cell formation. Taken together, our findings advance understanding of novel gene functions controlling fate-determining events during megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation, providing a new example of successful translation of GWAS to function.

To discover novel genetic determinants of megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation, we performed meta-analyses of GWAS for mean platelet volume (MPV) and platelet count (PLT). Our analyses included 18,600 (13 studies, MPV) and 48,666 (23 studies, PLT) individuals of European descent, respectively, and up to ~2.5 million genotyped or imputed single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)1. Briefly, we tested within each study (Supplementary Table 1) the associations of MPV and PLT with each SNP using an additive model; we then combined these study-specific test statistics in a fixed-effects meta-analysis. To reduce the risk of spurious associations, we applied common stringent quality control filters and the genomic control method2 to the meta-analysis, which shows no evidence for residual inflation of summary statistics (Supplementary Fig. 1).

A total of 52 genomic loci reaching statistical significance at the genome-wide adjusted threshold of P ≤ 5 × 10−8 were discovered in this stage 1 analysis; 55 additional loci reached suggestive association (5 × 10−8 < P ≤ 5 × 10−6). We tested one SNP per locus in a stage 2 analysis that included in silico and de novo replication data in up to 18,838 individuals from 12 additional studies, confirming 15 additional loci (Supplementary Table 2). One further independent locus (TRIM58) associated with PLT was identified through detection of secondary association signals. Overall, 68 independent genomic regions were associated with PLT and MPV with P ≤ 5 × 10−8, of which 52 are new and 16 were described previously in Europeans3-6 (Table 1). Of the 68 loci, 43 and 25 loci were associated significantly with PLT and MPV, respectively; 16 of them reached genome-wide significance with both traits (Supplementary Fig. 2). This partial overlap reflects the negative correlation of both traits (gender-adjusted r = −0.49, Fig. 1a) that results from the tight control of platelet mass (PLT × MPV)7. The association of some loci with both PLT and MPV may reflect this negative correlation between the two traits or independent pleiotropic effects of a locus on megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. The different statistical power at the two traits and small effect sizes at many loci reduce our power to discriminate among loci controlling MPV and PLT through analysis of platelet mass. Their testing will require the collection and analysis of PLT and MPV in large independent homogeneous cohorts. Some loci, however, have a clear-cut effect. For instance, BAK1 affects PLT specifically, compatible with its role in apoptosis and platelet lifespan.

Table 1. Summary of loci associated with platelet count and mean platelet volume in Europeans.

| GWAS locus |

Trait | Sentinel SNP | Chr (build 36) |

Position (build 36) |

Cytoband | Locus | Effect/other allele* |

n | Effect (s.e.)† | P value‡ | Het. P value |

Rep.¶ | Refs# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MPV | rs17396340 | 1 | 10,208,762 | 1p36.22 | KIF1B | A/G | 21,612 | 0.008 (0.002) | 2.83 × 10−8 | 0.83 | – | – |

| 2 | PLT | rs2336384 | 1 | 11,968,649 | 1p36.22 | MFN2 | G/T | 57,366 | 2.172 (0.382) | 1.25 × 10−8 | 0.31 | – | – |

| 3 | MPV | rs10914144 | 1 | 170,216,372 | 1q24.3 | DNM3 | C/T | 18,589 | 0.014 (0.001) | 1.11 × 10−24 | 0.46 | Yes | 6 |

| PLT | rs10914144 | 1 | 170,216,372 | T/C | 54,978 | 3.417 (0.487) | 2.22 × 10−12 | 0.79 | Yes | ||||

| 4 | MPV | rs1172130 | 1 | 203,511,575 | 1q32.1 | TMCC2 | G/A | 21,141 | 0.011 (0.001) | 3.82 × 10−27 | 0.17 | Yes | 6 |

| PLT | rs1668871 | 1 | 203,503,759 | C/T | 58,108 | 2.804 (0.368) | 2.59 × 10−14 | 0.45 | – | ||||

| 5 | PLT | rs7550918 | 1 | 245,742,181 | 1q44 | LOC148824 | T/C | 54,171 | 3.133 (0.471) | 2.91 × 10−11 | 0.85 | – | – |

| 6 | PLT | rs3811444 | 1 | 246,106,073 | 1q44 | TRIM581 | C/T | 27,955 | 3.346 (0.574) | 5.60 × 10−9 | 0.66 | – | – |

| 7 | PLT | rs1260326 | 2 | 27,584,443 | 2p23 | GCKR | T/C | 54,396 | 2.334 (0.381) | 9.12 × 10−10 | 0.11 | Yes | – |

| 8 | MPV | rs649729 | 2 | 31,317,888 | 2p23.1 | EHD3 | T/A | 20,850 | 0.008 (0.001) | 1.17 × 10−12 | 0.61 | Yes | 6 |

| PLT | rs625132 | 2 | 31,335,803 | G/A | 45,217 | 4.236 (0.568) | 9.15 × 10−14 | 0.98 | – | ||||

| 9 | PLT | rs17030845 | 2 | 43,541,382 | 2p21 | THADA | C/T | 65,738 | 3.577 (0.556) | 1.27 × 10−10 | 0.40 | – | – |

| 10 | MPV | rs4305276 | 2 | 241,143,685 | 2q37.3 | ANKMY1 | G/C | 20,618 | 0.008 (0.001) | 1.71 × 10−11 | 0.71 | – | – |

| 11 | PLT | rs7616006 | 3 | 12,242,647 | 3p25 | SYN2 | A/G | 58,564 | 1.997 (0.366) | 4.86 × 10−8 | 0.20 | – | – |

| 12 | PLT | rs7641175 | 3 | 18,286,415 | 3p23 | SATB1 | A/G | 58,366 | 2.757 (0.416) | 3.37 × 10−11 | 0.34 | – | – |

| 13 | MPV | rs1354034 | 3 | 56,824,788 | 3p14.3 | ARHGEF3 | T/C | 18,286 | 0.023 (0.001) | 3.31 × 10−69 | 0.00 | Yes | 4,6 |

| PLT | rs1354034 | 3 | 56,824,788 | C/T | 49,135 | 6.848 (0.442) | 2.86 × 10−54 | 0.50 | Yes | ||||

| 14 | PLT | rs3792366 | 3 | 124,322,565 | 3q21.1 | PDIA5 | G/A | 58,335 | 2.153 (0.365) | 3.60 × 10−9 | 0.07 | – | – |

| 15 | MPV | rs10512627 | 3 | 125,822,911 | 3q21.1 | KALRN | C/G | 21,108 | 0.006 (0.001) | 5.10 × 10−10 | 0.41 | – | – |

| 16 | MPV | rs11734132 | 4 | 6,942,419 | 4p16.1 | KIAA0232 | G/C | 17,444 | 0.011 (0.002) | 1.11 × 10−11 | 0.20 | – | – |

| 17 | PLT | rs7694379 | 4 | 88,405,532 | 4q22.1 | HSD17B13 | A/G | 56,430 | 2.129 (0.37) | 8.70 × 10−9 | 0.44 | Yes | – |

| 18 | MPV | rs2227831 | 5 | 76,059,249 | 5q13.3 | F2R | G/A | 21,654 | 0.021 (0.003) | 9.65 × 10−16 | 0.11 | – | – |

| PLT | rs17568628 | 5 | 76,082,694 | T/C | 44,759 | 6.074 (0.993) | 9.61 × 10−10 | 0.77 | – | ||||

| 19 | PLT | rs700585 | 5 | 88,187,872 | 5q14.3 | MEF2C | C/T | 55,469 | 2.703 (0.442) | 9.86 × 10−10 | 0.06 | – | – |

| MPV | rs4521516 | 5 | 88,135,706 | G/C | 28,157 | 0.008 (0.001) | 1.89 × 10−9 | 0.39 | – | ||||

| 20 | PLT | rs2070729 | 5 | 131,847,819 | 5q31.1 | IRF1 | A/C | 56,469 | 2.394 (0.371) | 1.13 × 10−10 | 0.73 | – | – |

| 21 | MPV | rs10076782 | 5 | 158,537,540 | 5q33.3 | RNF145 | A/G | 18,025 | 0.007 (0.001) | 4.48 × 10−8 | 0.52 | – | – |

| 22 | PLT | rs441460 | 6 | 25,656,266 | 6p22.2 | LRRC16 | G/A | 58,064 | 3.08 (0.359) | 8.70 × 10−18 | 0.61 | – | – |

| 23 | PLT | rs3819299 | 6 | 31,430,345 | 6p21.33 | HLA-B | G/T | 48,687 | 5.048 (0.824) | 8.80 × 10−10 | 0.90 | – | – |

| 24 | PLT | rs399604 | 6 | 33,082,991 | 6p21.32 | HLA-DOA | C/T | 57,674 | 2.346 (0.365) | 1.30 × 10−10 | 0.23 | – | – |

| 25 | PLT | rs210134 | 6 | 33,648,186 | 6p21.31 | BAK1 | G/A | 58,554 | 4.957 (0.396) | 7.11 × 10−36 | 0.67 | Yes | 6,8 |

| 26 | PLT | rs9399137 | 6 | 135,460,710 | 6q23.3 | HBS1L–MYB | C/T | 57,857 | 5.901 (0.41) | 5.04 × 10−47 | 0.74 | Yes | 8 |

| 27 | MPV | rs342293 | 7 | 106,159,454 | 7q22.3 | FLJ36031– PIK3CG |

G/C | 20,193 | 0.017 (0.001) | 7.03 × 10−57 | 0.19 | Yes | 5,6 |

| PLT | rs342275 | 7 | 106,146,451 | C/T | 58,571 | 3.742 (0.363) | 5.57 × 10−25 | 0.17 | – | ||||

| 28 | PLT | rs4731120 | 7 | 123,198,458 | 7q31.3 | WASL | C/A | 66,147 | 4.14 (0.592) | 2.77 × 10−12 | 0.46 | – | – |

| 29 | PLT | rs6993770 | 8 | 106,650,703 | 8q23.1 | ZFPM2 | A/T | 54,960 | 3.668 (0.437) | 4.30 × 10−17 | 0.14 | – | – |

| 30 | PLT | rs6995402 | 8 | 145,077,548 | 8q24.3 | PLEC1 | C/T | 57,593 | 2.304 (0.371) | 5.09 × 10−10 | 0.10 | – | – |

| 31 | MPV | rs10813766 | 9 | 321,489 | 9p24.3 | DOCK8 | T/G | 21,104 | 0.007 (0.001) | 3.68 × 10−12 | 0.45 | – | – |

| 32 | PLT | rs409801 | 9 | 4,734,742 | 9p24.1 | AK3 | C/T | 56,063 | 5.585 (0.378) | 2.59 × 10−49 | 0.47 | – | 6 |

| 33 | PLT | rs13300663 | 9 | 4,804,947 | 9p24.1 | RCL1 | C/G | 48,092 | 5.585 (0.483) | 9.83 × 10−30 | 0.64 | Yes | 8 |

| 34 | PLT | rs3731211 | 9 | 21,976,846 | 9p21.3 | CDKN2A | A/T | 54,529 | 3.281 (0.438) | 6.43 × 10−14 | 0.86 | Yes | – |

| 35 | PLT | rs11789898 | 9 | 135,915,483 | 9q34.2 | BRD3 | T/G | 57,391 | 3.014 (0.476) | 2.39 × 10−10 | 0.70 | – | – |

| 36 | MPV | rs7075195 | 10 | 64,720,664 | 10q21.2 | JMJD1C | A/G | 21,226 | 0.014 (0.001) | 2.39 × 10−44 | 0.89 | Yes | 6 |

| PLT | rs10761731 | 10 | 64,697,615 | T/A | 54,344 | 3.849 (0.378) | 2.02 × 10−24 | 0.56 | Yes | ||||

| 37 | PLT | rs505404 | 11 | 233,267 | 11p15.5 |

PSMD13

–

NLRP6 |

G/T | 54,642 | 4.662 (0.453) | 7.44 × 10−25 | 0.86 | – | 6 |

| MPV | rs17655730 | 11 | 260,714 | T/C | 20,875 | 0.01 (0.001) | 2.29 × 10−15 | 0.29 | – | ||||

| 38 | PLT | rs4246215 | 11 | 61,320,874 | 11q12.2 | FEN1 | T/G | 56,299 | 2.451 (0.39) | 3.31 × 10−10 | 0.41 | Yes | – |

| 39 | PLT | rs4938642 | 11 | 118,605,115 | 11q23.3 | CBL | C/G | 56,605 | 4.73 (0.727) | 7.66 × 10−11 | 0.98 | Yes | – |

| 40 | MPV | rs1558324 | 12 | 6,159,479 | 12p13.31 | CD9–VWF | A/G | 20,387 | 0.01 (0.001) | 1.55 × 10−21 | 0.48 | Yes | – |

| PLT | rs7342306 | 12 | 6,161,353 | G/A | 55,636 | 2.532 (0.384) | 4.29 × 10−11 | 0.14 | – | ||||

| 41 | MPV | rs2015599 | 12 | 29,326,746 | 12p11.22 | MLSTD1 | A/G | 21,102 | 0.008 (0.001) | 5.55 × 10−16 | 0.76 | – | – |

| 42 | MPV | rs10876550 | 12 | 52,998,574 | 12q13.13 |

COPZ1

–

NFE2–CBX5 |

G/A | 21,214 | 0.008 (0.001) | 1.86 × 10−14 | 0.38 | Yes | – |

| 43 | MPV | rs2950390 | 12 | 55,341,557 | 12q13.3 |

PTGES3

–

BAZ2A |

C/T | 21,238 | 0.008 (0.001) | 7.45 × 10−14 | 0.75 | – | – |

| PLT | rs941207 | 12 | 55,309,550 | G/C | 55,653 | 2.751 (0.431) | 1.74 × 10−10 | 0.33 | – | ||||

| 44 | PLT | rs3184504 | 12 | 110,368,990 | 12q24.12 | SH2B3 | T/C | 56,354 | 3.99 (0.374) | 1.22 × 10−26 | 0.07 | – | 6,8 |

| 45 | PLT | rs17824620 | 12 | 111,585,376 | 12q24.13 |

RPH3A

–

PTPN11 |

C/A | 51,530 | 2.457 (0.428) | 9.67 × 10−9 | 0.26 | – | – |

| 46 | MPV | rs7961894 | 12 | 120,849,965 | 12q24.31 | WDR66 | T/C | 29,755 | 0.03 (0.001) | 1.42 × 10−103 | 0.48 | Yes | 4,6 |

| PLT | rs7961894 | 12 | 120,849,965 | C/T | 51,897 | 3.923 (0.609) | 1.22 × 10−10 | 0.05 | Yes | ||||

| 47 | PLT | rs4148441 | 13 | 94,696,207 | 13q32 | ABCC4 | G/A | 64,120 | 4.117 (0.6) | 6.76 × 10−12 | 0.38 | Yes | – |

| 48 | MPV | rs7317038 | 13 | 113,060,898 | 13q34 | GRTP1 | C/T | 27,646 | 0.006 (0.001) | 8.27 × 10−12 | 0.09 | – | – |

| 49 | PLT | rs8022206 | 14 | 67,590,658 | 14q24.1 | RAD51L1 | G/A | 52,251 | 3.197 (0.5) | 1.55 × 10−10 | 0.59 | – | – |

| 50 | PLT | rs8006385 | 14 | 92,570,778 | 14q31 | ITPK1 | G/A | 64,929 | 3.587 (0.558) | 1.24 × 10−10 | 0.28 | – | – |

| 51 | PLT | rs7149242 | 14 | 100,229,168 | 14q32.2 |

C14orf70

–

DLK1 |

G/T | 61,247 | 2.142 (0.385) | 2.68 × 10−8 | 0.07 | – | – |

| 52 | PLT | rs11628318 | 14 | 102,109,839 | 14q32.31 | RCOR1 | A/T | 62,438 | 2.572 (0.405) | 2.04 × 10−10 | 0.84 | – | – |

| 53 | PLT | rs2297067 | 14 | 102,636,537 | 14q32.32 | C14orf73 | T/C | 41,687 | 3.538 (0.553) | 1.58 × 10−10 | 0.79 | – | – |

| MPV | rs944002 | 14 | 102,642,567 | A/G | 22,910 | 0.008 (0.001) | 4.76 × 10−11 | 0.66 | Yes | ||||

| 54 | MPV | rs3000073 | 14 | 104,800,836 | 14q32.33 | BRF1 | G/A | 21,229 | 0.007 (0.001) | 3.27 × 10−11 | 0.28 | – | – |

| 55 | PLT | rs3809566 | 15 | 61,120,776 | 15q22.2 | TPM1 | G/A | 57,113 | 2.443 (0.39) | 3.65 × 10−10 | 0.33 | – | 6 |

| 56 | PLT | rs1719271 | 15 | 62,970,853 | 15q22.31 | ANKDD1A | G/A | 56,782 | 3.414 (0.502) | 1.05 × 10−11 | 0.00 | – | – |

| 57 | PLT | rs6065 | 17 | 4,777,160 | 17pter-p12 | GP1BA | T/C | 64,987 | 4.191 (0.63) | 2.92 × 10−11 | 0.00 | Yes | 8 |

| 58 | PLT | rs397969 | 17 | 19,744,838 | 17p11.1 | AKAP10 | C/T | 60,944 | 2.131 (0.357) | 2.32 × 10−9 | 0.92 | – | – |

| 59 | MPV | rs8076739 | 17 | 24,738,712 | 17q11.2 | TAOK1 | T/C | 21,652 | 0.013 (0.001) | 4.59 × 10−38 | 0.12 | – | 4,6 |

| PLT | rs559972 | 17 | 24,838,621 | T/C | 53,460 | 3.264 (0.375) | 3.30 × 10−218 | 0.25 | |||||

| 60 | PLT | rs10512472 | 17 | 30,908,916 | 17q12 |

SNORD7

–

AP2B1 |

C/T | 58,692 | 3.636 (0.477) | 2.40 × 10−14 | 0.08 | Yes | – |

| MPV | rs16971217 | 17 | 30,968,167 | C/G | 21,089 | 0.009 (0.001) | 3.77 × 10−12 | 0.01 | |||||

| 61 | PLT | rs708382 | 17 | 39,797,869 | 17q21.31 |

FAM171A2

–

ITGA2B |

T/C | 50,036 | 2.439 (0.431) | 1.51 × 10−8 | 0.46 | – | – |

| 62 | PLT | rs11082304 | 18 | 18,974,970 | 18q11.2 | CABLES1 | G/T | 58,215 | 2.48 (0.378) | 5.27 × 10−11 | 0.73 | Yes | – |

| 63 | MPV | rs12969657 | 18 | 65,687,475 | 18q22.2 | CD226 | T/C | 19,285 | 0.007 (0.001) | 3.36 × 10−11 | 0.38 | Yes | 6 |

| 64 | MPV | rs8109288 | 19 | 16,046,558 | 19p13.12 | TPM4 | A/G | 13,964 | 0.029 (0.004) | 1.15 × 10−11 | 0.14 | – | 3 |

| PLT | rs8109288 | 19 | 16,046,558 | G/A | 29,014 | 11.945 (1.892) | 2.75 × 10−10 | 0.04 | – | ||||

| 65 | PLT | rs17356664 | 19 | 50,432,610 | 19q13.32 | EXOC3L2 | C/T | 55,487 | 2.599 (0.415) | 3.60 × 10−10 | 0.07 | – | – |

| 66 | MPV | rs13042885 | 20 | 1,872,706 | 20p13 | SIRPA | C/T | 21,186 | 0.008 (0.001) | 5.56 × 10−14 | 0.56 | – | 6 |

| 67 | MPV | rs4812048 | 20 | 57,021,165 | 20q13.32 |

CTSZ

–

TUBB1 |

C/T | 20,811 | 0.008 (0.001) | 1.30 × 10−9 | 0.06 | – | – |

| 68 | PLT | rs1034566 | 22 | 18,364,276 | 22q11.21 | ARVCF | T/C | 61,469 | 2.128 (0.384) | 3.06 × 10−8 | 0.43 | – | – |

| 69 | PLT | rs6141 | 3 | 185,572,959 | 3q27 | THPO∥ | T/C | 39,366 | 2.467 (0.456) | 6.18 × 10−8 | 0.59 | Yes | 24, 8 |

Results are provided for the 68 loci and 84 sentinel SNPs reaching genome-wide significant (P≤5 × 10−8) association with PLT or MPV. Results for stages 1 and 2 of the analysis in Europeans are provided in Supplementary Table 2. MPV, mean platelet volume; PLT, platelet count.

Alleles are indexed to the forward strand of NCBI build 36.

Effect sizes in ln(fl) for MPV and 109 l−1 for PLT.

All P values are based on the inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis model (fixed effects).

TRIM58 identifies the only secondary signal identified in this study, derived from a genome-wide secondary signal discovery effort carried out by conditioning the discovery GWAS on all SNPs reaching significance in the stage 1 meta-analysis. The effects (s.e.) and P values reported are obtained in the secondary analysis. The corresponding values in the stage 1 analysis are effect (s.e.)=2.721 (0.542) and P=4.06 × 10−7. Further details of this analysis are given in the Supplementary Information.

THPO narrowly misses the level required for nominal significance (P<5 × 10−8) in Europeans, but shows genome-wide significance in Japanese.

Rep. indicates replication of European stage 1+2 results in non-Europeans (Supplementary Table 3): yes, if association P value is at least in one non-European population <0.0007 (to account for multiple testing of 68 loci).

Relevant references are indicated.

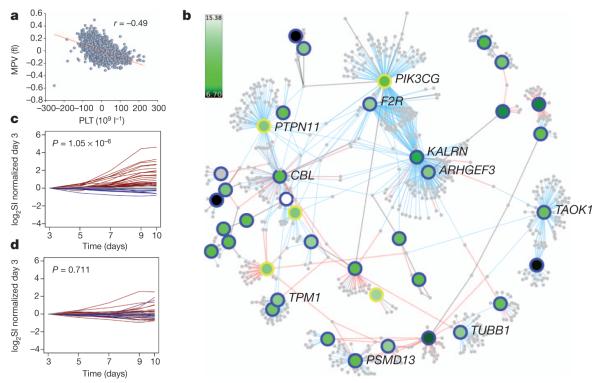

Figure 1. Protein-protein interaction network and gene transcription patterns.

a, Negative correlation between PLT and MPV in a UK sample. The gender-adjusted correlation coefficient r and trend line are shown. b, Protein–protein interaction network of platelet loci. For the nodes, genes are represented by round symbols, where node colour reflects gene transcript level in megakaryocytes on a continuous scale from low (dark green) to high (white). Grey-coloured round symbols identify first-order interactors identified in Reactome and IntAct. Core genes not connected to the main network are omitted. The 34 core genes are identified by a blue perimeter. Yellow perimeters identify five additional genes (VWF, PTPN11, PIK3CG, NFE2 and MYB) with known roles in haemostasis and megakaryopoiesis and mapping to within the association signals at distances greater than 10 kb from the sentinel SNPs. These genes, which do not conform to the rule for inclusion into the core gene list, are not considered in further analyses presented in Fig. 2c, d and Supplementary Fig. 5 and are shown here for illustration purposes only. Network edges were obtained from the Reactome (blue) and IntAct-like (red) databases and through manual literature curation (black). The network including the 34 core genes alone contains 633 nodes and 827 edges; after inclusion of the 5 additional genes, the network (shown here) includes 785 nodes and 1,085 edges. The full network, containing gene expression levels and other annotation features, is available in Cytoscape25 format for download (Supplementary Data 1). c, d, Time course experiments of gene expression in megakaryocytes and erythroblasts. Expression of core genes in log2 transformed signal intensities (log2 SI) during differentiation of the haematopoietic stem cells into megakaryocytes (c) or erythroblasts (d), segregated by their trends of statistically significant increasing (red), decreasing (blue) or unchanged (grey) gene expression. The corresponding gene list for the three classes is given in Supplementary Data 1.

We further tested the association of the 68 loci in 7,949 (MPV) and 8,295 (PLT) samples of south Asian and 14,697 (PLT) samples of Japanese8 origin. We detected substantial overlap of association signals, with effect size and direction highly concordant with findings in Europeans (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 3). In the south Asian sample, 15 of the 68 (22.1%) loci were significant after adjustment for multiple testing (P ≤ 7 × 10−4). In the Japanese sample, 13 of 55 (23.6%) PLT loci showed significance. Moreover, 73 of 84 (87%, South Asians) and 45 of 55 (82%, Japanese) SNPs showed associations with effect estimates directionally consistent with Europeans. Such concordance is highly unlikely to be due to chance (P = 2.3 × 10−12 and P = 2.1 × 10−6), and provides independent validation of the locus discovery in Europeans.

The 68 loci cumulatively explain 4.8% of the phenotypic variance in PLT and 9.9% in MPV, accounting respectively for average increases of 2.57 × 109 l−1 PLT and 0.10 fl MPV per copy of allele. These levels of explained variance are in accordance with other GWAS of complex quantitative traits9. Our results indicate that many other common variants of similar or lower effect size, rare variants as well as structural variants may also contribute to the variation of both platelet traits. We used the method of ref. 10 to estimate the number of additional PLT- and MPV-associated loci having effect sizes comparable to those observed in our analysis. The method (with caveats discussed in the Supplementary Information) predicted that 137 and 81 such loci exist for PLT and MPV respectively, accounting for 9.7% and 18.3% of the total phenotypic variance.

Gene-prioritization strategies

Evidence from recent, highly powered meta-analyses suggests that the association peaks are enriched for genes controlling key underlying biological pathways11,12. In our case, a large proportion of the association signals (46 out of 68) had the most significant SNP in stage 1 (‘sentinel SNP’) mapping to within a gene-coding region, including several key regulators of haemostasis (ITGA2B, F2R, GP1BA), megakaryopoiesis (THPO, MEF2C) and platelet lifespan (BAK1). Through an unbiased analysis of our GWAS results, we estimated that PLT-associated SNPs are significantly more likely to map to gene regions than expected by chance (P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting that we may prioritize the search of additional yet unknown genes controlling these processes in the associated regions. To define a univocal rule to study the enrichment of functional relationships in associated genes, we made the choice to focus on a set of 54 ‘core’ genes selected as either containing the sentinel SNP or mapping to within 10 kb from an intergenic sentinel SNP (Table 2). This selection strategy is designed to obtain unbiased hypotheses producing interpretable biological inference for genes near the association signals, but has reduced sensitivity for genes that map further from the sentinel SNP. For instance VWF, a key regulator of haemostasis, maps to 55 kb from the sentinel SNP (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 4) and is therefore not considered as a core gene. We further note that this selection strategy does not imply knowledge of the location of causative variants, which is currently incomplete. A detailed SNP survey showed that at 15 loci the sentinel SNPs either encoded, or were in high linkage disequilibrium (LD, r2 ≥ 0.8) with, a non-synonymous variant (Supplementary Table 5); another 11 either matched or were in high linkage disequilibrium with SNPs associated with expression levels of core genes (or cis-eQTLs, Supplementary Table 6), indicating that other loci may exert their effect through regulation of gene expression13. The validation of suggestive causative effects, as well as the identification of more complex interactions involving other genomic loci (trans eQTLs), will require a more comprehensive discovery in appropriately powered genomic data sets.

Table 2. Summary of functional evidence for core genes.

| Sentinel SNP (trait) | Core gene (distance in kb)* | Phenotype† |

|---|---|---|

| rs17396340 (MPV) | KIF1B kinesin family member 1B (0) | Variant annotation: sentinel SNP in r2 = 1 with eQTL for K1F1B |

| rs2336384 (PLT) | MFN2 mitofusin 2 (0) | Variant annotation: sentinel SNP is eQTL for MFN2 |

| rs10914144 (MPV, PLT) | DNM3 dynamin 3 (0) |

shibire (DNM-like): overproliferation of plasmatocytes in Drosophila (this study) |

| rs1172130, rs1668871 (MPV, PLT) |

TMCC2 transmembrane and coiled-coil domain family 2 (2,481; 0) |

Variant annotation: sentinel SNP in r2 = 0.928 with eQTL for RIPK5 |

| rs1260326 (PLT) | GCKR glucokinase (hexokinase 4) regulator (0) |

Xab1 (non-core gene): pronounced increase in plasmatocyte and crystal cell counts in Drosophila (this study) |

| rs649729, rs625132 (MPV, PLT) |

EHD3 EH-domain-containing 3 (0) |

ehd3 morpholino-injected embryos had no haematopoietic phenotype in D. rerio (this study) |

| rs17030845 (PLT) | THADA thyroid adenoma associated (0) | Zfp36l2 (non-core gene): decreased platelet cell number in mouse |

| rs1354034 (MPV, PLT) |

ARHGEF3 Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 3 (0) |

arhgef3: profound effect on thrombopoiesis and erythropoiesis in D. rerio (this study) |

| rs2227831, rs17568628 (MPV, PLT) |

F2R coagulation factor II (thrombin) receptor (0; 15,343) |

Par1 (F2R): thrombin activation of platelets attenuated in mouse |

| rs700585, rs4521516 (PLT, MPV) |

MEF2C myocyte enhancer factor 2C (0) |

Mef2: severely impaired megakaryopoiesis with reduced platelet count and increased platelet volume in mouse |

| rs2070729 (PLT) | IRF1 interferon regulatory factor 1 (0) | Irf1: decreased number of NK lymphocytes in mouse |

| rs10076782 (MPV) | RNF145 ring finger protein 145 (0) | rnf145: ablation of thrombopoiesis and erythropoiesis in D. rerio (this study) |

| rs210134 (PLT) | BAK1 BCL2-antagonist/killer 1 (116) |

Bak1: genetic ablation of Bcl-xl in mouse leads to thrombocytopenia by reducing platelet lifespan and this is corrected by ablation of Bak1 |

| rs6993770 (PLT) | ZFPM2 zinc finger protein, multitype 2 (0) |

Zfpm2: peripheral haemorrhage in mouse; ush (ZFPM2): reduction in plasmatocytes and crystal cells in Drosophila (this study) |

| rs6995402 (PLT) | PLEC1 plectin (0) | Plec1: impaired leukocyte recruitment to wounds in mouse |

| rs10813766 (MPV) | DOCK8 dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (0) |

Dock8: decrease in number of B cells and T cells in mouse; autosomal recessive hyper-IgE recurrent infection syndrome (OMIM: 243700) |

| rs409801 (PLT) | AK3 adenylate kinase 3 (2,699) | ak3: ablation of thrombopoiesis and erythropoiesis in D. rerio (this study) |

| rs7075195, rs10761731 (MPV, PLT) |

JMJD1C jumonji domain containing 1C (0) | jmjd1c: ablation of thrombopoiesis and erythropoiesis in D. rerio (this study) |

| rs505404, rs17655730 (PLT, MPV) |

PSMD13 proteasome (prosome, macropain) 26S subunit, non-ATPase, 13 (0); NLRP6 NLR family, pyrin domain containing 6 (7,856) |

rpn9 (PSMD13): reduction in plasmatocyte numbers in Drosophila (this study) |

| rs4246215 (PLT) | FEN1 flap structure-specific endonuclease 1 (0) | Variant annotation: sentinel SNP is eQTL for CPSF7; Fads2 (non-core gene): abnormal platelet physiology and decreased platelet aggregation in mouse |

| rs4938642 (PLT) |

CBL Cas-Br-M (murine) ecotropic retroviral transforming sequence (0) |

Acute myeloid leukaemia (OMIM: 165360); Cbl: increased platelet numbers, increased thymic CD3 and CD4 expression on T cells in mouse; haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells showed enhanced sensitivity to cytokines in Cbl-null mice |

| rs10876550 (MPV) | COPZ1 coatomer protein complex, subunit zeta 1 (6,604) | Variant annotation: sentinel SNP is eQTL for GPR84; Copz1: iron deficiency in mouse; Nfe2 (non-core): thrombocytopenia in mouse; Znf385a (non-core): abnormal platelet morphology in mouse; Su(var)205 (non-core CBX5): reduction in plasmatocyte number and overproliferation of crystal cells in Drosophila (this study) |

| rs3184504 (PLT) | SH2B3 SH2B adaptor protein 3 (0) |

Lnk (SH2B3): increased megakaryopoiesis and platelet count in mouse; increased white blood cell counts and decreased platelet count in mouse; rpl6 (non-core): reduced plasmatocyte and crystal cell number in Drosophila (this study) |

| rs4148441 (PLT) |

ABCC4 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 4 (0) |

ABCC4 is an active constituent of mediator-storing granules in human platelets |

| rs7317038 (MPV) | GRTP1 growth hormone regulated TBC protein 1 (0) | Variant annotation: sentinel SNP is eQTL for GRTP1; sentinel SNP in r2 = 0.93 with eQTL for RASA3 |

| rs3000073 (MPV) |

BRF1 BRF1 homologue, subunit of RNA polymerase III transcription initiation factor IIIB (S. cerevisiae) (0) |

brf: reduction in plasmatocyte cell number in Drosophila (this study) |

| rs3809566 (PLT) | TPM1 tropomyosin 1 (alpha) (1,115) | Variant annotation: sentinel SNP in r2=1 with eQTL for TPM1; tpma (TPM1): total abrogation of thrombopoiesis, but normal erythropoiesis in D. rerio (this study) |

| rs6065 (PLT) | GP1BA glycoprotein Ib (platelet), alpha polypeptide (0) | Bernard–Soulier syndrome (OMIM: 231200), benign Mediterranean macrothrombocytopenia (OMIM: 153670), pseudo-von Willebrand disease (OMIM: 177820); Gp1ba: giant platelets, a low platelet count and increased bleeding in mouse; Gp1ba+/− mice show complete inhibition of arterial thrombus formation and intermediate platelet numbers |

| rs708382 (PLT) |

FAM171A2 family with sequence similarity 171, member A2 (1,108); ITGA2B integrin, alpha 2b (7,207) |

Glanzmann thrombasthenia (OMIM: 607759); decreased platelet count, abnormal platelet morphology and decreased platelet aggregation in mouse; itga2b: severely reduced thrombocyte function in D. rerio |

| rs12969657 (MPV) | CD226 CD226 molecule (0) | Variant annotation: sentinel SNP is eQTL for CD226; leukocyte adhesion deficiency (OMIM: 116920); CD226 mediates adhesion of megakaryocytic cells to endothelial cells and inhibition of this diminishes megakaryocytic cell maturation; Dnam1 (CD226): cytotoxic T cells and NK cells less able to lyse tumours in mouse |

| rs13042885 (MPV) | SIRPA signal-regulatory protein alpha (4,163) |

Sirpa: mild thrombocytopenia in mouse, decreased proportion of single positive T cells, enhanced peritoneal macrophage phagocytosis |

| rs4812048 (MPV) | CTSZ cathepsin Z (5,468); TUBB1 tubulin, beta 1 (6,539) | Autosomal dominant macrothrombocytopenia (OMIM: 613112); Tubb1: thrombocytopenia resulting from a defect in generating proplatelets in mouse; prolonged bleeding time and attenuated response of platelets to thrombin in mouse; sun (non-core ATP5E): reduction of crystal cell numbers in Drosophila (this study) |

| rs1034566 (PLT) |

ARVCF armadillo repeat gene deleted in velocardiofacial syndrome (0) |

Variant annotation: sentinel SNP in r2 = 1 with eQTL for UFD1L |

| rs6141 (PLT) | THPO thrombopoietin (0) | Essential thrombocythemia (OMIM: 187950); Thpo: decrease in platelet number and increase in platelet volume in mouse |

Information is given only for genes with a haematopoietic phenotype. A more extensive annotation of genes within associated intervals is presented in Supplementary Table 4. Information on variants associated with gene expression is presented in Supplementary Table 6. No evidence for a haematopoietic effect was associated with the following core genes: rs3811444 (PLT) (TRIM58 tripartite motif-containing 58 (0)); rs4305276 (MPV) (ANKMY1 ankyrin repeat and MYND domain containing 1 (0)); rs3792366 (PLT) (PDIA5 protein disulphide isomerase family A, member 5 (0)); rs10512627 (MPV) (KALRN kalirin, RhoGEF kinase (0)); rs11734132 (MPV) (KIAA0232 (5,628)); rs441460 (PLT) (LRRC16A leucine-rich-repeat containing 16A (0)); rs13300663 (PLT) (RCL1 RNA terminal phosphate cyclase-like 1 (0)); rs3731211 (PLT) (CDKN2A cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (0)); rs2950390, rs941207 (MPV, PLT) (PTGES3 prostaglandin E synthase 3 (cytosolic) (1,871); BAZ2A bromodomain adjacent to zinc finger domain, 2A (0)); rs7961894 (MPV, PLT) (WDR66WD repeat domain 66 (0)); rs8022206 (PLT) (RAD51L1 RAD51-like 1 (S. cerevisiae) (0)); rs8006385 (PLT) (ITPK1 inositol-tetrakisphosphate 1-kinase (0)); rs2297067, rs944002 (PLT, MPV) (C14orf73 exocyst complex component 3-like 4 (0)); rs8076739, rs559972 (MPV, PLT) (TAOK1 TAO kinase 1 (3,357, 0)); rs1697127 (MPV) (AP2B1 adaptor-related protein complex 2, beta 1 subunit (0)); rs11082304 (PLT) (CABLES1 Cdk5 and Abl enzyme substrate 1 (0)); rs8109288 (MPV, PLT) (TPM4 tropomyosin 4 (0)), rs17356664 (PLT) (EXOC3L2 exocyst complex component 3-like 2 (3,301)); rs2015599 (MPV) (FAR2 fatty acyl CoA reductase 2 (0)); rs397969 (PLT) (AKAP10 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 10 (4,506)); rs11789898 (PLT) (BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 (0)).

Core genes are defined as either containing a sentinel SNP or as mapping at less than 10 kb from an intergenic SNP. Distance from nearest gene is calculated as the absolute distance between SNP and transcription start site of the gene or 3′ end of last exon.

Phenotypes are defined from exhaustive search of the OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man) database, published in vitro studies for humans and knockout and knockdown experiments for model organisms for both core and non-core genes. r2 values are calculated from the HapMap phase 2 CEU panel. Drosophila indicates Drosophila melanogaster.

As a first effort to characterize biological connectivity among the core genes, we applied canonical pathway analyses (see http://www.ingenuity.com), detecting a highly significant over-representation of core genes in relevant biological functions such as haematological disease, cancer and cell cycle (Supplementary Table 7). Encouraged by these results, we extended this effort to construct a comprehensive network of protein-protein interactions incorporating the core genes. This effort integrated information from public databases (principally Reactome and IntAct) with careful manual revision of published evidence and high-throughput gene expression data. The resulting network, which includes 633 nodes and 827 edges, showed extensive connectivity between the proteins encoded by the core genes with an established functional role in megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation and those encoded by genes hitherto unknown to be implicated in these processes (Fig. 1b).

Transcriptional patterns of core genes

We next considered whether this connectivity was also reflected in the regulation of core gene transcription, and whether expression patterns were unique to megakaryocytes. Despite high levels of correlation in gene expression between different blood cell types (median 5 0.8; median absolute deviation = 0.1)14, we found that core genes tend to have significantly greater expression in megakaryocytes than in the other blood cells (P = 7.5 × 10−5, Supplementary Fig. 5a). This observation is compatible with the notion that ultimate steps in blood cell lineage specification are accompanied, or driven, by the emergence of increasing numbers of lineage-specific transcripts. To explore this assumption, we used genome-wide expression arrays to determine changes in global transcript levels during in vitro differentiation of umbilical-cord blood-derived haematopoietic stem cells to precursors of blood cells. We considered five different time points and two cell types, erythroblasts (the precursors of red blood cells) and megakaryocytes. Notwithstanding high levels of correlation of gene expression between erythroblasts and megakaryocytes14, core gene transcripts showed a significant increase over time in megakaryocytes (P = 1.5 × 10−6) but not in erythroblasts (P = 0.77, Fig. 1c, d; see also Supplementary Fig. 5b). Taken together, these patterns of core gene expression are consistent with a different regulation of their transcription in megakaryocytes versus erythroblasts, and with their centrality in megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. This hypothesis is also consistent with the observation that only 5 of the 68 sentinel SNPs exert a significant effect on erythrocyte parameters (HBS1L-MYB, RCL1, SH2B3, TRIM58 and TMCC2, Supplementary Table 8).

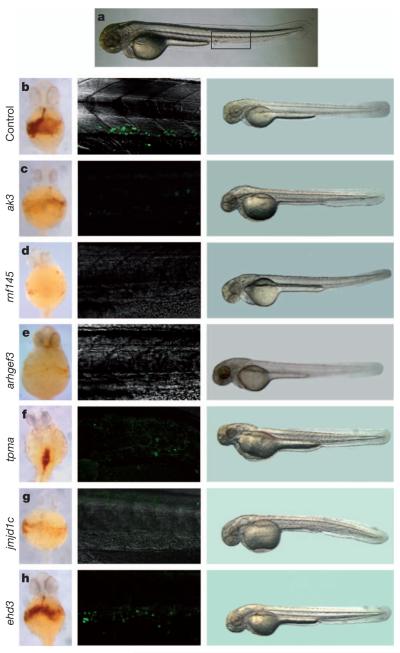

Gene silencing in model organisms

To assess whether core genes are indeed implicated in haematopoiesis, we interrogated the function of 15 genes using gene silencing in D. rerio and D. melanogaster, and supported empirical data with published evidence on knockout models in M. musculus (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4). In D. rerio, we applied morpholino constructs to silence the expression of six genes (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6) selected to have >50% homology with the human counterpart and no previous evidence of involvement in haematopoiesis. Silencing of four genes in D. rerio (arhgef3, ak3, rnf145, jmjd1c) resulted in the ablation of both primitive erythropoiesis and thrombocyte formation. Silencing of tpma, the orthologue of TPM1 that is transcribed in megakaryocytes but not in other blood cells, abolished the formation of thrombocytes but not of erythrocytes. Silencing of ehd3 did not yield a haematopoietic phenotype. We also screened D. melanogaster RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown lines for quantitative alterations in the two most prevalent classes of blood elements: plasmatocytes and crystal cells. The repertoire of blood cells in D. melanogaster, consisting of about 95% plasmatocytes and 5% crystal cells, is less varied than in vertebrates. Transcription factors and signalling pathways regulating haematopoiesis have, however, been conserved throughout evolution15, making the RNAi knockdown studies a relevant first step towards a better understanding of the putative role of these GWAS genes in haematopoiesis. Four core-gene D. melanogaster lines (shibire (DNM), ush (ZFPM2), rpn9 (PSMD13), Brf (BRF1)), as well as five others (sun (ATP5E), CG3704 (XAB1), Su(var)205 (CBX5), dve (SATB1) and RpL6 (RPL6)), displayed highly reproducible differences in the numbers of these two cell types (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4). Despite widespread differences between mammalian and insect haematopoietic lineages16, our findings from D. melanogaster provide new and supporting examples of functional conservation in the control of blood cell formation in invertebrates and vertebrates17-19.

Figure 2. Functional assessment of novel loci in D. rerio.

Gene-specific morpholinos were injected into wild-type and Tg(cd41:EGFP) embryos at the one cell stage (Supplementary Fig. 6) to assess alterations in erythropoiesis and thrombopoiesis. a, Control D. rerio embryo at 72 h post fertilization (h.p.f.); the boxed region corresponds to images in the middle panels of b–h. b–h, Left: o-dianisidine staining was used to assess the number of mature erythrocytes at 48 h.p.f.: ehd3 (h) morpholino-injected embryos showed normal haemoglobin staining, whereas embryos injected with ak3 (c), rnf145 (d), arhgef3 (e) or jmjd1c (g) morpholinos showed a decrease in the number of haemoglobin-positive cells compared to control embryos (b). Embryos injected with tpma morpholinos (f) showed normal numbers of erythrocytes but unusual accumulation dorsally in the blood vessels (compatible with cardiomyopathy). Middle: haematopoietic stem-cell and thrombocyte development was assessed using the transgenic Tg(cd41:EGFP) line at 72 h.p.f. Embryos injected with the ehd3 (h) morpholino had a normal number of GFP1 cells in the caudal haematopoietic tissue and circulation, when compared to control embryos (b). However, GFP1 cells were absent in ak3 (c), rnf145 (d), arhgef3 (e), tpma (f) and jmjd1c (g) morpholino-injected embryos. Right: One-cell-stage embryos were injected with the standard control morpholino (b) or gene-specific morpholino (c–h) and monitored during development. No gross lethality or developmental abnormalities were observed at 72 h.p.f. in gene-specific morpholino-injected embryos (c–h) compared with the control (b). a and middle and right panels of b–h, lateral view, anterior left; left panels of b–e, g, h, ventral view, anterior up; left panel of f, dorsal view, anterior up. The genes appear to be nonspecifically expressed during embryogenesis as shown by patterns deposited in the ZFIN resource (http://zfin.org).

New gene and functional discoveries

The data from studies in D. rerio by us and in M. musculus by others (see Supplementary Table 4) provided proof-of-concept evidence that our prioritization strategy is appropriate for selecting novel genes controlling thrombopoiesis and megakaryopoiesis, respectively. More detailed insights and additional implicated genes will be revealed through the systematic silencing of all genes in the associated regions. For instance, RNAi knockdown of dve in D. melanogaster reduces plasmatocyte numbers and increases the number of crystal cells, thus providing supporting evidence that its non-core genehuman homologue SATB1 should be prioritized in functional studies. However, the results of the knockdown study in D. rerio do not clarify at which hierarchical positions in thrombopoiesis and erythropoiesis the genes exert their effect, requiring further assessment in conditional knockout models in M. musculus with lineage-specific regulation of gene transcription. Nevertheless, our results have already allowed novel insights into the genetic control of these processes. Signalling cascades initiated by thrombopoietin (THPO) and its receptor cMPL via the JAK2/STAT3/5A signalling pathway are key regulatory steps initiating changes in gene expression responsible for driving forward megakaryocyte differentiation20. Our study highlights several additional signalling proteins implicating potentially important novel regulatory routes. For instance, two genes encoding guanine nucleotide exchange factors (DOCK8 and ARHGEF3) were identified. Mendelian mutations of the former are causative of the hyper-IgE syndrome, but its effect on platelets had not yet been identified. The silencing of the latter gene in D. rerio resulted in a profound haematopoietic phenotype characterized by a complete ablation of both primitive erythropoiesis and thrombocyte formation, demonstrating its novel regulatory role in myeloid differentiation. In a parallel and in-depth study we demonstrated its novel role in the regulation of iron uptake and erythroid cell maturation21. A second class of genes also known to critically control early and late events of megakaryopoiesis are transcription factors. For instance, MYB silencing by microRNA 150 determines the definitive commitment of the megakaryocyte–erythroblast precursor to the megakaryocytic lineage15. A further 10 core genes identified in this study are implicated in the regulation of transcription. Among these, we have demonstrated here that silencing of rnf145 and jmjd1c in D. rerio severely affects both lineages.

In conclusion, this highly powered study describes a catalogue of known and novel genes associated with key haematopoietic processes in humans, providing an additional example of GWAS leading to biological discoveries. We further showed that for a large proportion of these known and new genes, functional support is achieved from model organisms and by overlap with genes implicated in inherited Mendelian disorders and in human cancers because of acquired mutations. In-depth functional studies and comparative analyses will be necessary to characterize the precise mechanisms by which these new genes and variants affect haematopoiesis, megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. Furthermore, we provide extensive new resources, most notably a freely accessible knowledge base embedded in the novel protein-protein interaction network, with information about the identified platelet genes being implicated in Mendelian disorders and results from gene-silencing studies in model organisms. We anticipate that these resources will help to advance megakaryopoiesis research, to address key questions in blood stem-cell biology and to propose new targets for the treatment of haematological disorders. Finally, MPV has been associated with the risk of myocardial infarction22,23. The contribution of the new loci to the aetiology of acute myocardial infarction events will require assessment in a prospective setting.

METHODS SUMMARY

A summary of the methods can be found in Supplementary Information and includes detailed information on: study populations; blood biochemistry measurements; genotyping methods and quality control filters; genome-wide association and meta-analysis methods; gene prioritization strategies for functional assessment and network construction; protein-protein interaction network; in vitro differentiation of blood cells; experimental data sets and analytical methods for gene expression analysis; zebrafish morpholino knockdown generation; assessment of other model organism resources.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Reactome is supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (P41 HG003751), EU grant LSHG-CT-2005-518254 ‘ENFIN’, and the EBI Industry Programme. A.C. and D.L.S. are supported by the Wellcome Trust grants WT 082597/Z/07/Z and WT 077037/Z/05/Z and WT 077047/Z/05/Z, respectively. J.S.C. and K.V. are supported by the European Union NetSim training fellowship scheme (number 215820). A. Radhakrishnan, A.A., H.L.J., J.J., J.S. and W.H.O. are funded by the National Institute for Health Research, UK. Augusto Rendon is funded by programme grant RG/09/012/28096 from the British Heart Foundation. J.M.P. is supported by an Advanced ERC grant. IntAct is funded by the EC under SLING, grant agreement no. 226073 (Integrating Activity) within Research Infrastructures of the FP7, under PSIMEX, contract no. FP7-HEALTH-2007-223411. C.G. received support by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013), ENGAGE Consortium, grant agreement HEALTH-F4-2007-201413. N.S. is supported by the Wellcome Trust (Grant Number 098051). Acknowledgements by individual participating studies are provided in Supplementary Information.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions Study design group: C.G., S. Sanna, A.A.H., A. Rendon, M.A.F., W.H.O., N.S.; manuscript writing group: C.G., A. Radhakrishnan, S. Sanna, A.A.H., A. Rendon, M.A.F., W.H.O., N.S.; data preparation, meta-analysis and secondary analysis group: A. Radhakrishnan, B.K., W.T., E.P., G.P., R.M., M.A.F., C.G., N.S.; bioinformatics analyses, pathway analyses and protein-protein interaction network group: S.M., J.-W.N.A., S.J., J.K., Y.M., L.B., A. Rendon, W.H.O.; transcript profiling methods and data group: K.V., A. Rendon, L.W., A.H.G., T.-P.Y., F. Cambien, J.E., C. Hengstenberg, N.J.S., H. Schunkert, P.D., W.H.O.; M. musculus models: R.R.-S.; D. rerio knockdown models: A.C., J.S.-C., D. Stemple, W.H.O.; D. melanogaster knockdown models: U.E., J. Penninger and A.A.H. All other author contributions and roles are listed in Supplementary Information.

References

- 1.Frazer KA, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devlin B, Roeder K. Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics. 1999;55:997–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lo KS, et al. Genetic association analysis highlights new loci that modulate hematological trait variation in Caucasians and African Americans. Hum. Genet. 2011;129:307–317. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0925-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meisinger C, et al. A genome-wideassociation study identifies three loci associated with mean platelet volume. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soranzo N, et al. A novel variant on chromosome 7q22.3 associated with mean platelet volume, counts, and function. Blood. 2009;113:3831–3837. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soranzo N, et al. A genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 22 loci associated with eight hematological parameters in the HaemGen consortium. Nature Genet. 2009;41:1182–1190. doi: 10.1038/ng.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bath PM, Butterworth RJ. Platelet size: measurement, physiology and vascular disease. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis. 1996;7:157–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamatani Y, et al. Genome-wide association study of hematological and biochemical traits in a Japanese population. Nature Genet. 2010;42:210–215. doi: 10.1038/ng.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manolio TA, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park J-H, et al. Estimation of effect size distribution from genome-wide association studies and implications for future discoveries. Nature Genet. 2010;42:570–575. doi: 10.1038/ng.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lango Allen H, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467:832–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teslovich T, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466:707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul DS, et al. Maps of open chromatin guide the functional follow-up of genome-wide association signals: application to hematological traits. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watkins NA, et al. A HaemAtlas: characterizing gene expression in differentiated human blood cells. Blood. 2009;113:1–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu J, et al. MicroRNA-mediated control of cell fate in megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:843–853. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crozatier M, Meister M. Drosophila haematopoiesis. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9:1117–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fossett N, et al. The Friend of GATA proteins U-shaped, FOG-1, and FOG-2function as negative regulators of blood, heart, and eye development in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:7342–7347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131215798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldfarb AN. Transcriptional control of megakaryocyte development. Oncogene. 2007;26:6795–6802. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregory GD, et al. FOG1 requires NuRD to promote hematopoiesis and maintain lineage fidelity within the megakaryocytic-erythroid compartment. Blood. 2010;115:2156–2166. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-251280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wendling F, et al. cMpl ligand is a humoral regulator of megakaryocytopoiesis. Nature. 1994;369:571–574. doi: 10.1038/369571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serbanovic-Canic J, et al. Silencing of RhoA nucleotide exchange factor, ARHGEF3 reveals its unexpected role in iron uptake. Blood. 2011;118:4967–4976. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu SG, et al. Mean platelet volume as a predictor of cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:148–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klovaite J, Benn M, Yazdanyar S, Nordestgaard BG. High platelet volume and increased risk of myocardial infarction: 39,531 participants from the general population. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;9:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garner C, et al. Two candidate genes for low platelet count identified in an Asian Indian kindred by genome-wide linkage analysis: glycoprotein IX and thrombopoietin. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;14:101–108. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cline MS, et al. Integration of biological networks and gene expression data using Cytoscape. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:2366–2382. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.