Vietnamese language in the United States

| Vietnamese | |

|---|---|

| Vietnamese language in the United States | |

| Tiếng Việt tại Hoa Kỳ | |

A bilingual English–Vietnamese sign welcomes visitors to Little Saigon in Garden Grove, California. | |

| Native to | United States |

| Ethnicity | Vietnamese Americans |

| Speakers | 1.6 million (2019)[1] |

Austroasiatic

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin (Vietnamese alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | vi |

| ISO 639-2 | vie[2] |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | vi-US |

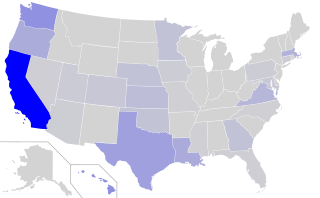

Distribution of Vietnamese in the United States according to the 2000 United States census. | |

Vietnamese has more than 1.5 million speakers in the United States, where it is the sixth-most spoken language. The United States also ranks second among countries and territories with the most Vietnamese speakers, behind Vietnam. The Vietnamese language became prevalent after the conclusion of the Vietnam War in 1975, when many refugees from Vietnam came to the United States. It is used in many aspects of life, including media, commerce, and administration. In several states, it is the third-most spoken language, behind English and Spanish. To maintain the language for later generations, Vietnamese speakers have established many language centers and coordinated with public school systems to teach Vietnamese to students who are born and raised in the United States.

After several decades of development in a multilingual environment independent of the native country, Vietnamese in the United States has some differences from the Vietnamese language currently spoken in Vietnam, and the community of Vietnamese speakers has consciously tried to preserve those differences.

History

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 3,000 | — |

| 1980 | 197,588 | +6486.3% |

| 1990 | 507,069 | +156.6% |

| 2000 | 1,009,627 | +99.1% |

| 2010 | 1,427,194 | +41.4% |

| 2019 | 1,570,526 | +10.0% |

| Source: [3][4][5][1] | ||

The history of Vietnamese in the United States is fairly short and intimately connected to the presence of Vietnamese people in this country. Prior to World War II, Southeast Asian languages were virtually unknown in the US. At that time, Indochina was a French colony, so research on the Vietnamese language was primarily conducted by French scholars.[6] In the 1950s, schools such as Cornell, Columbia, Yale, and Georgetown, as well as the Foreign Service Institute of the Department of State, brought the language into their curricula. In 1954, the Army Language School began to teach Vietnamese in the military.[7]

In 1969, there were about only 3000 Vietnamese people in the entire United States, including wives of American servicemen who served in Vietnam. As the Vietnam War deteriorated, the number of Vietnamese people gradually increased. By the early 1970s, there were 15,000 Vietnamese; this number doubled to 30,000 by 1975. Following Operation New Life, the number of Vietnamese people in the US drastically increased.[8]

In 1978, Người Việt, the first Vietnamese-language daily newspaper in the United States, began publication in Orange County, California. The newspaper helped to bring news from the homeland to the refugee community, and helped them prepare for a new life in the United States.[9]

In 1980, Vietnamese had 200,000 speakers and was the 14th-most spoken language in the US. From 1980 to 2010, Vietnamese was the fastest-growing language in the United States, having increased sevenfold.[10] By 2010, Vietnamese had surpassed many other languages to become the sixth-most spoken language (behind English, Spanish, Chinese, French, and Tagalog).[11]

In the early 21st century, Vietnamese began to show signs of losing its hold on new generations of Vietnamese Americans who are born and raised in the United States and having limited connections to Vietnam. Vietnamese is still maintained among recent immigrants while more than 90% of third-generation Vietnamese Americans only speak English. However, only 20% of second-generation Vietnamese Americans entirely use English, compared to 46.8% in the first generation. This shows that there are efforts to preserve the language among Vietnamese speakers.[12] Additionally, there are efforts among Vietnamese Americans to bring the language to public school curricula so that their children do not forget their heritage language.[13][14]

Demographics

Distribution

| Birthplace | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vietnam | 87.4 | 82.0 | 79.7 | 74.3 | 71.4 |

| US | 7.0 | 13.3 | 17.1 | 22.7 | 23.5 |

| Other | 5.5 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 5.0 |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Vietnamese speakers are primarily ethnically Vietnamese, so the language is most spoken in places with a high presence of Vietnamese Americans. In 2019, it was estimated that 71.4% of Vietnamese speakers were born in Vietnam, 23.5% in the US or its territories, and the remaining 5% born in another country.[15]

In four states (Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas, Washington), Vietnamese is the third-most spoken language, behind English and Spanish.[16] It has a strong presence in the West Coast, with 40% of speakers living in California, while Washington has the third-highest number of speakers. Vietnamese has a limited presence in larger cities; they have higher concentrations in the suburbs rather than in the inner cities.[8]

Fluency

| Generation | Definition | % 1980[17] | % 2006[17] | % 2019[18] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Born outside the US | 95 | 77 | 60 |

| 2 | Born in the US | 3 | 19 | 40 |

| 3 | Born in the US and having one parent born in the US | 2 | 4 |

The fluency of the language among Vietnamese Americans is divided by generation. The first generation is defined as those born outside the United States (mainly Vietnam), the second generation are those who are born in the United States, while the third generation consist of those born in the United States and having at least one parent born in the United States. In 1980, 95% of Vietnamese Americans belong to the first generation, 3% in the second generation, and 2% in the third generation. By 2006, the first generation decreased to 77% while the second increased to 19%, the third generation still at a modest 4%.[17] According to US Census Bureau estimates, by 2019 the percentage of foreign-born Vietnamese Americans decreased to 60.3% while those who are born in the US increased to 39.7%. Among those 5 and older, 22.3% only used English at home, while the remaining 77.7% used other languages (primarily Vietnamese) — among those 44.0% don't have a good command of English.[18]

| Language ability | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minors | Total | Minors | Total | Minors | Total | Minors | Total | |

| Vietnamese only | 1.1 | 7.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 5.5 |

| English not well | 6.5 | 28.7 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 5.5 | 23.3 |

| English well | 18.7 | 32.2 | 15.5 | 14.9 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 15.0 | 27.7 |

| English very well | 26.9 | 25.7 | 58.3 | 60.8 | 6.0 | 7.1 | 41.5 | 31.6 |

| English only | 46.8 | 6.4 | 19.9 | 18.1 | 91.3 | 90.2 | 37.5 | 11.8 |

Research in 1998 by Min Zhou and Carl Bankston showed that Vietnamese is maintained when it is used at home and in the community. From 1980 to 2006, the percentage of Vietnamese Americans who do not use Vietnamese at home (only speaking English) increased modestly (from 9.4% to 11.8%) while the percentage of those who speak English "very well" while still able to speak Vietnamese increased considerably (from 20.6% to 31.6%). This indicates a trend consistent with language assimilation theories — Vietnamese immigrants adopting English while maintaining fluency in their native language.[12]

However, there are signs that English is increasingly replacing Vietnamese among young people (under 21). In the first and second generations, about 46.8% and 19.9% respectively no longer use Vietnamese; in the third generation, while currently a small percentage of the total, more than 90% use English exclusively.[12]

Usage

While not as well known as Spanish or some other European languages, Vietnamese maintains a presence in some aspects of public life. In the media and creative arts, it is mainly used among the Vietnamese American community. It also has a small presence in commerce and administration. Most DMVs provide Vietnamese-language driving instructions, and some states even allow the test to be partly taken in Vietnamese. Vietnamese is an elective subject in many colleges and universities, and is seen less often in high schools.[17]

Media

Most Vietnamese language media are published in metropolitan areas with high concentration of Vietnamese people. While small in comparison to English or Spanish language media, Vietnamese language media have flourished in the US.[19]

Published since the late 1970s, Người Việt from Southern California is the largest Vietnamese language newspaper in the United States. From 1999 to 2005, the San Jose Mercury News published a Vietnamese edition named Viet Mercury.[19] After the Viet Mercury ceased publication, two other newspapers replaced it in Northern California: Việt Tribune và VTimes.[19][20] Early newspapers focused on local news for Vietnamese Americans; later they expanded to serving other readers. Người Việt has an English edition for Vietnamese Americans born in the US. Besides these publications, other publications in many other languages are also in circulation in the Vietnamese American community.[19]

There are two Vietnamese language radio stations broadcasting in Greater Los Angeles (KALI-FM and KVNR).[21] Little Saigon Radio was formed in 1993, broadcasts in the three areas with large Vietnamese American populations including Southern California, San Jose, and Houston. In additional to locally produced shows, the station also rebroadcast Vietnamese-language programs from international broadcasters such as BBC and RFI.[22] Radio Saigon Houston was cited as helping to attract Vietnamese people from California to resettle in Houston when they hear its programming rebroadcast in California.[23]

Television stations include Saigon Broadcasting Television Network (SBTN) heardquartered in Garden Grove, the first Vietnamese-language TV station broadcasting 24 hours a day via cable and satellite nationwide since 2002. SBTN attracts a wide variety of audience in its diverse programming, including news, theatrical films, drama, documentaries, variety shows, talk shows, and children's shows.[21] Besides SBTN, there is also VietFace TV owned by Thúy Nga Productions, also broadcasting 24 hours a day in Orange County and nationwide via DirecTV;[24][21] and Vietnam America Television (VNA/TV) broadcasting in Southern California, San Jose, and Houston with an anti-communist platform and committed to not showing programs produced in Vietnam.[25] These and other networks are broadcast over the air on digital subchannels of television stations in large cities, such as KSCZ-LD in San Jose. Outside of California, Viet-Nam Public Television (VPTV) headquartered in Falls Church, Virginia serve the Washington, DC area. Some localities also have Vietnamese language programming on public access television.[19] VTV4, the international broadcasting arm of the Vietnamese state-owned Vietnam Television, was once broadcast via satellite in the US, but was deemed "boring"; its main audience consists of international students or recent immigrants from Vietnam.[26] VTV4 stopped broadcasting via satellite since 2018.[27]

During the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 elections, fake news became an issue in the Vietnamese-speaking community, especially among the elderly who are not well-versed in English and do not consume mainstream media.[28] In response to the proliferation of fake news, some younger Vietnamese Americans who are fluent in both English and Vietnamese formed groups with the aim to challenge the fake news and bring accurate news in Vietnamese to the community, including Viet Fact Check, VietCOVID.org, and The Intepreter.[29][30]

Arts and literature

After 1975, many artists, writers, and intellectuals from South Vietnam left the reunified country under communist rule and moved to the US. In the beginning, Vietnamese-language literature published in the US revolved around themes of nostalgia for the past, the feeling of guilt for those who stayed, and exile.[31] The early writers criticized American values such as material pursuit as well as social and moral values.[32] With the arrival of Vietnamese boat people since 1977, Vietnamese literature in the US changed themes to wrath and agony; these new writers left Vietnam with a clear ideological purpose: to seek freedom and to tell the world about the "Vietnam in blood and tears".[33] These themes are not only manifested in literature; in music and art the boat people composed works full of misery and anger. Hundreds of magazines and newspapers and books were published in Vietnamese with the aim to alert the world about the ordeal of the boat people. In contrast to the nostalgic works of earlier writers, the works of boat people authors paint a picture of Communist Vietnam as hell on earth full of human misery and agony.[33]

In music and arts, Vietnamese refugees began to build structures for media and entertainment as soon as they began resettling in the US. In the beginning, refugee musicians recorded and distributed music cassettes reflecting their exile status, strongly critiquing the communist government while also bringing their audience melodies that bring back to a time of peace. In contrast to immigrants from other countries, Vietnamese exiles strongly reject cultural productions that originate from their homeland now under communism.[34] In the beginning, Vietnamese Americans watch dubbed Hong Kong and Taiwanese films via VHS for their entertainment needs. Starting from the 1980s and 1990s, the variety show Paris by Night by Thúy Nga Productions became a connecting bridge between the various Vietnamese communities around the world.[34] The early production titles reflect themes related to exile, like Giã Biệt Sài Gòn (Farewell to Saigon), Giọt Nước Mắt Cho Việt Nam (A Drop of Tear for Vietnam), with anti-communist content as the guiding principle to attract audiences.[35] With the changing tastes of the audience as they assimilate into American society, later programs shifted themes away from politics and towards contemporary American culture.[35] After the success of Paris by Night, other similar productions soon followed suit, such as Asia Entertainment, Vân Sơn Productions, and Hollywood Night.[34] By 2008, Little Saigon in Orange County, California was the largest Vietnamese-language production center in the world, dwarfing Vietnam by a factor of 10.[36]

Genres of Vietnamese music performed in the US include folk music, cải lương, đờn ca tài tử, pop, etc. Because most Vietnamese people in the United States came from the South, these genres originated from southern Vietnam.[37] Cải lương composers continue to create new works, while mobile theatrical troupes perform nationwide. In larger Vietnamese communities, pop music predominates.[37]

Since 1991, the Vietnamese American Arts & Letters Association (VAALA) worked to assist Southeast Asian artists, especially focusing on Vietnamese literature and arts. VAALA has organized the Vietnamese International Film Festival annually since 2003, showcasing creative works made by or are about Vietnamese people.[38]

Additionally, many Vietnamese American authors achieved success in the mainstream American literary scene, primarily with English-language works describing the experience of Vietnamese people in the United States. They include Viet Thanh Nguyen who received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the poet Ocean Vuong who received the MacArthur Fellowship, journalist Andrew Lam, writer Le Ly Hayslip, and cartoonist Trung Le Nguyen. Although their works were written in English, the authors include in them some Vietnamese vocabulary and cite the influence of their native language in their diction and syntax.[39]

Commerce

In Little Saigon, Orange County, California, Vietnamese is ubiquitous: it can be found in signage in front of offices, stores, cemeteries, on billboards advertising companies such as Toyota and McDonald's, and even on bus advertising.[40] Many stores and offices in the area serve a primarily Vietnamese clientele, so they use Vietnamese. In a survey among the Vietnamese American community in the Greater Los Angeles area, more than 50% of first-generation immigrants indicate that they use Vietnamese in their place of work, while the proportions for the 1.5 and 2nd generation are 25–30% and 50%, respectively.[41]

Vietnamese people have a large presence in the nail salon industry in the US. In 1987, there were 3,900 Vietnamese nail technicians; this increased to 39,600 in 2002. Vietnamese people account for about 40% of those in this profession nationwide.[42] In California, they account for about 59–80% of workers, and applicants can take tests in Vietnamese to receive their license.[43] In cities with a large presence of Vietnamese people, there are also classes teaching this profession to newly arrived immigrants. In a survey in 2007 among Vietnamese-owned nail salons, 70% of technicians prefer to read publications in Vietnamese. The existence of a large support network in the Vietnamese language for nail technicians in turns attract even more Vietnamese people into this profession.[44]

At many locales in the US, Vietnamese American small business owners form Vietnamese American Chambers of Commerce to support each other and provide training for companies seeking to conduct business in Vietnam.[45] In San Jose, the Silicon Valley Small Business Development Center opened an office to serve local Vietnamese-speaking small business owners with resources in Vietnamese to help them navigate bureaucracy, new technologies and market expansion.[46]

Government and politics

As one of the largest immigrant languages, Vietnamese is used in government, especially in areas related to immigration. In the federal government, since 2000 Vietnamese has been one of six languages used in forms people can fill in for the census. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, amended in 2006, requires that state and local governments provide voting material to assist voters who speak minority languages if they are more than 5% of the voting population in a voting district, or if there are more than 10,000 citizens of voting age who do not have the English skills necessary to participate in the voting process. Accordingly, as of 2021 there are 12 voting areas nationwide where Vietnamese-language voting materials must be made available (including six counties in California, a town in Massachusetts, three counties in Texas, a county in Virginia and a county in Washington).[47] Additionally, many federal agencies also provide materials in Vietnamese to serve people who are not proficient in English, such as the Internal Revenue Service.[48]

| State | Administrative unit |

|---|---|

| California | Counties: Alameda, Los Angeles, Orange, Sacramento, San Diego, Santa Clara |

| Massachusetts | Town: Randolph |

| Texas | Counties: Dallas, Harris, Tarrant |

| Virginia | County: Fairfax |

| Washington | County: King |

At the state level, most departments of motor vehicles provide informational literature in Vietnamese and some offer part of the driving test in Vietnamese.[17] In California, the Dymally–Alatorre Bilingual Services Act require government agencies to provide reading material for languages used by at least 5% of the public being served, so Vietnamese is often one of the offered languages.[49]

At the local level, many areas with a large presence of Vietnamese people have programs providing assistance in Vietnamese. In San Jose, the Vietnamese American Service Center (VASC) was inaugurated in 2022 aiming to provide health and social services to more than 220,000 Vietnamese people in Santa Clara County.[50] Some local agencies do not have Vietnamese language translations available but have personnel to translate when needed, such as via phone.[51]

Politicians in California have sparred over campaign advertising airtime on Vietnamese-language radio and television programs.[52][53]

Education

Researchers found a correlation between Vietnamese language ability and school performance among Vietnamese American students. A 1995 survey among Vietnamese high school students in New Orleans showed students with higher Vietnamese fluency had better academic achievements even though their schooling was primarily in English.[54] According to Bankston and Zhou, the students' Vietnamese language ability is connected to their ethnic self-identification, which was connected to adults in the social group, which in turn provide a support network for the students, promoting academic achievement. These results showed that parents enrolling their children in Vietnamese language schools will not only improve their Vietnamese language ability, but also their academic achievements.[54]

Vietnamese language community schools

Vietnamese language schools started to appear from the end of the 1970s. Classes were usually conducted in churches, Buddhist temples, and other similar locations during the weekends. These schools were usually staffed by volunteers, and they were usually provided for free or charged only a nominal fee.[55]

In 1998, there were about 8,000 students enrolled in 55 community language schools throughout Southern California.[55] According to a survey by the Vietnamese government, in 2009 there were more than 200 institutions or centers teaching Vietnamese, each with between 100 and 1000 enrolled students. In California, there were 16,000 students enrolled in the 86–90 centers, with about 1,600 teachers.[56] The Union of Overseas Vietnamese Language Schools (TAVIET), formerly the Union of Vietnamese Language Centers of Southern California, counts among its members about 100 Vietnamese language schools in Southern California.[14] These schools coordinate to create a common curriculum and to create a common textbook, instead of using textbooks published in Vietnam.[14] Textbooks created by TAVIET include Sổ Tay Chính Tả (a grammar book), the eight-volume Giáo Khoa Việt Ngữ for students in kindergarten to 7th grade, and the five-volume Sử Việt Bằng Tranh (Vietnamese History through Pictures). The textbooks produced by TAVIET are also used in some public school districts in California in their dual-language immersion programs.[57] In addition, the National Language Center for Asian Languages (NRCAL) at California State University, Fullerton also develops teaching materials based on Vietnamese-American experiences, are more culturally sensitive and in accordance with community needs.[14]

In a survey among the Vietnamese American community in Southern California, while only 25% of those from the first generation send their children to Vietnamese language schools, this doubled to 50% in the 1.5 generation and second generation.[58]

Mainstream schools

From 1998 to 2016, bilingual education in California encountered difficulties due to a ban passed by voters.[59] It wasn't until 2016, after voters repealed the ban, that bilingual education was allowed to flourish. In some school districts with a large Vietnamese American presence, many schools established bilingual classes in English and Vietnamese, principally at the primary level. In the 2016–2017 school year, 4 school districts nationwide had bilingual Vietnamese-English programs: Westminster School District in California, Austin Independent School District in Texas, Portland School District in Oregon, and Highline Public Schools in King County, Washington.[13] In Austin, officials were considering more classes for middle and high school students.[60] Students enrolled in these programs are primarily ethnically Vietnamese, but there are those from other ethnicities as well.[13][60][61] In Westminster, the district coordinated with CSU Fullerton to develop the curriculum.[61] By 2021, the programs had spread further, especially in the two areas with high concentration of Vietnamese people in San Jose (Alum Rock and Franklin–McKinley school districts)[62] and Orange County in California.[14]

Outside of primary and secondary schools, some colleges and universities also have Vietnamese language classes as well as classes teaching Vietnamese history, literature, and culture.[14] Efforts to bring Vietnamese language courses to universities were successful in schools such as Harvard, Michigan State, Cornell, UT Austin, UC Berkeley, UCLA, UCSD, Arizona State, and the University of Colorado. At UCSD, students were successful in maintaining the program through community contributions after budget shortfalls threatened the program. In addition, about 300 instructors are trained annually at CSU Long Beach.[63]

Role of the Vietnamese government

In a 2004 interview with VnExpress, Tôn Nữ Thị Ninh, then the deputy chairwoman of the Foreign Relations Committee of the National Assembly, answered a question about "individuals and organizations teaching Vietnamese to overseas Vietnamese people, without waiting for a project from the State":

If our State doesn't create favorable conditions to teach Vietnamese to overseas Vietnamese people, two things will happen. The first is the next generation will lose their Vietnamese roots entirely, and know nothing about the culture and language of the place they were born. The second is that now in many places, reactionary elements also organize Vietnamese classes. Some Việt kiều parents who don't want their children to lose Vietnamese resign themselves to shutting their eyes and let their children go to these classes only to have politics brought in.

For many years, the Vietnamese government had plans to send language teachers to diasporic communities; in 2004, the Politburo launched a project to spend US$500,000 to send language teachers from Vietnam to work overseas "where it is possible". This project was aimed at researching the status of language teaching in overseas Vietnamese communities, building syllabi, publishing study materials and organizing classes in community and cultural centers. However, there were reportedly some difficulties in spending money, due to the prospect that any Vietnamese language school in a refugee community in the West funded by the Communist Vietnamese government will be immediately boycotted and picketed.[66] Officials have approached Vietnamese academics overseas to offer financial support to develop syllabi and organize classes. These classes were planned to provide "neutral" language learning materials to "update" the "old-fashioned" Vietnamese spoken overseas, provide some professionalism to the classroom and create a forum free of politics, in contrast to the community language classes. However, with the difficulties associated with bringing government-supported teaching materials into diasporic communities, these plans were only possible via electronic means (through the Internet and satellite TV).[66]

In 2010, the US was one of six countries in a pilot government project to teach Vietnamese to overseas Vietnamese. In an interview, a government representative stated that one of the challenges for "those who participate in maintaining Vietnamese among generations of Vietnamese overseas" is "the competition for influence among external Vietnamese language teaching centers".[67]

Since 2005, the Vietnamese government began to compile the curriculum for teaching Vietnamese to overseas Vietnamese people. In 2016, the Ministry of Education and Training published two books, Tiếng Việt vui and Quê Việt for this purpose.[68]

The use of Vietnamese government-produced teaching material in the classroom was rejected by most of the Vietnamese community in the United States, particularly the refugees who fled Vietnam to escape communist rule. Those who are opposed contend that Vietnamese government-produced materials are not appropriate for Vietnamese American students, and do not fulfill the needs of parents in teaching their children why they left their country of origin.[69] In 2015, the mayor of Westminster Tri Ta voiced concerns about a textbook widely used in public schools in the United States, in which terms that are only used inside Vietnam (such as "đăng ký hộ khẩu" - family registration and "đăng ký kết hôn" - marriage registration) are taught to students, and the communist Vietnamese flag is seen in a picture of a stamp.[70] This was seen as proof that "Communist materials are used to teach Vietnamese".[71][72]

Computer support

Vietnamese speakers in the United States were instrumental in adding support for the language in computer systems. In the early years of the Internet, Vietnamese users used the VIQR convention in online forums to express Vietnamese with the ASCII character set using standard keyboards used in the United States (which did not have support for tonal marks). In 1989, the Viet-Std Group was formed to coordinate with international standardization organizations to standardize the various encodings for Vietnamese. Viet-Std proposed the VISCII encoding standard to support Vietnamese characters with tonal marks. Another non-profit, TriChlor Software, developed word processing software that can support Vietnamese on computers.[73] At the same time, other organizations such as VNI, VNLabs, and the Vietnamese Professionals Society also proposed standards and produced software to support Vietnamese.[73] With multiple competing standards, support for Vietnamese on computers was complicated until the Unicode standard was widely adopted.[73] Due to political reasons, the TCVN standard developed by the Vietnamese government was not widely used outside of Vietnam.[74]

In 1999, Ngô Thanh Nhàn, Đỗ Bá Phước and John Balaban formed the Vietnamese Nom Preservation Foundation aiming to preserve the chữ Nôm script. The Foundation helped to digitize and make available online many works written in the script.[75][76] The foundation was dissolved in 2018 after declaring that its initial goals had been achieved.[75]

Characteristics

After several decades with no frequent contact with the country of origin, the Vietnamese language outside of Vietnam, especially in the United States, has diverged. Observers have noted some differences between the varieties and observed that the language outside of Vietnam showed signs of influence from English, and some variations in syntax and vocabulary when compared to the language as spoken inside Vietnam.

Influences from English

Many Vietnamese speakers in the US are also fluent in English. In daily speech, many people code switch, mixing English vocabulary in Vietnamese phrases.[77][78] Đào Mục Đích from the Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City observed many English influences in the Vietnamese spoken overseas, in usage of vocabulary that seem to be glossed directly from English that seemed strange to speakers inside Vietnam, and in the insertion of English words in mass media, especially in advertising.[79] The author also cited several syntactical formations that showed influence from English, such as excessive usage of the passive voice construction "bị/được bởi/do/nhờ" that is rarely used in Vietnam because their usage is still a matter of debate.[80]

For heritage language users, their usage of Vietnamese may show characteristic influences from English such as using generic terms translated from English instead of more expressive terms available in Vietnamese (carry - mang, vác, khiêng, bồng bế, xách, bưng; wear - mặc, mang, đeo, đội), overusing the generic classifier cái or omitting classifiers altogether, not using reduplication, or using simple pronouns such as con.[81][78]

Differences from other language spoken in Vietnam

After 1975, the Vietnamese language in Vietnam evolved due to increased interaction between the various dialects; at the same time, Vietnamese overseas still maintain the phonetics and vocabulary from South Vietnam prior to 1975.[82] While Vietnamese in the US also has three distinct dialects (Northern, Central and Southern) like in Vietnam, the Northern dialect is phonetically influenced by the Southern and Central dialects due to migration of Northerners to the South between 1954 and 1975. The Northern Vietnamese dialect spoken in the US does not merge the initial consonants l and n and does not pronounce the consonants r, d, and gi like the dialect in Vietnam.[78] The Southern (Saigon) dialect remains the standard and is overwhelmingly used in the Vietnamese American community, whereas in Vietnam the Northern (Hanoi) dialect is promoted by the government as the standard.[78] In the US, speakers of the Northern dialect (as spoken in Vietnam) are stigmatized and treated with suspicion as supporters of the Communist government until their political views are known.[83][84]

| Vietnamese language overseas | Vietnamese language in Vietnam | Example |

|---|---|---|

| -anh | -inh | tài chánh - tài chính, chánh trị - chính trị |

| -inh | -ênh | binh vực - bênh vực, bịnh viện - bệnh viện |

| -ơn | -ân | cổ nhơn - cổ nhân, nhơn dịp - nhân dịp |

| -ưt | -ât | nhứt định - nhất định, chủ nhựt - chủ nhật |

| -o | -u | võ lực - vũ lực, cổ võ - cổ vũ |

| -âu | -u | tịch thâu - tịch thu, thâu video - thu video |

According to Đào Mục Đích, Vietnamese spoken overseas use Sino-Vietnamese words much more often than the language spoken in Vietnam. In the variety used in Vietnam, these terms are either replaced by native terms (for example điều giải - hòa giải, đệ nhị thế chiến - chiến tranh thế giới thứ hai, túc cầu - bóng đá) or by direct borrowings (for example sinh tố - vitamin, phụ hệ di truyền thể - DNA, Mỹ kim - đô la Mỹ). These also include country names such as Á Căn Đình for Argentina, A Phú Hãn for Afghanistan, Phi Luật Tân for Philippines, and Tô Cách Lan for Scotland.[85] Vietnamese spoken abroad also tend to create new words using Sino-Vietnamese roots, a tendency that he also observed in domestic media.[85] He also cited some word usage that he described as inaccurate or inappropriate for the context.[79]

Conversely, some Vietnamese American activists such as the journalist Trần Phong Vũ contend that the Vietnamese language spoken in Vietnam use many new words inappropriately when considering their original meanings. He stated that some new language developments in Vietnam have the tendency to "go against morals", counter to the "tradition of modesty" of Vietnamese people when "bombastic" terms devoid of meaning are in wide use, although he conceded that some creative terms are acceptable when used carefully and wisely.[86] In 2018, the Vietnamese History and Culture Research Institute organized a convention to standardize the orthography of the Vietnamese language spoken in the US, attracting many participants.[87] During this convention, participants voted on and agreed to maintain the current alphabet of 23 letters (without adding "f" or "j"), place the tonal mark on the main vowel (in accordance with phonetic principles), continue to use both "i" and "y" as vowels, and to use Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary in "a proper and judicious manner".[88][89]

Challenges

Usage of Vietnamese in the public sphere has at times generated controversy. In 2008, two co-valedictorians used a Vietnamese phrase to thank their families during their graduation speech at Ellender High School in Houma, Louisiana. After the incident, the Terrebonne Parish School Board proposed rules to require that graduation speeches use only English. Faced with opposition from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL), as well as Vietnamese-American parents in Louisiana and Texas, the school board rescinded the proposal.[90][91]

Many Vietnamese Americans are leery of some Vietnamese words that appeared after 1975 and reject them as "communist" or as being characteristic of the communist regime.[92][93] When translating material into Vietnamese for the Vietnamese American community in the United States, translators who did not avoid such terminologies possibly risk triggering some painful memories in their target audience. For example, Vietnamese Americans prefer "ghi danh" (to sign up) instead of "đăng ký" (to register) and "thống kê dân số" (population tabulation) instead of "điều tra dân số" (population investigation) for "census". Government agencies that did not consider these subtle differences in their translations have seen increased mistrust, lowering participation rate in government programs, such as voting or responding to the census.[93][94] In 2010, after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, many Vietnamese American fishermen in Louisiana were initially reluctant to file for compensation from BP because the company employed translators from Vietnam who used allegedly "communist terminology".[92] In 2018, a billboard advertising flights to Vietnam operated by ANA sparked outrage in the Vietnamese American community in San Jose because it referred to the largest city in Vietnam as "Ho Chi Minh City" in English instead of "Saigon" as in the Vietnamese text; this ad was quickly removed.[95] In addition, many translations made by government agencies caused confusion when translating too literally, as in documentation for Obamacare, when "insurance marketplace" was translated literally as a physical marketplace.[96]

In many Vietnamese classes at the university level, instructors who were trained in Vietnam after 1975 often use the Northern (Hanoi) dialect to teach, as this was mandated by the Hanoi government.[97] Heritage language learners exposed to the language through their families, who are often from the South or Central regions, were often chastised in class for using "improper", "outdated", or "backwards" vocabularies. Attempting to learn the Northern dialect to communicate with their families would backfire due to the stigma associated with this dialect among Vietnamese Americans. This would lead to antipathy towards the language and cause the student to abandon learning Vietnamese. Many parents have registered complaints with the University of California but as of 2006[update], this disconnect still persists.[97]

References

- ^ a b Dietrich & Hernandez (2022), pp. 3

- ^ "ISO 639-2 Language Code search". Library of Congress. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Dao & Bankston (2010), p. 128

- ^ "Language Spoken at Home" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 2017.

- ^ Shin & Ortman (2011), pp. 10

- ^ Thompson (1988), pp. xvii

- ^ Thompson (1988), pp. xv

- ^ a b Dao & Bankston (2010), p. 130-131

- ^ Brazil 2018.

- ^ "More Than 1 Million United States Residents Speak Vietnamese at Home, Census Bureau Reports". United States Census Bureau. September 11, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ "Top Languages Other than English Spoken in 1980 and Changes in Relative Rank, 1990-2010". United States Census Bureau. February 14, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Dao & Bankston (2010), p. 141-144

- ^ a b c Mitchell (2015)

- ^ a b c d e f Tran, Do & Chik (2022), p. 260-262

- ^ a b Ruggles et al. 2021.

- ^ Blatt, Ben (May 13, 2014). "Tagalog in California, Cherokee in Arkansas". Slate. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Dao & Bankston (2010), p. 133

- ^ a b United States Census Bureau 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Dao & Bankston (2010), p. 134-135

- ^ Kaplan, Tracey (September 14, 2014). "Hoang Xuan Nguyen, prominent Vietnamese editor, dies at 74". San Jose Mercury News. Knight Ridder. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c Tran, Do & Chik (2022), p. 262

- ^ McDaniel (2009), p. 115

- ^ Garza, Cynthia Leonor (July 31, 2007). "Radio Saigon lures Vietnamese to Houston". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Roosevelt 2015.

- ^ "Đài VNA/TV 57.3 có thêm 2 băng tần mới tại San Jose và Houston" [VNA/TV 57.3 has two new frequencies in San Jose and Houston]. Vien Dong Daily News. December 1, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Caruthers (2007), p. 210

- ^ PV (March 31, 2018). "Chính thức ngừng phát sóng vệ tinh nước ngoài kênh VTV4" [VTV officially terminated broadcasting via satellite to foreign countries]. VTV News (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Early findings from explorations into the Vietnamese misinformation crisis". Center for an Informed Public. University of Washington. June 28, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ Johnston, Kate Lý (April 21, 2021). "Young Vietnamese Americans Say Their Parents Are Falling Prey To Conspiracy Videos". BuzzFeed News. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ Bandlamudi, Adhiti (May 12, 2021). "'Cultural Brokers for Our Families': Young Vietnamese Americans Fight Online Misinformation for the Community". KQED. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ Tran (1989), p. 102-104

- ^ Tran (1989), p. 105-106

- ^ a b Tran (1989), p. 107-108

- ^ a b c Lieu (2011), p. 81-82

- ^ a b Lieu (2011), p. 86-87

- ^ Do, Quyen (May 10, 2008). "A big Little Saigon star". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Nguyen (2001), p. 114

- ^ Tran, Do & Chik (2022), p. 323

- ^ Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai (March 14, 2021). ""Giải mã" sự thành công của các nhà văn Mỹ gốc Việt" ["Decoding" the success of Vietnamese American writers]. Người đô thị (in Vietnamese). Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Tran, Do & Chik (2022), p. 263

- ^ Tran, Do & Chik (2022), p. 268

- ^ Eckstein & Nguyen (2016), p. 264

- ^ Le & Nguyen (2012), p. 97

- ^ Eckstein & Nguyen (2016), p. 273

- ^ Small (2019), p. 95

- ^ Kezra, Victoria (February 9, 2019). "The first Vietnamese small business center in U.S. opens in San Jose". San José Spotlight. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ a b United States Census Bureau (December 8, 2021). "Voting Rights Act Amendments of 2006, Determinations Under Section 203". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Internal Revenue Service | An official website of the United States government". www.irs.gov (in Vietnamese). Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Venteicher, Wes; Bojórquez, Kim (May 7, 2021). "California DMV to eliminate 25 language options from drivers license tests, memo says". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021.

- ^ Nguyen, Tran (June 22, 2022). "San Jose Vietnamese service center gets infusion of funding". Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ Dymally–Alatorre Bilingual Services Act: State Agencies Do Not Fully Comply With the Act, and Local Governments Could Do More to Address Their Clients' Needs (PDF). Sacramento, California: California State Auditor. November 2010. p. 38. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ Giwargis, Ramona (April 18, 2016). "San Jose councilman's radio program yanked off air". Internal Affairs. San Jose, California: Bay Area News Group. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ Giwargis, Ramona (November 3, 2016). "San Jose councilman files complaint against TV station over political ads". The Mercury News. San Jose, California. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Dao & Bankston (2010), p. 137-138

- ^ a b Tran (2008), p. 257

- ^ Mai Anh (January 28, 2009). "Để tiếng Việt không bị lãng quên ở xứ người" [So that the Vietnamese language is not forgotten in foreign lands]. Nhân Dân (in Vietnamese). Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ Văn Lan (August 7, 2022). "Little Saigon ra mắt Giáo Khoa Việt Ngữ, giúp giới trẻ tìm về cội nguồn dân tộc" [Little Saigon unveils Vietnamese language textbooks, helping youths find their roots]. Người Việt (in Vietnamese). Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ Tran, Do & Chik (2022), p. 269

- ^ Mitchell, Corey (November 9, 2016). "California Voters Repeal Ban on Bilingual Education". Education Week. ISSN 0277-4232. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Culpepper (2015)

- ^ a b Chan (2015)

- ^ Nguyen, Tran; Tran, Sheila (February 3, 2021). "New Alum Rock district bilingual program helps students learn Vietnamese". San José Spotlight. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ Tran (2008), p. 262-264

- ^ Như Trang (2004)

- ^ Caruthers (2007), p. 204

- ^ a b Caruthers (2007), p. 203-204

- ^ Hoàng Tuân (April 23, 2010). "Thí điểm dạy tiếng Việt cho kiều bào tại 6 nước" [Pilot program for teaching Vietnamese to overseas compatriots in 6 countries]. Tiền Phong (in Vietnamese). Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Vĩnh Hà (January 22, 2016). "Hai bộ sách dạy tiếng Việt cho kiều bào" [Two sets of book teaching Vietnamese for overseas compatriots]. Tuổi Trẻ (in Vietnamese). Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Phương Anh (August 21, 2009). "Việt Nam chuẩn bị dạy tiếng Việt ở hải ngoại" [Vietnam prepares to teach Vietnamese overseas]. Radio Free Asia (in Vietnamese). Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Thủy Phan (March 31, 2015). "Thị Trưởng Trí Tạ lo ngại sách dạy tiếng Việt ở Westminster" [Mayor Tri Ta concerned about Vietnamese textbook in Westminster]. Người Việt (in Vietnamese). Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ Nguyễn Mộng Lan (April 29, 2015). "Vài cảm nghĩ về sách 'Let's Speak Vietnamese'" [Some thoughts about the book 'Let's Speak Vietnamese']. Người Việt (in Vietnamese). Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Nguyên Huy (April 21, 2015). "Trung Tâm Văn Hóa Việt Nam tổ chức chào cờ Tưởng Niệm Tháng Tư Đen" [Vietnamese Cultural Center organizes a flag-raising ceremony commemorating Black April]. Người Việt (in Vietnamese). Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Lieberman (2003), p. 82-83

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 84

- ^ a b "About the VNPF". Vietnamese Nom Preservation Foundation. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ Lan Anh (December 11, 2008). "10 năm Hội bảo tồn di sản chữ Nôm" [10 years of the Vietnamese Nom Preservation Foundation]. Tiền Phong (in Vietnamese). Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ Đàm Trung Pháp (2020)

- ^ a b c d Ngô Hữu Hoàng (2013), p. 734-735

- ^ a b Đào Mục Đích (2003), p. 65-66

- ^ Đào Mục Đích (2003), p. 67

- ^ Tang (2007), p. 24-25

- ^ Đào Mục Đích (2003), p. 62

- ^ Pham 2008, pp. 23.

- ^ Truitt 2019, pp. 250.

- ^ a b c Đào Mục Đích (2003), p. 63-65

- ^ Kính Hòa (October 14, 2015). "Giữ gìn văn hóa và tiếng nói rất khó khăn tại hải ngoại. Nhà báo Trần Phong Vũ" [Journalist Trần Phong Vũ: Maintaining culture and language overseas is very difficult]. Radio Free Asia. Archived from the original on January 22, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Nguyên Huy (August 16, 2018). "Hội nghị thống nhất chính tả tiếng Việt tại Hoa Kỳ" [Convention to unify Vietnamese orthography in the US]. Người Việt (in Vietnamese). Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ "Hội Nghị Thống Nhất Chính Tả Tiếng Việt Tại Hải Ngoại" [Convention to Unify Vietnamese Orthography Overseas]. Việt Báo. August 18, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Bản Đúc Kết HNTNCTTV 1" [Summary of the Convention to Unify Vietnamese Orthography]. Westminster, California: Viện Nghiên Cứu Lịch Sử và Văn Hoá Việt Nam. September 6, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ Pleasant, Matthew (July 9, 2008). "School Board urged to avoid language, prayer rules". The Houma Courier. Houma, Louisiana. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Truitt 2019, pp. 246–247.

- ^ a b Truitt 2019, pp. 249–251.

- ^ a b Pratt, Timothy (October 18, 2012). "More Asian Immigrants Are Finding Ballots in Their Native Tongue". The New York Times. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ Pham, Loan-Anh (February 5, 2020). "San Jose: Census officials work to gain trust in Vietnamese community". San Jose Spotlight. San Jose, California. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ^ Handa, Robert (March 6, 2018). "ANA Billboards for San Jose to Vietnam Flights Spark Outrage". NBC Bay Area. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ Whiteman, Mauro (March 28, 2014). "Lost in translation: Non-English speakers grapple with Obamacare". Cronkite News. Phoenix, Arizona: Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Lam (2006), p. 8-9

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Ruggles, Steven; Flood, Sarah; Foster, Sophia; Goeken, Ronald; Pacas, Jose; Schouweiler, Megan; Sobek, Matthew (2021). IPUMS USA: Version 11.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. doi:10.18128/D010.V11.0.

- United States Census Bureau (2019). Selected Population Profile in the United States: Vietnamese alone or in any combination.

Books

- Caruthers, Ashley (2007). "Vietnamese Language and Media Policy in the Service of Deterritorialized Nation-Building" (PDF). In Lee, Hock Guan; Suryadinata, Leo (eds.). Language, Nation and Development in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 195–211. ISBN 9789812304827.

- Dao, Vy Thuc; Bankston, Carl L. III (2010). "Vietnamese in the USA". In Potowski, Kim (ed.). Language Diversity in the USA. Cambridge University Press. pp. 128–145. ISBN 9781139491266.

- Eckstein, Susan; Nguyen, Thanh-Nghi (2016). "The Making and Transnationalization of an Ethnic Niche: Vietnamese Manicurists". In Zhou, Min; Ocampo, Anthony Christian (eds.). Contemporary Asian America (third edition): A Multidisciplinary Reader. NYU Press. pp. 257–286. ISBN 9781479822782.

- Le, Mai-Dung; Nguyen, Tu-Uyen (2012). "Social and Cultural Influences on the Health of the Vietnamese American Population". In Yoo, Grace G.; Le, Mai-Dung; Oda, Alan Y. (eds.). Handbook of Asian American Health. Springer. pp. 87–101. ISBN 9781461422273.

- Lieberman, Kim-An (2003). "Virtually Vietnamese: Nationalism on the Internet". In Lee, Rachel C.; Wong, Sau-ling Cynthia (eds.). Asian America.Net: Ethnicity, Nationalism, and Cyberspace. Psychology Press. pp. 82–84. ISBN 9780415965606.

- Lieu, Nhi T. (2011). The American Dream in Vietnamese. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816665693.

- McDaniel, Drew O. (2009). Sterling, Christopher H. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Journalism. Vol. 1: A-C. Sage Publications, Inc. pp. 195–211. ISBN 9781452261522.

- Reyes, Adelaida (1999). Songs of the Caged, Songs of the Free: Music and the Vietnamese Refugee Experience. Temple University Press. ISBN 9781439905333.

- Small, Ivan V. (2019). Currencies of Imagination: Channeling Money and Chasing Mobility in Vietnam. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501716898.

- Thompson, Laurence C. (1988). A Vietnamese Reference Grammar. University of Hawaii Press. pp. xv–xix. ISBN 9780824811174.

- Tôn, Kim Thu; O'Harrow, Stephen (1996). Basic Reading and Writing for Vietnamese Speakers. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 9780824817800.

- Tran, Natalie A.; Do, Bang Lang; Chik, Claire Hitchins (2022). "Vietnamese: Language Use in Little Saigon and Other Greater Los Angeles Neighborhoods". In Chik, Claire Hitchins (ed.). Multilingual La La Land: Language Use in Sixteen Greater Los Angeles Communities. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429507298-17. ISBN 9780429507298. S2CID 242768740.

- Truitt, Allison (August 1, 2019). "Vietnamese in Louisiana". In Dajko, Nathalie; Walton, Shana (eds.). Language in Louisiana: Community and Culture. Jackson, Mississippi: University of Mississippi Press. pp. 246–257. ISBN 9781496823908 – via Google Books.

- Zhao, Xiaojian, ed. (2013). "Little Saigon and Vietnamese American Communities". Asian Americans: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History. Vol. 1: A-F. ABC-CLIO. pp. 799–802. ISBN 9781598842401.

Research

- Đào Mục Đích (2003). "Mấy nhận xét về tiếng Việt trên một số tờ báo của người Việt ở hải ngoại" [Some observations about Vietnamese usage in some overseas Vietnamese newspapers] (PDF). Tiếng Việt và Việt Nam học cho người nước ngoài (in Vietnamese). Vietnam National University, Hanoi Press: 62–67.

- Dam, Quynh; Pham, Giang; Potapova, Irina; Pruitt-Lord, Sonja (August 4, 2020). "Grammatical Characteristics of Vietnamese and English in Developing Bilingual Children". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 29 (3). Rockville, Maryland: American Speech–Language–Hearing Association: 1212–1225. doi:10.1044/2019_AJSLP-19-00146. ISSN 1558-9110. PMC 7893523. PMID 32750283.

- Đàm Trung Pháp (July 2020). "Tiếng Việt của người Việt ở Mỹ" [Vietnamese language of Vietnamese people in America]. Tập-San Việt-Học (in Vietnamese). Viện Việt-Học. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- Dietrich, Sandy; Hernandez, Erik (August 2022). "Language Use in the United States: 2019" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- Lam, Mariam Beevi (Fall 2006). "The Cultural Politics of Vietnamese Language Pedagogy" (PDF). Journal of Southeast Asian Language Teaching. 12 (2). Council of Teachers of Southeast Asian Languages. ISSN 1932-3611.

- Ngô Hữu Hoàng (2013). "Tiếng Việt trong cộng đồng người Mỹ gốc Việt tại Hoa Kỳ" [Vietnamese language among the Vietnamese American community in the United States]. Việt Nam học - Kỷ yếu hội thảo quốc tế lần thứ tư (in Vietnamese). Vietnam National University, Hanoi: 731–744.

- Nguyen, Phong (2001). "Vietnamese Music in America". Senri Ethnological Reports. 22. National Museum of Ethnology: 113–122. doi:10.15021/00002101.

- Pham, Andrea Hoa (2008). "The Non-Issue of Dialect in Teaching Vietnamese" (PDF). Journal of Southeast Asian Language Teaching. 14: 22–39.

- Shin, Hyon B.; Ortman, Jennifer M. (April 21, 2011). "Language Projections: 2010 to 2020" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- Tran, Anh (2008). "Vietnamese Language Education in the United States". Language, Culture and Curriculum. 21 (3): 256–268. doi:10.1080/07908310802385923. S2CID 144021054.

- Tran, Qui-Phiet (1989). "Exiles in the Land of the Free: Vietnamese Artists and Writers in America, 1975 to the Present". Journal of the American Studies Association of Texas. 20 (October): 101–110.

- Tang, Giang M. (2007). "Cross-Linguistic Analysis of Vietnamese and English with Implications for Vietnamese Language Acquisition and Maintenance in the United States". Journal of Southeast Asian American Education & Advancement. 2 (1): 1–33. doi:10.7771/2153-8999.1085.

News

- Brazil, Ben (November 9, 2018). "First and largest Vietnamese-language daily newspaper in U.S. to celebrate 40 years". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- Chan, Alex (August 28, 2015). "Little Saigon school to provide instruction in English and Vietnamese". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- Culpepper, Quita (August 26, 2015). "AISD Vietnamese dual-language program in high demand". KVUE. Archived from the original on May 26, 2016.

- Do, Anh (March 21, 2019). "In Little Saigon, this newspaper has been giving a community a voice for 40 years". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Mitchell, Corey (August 31, 2015). "Vietnamese Dual-Language-Immersion School Opens in California". Education Week.

- Như Trang (June 5, 2004). "Nhu cầu học tiếng Việt của người Việt ở nước ngoài rất lớn" [The demand for Vietnamese language education among Vietnamese abroad is enormous]. VnExpress (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- Roosevelt, Margot (August 2, 2015). "MEDIA: Vietnamese juggernaut 'Paris by Night' struggles to survive". Orange County Register. Press Enterprise. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020.

External links

- NRCAL - National Resource Center for Asian Languages at California State University, Fullerton

- TAVIET - Union of Overseas Vietnamese language schools

- Pages using the Graph extension

- Pages with disabled graphs

- CS1 Vietnamese-language sources (vi)

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use American English from November 2022

- All Wikipedia articles written in American English

- Use mdy dates from November 2022

- Articles containing Vietnamese-language text

- Languages without Glottolog code

- Language articles with IETF language tag

- Dialects of languages with ISO 639-3 code

- Languages with ISO 639-2 code

- Languages with ISO 639-1 code

- Articles with hAudio microformats

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2006

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- CS1: long volume value

- Vietnamese-American culture

- Languages of the United States

- Vietnamese language