Abstract

Objective:

To analyze mortality following groin hernia operations.

Summary Background Data:

It is well known that the incidence of groin hernia in men exceeds the incidence in women by a factor of 10. However, gender differences in mortality following groin hernia surgery have not been explored in detail.

Methods:

The study comprises all patients 15 years or older who underwent groin hernia repair between January 1, 1992 and December 31, 2005 at units participating in the Swedish Hernia Register (SHR). Postoperative mortality was defined as standardized mortality ratio (SMR) within 30 days, ie, observed deaths of operated patients over expected deaths considering age and gender of the population in Sweden.

Results:

A total of 107,838 groin hernia repairs (103,710 operations), were recorded prospectively. Of 104,911 inguinal hernias, 5280 (5.1%) were treated emergently, as compared with 1068 (36.5%) of 2927 femoral hernias. Femoral hernia operations comprised 1.1% of groin hernia operations on men and 22.4% of operations on women. After femoral hernia operation, the mortality risk was increased 7-fold for both men and women. Mortality risk was not raised above that of the background population for elective groin hernia repair, but it was increased 7-fold after emergency operations and 20-fold if bowel resection was undertaken. Overall SMR was 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.2–1.6) for men and 4.2 (95% confidence interval, 3.2–5.4) for women, in accordance with a greater proportion of emergency operations among women compared with men, 17.0%, versus 5.1%.

Conclusions:

Mortality risk following elective hernia repair is low, even at high age. An emergency operation for groin hernia carries a substantial mortality risk. After groin hernia repair, women have a higher mortality risk than men due to a greater risk for emergency procedure irrespective of hernia anatomy and a greater proportion of femoral hernia.

Mortality of patients having elective hernia repair is not raised above that of the general population, whereas emergency repair is associated with considerable mortality. Postoperative mortality is higher for women than for men because of a higher incidence of femoral hernia and a greater overall risk for emergency surgery.

Groin hernia surgery is a common procedure. The lifetime risk of having an inguinal or femoral hernia repair has been estimated to 27% for men and 3% for women.1 Whereas elective groin hernia repair is considered a low-risk procedure, emergency procedures have been associated with appreciable mortality. In the Swedish Hernia Register (SHR),2 each hernia operation is prospectively followed with 2 endpoints: reoperation in the same groin or death of patient. The aim of this study is to analyze mortality after hernia repair, considering age, gender, mode of admission (emergent or elective), and hernia anatomy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study comprises all patients 15 years or older who had a groin hernia repair (inguinal and femoral) between January 1, 1992 and December 31, 2004 at surgical units participating in the SHR. After each hernia operation, surgeons record data according to the SHR protocol, which includes time on waiting list, mode of admission, patient characteristics (ASA score included in registration from 2003), hernia (primary/recurrent, anatomy), method of repair, anesthesia, complication within 30 days of surgery, and reoperation for recurrence. Clinical follow-up is not mandatory, but any complication observed by the operating unit up to 30 days after surgery has to be recorded. The register has permission to use personal identification number unique for each Swedish citizen, which enables life tables to be adjusted for death of patients and to link recurrent hernias to previous operation(s). The number of aligned units and annual operations recorded have increased from 8 to 90 and from 1689 to 16,783, respectively, from 1992 through 2004. In 2004, approximately 95% of all hernia operations performed in Sweden were documented in the SHR.

Each year an external reviewer visits some of the aligned units and compares register data with a sample of operative records and patient files to check the validity of register data. The register has been found to include some 98% of eligible operations.

For the present study, any combination of hernias that includes a femoral hernia is classified as femoral hernia. Combined hernias of other types or hernias not classified as femoral, direct, or indirect inguinal hernia are grouped as “other hernias” and included among inguinal hernias. Operation within 24 hours after emergency admission for groin hernia is classified as “acute or emergency operation.”

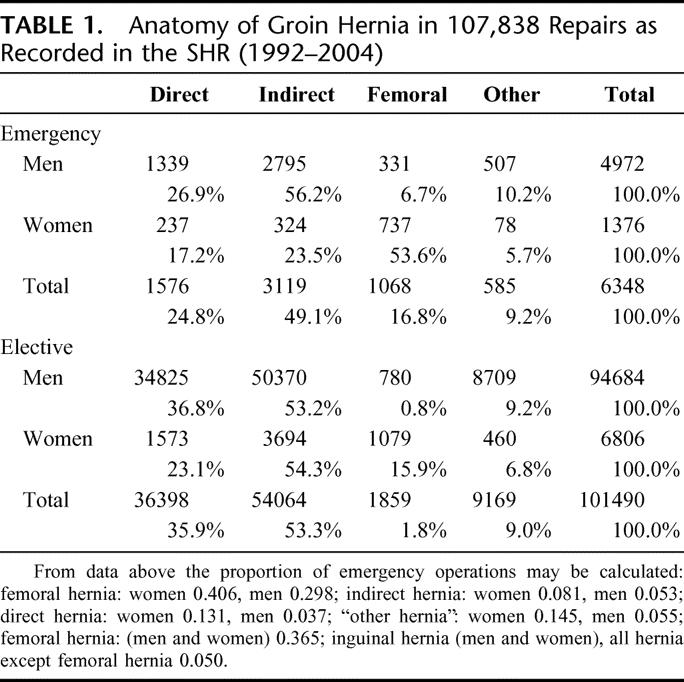

Postoperative mortality risk is defined as standardized mortality ratio (SMR), ie, ratio between observed and expected deaths within 30 days of surgery (irrespective of whether death occurred within or outside hospital) considering age and sex of the population in Sweden. Information concerning mortality of patients was reached by linking vital statistics and SHR. Vital statistics were obtained from Statistics Sweden, www.scb.se (Table 1; death rates by sex and age, 1994–2003); 2001 was chosen as reference year. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 12.0.1 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI) were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution of the number of events and given within parentheses. χ2 test was used for comparison between groups.

TABLE 1. Anatomy of Groin Hernia in 107,838 Repairs as Recorded in the SHR (1992–2004)

The study was approved by the Ethics committee of Linköping university, Sweden.

RESULTS

Table 1 illustrates anatomy of all 107,838 hernias as classified by Swedish surgeons. For all of hernias combined and for all hernia types considered separately emergency operations were more common among women than men. Thus, 40.6% of femoral hernias in women and 29.8% in men versus 8.1% and 5.3% of indirect hernias were treated emergently. For both genders combined, an emergency operation was required for 36.5% of femoral hernias in contrast to 5.0% of inguinal hernias (P < 0.001).

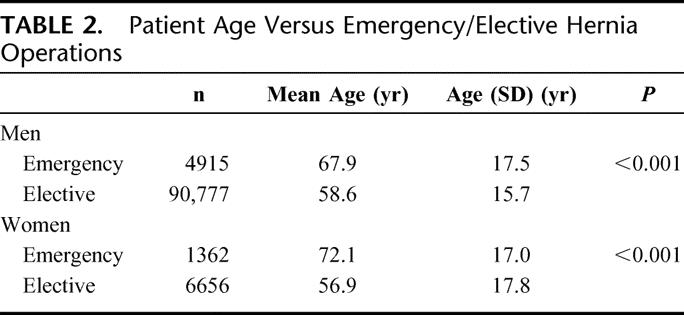

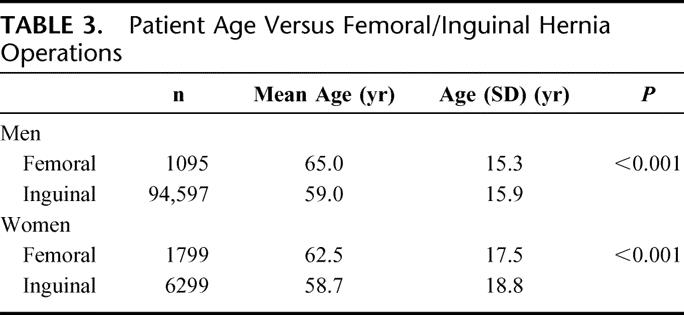

Both men and women undergoing an emergent hernia operation are significantly older than patients treated electively, and femoral hernia patients are older than inguinal hernia patients (Tables 2 and 3). After adjustment for gender, the mean age of patients with an emergency operation is 70.0 years (69.5–70.5 years) compared with 57.8 years (57.6–58.0 years) for patients with elective hernia repair and 63.7 years (63.1–64.3 years) for patients with femoral hernia repair compared with 58.8 years (58.6–59.0 years) for inguinal hernia patients.

TABLE 2. Patient Age Versus Emergency/Elective Hernia Operations

TABLE 3. Patient Age Versus Femoral/Inguinal Hernia Operations

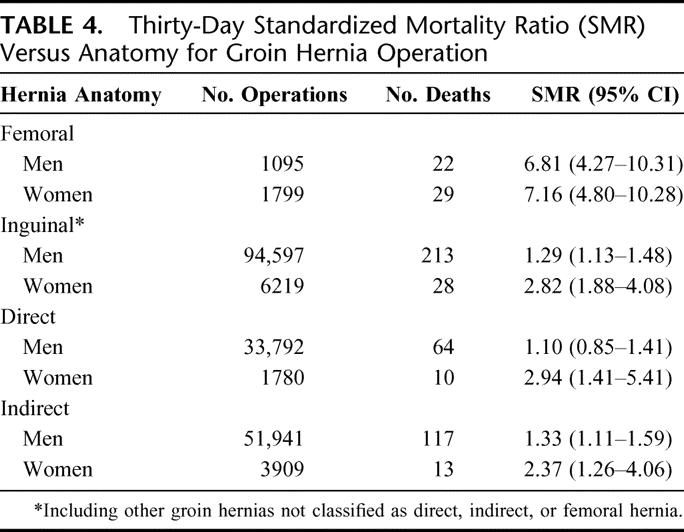

As demonstrated in Table 4, surgery for all types of hernia with the exception of direct hernia in men is associated with an increased mortality risk. The 30-day SMR after a femoral hernia operation is raised 7-fold for both genders, whereas SMR following an inguinal hernia operation is increased only modestly compared with the death risk of the background population for both men (SMR, 1.29; 1.13–1.48) and women (SMR, 2.82; 1.88–4.08). An emergency femoral hernia operation is associated with SMR 9.71 (7.13–12.91). In contrast, SMR following an elective operation for a femoral hernia does not exceed that of the general population 1.49 (0.41–3.91). For inguinal hernia operations, SMR after emergency and elective operations are 5.94 (4.99–7.01) and 0.63 (0.52–0.76).

TABLE 4. Thirty-Day Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) Versus Anatomy for Groin Hernia Operation

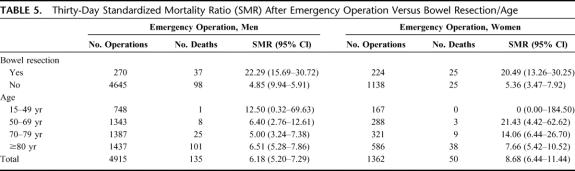

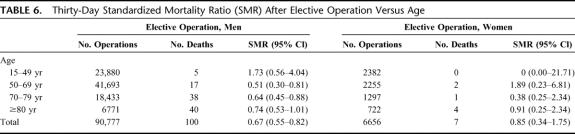

Overall mortality within 30 days after groin hernia operations is increased above that of the background population for all men and women (SMR, 1.40; 1.22–1.58 and 4.17; 3.16–5.40, respectively). This is due to the excess mortality following emergency operations, which constitute 4915 of 95,692 (5.1%) of operations on men and 1362 of 8018 (17.0%) of operations on women. The mortality risk following emergency operations for groin hernia is increased 6- to 9-fold compared with the mortality of the general population (Table 5). If bowel resection is undertaken, the risk is raised 20-fold. Bowel resection is undertaken in 226 of 1062 (21.3%) emergency femoral hernia operations compared with 268 of 4947 (5.4%) emergency inguinal operations (P < 0.001). Following an elective operation, 30-day mortality is lower than expected for both genders, significantly so for men, 0.67 (0.55–0.82), but not for women, 0.85 (0.34–1.75). It should be noted in Table 6 that the mortality risk after elective procedures tends to fall below unity even for patients aged 70 years or older.

TABLE 5. Thirty-Day Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) After Emergency Operation Versus Bowel Resection/Age

TABLE 6. Thirty-Day Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) After Elective Operation Versus Age

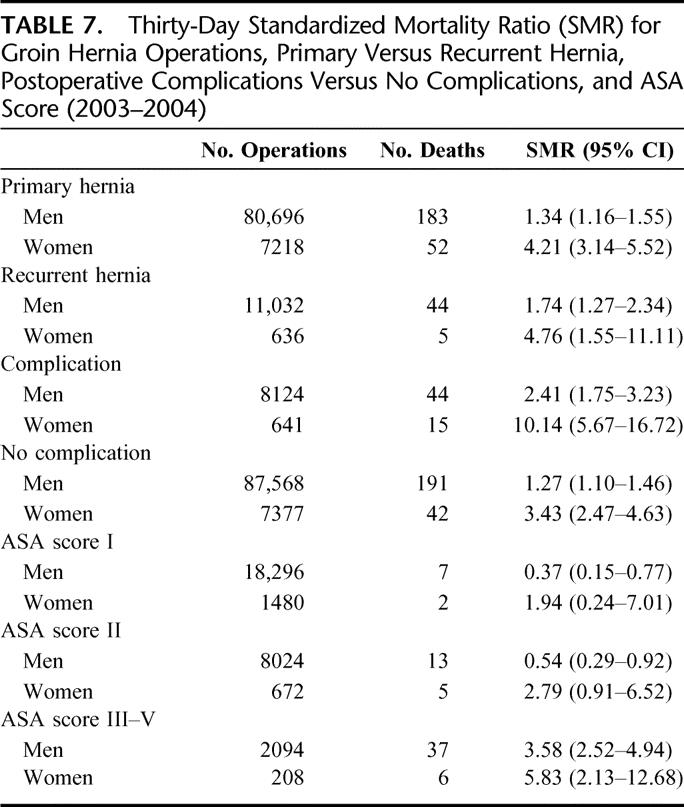

Table 7 illustrates that patients with ASA score I and II have a very low risk for postoperative mortality, whereas the mortality risk is raised significantly above that of the background population for both men and women with ASA score III to V. The notation of at least one complication raises the mortality risk, whereas primary or recurrent hernia operation does not affect the risk.

TABLE 7. Thirty-Day Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) for Groin Hernia Operations, Primary Versus Recurrent Hernia, Postoperative Complications Versus No Complications, and ASA Score (2003–2004)

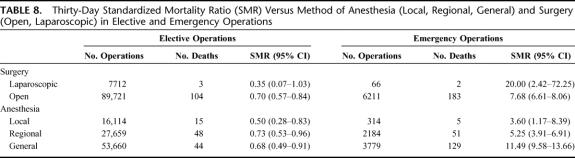

Local anesthesia carries a low risk compared with general and regional anesthesia in both elective and emergency operations (Table 8). The mortality risk is low following both open and laparoscopic elective operations but significantly increased above the expected level after emergency surgery.

TABLE 8. Thirty-Day Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) Versus Method of Anesthesia (Local, Regional, General) and Surgery (Open, Laparoscopic) in Elective and Emergency Operations

DISCUSSION

Elective hernia surgery is a low-risk procedure. Patients with emergency operations are approximately a decade older than patients treated electively. Emergency operations are 3 times more common in femoral than in inguinal hernia, and they carry a substantial mortality risk especially if bowel resection is performed. The excess postoperative mortality in women compared with men is due both to their high proportion of femoral hernia and to an increased risk for emergency procedure in all types of hernia. High ASA score and postoperative complication are associated with increased mortality risk, whereas primary or recurrent operation does not affect the risk.

Our study population is large, coverage nearly complete, and all data are prospectively recorded. Through personal identification number and linkage to official vital statistics, we have robust information on patients' death. The risk of death is given in relation to the death of the background population. We have, however, limited data on patient morbidity except ASA scores for 2 years.

The safety of local anesthesia makes it a favorable alternative whenever feasible.3–6 In the present study, methods of surgery did not significantly affect mortality. This should, however, be interpreted cautiously, as techniques are chosen with respect to morbidity of patients.

Our finding that the mortality following elective operations in men is lower than expected from death rates in the general Swedish population agrees with conclusions reached in a previous report from SHR7 and indicates that healthy patients are selected for planned hernia surgery. In accordance with previous studies,8–11 we found that also elective femoral hernia repair is associated with a very low mortality risk. Thus, the mortality risk in elective groin hernia surgery should not be a major issue when discussing indication for operation with a patient having a symptomatic hernia. Among symptomatic patients, those with a short duration of symptoms have a higher risk of requiring emergency surgery.12,13 It has been suggested that patients with vague symptoms and unfavorable medical conditions should be recommended elective hernia repair to avoid the high mortality associated with emergency repair.14 The present study support this view as elective hernia surgery, even at high age, does not raise the mortality risk above that of the general population, whereas emergency hernia surgery is associated with a substantial mortality risk.

As femoral hernias are more frequent among recurrent hernias than among primary hernias, it has been suggested that femoral hernias may be overlooked during repair of an inguinal hernia.8,15–17 (This is one possible explanation for the high proportion of female direct hernia in the present study, 17% of acute hernia and 23% elective hernia, although direct hernia is considered very rare in women.18) Hence, it may be appropriate to examine the femoral canal in inguinal hernia operations in order not to overlook a femoral hernia with its particular risk for emergency surgery, bowel resection, and postoperative mortality. This can be done by palpation through the hernia sac or by observing the femoral canal during a Valsalva maneuver if the repair is done in local anesthesia.

The high age of patients in need of emergency repair of groin hernia has been noted previously.19 Possible reasons for the high rate of emergency operation in femoral hernia found in this and earlier surveys8–11 are: no or vague symptoms prior to incarceration, diagnostic difficulties even at incarceration, and anatomic considerations that are outside the scope of the present study. Hjaltason20 reported that 15 of 46 patients with incarcerated femoral hernia were unaware of their hernias prior to hospital admission. Similarly, acute hospital admission was the first indication of hernia for 15 of 24 patients presenting with incarcerated femoral hernia in a recent survey.21 Diagnostic delay in incarcerated (femoral) hernia is associated with worse prognosis.9,22 In one report, strangulated hernias were misdiagnosed by the general practitioner in 33% of the patients and by the hospital registrar in 15%.23

There is an embarrassing lack of available information concerning the prevalence of groin hernia in the general population, in particular among women. The well-known study from Jerusalem24 addressed hernia prevalence in men exclusively. A more recent case-control study was concerned with potential risk factors in women undergoing elective inguinal hernia only.25 For men with ASA score I to III and minimally symptomatic inguinal hernia, watchful waiting is an acceptable option because of a low risk for hernia incarceration.26 As discussed above, the situation is quite different for femoral hernia due to its high rate of emergency surgery. Further epidemiologic studies concerning the prevalence of inguinal and femoral groin hernia among elderly individuals would be of value for healthcare planning.

Hernia is considered an avoidable cause of death,1,13,27 and this applies in particular to femoral hernia. The present findings have important consequences for populations of increasing age.28 During inguinal hernia repair, we should try to identify any concomitant femoral hernia. We should intensify our efforts to improve early diagnosis and treatment of patients with incarcerated and or strangulated hernia, and we must aim for optimizing perioperative care. Further, we should openly discuss elective operation with old and frail hernia patients and offer patients with femoral hernia early planned surgery, even if symptoms are vague or absent.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Lennart Gustafsson who provided invaluable help with statistics.

Footnotes

The Swedish Hernia Register is financially supported by the National Board of Health and Welfare and by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities.

Surgical units participating in SHR are described in: http://www.svensktbrackregister.se/kliniker.html

Reprints: Erik Nilsson, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Umeå University Hospital, SE90185 Umeå, Sweden. E-mail: erik.nilsson@surgery.umu.se

REFERENCES

- 1.Primatesta P, Goldacre MJ. Inguinal hernia repair: incidence of elective and emergency surgery, readmission and mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:835–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsson E, Haapaniemi S. Assessing the quality of hernia repair. In: Fitzgibbons R Jr, Greenburg AG, eds. Nyhus and Condon's Hernia, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002:567–573. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nehme AE. Groin hernias in elderly patients: management and prognosis. Am J Surg. 1983;146:257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callesen T, Bech K, Kehlet H. Feasibility of local infiltration anaesthesia for recurrent groin hernia repair. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:851–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordin P, Zetterström H, Gunnarsson U, et al. Local, regional, or general anaesthesia in groin hernia repair: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2003;362:853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nienhuijs SW, Remijn EEE, Rosman C. Hernia repair in elderly patients under unmonitored local anaesthesia is feasible. Hernia. 2006;9:218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haapaniemi S, Sandblom G, Nilsson E. Mortality after elective and emergency surgery for inguinal and femoral hernias. Hernia. 1999;4:205–208. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glassow F. Femoral hernia: review of 2,105 repairs in a 17 year period. Am J Surg. 1985;150:353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brittenden J, Heys SD, Eremin O. Femoral hernia: mortality and morbidity following elective and emergency surgery. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1991;35:86–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chamary VL. Femoral hernia: intestinal obstruction is an unrecognized source of morbidity and mortality. Br J Surg. 1993;80:230–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kemler MA, Oostvogel JM. Femoral hernia: is a conservative policy justified? Eur J Surg. 1997;163:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallegos NC, Dawson J, Jarvis M, et al. Risk of strangulation in groin hernias. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1171–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rai S, Chandra SS, Smile SR. A study of the risk of strangulation and obstruction in groin hernias. Aust NZ J Surg. 1998;68:650–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohana G, Manevwitch I, Weil R, et al. Inguinal hernia: challenging the traditional indication for surgery in asymptomatic patients. Hernia. 2004;8:117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch A, Edwards A, Haapaniemi S, et al. Prospective evaluation of 6895 groin hernia repairs in women. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1553–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bay-Nielsen M, Kehlet H. Inguinal herniorrhaphy in women. Hernia. 2006;10:30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikkelsen T, Bay-Nielsen M, Kehlet H. Risk of femoral hernia after inguinal herniorrhaphy. Br J Surg. 2002;89:486–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber A, Valencia S, Garteiz D Epidemiology of hernias in the female. In: Bendavid R, Abrahamson J, Arregui M, et al, eds. Abdominal Wall Hernias. New York: Springer, 2001:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malek S, Torella F, Edwards PR. Emergency repair of groin herniae: outcome and implications for elective surgery waiting times. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58:207–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hjaltason E. Incarcerated hernia. Acta Chir Scand. 1981;147:263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alani A, Page B, O'Dwyer PJ. Prospective study on the presentation and outcome of patients with an acute hernia. Hernia. 2006;10:62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Álvarez JA, Baldonedo RF, Bear IG, et al. Incarcerated groin hernias in adults: presentation and outcome. Hernia. 2004;8:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McEntee G, Pender D, Mulvin D, et al. Current spectrum of intestinal obstruction. Br J Surg. 1987;74:976–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abramson JH, Gofin J, Hopp C, et al. The epidemiology of inguinal hernia: a survey in western Jerusalem. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978;32:59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liem MSL, van der Graaf Y, Zwart RC, et al. Risk factor for inguinal hernia in women: a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitzgibbons R Jr, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gibbs JO, et al. Watchful waiting vs repair of inguinal hernia in minimally symptomatic men. JAMA. 2006;295:285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholson S, Keane TE, Devlin HB. Femoral hernia: an avoidable source of surgical mortality. Br J Surg. 1990;77:307–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Etzioni DA, Liu JH, Maggard MA, et al. The aging population and its impact on the surgery workforce. Ann Surg. 2003;238:170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]