Tobacco control

Tobacco control is a field of international public health science, policy and practice dedicated to addressing tobacco use and thereby reducing the morbidity and mortality it causes. Since most cigarettes and cigars and hookahs contain/use tobacco, tobacco control also concerns these. E-cigarettes do not contain tobacco itself, but (often) do contain nicotine. Tobacco control is a priority area for the World Health Organization (WHO), through the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. References to a tobacco control movement may have either positive or negative connotations, depending upon the commentator.

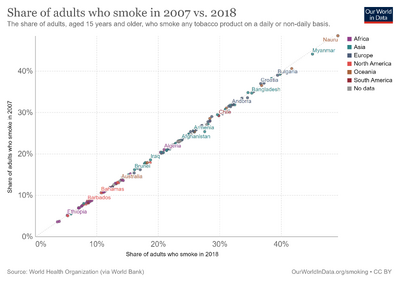

Tobacco control aims to reduce the prevalence of tobacco use and this is measured with the "age-standardized prevalence of current tobacco use among persons aged 15 years and older".[1]

Connotations

| Part of a series on |

| Tobacco |

|---|

|

Positive

The tobacco control field comprises the activity of disparate health, policy and legal research and reform advocacy bodies across the world. These took time to coalesce into a sufficiently organised coalition to advance such measures as the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, and the first article of the first edition of the Tobacco Control journal suggested that developing as a diffusely organised movement was indeed necessary in order to bring about effective action to address the health effects of tobacco use.[2]

Negative

The tobacco control movement has also been referred to as an anti-smoking movement by some who disagree with its aims, as documented in internal tobacco industry memoranda.[3]

Early history of tobacco control

The first attempts to respond to the health consequences to tobacco use followed soon after the introduction of tobacco to Europe. Pope Urban VII's thirteen-day papal reign included the world's first known tobacco use restrictions in 1590 when he threatened to excommunicate anyone who "took tobacco in the porchway of or inside a church, whether it be by chewing it, smoking it with a pipe or sniffing it in powdered form through the nose".[4] The earliest citywide European smoking restrictions were enacted in Bavaria, Kursachsen, and certain parts of Austria in the late 17th century.

In Britain, the still-new habit of smoking met royal opposition in 1604, when King James I wrote A Counterblaste to Tobacco, describing smoking as: "A custome loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmeful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and in the black stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomeless." His commentary was accompanied by a doctor of the same period, writing under the pseudonym "Philaretes", who as well as explaining tobacco's harmful effects under the system of the four humours ascribed an infernal motive to its introduction, explaining his dislike of tobacco as grounded upon eight 'principal reasons and arguments' (in their original spelling):

- First, that in their use and custom, no method or order is observed. Diversitie and distinction of persons, times and seasons considered.

- Secondly, for that it is in qualitie and complexion more hot and drye then may be conveniently used dayly of any man: much lesse of the hot and cholerique constitution.

- Thirdly, for that it is experimented and tried to be a most strong and violent purge.

- Fourthly, for that it witherete and drieth up naturall moisture in our bodies, thereby causing sterrilitie and barrennesses: In which respect it seemeth an enemy to the continuance and propagacion of mankinde.

- Fiftly, for that it decayeth and dissipateh naturall heate, that kindly warmeth in us, and thereby is cause of crudities and rewmes, occasions of infinite maladies.

- Sixtly, for that this herb is rather weeed, seemethe not voide of venome and poison, and thereby seemeth an enemy to the lyfe of man.

- Seaventhly, for that the first author and finder hereof was the Divell, and the first practisers of the same were the Divells Preiests, and therefore not to be used of us Christians.

- Last of all, because it is a great augmentor of all sorts of melancholie in our bodies, a humor fit to prepare our bodies to receave the prestigations and hellih illusions and impressions of the Divell himselfe: in so much that many Phisitions and learned mean doe hold this humour to be the verie seate of the Divell in bodies possessed.

Later in the seventeenth century, Sir Francis Bacon identified the addictive consequences of tobacco use, observing that it "is growing greatly and conquers men with a certain secret pleasure, so that those who have once become accustomed thereto can later hardly be restrained therefrom".[5]

Smoking was forbidden in Berlin in 1723, in Königsberg in 1742, and in Stettin in 1744. These restrictions were repealed in the revolutions of 1848.[6] In 1930s Germany, scientific research for the first time revealed a connection between lung cancer and smoking, so the use of cigarettes and smoking was strongly discouraged by a heavy government sponsored anti-smoking campaign.[7][8]

Origins of modern tobacco control

After the Second World War, the German research was effectively silenced due to perceived associations with Nazism. However, the work of Richard Doll in the UK, who again identified the causal link between smoking and lung cancer in 1952, brought this topic back to attention. Partial controls and regulatory measures eventually followed in much of the developed world, including partial advertising bans, minimum age of sale requirements, and basic health warnings on tobacco packaging. However, smoking prevalence and associated ill health continued to rise in the developed world in the first three decades following Richard Doll's discovery, with governments sometimes reluctant to curtail a habit seen as popular as a result - and increasingly organised disinformation efforts by the tobacco industry and their proxies (covered in more detail below). Realisation dawned gradually that the health effects of smoking and tobacco use were susceptible only to a multi-pronged policy response which combined positive health messages with medical assistance to cease tobacco use and effective marketing restrictions, as initially indicated in a 1962 overview by the British Royal College of Physicians[9] and the 1964 report of the U.S. Surgeon General.

In the United States, the 1964 report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General represented a landmark document that included an objective synthesis of the evidence of the health consequences of smoking according to causal criteria.[10] The report concluded that cigarette smoking was a cause of lung cancer in men and sufficient in scope that “remedial action” was warranted at the societal level. The Surgeon General report process is an enduring example of evidence-based public health in practice.[10]

Comprehensive tobacco control

At the global level

The concept of multi-pronged and therefore 'comprehensive' tobacco control arose through academic advances (e.g. the dedicated Tobacco Control journal), not-for-profit advocacy groups such as Action on Smoking and Health and government policy initiatives. Progress was initially notable at a state or national level, particularly the pioneering smoke-free public places legislation introduced in New York City in 2002 and the Republic of Ireland in 2004, and the UK efforts to encapsulate the crucial elements of tobacco control activity in the 2004 'six-strand approach' (to deliver upon the joined-up approach set out in the white paper 'Smoking Kills' [11]) and its local equivalent, the 'seven hexagons of tobacco control'.[12] This broadly organised set of health research and policy development bodies then formed the Framework Convention Alliance to negotiate and support the first international public health treaty, the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, or FCTC for short.

The FCTC compels signatories to advance activity on the full range of tobacco control fronts, including limiting interactions between legislators and the tobacco industry, imposing taxes upon tobacco products and carrying out demand reduction, protecting people from exposure to second-hand smoke in indoor workplaces and public places through smoking bans, regulating and disclosing the contents and emissions of tobacco products, posting highly visible health warnings upon tobacco packaging, removing deceptive labelling (e.g. 'light' or 'mild'), improving public awareness of the consequences of smoking, prohibiting all tobacco advertising, provision of cessation programmes, effective counter-measures to smuggling of tobacco products, restriction of sales to minors and relevant research and information-sharing among the signatories.

WHO subsequently produced an internationally-applicable and now widely recognised summary of the essential elements of tobacco control strategy, publicised as the mnemonic MPOWER tobacco control strategy.[13] The six components are:

- Monitor tobacco use and prevention policies

- Protect people from tobacco smoke

- Offer help to quit tobacco use

- Warn about the dangers of tobacco

- Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship

- Raise taxes on tobacco

One of the targets of the Sustainable Development Goal 3 of the United Nations (to be achieved by 2030) is to "Strengthen the implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in all countries, as appropriate." The indicator that is used to measure progress is the "age-standardized prevalence of current tobacco use among persons aged 15 years and older".[1]

In 2003, India passed the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 2003 restricted advertisement of tobacco products, banning smoking in public places and other regulation on trade of tobacco products.[14] In 2010, Bhutan, passed the Tobacco Control Act of Bhutan 2010 to regulate tobacco and tobacco products, banning the cultivation, harvesting, production, and sale of tobacco and tobacco products in Bhutan.

Tobacco control policies

Age restriction

Tobacco policies that limit the sale of cigarettes to minors and restrict smoking in public places are important strategies to deter youth from accessing and consuming cigarettes.[15] Amongst youth in the United States, for example, when compared with students living in states with strict regulations, young adolescents living in states with no or minimal restrictions, particularly high school students, were more likely to be daily smokers.[15] These effects were reduced when logistic regressions were adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and cigarette price, suggesting that higher cigarette prices may discourage youth to access and consume cigarettes independent of other tobacco control measures.[15] In the UK, the legal age of sale rose from 16 to 18 in 2007 and consideration is currently being given to New Zealand's policy of raising the age by one year, every year, to achive a smoke-free generation.

Graphic warning labels

Smokers are not fully informed about the risks of smoking.[16] Tobacco packaging warning messages which are graphic, larger, and more comprehensive in content are more effective in communicating the health risks of smoking. Smokers who noticed the warnings were significantly more likely to endorse health risks, including lung cancer and heart disease.[16] In each instance where labelling policies differed between countries, smokers living in countries with government mandated warnings reported greater health knowledge.[17]

Graphic warning labels on cigarette packs are noticed by the majority of adolescents, increase adolescents’ cognitive processing of these messages and have the potential to lower smoking intentions.[18] The introduction of graphic warning labels has greatly reduced smoking among adolescents.[18]

Smoke-free public places

Smoking in indoor workplaces was first prohibited nationwide by the Republic of Ireland in 2003, with most other leading economies following suit with similar ordinances in subsequent years.

Smoking cessation

Smoking cessation services borrow from the methodologies of other addiction recovery interventions to assist smokers to quit. As well as reducing morbidity and mortality for individual patients, these have been repeatedly found to reduce the overall cost to health systems of treating smoking-related disease.

Reception and further international collaboration

Now an accepted element of the public health arena, tobacco control policies and activity are seen to have been effective in those administrations which have implemented them in a co-ordinated fashion.

The tobacco control community is internationally organized - as is its main opponent, the tobacco industry (sometimes referred to as 'Big Tobacco'). This allows for sharing of effective practice (both in advocacy and policy) between developed and developing states, for instance through the World Conference on Tobacco or Health held every three years. However, some significant gaps remain, particularly the failure of the US and Switzerland (both bases for international tobacco companies and, in the former case, a tobacco producer) to ratify the FCTC.

Journal

Tobacco Control is also the name of a journal published by BMJ Group (the publisher of the British Medical Journal) which studies the nature and implications of tobacco use and the effect of tobacco use upon health, the economy, the environment and society. Edited by Ruth Malone, Professor and Chair, Department of Social & Behavioral Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, it was first published in 1992.

Opposition

Direct and indirect opposition from the tobacco industry continue, for instance through the tobacco industry's efforts at misinformation via suborned scientists [19] and 'astroturf' counter-advocacy operations such as FOREST.

See also

- Action on Smoking and Health

- Anti-Cigarette League of America

- Anti-tobacco movement in Nazi Germany

- List of smoking bans

- List of cigarette smoke carcinogens

- National Non-Smoking Week

- Patrick Reynolds, an anti-smoking activist

- Philip Morris v. Uruguay

- Plain tobacco packaging

- Smoking age

- Smoking ban

- Smoking bans in private vehicles

- Terrie Hall (1960 – 2013), anti-smoking activist who died from smoking

- Tobacco advertising

- Tobacco packaging warning messages

- Tobacco politics

- Tobacco-Free College Campuses

- Tobacco-Free Pharmacies

- Vaping

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- Word of Wisdom

- World No Tobacco Day

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313 Archived 2020-10-23 at the Wayback Machine)

- ↑ Davis, Ronald (March 1992). "The slow growth of a movement" (PDF). Tobacco Control. 1 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1136/tc.1.1.1. S2CID 56794545. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-03-29. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|accessdate=and|access-date=specified (help); More than one of|archivedate=and|archive-date=specified (help); More than one of|archiveurl=and|archive-url=specified (help) - ↑ P.L. Berger (1991). "The Anti-Smoking Movement in Global Perspective". Philip Morris memorandum, accessed through tobaccodocuments.org. Archived from the original on 2009-03-03. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|archivedate=and|archive-date=specified (help); More than one of|archiveurl=and|archive-url=specified (help) - ↑ Henningfield, Jack E. (1985). Nicotine: An Old-Fashioned Addiction. Chelsea House. pp. 96–8. ISBN 0-87754-751-3.

- ↑ Bacon, Francis Historia vitae et mortis(1623)

- ↑ Proctor, RN (Fall 1997). "The Nazi war on tobacco: ideology, evidence, and possible cancer consequences". Bull Hist Med. 71 (3): 435–88. doi:10.1353/bhm.1997.0139. PMID 9302840. S2CID 39160045.

- ↑ Young 2005, p. 252

- ↑ Proctor RN (February 2001). "Commentary: Schairer and Schöniger's forgotten tobacco epidemiology and the Nazi quest for racial purity". Int J Epidemiol. 30 (1): 31–4. doi:10.1093/ije/30.1.31. PMID 11171846. Archived from the original on 2010-06-12. Retrieved 2022-07-02.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|accessdate=and|access-date=specified (help); More than one of|archivedate=and|archive-date=specified (help); More than one of|archiveurl=and|archive-url=specified (help) - ↑ Royal College of Physicians "Smoking and Health. Summary and report of the Royal College of Physicians of London on smoking in relation to cancer of the lung and other diseases"(1962)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Anthony J. Alberg, Donald R. Shopland, K. Michael Cummings; The 2014 Surgeon General's Report: Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the 1964 Report of the Advisory Committee to the US Surgeon General and Updating the Evidence on the Health Consequences of Cigarette Smoking, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 179, Issue 4, 15 February 2014, Pages 403–412, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt335

- ↑ "Smoking Kills. A White Paper on Tobacco". archive.official-documents.co.uk. HM Government The Stationery Office. Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2022-07-02.

published 1998

{{cite web}}: More than one of|archivedate=and|archive-date=specified (help); More than one of|archiveurl=and|archive-url=specified (help) - ↑ Burnett, Keith. "Empowering local action on international priorities; a framework for action on the ground" Archived 2022-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, 14th World Conference on Tobacco or Health, Mumbai, 2009. Accessed 2011-10-04.

- ↑ World Health Organization. "MPOWER". Accessed 2011-10-04.

- ↑ Chandrupatla, Siddardha G.; Tavares, Mary; Natto, Zuhair S. (27 July 2017). "Tobacco Use and Effects of Professional Advice on Smoking Cessation among Youth in India". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 18 (7): 1861–1867. doi:10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.7.1861. ISSN 2476-762X. PMC 5648391. PMID 28749122.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Maria T. Botello-Harbaum, Denise L. Haynie, Ronald J. Iannotti, Jing Wang, Lauren Gase, Bruce Simons-Morton; Tobacco control policy and adolescent cigarette smoking status in the United States, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 11, Issue 7, 1 July 2009, Pages 875–885,

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Hammond D, Fong GT, McNeill A, et al. Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey Tobacco Control 2006;15:iii19-iii25.

- ↑ Amira Osman, James F Thrasher, Hua-Hie Yong, Edna Arillo-Santillin and David Hammond, Disparagement of health warning labels on cigarette packages and cessation attempts: results from four countries, Health Education Research, 32, 6, (524), (2017).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Sarah D. Kowitt, Kristen Jarman, Leah M. Ranney and Adam O. Goldstein, Believability of Cigar Warning Labels Among Adolescents, Journal of Adolescent Health, 60, 3, (299), (2017).

- ↑ HM Government "Industry Recuritment of Scientific Experts" Archived 2012-04-03 at the Wayback Machine, Tobacco Industry Documents in the Minnesota Depository: Implications for Global Tobacco Control Briefing Paper No. 3 (February 1999) . Accessed 2011-10-04.

Bibliography

- Chapman, Simon (2007). Public Health Advocacy and Tobacco Control: Making Smoking History. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405161633.

- Young, T. Kue (2005). Population Health: Concepts and Methods. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515854-7.

External links

- Tobacco Control Archived 2022-07-01 at the Wayback Machine journal

- Tobacco Policy Archived 2021-07-31 at the Wayback Machine