The detectives at Sherlock Investigations get strange requests all the time. There was the mysterious disappearance of Captain Jack, an iguana that was stolen out the window of a ground-floor apartment on West Twelfth. Or the elderly woman in Peter Cooper Village who thought her neighbor was trying to kill her by shooting neutron beams through her kitchen wall. (They checked it out. She wasn’t.) Or the jealous husband in Park Slope. He suspected his wife was cheating on him, and with his father. (She was.) So the e-mail that came in on March 19 didn’t set off any alarms. It read:

Dear Good People,

I would very much like to contact Nora Ephron, Movie Director of the movie, “Sleepless in Seattle.” I think she would be interested in what I have to say.

Sincerely, Lyle Christiansen.

When Sherrie Hart, the Sherlock detective commandeering the e-mail in-box at the time, read the note, her eyes rolled. Oh, boy, she thought. Here we go again. She typed back:

We would not be able to give you a famous person’s address. If you want to write a letter to Ms. Ephron, we would deliver it to her ourselves. The fee would be $495. Proceed?

Proceed. When Lyle Christiansen’s money order and letter came in the mail a few days later, Hart passed them on to the agency’s owner, Skipp Porteous. With wavy hair, baggy eyes, and sandals on his feet, Porteous looks more aging hippie than hard-boiled gumshoe. He breaks in the afternoon for a non-tough-guy ritual: meditation. Porteous was once a preacher, but became disenchanted with religion, and in the course of writing a book called Jesus Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, discovered he was good at digging around.

Porteous looked at the envelope. He studied the return address. Morris, Minnesota. He looked at a map. The town was two hours from Fargo, North Dakota. Population: 5,200. He opened the letter, and after peering inside for powders, he read it. It barely made sense. It was a rambling confession of finding the answer to a “famous unsolved caper” that would make a great movie—and one only Ephron could direct, because she had “heart.” She could call this movie Bashful in Seattle—because the main character in the caper lived near Seattle. Skipp thought, Strange, yes; dangerous, no. So he hailed a cab, rode over to Ephron’s building on East 79th, and left the letter with her doorman. Ephron got the letter. She opened it and looked at it and put it down on the kitchen counter. It stayed there for some time. Then it disappeared. “I don’t know what happened to it,” she says.

In Morris, Christiansen was waiting. He is 77 years old, retired from the post office, and now works as an inventor and holds a few patents. Every day, he’d walk out to his mailbox hoping for a reply from Ephron. Nothing came. He sent Sherlock another letter, which Porteous had delivered. Weeks passed. No word. Did she know he was paying all this money to reach her? Finally, Christiansen wrote to Sherlock: “As you know, I have been trying to contact Nora Ephron, but for some reason she doesn’t answer my letters. Now I would like you to help me. I am sitting on the answer to a many decades mystery which has never been solved … No one was killed or injured in the caper but could easily have been … I hope you will think about this and let me know.”

Porteous was curious. He began to probe with e-mails. Christiansen would often type back late at night, he said, so his wife wouldn’t discover his secret relationship with D.B. Cooper. “Yes, I knew the culprit personally,” Lyle wrote one day. “He was my brother.”

The case of D.B. Cooper is one of the most famous crimes in American history. It is also the only skyjacking in the world that has gone unsolved. Over the past three decades, the FBI has investigated nearly 1,000 suspects. They might as well be looking for Sasquatch. D.B. Cooper is folklore now. He’s inspired books, movies, safety regulations for airplanes, and treasure hunters. A bar celebrates the anniversary of his heist with a D.B. Cooper look-alike contest. Poems have been inked. Songs too, like Chuck Brodsky’s “The Ballad of D. B. Cooper”:

It was Thanksgiving eve

Back in 1971

He had on a pair of sunglasses

There wasn’t any sun

He used the name Dan Cooper

When he paid for the flight

That was going to Seattle

On that cold and nasty night

That night changed aviation history. It started in Portland, Oregon, when a man walked up to the flight counter of Northwest Orient Airlines. He was wearing a dark raincoat, dark suit with skinny black tie, and carrying an attaché case. He had perky ears, thin lips, a wide forehead, receding hair. He gave his name, Dan Cooper, and asked for a one-way ticket to Seattle, Flight 305. The ride was a 30-minute puddle jump. He sat in the last row of the plane, 18-C, lit a cigarette, and ordered a bourbon and soda. The plane took off and he passed the stewardess a note.

Florence Schaffner was 23, cute, perky, the sexy stewardess. Working on planes, she’d been approached by so many men that she’d taken to wearing a wig onboard to disguise herself. She dropped the man’s note in a purse, thinking, Just another guy hitting on me. But the man was insistent. “Miss. You’d better look at that note. I have a bomb.” She looked at the man’s eyes. She saw that he was serious.

She read the note. It was printed in felt pen, all capital letters, elegantly formed. “I have a bomb in my briefcase. I want you to sit beside me,” it read. She did as he requested, then asked to see the bomb. She saw a tangle of wires, a battery, and six red sticks. Then he dictated some instructions: “I want $200,000 by 5:00 p.m. In cash. Put in a knapsack. I want two back parachutes and two front parachutes. When we land, I want a fuel truck ready to refuel. No funny stuff or I’ll do the job.” He let her get up to take them to the captain. When she got back, the man was wearing dark sunglasses.

Schaffner’s mind was reeling. She imagined her parents back in Arkansas watching the evening news. She imagined the plane exploding. She imagined this man taking her hard by the wrist and raping her right there. She took deep breaths. Inhale, exhale, repeat. Surprisingly, the man was able to calm her down. He was not a so-called sky pirate, which she’d read about in the papers, or a hardened criminal. He was not a political dissident with a wish to reroute the plane to Cuba, like many of the hijackers until then. He was polite. Well spoken. A gentlemen. At one point, he offered to pay for his drinks with a $20 bill and insisted the stewardess keep the rest ($18) as change. He also seemed like a local, glancing out the window and saying, “Looks like Tacoma down there.”

The plane landed on the Sea-Tac tarmac, greased up by the squalls of the rainstorm. It was late, two hours late, because FBI agents needed time to collect Cooper’s ransom and to station their sharpshooters. Inside the cabin, Cooper ordered all passengers be released. The airline staff then carried his ransom—$200,000 in $20 bills (the bundle weighed 21 pounds) and parachutes—onto the plane as it refueled. The gentleman hijacker was getting anxious. “It shouldn’t take this long,” he said, and told the captain to get the plane back in the air. Where to?

“Mexico City,” he said, and delivered more specific flight instructions: Keep the plane under 10,000 feet, with wing flaps at fifteen degrees, which would put the plane’s speed under 200 knots. He strapped the loads of cash to himself and slipped on two chutes—one in front, one in back—and moved deeper into the vessel, toward the aft stairs, which were used to let passengers disembark from the rear of the plane. The 727 was the only model equipped with such stairs. He lowered them. The seal of the cabin broke, and there was engine noise in his ears and the cold, black, wet windy night outside. He climbed down the stairs and hovered on a plank over southwest Washington. The plane was too high to see anything below. The cloud ceiling that night was 5,000 feet, and some of the most rugged terrain in this country was beneath it: forests of pine and hemlock and spruce, canyons with cougars and bears and lakes and white-water rapids, all spilling out into the Pacific. And then, as the ballad goes,

Out a little service doorway

In the rear of the plane

Cooper jumped into the darkness

Into the freezing rain

They say that with the windchill

It was 69 below

Not much chance that he’d survive

But if he did where did he go?

They did look for him. The Feds scoured the forests the next day, and for days after in a dense fog, praying for a parachute tear, a $20 bill, a body. One team of treasure hunters chartered a submarine and descended hundreds of feet into a lake. In Washington, D.C., at the headquarters of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, agents coordinated a profiling campaign. The name, they soon found, was a fake. But Dan Cooper had already been immortalized as D.B. Cooper. The error happened when a reporter got the wrong first name from a police source and it hit the wires. So what if it was wrong? It sounded good, mythic. It made it seem like Cooper’s jump meant something, and it did. “You know, it’s funny,” said one local resident at the time. “Folks are actually pulling for this man. That’s all anybody wants to talk about. I hear it all day long. ‘Hope he made it, he deserves it, hope he gets away with every nickel.’ Like he’s some kind of Robin Hood character.” He was also anonymous. “He was John Doe. He wasn’t some wild radical … He was you or me or your neighbor.”

The FBI didn’t believe that. There were too many specific traits Cooper needed to pull off the jump. Cooper knew how to parachute, and in tough conditions. Maybe he’d been in the Army. Better yet, they figured, the paratroops. He was also familiar with planes (10,000 feet, fifteen-degree wing flaps) and the area (“Looks like Tacoma down there”). They also knew what Cooper looked like. They had a detailed sketch that Florence Schaffner helped create. And there was his personality. “He seemed rather nice,” said Tina Mucklow, another attendant on the flight. “He was never cruel or nasty. He was thoughtful and calm.”

Suspects came and went. Five months later, Richard McCoy, a former Sunday-school teacher from Utah and a Vietnam helicopter pilot, jumped out of a plane over Utah with a $500,000 ransom. He was snatched by the FBI a few days later with $499,970 in a cardboard box. McCoy told the Feds he wasn’t Cooper, but they didn’t believe him. He was sentenced to 45 years in prison. Then he escaped, using a fake gun made from plaster of Paris stolen from dental supplies, and led a crew of convicts through the prison gates with a garbage truck. When the Feds found him again, there was a shoot-out. McCoy was killed.

In 1980, some of Cooper’s money surfaced. A boy found $5,800 in decomposing twenties buried in a bag, a few feet from a river. The FBI searched the area again, hoping to find more bills—or, better yet, a body. They found nothing.

The next major suspect was Duane Weber. Just before he died in 1995, Weber’s wife claims, he told her, “I’m Dan Cooper.” The Feds eventually collected fingerprints and DNA samples, but the case remains open.

The Cooper file is now a morgue of dead-end leads. It sits buried in the basement of the FBI’s Seattle field office and occupies several shelves in long rows that open and close by spinning black plastic wheels. The belief among agents handling the case now is that Cooper died in the jump—the conditions were simply too brutal to survive, and the twenties would have blown away. When a new tip arrives in the mail, the Feds typically shrug it off and file it away.

One of those tips that came in was from Lyle Christiansen. In fact, he claims he told the FBI about his older brother several times. “Dear Good People,” a copy of one of his letters, written in November 2003, begins. “Here’s the story of how I began to suspect my brother was D.B. Cooper.” He was watching TV one night, he told them, and flipped on the show Unsolved Mysteries, which had an episode about the Cooper case. “I sat up in my chair,” he wrote, “because my brother was a dead ringer to the composite sketch of D.B.” Suspicious, he read up on the case. “There was so many circumstances that I became convinced my brother was truly D.B. Cooper!”

“I’m not getting any younger,” Christiansen wrote to the FBI again, and for the final time, in January 2004. “Before I die I would like to find out if my brother was D.B. Cooper. From what I know I feel that he was and without a doubt.”

A relative of D.B. Cooper’s! Skipp Porteous couldn’t believe what three decades of federal agents (and Nora Ephron) had missed. This would be the biggest case of his career. He could barely contain himself as he typed back to Christiansen: “This is potentially a very hot story.” He wanted facts. Basic stuff: full name, age, Social, address. Lyle wrote back later that night: “Kenneth Peter Christiansen; Born Oct. 17, 1926, deceased July 30, 1994 from cancer. Lived in his own home in Bonney Lake, WA. One could see Mt. Rainier from there. So. Security #473 30 3599. He retired from NWA as a purser. His employee #33983.”

Lyle also dropped a few photos and documents in the mail, and began to tell Skipp about his family. They grew up on a farm with cows and pigs and tractors and chickens. This was during the dust bowls of the Great Depression. “All of us kids did not get lots of hugs when we were growing up and we missed a lot because of it,” Lyle says. “I think it made us all a little bashful and made us long for the hugs. Our folks were so busy. Pa in the field and Ma, cooking, sewing, washing clothes, canning, gardening, and also helping with the harvesting.” For fun, they went to the county fair, where his father once took on a prizefighter and earned $100 by lasting one full round. Lyle and Kenny watched as their dad was paid out in five $20 bills. Kenny could never forget those $20 bills, Lyle says. “That was a lot of money during the Great Depression.” Their father also invented things. One was “a contraption that was supposed to work as a [perpetual] motion machine,” Lyle remembers. It was made from wood and ran on marbles.

Growing up, Lyle was different from Kenny. Lyle was into contact sports and girls. Kenny was into “classy things,” Lyle says. Kenny was so precise in his drawings that he composed illustrations for the yearbook staff. He played cornet in the band and sang in the men’s chorus. He danced tap. And acted in several school plays. And in sports, Kenny set school records for the half-mile. In high school, he was at the top of his class and had his pick of twelve private colleges. But the war was on, it was 1944, and Kenny enlisted. He thought of the Air Force, but decided on the Army, and chose an elite, dangerous, and thus better-paying specialty: the paratroops. “Kenny was always looking for ways to make a buck,” Lyle says.

Training was brutal. By the time Kenny had strapped on all his gear—which could include parachute and reserve chute, helmet, canteen, cartridge belt, compass, gloves, flares, message book, hand grenades, machete, M-1 Garand rifle, .45 caliber Colt, radio batteries, wire cutters, rations, shaving kit, instant coffee, bouillon cubes, candy—the entire bundle weighed as much as 90 pounds. The paratroops donned such heavy gear (they had to survive behind enemy lines for weeks) they couldn’t walk onto the transport planes on their own. They had to be pushed on.

Jumps were also menacing. The quality of the parachutes was primitive. You could not steer them out of the way of power lines or trees. You hit the ground hard on your boots, buckling the ankles and the knees, in some cases breaking them. Kenny trained with the 11th Airborne Division, the Angels, which had been sent to the Pacific. But he never saw combat. When he was finally deployed, on August 16, 1945, his discharge papers show, the war was over. He ended up in Japan, joining the initial occupation forces. He ran the mail room and made jumps on the side for extra money.

“Dear Folks,” Kenny wrote home in one letter dated August 4, 1946, from Sendai. “I went to church this morning. I went last Sunday also. I had more reason to go last Sunday, as after ten months of hibernation, I once again donned a chute and reserve and entered a C-46. I cringed a good deal, but I managed once again to pitch myself into the blast. That jump was worth $150. The nicest thing about the whole affair was that I never had time to worry about it … Don’t get the idea that I didn’t get that certain stomackless [sic] feeling, because I did.”

After that jump, he vacationed in Namazu, a fishing village south of Tokyo. “I spent most of my time up on the roof during the day; nights I usually lounged in a beach chair down by the water’s edge,” he wrote. “They had a group of Hawaiian guitar players down there. With the music, the breeze off the Ocean, and the waves crashing the shore, I felt like a millionaire enjoying his millions.”

“There is something you should know, but I cannot tell you,” Kenny Christiansen told his brother on his deathbed.

Porteous couldn’t believe it. The profile that was coming into focus was remarkably exact. The paratroops? That’s exactly the kind of jumper the Feds were looking for. Not an expert who knew fancy equipment. A gutsy amateur who only specified “front” chutes and “back” chutes. He wanted to know more about Kenny. “This is fascinating stuff,” he wrote Lyle, who then told him about all the odd and dangerous jobs Kenny did for extra pay. After college, Lyle said, his brother went back to the Pacific, this time to Bikini atoll, in the Marshall Islands. The government was testing nuclear bombs there. Kenny worked as a telephone operator. It was lonely, though he liked being alone, and it was always beach weather on Bikini. Kenny loved the beach, Lyle said. Even back home, he saved to spend on travel. In college, he took a job selling magazine subscriptions on the road. He traveled once with a carnival, selling tickets. Then he’d leave for warmer climes: Jamaica, Laguna Beach, L.A., Mexico City. Then Kenny learned of a job working for the airlines.

Northwest, based in Minneapolis, was looking to hire technicians to work on its planes in Shemya, an island in the Aleutians. He started as a mechanic and was rehired in 1956, as a flight attendant. He relocated to southwest Washington and was promoted to purser. This meant $50 extra monthly pay, and dealing with Customs and Immigration agents and managing the plane’s money.

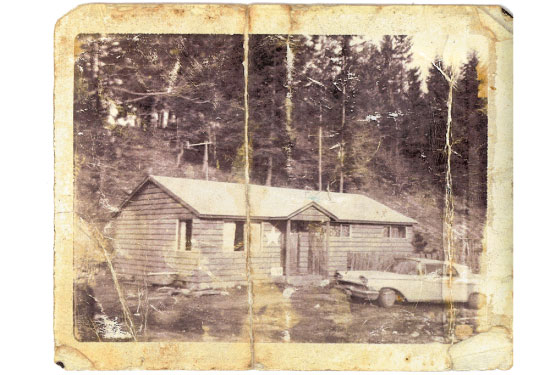

According to property records, Kenny was able to purchase a house and some land. In October 1972, about a year after Cooper’s jump, Kenny paid $14,000 for a modest ranch in Bonney Lake, a small mountain town, in the Cascades. A year later, a deed shows he paid $1,500 for a parcel of land.

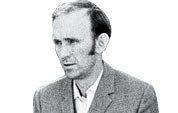

“He was almost invisible,” says Harry Honda, a Northwest purser who worked with Kenny. “If you asked somebody on his plane who was the purser on that flight, they couldn’t tell you—that’s how quiet this guy was.” If they had a layover, Kenny would not go out with the staff. “He was noncommunicative,” says Mary Patricia Laffey Inman, a Northwest purser. “He kept to himself. He was a plaid-shirt guy,” says Lyle Gehring, another Northwest purser, who worked alongside Kenny for years. “You ask people and say ‘Ken Christiansen,’ they say, ‘Who?’”

At home, he always wore the same clothes: denim overalls and a blue-striped railroad cap. “He looked like a farmer, you know,” says Rose Edmiston, a former Northwest flight attendant who lives in Bonney Lake. “That would probably be the last person in the world I would think could be D.B. Cooper.” Driving around town, she’d sometimes see him with younger men in front of his house, scrubbing down a car with soap or working under the hood. The rumors she heard about him were true: He was taking in troubled kids and runaways. One, she heard, he found sleeping in the town laundromat. Another kid was Kenneth McWilliams, or Mac, who lived with Kenny off and on for twenty years.

“He was an amusing character,” McWilliams says now of Kenny. He describes life in the house as “odd.” There were always other men around, men from the Army whom Kenny knew and had relationships with. “It was uncomfortable to me, because I’m not like that, but not everybody lived in that house at night,” McWilliams says. Living there as a teenager was also liberating. When Kenny came back from Japan or Germany, there were always gifts: expensive food, big bottles of aged sake, ceramic dolls. Kenny never held back financially. They always ate out. “Any restaurant, really,” McWilliams says. “He’d always call it ‘my turn.’ He’d never accept that I pay for some of the things that he ate.” Kenny also helped Mac and other young men who lived with them learn how to save. Once, as a teenager, McWilliams says, he wanted to buy a car. Kenny opened up a bank account for him and matched every dollar he earned. “There was always a little bit of cash, maybe a little bit in his dresser. Also in his wallet.” He thinks it’s possible Kenny was D.B. “As a steward, they made good money, but they didn’t make that much money.”

Northwest’s salaries were notoriously meager. For pursers, the saying was “$212 a month and all you can carry,” and that meant stealing toilet paper from the airplanes’ bathrooms to supplement your paycheck. Female flight attendants were forced to adhere to strict intercompany mandates, like weight checks. They also couldn’t wear glasses. Or have their own rooms during layovers. Men could. All of which created an atmosphere of hostility toward Northwest. Workers would strike. Workers sued. Kenny was never vocal in his outrage toward Northwest, “He’d always just sit in the back at a union meeting, or not [go] at all,” says Gehring. Quietly, Kenny hated the strikes because it meant he had to find quick work, like picking apples on a farm. “He built up a little hatred for NWA for laying people off and forcing them to go on strike,” according to Kenny’s brother. “I think he thought he could sock it to them by pulling off the hijacking.”

When the package of photos from Morris arrived in the mail, Skipp looked at Kenny Christiansen for the first time. “It was uncanny, really,” Skipp says. “He looked just like the sketch.” He had more questions for his brother. Did Kenny ever make extravagant purchases? Only his house and some land, Lyle said. Did Kenny drink bourbon? Yes, Lyle said. Kenny loved bourbon so much he collected bourbon bottles. Did he smoke? Yes. It all added up. There was a wealth of detail, a full portrait of a man who possessed so many of Cooper’s traits—a polite, quiet paratrooper with a secret life.

Still, there was no concrete testimony, nothing direct. Then Lyle told him about a conversation he had with Kenny when his brother got sick with cancer. Lyle suspected the cause was radiation he’d suffered at Bikini atoll. On his deathbed, Lyle remembers, his older brother pulled him close. He then said something that didn’t make sense to him then. It does so now.

Kenny said, “There is something you should know, but I cannot tell you!”

Lyle didn’t want to know. “I don’t care what it is you cannot tell me about. We all love you.”

One of the only living eyewitnesses to the Cooper case is Florence Schaffner, the stewardess who accepted Cooper’s note. She now lives in Lexington, South Carolina. One Sunday last month, we had lunch at Lizard’s Thicket, a local chain in Columbia that serves fried chicken for brunch.

Flo, as she calls herself, has frosted blonde hair and deeply tanned skin. Her hands were shaking on the table. Just thinking about the Cooper case makes her nervous, she said. She was never the same after Cooper’s jump. She took a month off and went to live with her family back in Arkansas. She also became paranoid. If Cooper was living, she feared that he’d come after her. Eliminate the witness, you know. She’d look under her car for bombs. She’d turn her keys over real slow.

Over the years, the FBI has shown her photos of dozens of suspects, and she has yet to identify any of them. I’d brought the photos of Kenny Christiansen, and she spread them on the table. She zeroed in on the passport photo all blown up. She rubbed his features on the page. “The ears, the ears are right.” She moved to the lips. “Yes, thin lips. And the top lip, kind of like this, yes.” Then the forehead. “A wide forehead, yes.” Then the hair. “Receding, yes, the two areas—yes, yes—sort of like this.” She was pushing down on the photo hard now, rubbing the image like a charcoal drawing. “There was more hair, though.” The eyes. “About like that.” The eyebrows. “Yeah, about like that.” The images were closer in resemblance to Cooper than any of the suspects she’s ever seen, she said. But? “But I can’t say ‘Yay.’” We got up from the table. “I think you might be onto something here,” she said.

The definitive expert on the Cooper case is Ralph Himmelsbach. He was the FBI’s lead agent on the hijacking for eight years. He’s now retired and lives on a farm in Woodburn, Oregon. He’s got a metallic white mustache trimmed just so and bushy eyebrows that curl into a wave. I wanted to see what he thought of Kenny as a suspect, and one afternoon this summer we sat outside on his patio. A plane passed by. “It’s an AT-6 Texan,” Himmelsbach said, looking up. “A North American AT-6.” Himmelsbach knows planes and lives to fly. I asked him if he’d ever investigated anybody who worked for Northwest Airlines. “No,” he said, and explained. “We had an awful lot of suggestions by people that said ‘I think it’s an inside job.’ It is inconceivable for several reasons. The most obvious, if you know anything about airline procedure, is that it is not possible for a conspiracy to form because the individuals are not in charge of what flights they’re going to go on.” But what about a lone employee? Himmelsbach ruled this out too. “If you were acquainted as I was with many of the people in the airline industry,” he explained, “they are exceptional people. They are head and shoulders above the standards and the values and the character of normal, average Americans.”

I pulled out photos of Kenny. He studied them slowly.

“Not bad,” he said. “Except for the hair.”

I then showed him Kenny’s discharge papers from the Army. He looked at Kenny’s height (five-eight), weight (150 pounds), and eye color (hazel), then pushed the papers back. “Well, he’s too short, not heavy enough, and has got the wrong color eyes.” I then told him about Kenny’s history: his service in the paratroops, and working for Northwest—as a purser, a flight attendant, a mechanic—and living near Sea-Tac, and his quiet mien. The old man lit up like somebody had plugged him into the wall socket. “All of this makes him look like a good suspect to me,” he said. “If I was still on duty and it were up to me, I’d say, ‘This guy is a ‘must investigate.’”

My next stop was Bonney Lake. I wanted to see Kenny’s house out there. On the drive north from Portland, it became clear why so many agents believed that Cooper never survived the jump. The trees are hundreds of feet tall in the Cascades, a snow-capped collection of volcanoes and glaciers and miles of snowfields that never melt. Mount Rainer is the centerpiece, sitting high at over 14,000 feet, watching.

Kenny’s place is now a print shop on the main drag. I parked in the back and looked at Mount Rainier. It looked, just as Lyle said, “like it was across the street.” The shop was closed. I peered through the dark windows. I tried to imagine Kenny in there. In his purser’s uniform, getting home from another trip to Tokyo, with the young runaways he housed. I tried to imagine where the kitchen was. Lyle said he hung a poster there for inspiration.

THERE ARE THREE KINDS OF PEOPLE, the poster read.

Those who MAKE things happen.

Those who WATCH things happen.

And those who WONDER what happened.

And I wondered myself: Which one was Ken Christiansen?

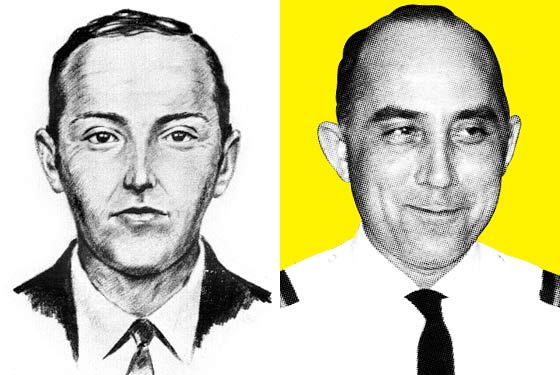

THE WITNESS

Florence Schaffner

The flight attendant who received the note.

THE OTHER D.B. COOPERS

Richard McCoy

Suspected of being D.B. Cooper after committing a different skyjacking.

Duane Weber

Suspected posthumously; he professed to his wife on his deathbed that he was D.B. Cooper.

Photographs: From top, Bettmann/Corbis (2)

SEE ALSO:

D.B. Cooper: A Timeline