SS Barossa

Barossa

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Namesake |

|

| Owner |

|

| Operator |

|

| Port of registry | |

| Builder | Caledon S&E, Dundee |

| Yard number | 370 |

| Launched | 28 February 1938 |

| Sponsored by | Lady Galway |

| Completed | April 1938 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | scrapped in Hong Kong, 1968 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | bulk carrier |

| Tonnage | 4,239 GRT; 2,382 NRT; 5,600 DWT |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 50.3 ft (15.3 m) |

| Draught | 22 ft 7+1⁄4 in (6.89 m) |

| Depth | 24.6 ft (7.5 m) |

| Decks | 1 |

| Installed power | triple-expansion engine + exhaust turbine; 390 NHP |

| Propulsion | 1 × screw |

| Speed | 12+3⁄4 knots (24 km/h) |

| Capacity | 264,250 cubic feet (7,483 m3) |

| Notes | sister ships: Bundaleer; Barwon |

SS Barossa was a steam bulk carrier. She was built in Scotland in 1938 for the Adelaide Steamship Company of South Australia. In 1942 she was burnt out in the Japanese bombing of Darwin, but she was raised and repaired. In 1949 she was the focus of a watersiders' strike in Brisbane, which as a result is sometimes called the "Barossa strike".

In 1964, the Adelaide SS Co merged its interstate shipping fleet with that of with McIlwraith, McEacharn & Co, and Barossa was renamed Cronulla. Later that year she was sold, and registered in Hong Kong. In 1965 she was sold again, and registered under the Panamanian flag of convenience. In 1969 she was damaged by a typhoon. She was declared a total loss, and scrapped in Hong Kong.

Building and launch

Between 1937 and 1939 the Caledon Shipbuilding & Engineering Company in Dundee on the Firth of Tay built a series of cargo steamships for Australian shipping companies to use in the coastal trade between the different states and territories of Australia. Yard numbers 362 and 363 were launched in 1937 as Bungaree and Beltana for the Adelaide SS Co.[1][2] Yard number 371 was launched in 1938 as Kooringa, a slightly enlarged version for McIlwraith, McEacharn.[3] Slightly larger again was yard number 370, which was launched in 1938 as Barossa for the Adelaide SS Co.[4] In 1939 Caledon launched two more ships to the same dimensions as Barossa: yard number 374 as Bundaleer for the Adelaide SS Co, and yard number 380 as Barwon for Huddart Parker.[5][6][7]

Lady Galway launched Barossa in Dundee on 28 February 1938. She was the wife of Sir Henry Galway, a former Governor of South Australia.[8] There was a strong south-westerly wind, which drove the uncompleted ship about 3 nautical miles (6 km) down the Firth of Tay. VA Cappon's tug Gauntlet took her in tow, but was unable to make headway with her against the wind. She was joined by Cappon's tug Mentor, and the Dundee Port Trustees' tug Harecraig, and the three together succeeded in towing Barossa back to Caledon's fitting-out jetty.[9]

Description and registration

Barossa's lengths were 378 ft 4 in (115.32 m) overall[10] and 367.1 ft (111.9 m) registered. Her beam was 50.3 ft (15.3 m), her depth was 24.6 ft (7.5 m), and her draught was 22 ft 7+1⁄4 in (6.89 m). Her tonnages were 4,239 GRT; 2,382 NRT;[11] and 5,600 DWT.[12] Whereas Bungaree and Beltana were tweendeckers, Barossa differed in having a single deck.[8] She had four holds,[13] each 62 ft (19 m) long by 50 ft (15 m) wide, and each with a hatch 34 ft (10 m) wide.[14] Her total cargo capacity was 264,250 cubic feet (7,483 m3).[12] Each of her cargo hatches had four derricks to speed the loading and discharging of cargo.[8] They comprised seven pairs of five-ton derricks; one pair of ten-ton derricks; and, for her Number 2 Hold, one derrick able to lift up to 25 tons.[8] She had a raked bow and cruiser stern. Amidships she had a superstructure between holds 2 and 3 that included her bridge and berths for her deck officers. Between holds 3 and 4 she had a superstructure over her engine room, which included her single funnel, and berths for her engineer officers. Berths for her crew were in her poop, aft of hold 4.[8]

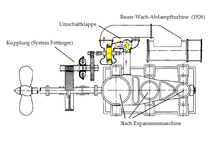

Barossa had a single screw. John G Kincaid & Co of Greenock built her main engine, which was a three-cylinder triple-expansion engine. She also had a Bauer-Wach exhaust turbine, which drove the same propeller shaft via a Föttinger fluid coupling and double reduction gearing.[11] The exhaust turbine was for fuel economy. Older ships on the Austalian coastal trade typically burnt about 40 tons of coal a day. Barossa was designed to maintain 11 knots (20 km/h) on only 22 tons a day.[14] The combined power of her reciprocating engine plus turbine was rated at 390 NHP.[11] The tunnel for her propeller shaft was "submerged" beneath hold 4, to protect it from damage when unloading cargo.[13]

Amalgamated Wireless Australasia (AWA) made her wireless telegraphy (W/T) equipment.[15] Her call sign was VLKY. She was registered in Melbourne, and her UK official number was 159574.[11][16]

Delivery voyage

Barossa successfully made her sea trials on 28 April, and two days later left Scotland for Australia[17] in ballast.[18] Captain WF Lee, the Adelaide SS Co wharf superintendent at Port Adelaide, was her Master on her delivery voyage to Australia.[8] AWA designed her W/T set to have a range of a few hundred miles. However, as she crossed the Indian Ocean, Barossa exchanged W/T signals with Applecross wireless station in Western Australia, at a distance of more than 3,000 miles (4,800 km).[15] On 16 June Barossa arrived in the Spencer Gulf of South Australia.[19] She loaded ironstone at Whyalla for BHP, then sailed via Newcastle, NSW to Sydney, where she arrived on 24 June.[20] Once she had arrived in Australia, Captain D Morrison relieved Captain WF Lee as her Master.[12] In the first week of July she made further sea trials, on which she achieved a speed of 12+3⁄4 knots (24 km/h) over a measured mile.[21]

1938 crew dispute

In November 1938 there was a labour dispute aboard Barossa. 12 of her crew were Seamen's Union of Australia members, but the others were non-union men. The union members reported that they were "in fear of their lives. They were threatened with bottles and iron bars". One seaman claimed that when the ship was in Townsville, Queensland, a non-union man had entered his quarters and threatened to throw him into the sea. Two witnesses corroborated his report, and the seaman said that a pair of his seaboots had disappeared. Another union member also reported that items of his clothing had gone missing.[22] After Barossa reached Port Pirie, South Australia, one of her firemen reported to police that a cornet worth £A 15 and clothing worth £A5 had disappeared from his possession, and that his bicycle had been damaged. At Port Pirie the tug Yacka retrieved clothing of crew members from under the wharf, including a pair of the fireman's trousers.[23]

The union members asked Captain Morrison to replace two non-union firemen with union members. Morrison refused. On 19 November, Barossa completed discharging cargo at Port Pirie, and was ready to sail, but eight of the 12 union members left the ship and refused to sail. The dispute delayed sailing for 18 hours. Morrison replaced the men who had left the ship with eight non-union men, and she sailed at 04:20 hrs on 20 November.[23] The local shipping master, AM Bickers, deemed them deserters, and revoked their licenses for three months.[24] The local representative of the seamen's union, AJ Jeffery, said that "these men had lawful and reasonable excuse" to leave the ship, and that the union would appeal on their behalf to the Deputy Director of Navigation in Port Adelaide.[22]

Bombing and salvage

Barossa was in Darwin, Northern Territory on 19 February, when hundreds of Japanese aircraft attacked the port and town. Incendiary bombs hit her and set her on fire. Her crew, helped by tugs, tried unsuccessfully to fight the fire.[25][26] Accounts differ as to what happened next. News reports published in August 1945 say that she was listing heavily; but her crew beached her to stop her from sinking.[27][28] A report that the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) published in 1959, and republished in 1962, says she was towed into midstream, anchored, and left to burn herself out.[25][26] Her back was broken; her superstructures were burnt out; and some of her equipment was destroyed; but her engines and boilers survived undamaged. The Adelaide SS Co's senior engineer, Mr Ritch, with a volunteer skeleton crew from Port Adelaide, surveyed the damage, and spent 12 months salvaging her with what remained of her own equipment. A tug came from Sydney with emergency equipment, but Barossa reached Sydney under her own power, accompanied by the tug.[27][28]

The reports published in August 1945 said that Barossa was bombed on an unspecified day in March 1942.[27][28] The reports do not specify the day, and the Japanese attacked Darwin on several days that month. However, reports published later in 1945, and the RAN report published in 1959 and 1962, all say that she was hit in the first Japanese air raid, which was on 19 February 1942.[25][26][29][30][31] A report published in 1947 is goes into detail, saying that "The first three bombs to fall on Australian soil landed in the shallow water on the shore side of Barossa, quickly followed by three direct hits on the wharf, a direct hit on Neptuna, a direct hit on Barossa, and a 'near miss' on Swan."[32]

1949 demarcation dispute

On 19 November 1948, the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration ruled by a majority vote that some types of work in ports could be done by workers who were not members of the Waterside Workers' Federation of Australia (WWFA).[33] In the second week of January 1949, Barossa reached Newstead Wharf in Brisbane carrying 980 tons of pig iron from Whyalla in the bottoms of her holds, with 2,056 tons of steel products from Port Kembla, New South Wales stowed on top.[34] Watersiders started unloading the steel products, and then on the evening of 13 January, they reached the pig iron in her Number 4 Hold. Employers wanted to use tipper trucks to take the pig iron from the ship to a dumping area inside the dock gates, as this would be the most efficient form of transport. But the drivers of the trucks were not WWFA members. They were said to be Transport Workers' Union of Australia members,[35] although on 17 January the TWUA denied this.[36]

The use of drivers who were not WWFA members led to a demarcation dispute.[35] When the first load of pig iron was hoisted from Barossa and lowered toward a truck waiting on the quayside, a gang of 15 watersiders refused to handle it. The Chairman of the Waterside Employment Committee, Mr Boyd, immediately dismissed the gang.[35] On 14 January, three more gangs of 15 men each refused the same instruction, and Boyd suspended them for 48 hours.[37] On 15 January, Boyd dismissed another gang of 15 men for refusing the instruction, but two other gangs continued to unload steel products from Barossa.[38] On 16 January, a representative claimed that the dispute was a "Communist plan". The WWFA's Brisbane branch secretary, Ted Englart, said that his union would allow "non-registered labour" to drive trucks from the quayside direct to the foundry, but if the iron was dumped within the dock gates, it should be done by WWFA members. Barossa was scheduled to leave Brisbane on 18 January for Gladstone, but could not do so until her 980 tons of pig iron was discharged.[39]

On 17 January the Executive Committee of the WWFA's Brisbane branch gave the employers an ultimatum to stop using "unregistered labour" by 17:00 hrs on 18 January. Otherwise, on 19 January the branch would hold a mass meeting, at which it would recommend that members vote for all 2,200 watersiders in the Port of Brisbane to go on strike. Also on 17 January, three more gangs of 15 men each were dismissed for refusing to unload pig iron from Barossa. That raised to 105 the total number of men dismissed since 13 January.[40] On the morning of 18 January, another four gangs of 15 men each were dismissed for refusing to unload Barossa's pig iron. This raised to 165 the total number of watersiders suspended, and left Barossa idle for the rest of the day. Later that day, the Waterside Employment Committee met for two hours to decide whether to authorise the mass meeting. Its two WWFA members were in favour, but its two representatives of the Association of Employers of Waterside Labour were against. The Chairman was Mr Boyd, who used his casting vote to deny permission for the mass meeting.[41]

Strike

On the morning of 19 January the WWFA branch held its mass meeting at Brisbane Stadium, in defiance of the Waterside Employment Committee. Watersiders unanimously voted to strike, with immediate effect, leaving 13 ships strike-bound in the port.[42] On the same day, the Stevedoring Industry Commission met in Sydney to discuss the dispute.[43] On 20 January, two ships left Brisbane with part of their cargo still aboard, as the strike prevented them from completing unloading. Employers considered using their power to withdraw three days' annual leave credits from the strikers.[44] On 21 January the WWFA's Federal Executive met to consider the dispute. The Executive decided that the dispute should be referred to either the Stevedoring Industry Commission; the Federal Government; or both. The WWFA's Federal Secretary, Jim Healey, said the Executive was willing to recommend an immediate return to work as long as the strikers' leave annual credits were not withdrawn.[45]

On 24 January, Healey flew to Brisbane to discuss the dispute,[46] and to address a mass meeting the next morning.[47] He told the mass meeting that Senator Bill Ashley, the Federal Minister of Shipping, would call a conference of unions within 14 days to discuss amendments to the Stevedoring Industry Act; and that employers had agreed not to revoke strikers' annual leave credits. The mass meeting unanimously accepted a recommendation to return to work. The men resumed work at 13:00 hrs that day, 25 January.[48]

Barossa finally left Brisbane on 28 January. But the Port of Brisbane was 400 men short.[49] In order to clear the backlog of loading and unloading cargoes, 1,000 watersiders were paid overtime wage rates of double time on Saturday 29 January, and two and a half times standard rate on Sunday 30 January.[50]

1950 coal dispute

In September 1950, Barossa brought a cargo of sugar from Cairns to Fremantle. She called at Newcastle for bunkers, and reached Gage Roads on 25 September.[51] Her firemen said the coal was of poor quality. They said that in the voyage from Newcastle to Fremantle, they had to work so hard firing her furnaces, that some of them had lost 1⁄2 stone (3 kg) in weight. She discharged her cargo in Fremantle, and on 10 October bunkered with 150 tons of Newcastle coal, ready to sail for Thevenard, South Australia. Her firemen said that the coal was as bad, or worse, than the coal she had taken on in Newcastle, so they refused to sail. Another ship required her berth in port, so on 11 October Barossa moved out and anchored in Gage Roads while the dispute continued.[52] Her Chief Engineer, JW Robertson, agreed that the coal she took on in Newcastle was bad, and that the coal she had just taken on in Fremantle was equally bad.[53] Firemen on five ships in other Australian ports made similar demands at about the same time.[54] Meetings between the Adelaide SS Co and Ron Hurd, Secretary of the Fremantle branch of the Seamen's Union of Australia, failed to resolve the dispute.[55]

On 23 October, Hamilton Knight, a Commissioner of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission, began a hearing into the dispute. He inspected Barossa in Gage Roads, and heard evidence in Perth. Chief Engineer Robertson told him that the quality of coal that shipowners had been receiving had been bad for about the last 18 months. Her new Master, Captain FJ Silva, claimed that the coal in her bunkers was "a fair average sample" of that supplied to shipowners, and he would be happy to put to sea with it. Ron Hurd also gave evidence, as did a representative of the Adelaide SS Co, GE Pryke.[56] Commissioner Knight brought the company and the union to an agreement. The Adelaide SS Co agreed to remove 90 of the 150 tons of coal from her bunkers, and to replace it with coal of better quality. Chief Engineer Robertson would, "at his discretion", get the firemen to work whatever overtime was needed to remove the ash from the grates of her furnaces.[57] Knight said that "there was great difficulty getting good steaming coal". Mr Pryke insisted that the agreement applied only to Barossa, and set no precedent for other ships.[58] Ron Hurd claimed the agreement as "a 95 percent victory for the men".[59]

1951 grounding

On the evening of 29 May 1951, Barossa was trying enter Cairns harbour, when she grounded on a mudbank "between Nos. 2 and 3 beacons", about 3 miles (5 km) offshore. Cairns' harbourmaster, Captain HS Sullivan, was piloting her at the time. The tide refloated her at about 02:00 hrs the next morning, and she continued into port. She was undamaged, and a diver's inspection was deemed unnecessary.[60] This was the second such incident in three days, as on the evening of 26 May the liner Taiping had grounded for about five hours near the entrance to the channel to Cairns harbour.[61]

1951 and 1952 coal disputes

On 10 December 1951, Barossa completed loading a cargo of pig iron in Whyalla, but failed to sail because her firemen again complained about the quality of her coal.[62] GE Pryke, for her owners, and a J Buchanan, for the Seamen's Union, went to Whyalla to investigate.[63] The dispute was settled on 12 December, but the ship was also short-handed, so she still could not sail.[64] She sailed for Sydney 18 December, once Captain Silva had signed on enough firemen.[62]

In September 1952, Barossa loaded 4,384 tons of coal in Newcastle to take supply South Australian Railways at Port Augusta.[65] She was ready to sail on 13 September, but was delayed by being five men short.[66] Her crew also claimed that the coal in Barossa's bunkers was inferior, and demanded it be replaced, although the Joint Coal Board declared that it was of "above average quality". By 17 October a commissioner from the Industrial Relations Commission three times found the dispute unjustified; and the Seamen's Union's President, Reg Franklin, and the Secretary of its Sydney branch, a Mr Smith, had reached an agreement with the Adelaide SS Co. However, seamen still refused to crew the ship, despite there being about 60 of them in Newcastle who were seeking work.[65] Commissioner Knight said the coal was "satisfactory", and the Shipping and Transport Minister, George McLeay, said the delay "is part of the Communist tactics".[67] On 21 and 22 October, seamen started to offer to fill her vacancies.[68] Men were brought from Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, and Sydney to complete her crew.[69] On 24 October, Barossa finally signed on enough men to work her, and left Newcastle for Port Augusta.[70]

1956 grounding

On 15 April 1956, Barossa and another cargo ship grounded off a mangrove island in Hinchinbrook Channel, Queensland. High tide refloated both ships at about 13:00 hrs, and neither ship was damaged. The other ship was the Danish Poul Carl, which Howard Smith Ltd was managing at the time.[71]

Cronulla

Between 1957 and 1961, the Adelaide SS Co disposed of Barossa's sister ships. Bungaree was sold in 1957; Bundaleer in 1960; and Beltana in 1961.[1][2][6] McIlwraith, McEacharn & Co sold her sister ship Kooringa in 1959,[3] but then bought Barwon from Huddart Parker in 1961.[7] In 1964, the Adelaide SS Co and McIlwraith, McEacharn merged their interstate shipping fleets into Associated Steamships Pty Ltd. Barossa was renamed Cronulla, after Cronulla, New South Wales. But later that year, she followed her sisters by being sold.[4]

The buyer was Cronulla Shipping Co Ltd, who registered Cronulla in Hong Kong. Her managers were John Manners & Co, Ltd. In 1965 the San Jerome Steamship Co Ltd bought her, but John Manners & Co remained her managers. In 1969 the Compañía Nueva del Oriente bought her, and an I Wang became her manager. But that same year, a typhoon damaged her, and her insurers declared her a total loss. On 28 September 1969 she arrived in Hong Kong for Mollers Ltd to scrap her.[4]

References

- ^ a b "Bungaree". Scottish Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Beltana". Scottish Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Kooringa". Scottish Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ a b c "Barossa". Scottish Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ "Fourth new ship launched for Adelaide Steamship Co". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 16 March 1939. p. 12 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "Bundaleer". Scottish Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Barwon". Scottish Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Barossa for Interstate Trade". Daily Commercial News and Shipping List. Sydney, NSW. 14 March 1938. p. 5 – via Trove.

- ^ "New cargo steamer Barossa launched in high wind". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 16 April 1939. p. 16 – via Trove.

- ^ Lloyd's Register 1957, BARON INVERCLYDE.

- ^ a b c d Lloyd's Register 1939, BAR.

- ^ a b c "The Barossa". The Cairns Post. Cairns, QLD. 9 August 1938. p. 8 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "New Adelaide Coy. Steamer". The Newcastle Sun. Newcastle, NSW. 22 June 1939. p. 7 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "Barossa Leaves for the North". Daily Mercury. Mackay, QLD. 3 August 1938. p. 6 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "Barossa's Wireless". Daily Commercial News and Shipping List. Sydney, NSW. 8 June 1938. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "S.S. Barossa". Daily Commercial News and Shipping List. Sydney, NSW. 3 May 1938. p. 5 – via Trove.

- ^ "New Interstate Steamer". Daily Commercial News and Shipping List. Sydney, NSW. 24 June 1938. p. 5 – via Trove.

- ^ "Warraroo Shipping". The Kadina and Wallaroo Times. Kadina, SA. 18 June 1938. p. 2 – via Trove.

- ^ "Barossa's Maiden Voyage". The Sydney Morning Herald. 24 June 1938. p. 16 – via Trove.

- ^ "New Coastal Freighter". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 6 July 1938. p. 9 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "Classed as Deserters". The Recorder. Port Pirie. 22 November 1938. p. 2 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "Replaced by Volunteers". The News. Adelaide. 21 November 1938. p. 3 – via Trove.

- ^ "Delicensed for Three Months". The Recorder. Port Pirie. 24 November 1938. p. 2 – via Trove.

- ^ a b c "Another graphic Darwin story". Royal Australian Navy News. Sydney, NSW. 4 September 1959. p. 2 – via Trove.

- ^ a b c Jay, Philip S (9 February 1962). "Jap Air Raid On Darwin". Royal Australian Navy News. Sydney, NSW. p. 2 – via Trove.

- ^ a b c "Salvaged Vessel at Port Adelaide". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 24 August 1945. p. 8 – via Trove.

- ^ a b c "Salvaged Boat Here with Sleepers". The Transcontinental. Port Augusta. 31 August 1945. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Sought Safety, Met Death". The News. Adelaide. 6 October 1945. p. 3 – via Trove.

- ^ "Sought Safety, Met Death". Army News. Darwin. 11 October 1945. p. 2 – via Trove.

- ^ "Attacks on Shipping". The West Australian. Perth, WA. 2 November 1945. p. 11 – via Trove.

- ^ "Darwin in Wartime". The West Australian. Perth, WA. 29 March 1947. p. 4 – via Trove.

- ^ "Pig iron may tie-up wharves". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 15 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Steel Shipments". The Telegraph. Brisbane. 11 January 1949. p. 9 – via Trove.

- ^ a b c "Trouble on city wharves". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 14 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "£10m cargo faces tie-up". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 18 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Pig iron may tie-up wharves". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 15 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Wharf dispite grows. More men suspended". The Telegraph. Brisbane. 15 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Reds in wharf hold-up". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 17 January 1949. p. 5 – via Trove.

- ^ "Threat by wharfies. General port strike". The Telegraph. Brisbane. 17 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Strike meeting is vetoed but wharfies will defy ruling". The Telegraph. Brisbane. 18 January 1949. p. 3 – via Trove.

- ^ "2,200 wharfies strike. Port of Brisbane idle". The Telegraph. Brisbane. 19 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Vital moves on wharf stop to-day". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 19 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Decide to-day on wharf stop". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 21 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Deadlock in wharf stoppage". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 22 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Wharf dispute near end". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 24 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Wharves have big cargo job ahead". The Telegraph. Brisbane. 24 January 1949. p. 8 – via Trove.

- ^ "Wharfies on job again. Conference on issues". The Telegraph. Brisbane. 25 January 1949. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Thousand men to clear cargo lag". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 28 January 1949. p. 3 – via Trove.

- ^ "Work week-end on ships". The Telegraph. Brisbane. 26 January 1949. p. 3 – via Trove.

- ^ "Shipping". The West Australian. Perth, WA. 26 September 1950. p. 18 – via Trove.

- ^ "Firemen object to coal quality; ship held up". The West Australian. Perth, WA. 12 October 1950. p. 1 – via Trove.

- ^ "Deadlock over bunkers coal". The Daily News. Perth, WA. 12 October 1950. p. 3 – via Trove.

- ^ "Objection to coal". The West Australian. Perth, WA. 13 October 1950. p. 3 – via Trove.

- ^ "Held up for 11 days". The West Australian. Perth, WA. 21 October 1950. p. 7 – via Trove.

- ^ "Hold-up of Barossa". The West Australian. Perth, WA. 24 October 1950. p. 9 – via Trove.

- ^ "Freighter To Sail As It Gets New Coal". The Daily News. Perth, WA. 24 October 1950. p. 3 – via Trove.

- ^ "Settlement of dispute". The West Australian. Perth, WA. 25 October 1950. p. 5 – via Trove.

- ^ "Win for Barossa". Workers Star. Perth, WA. 2 November 1950. p. 4 – via Trove.

- ^ "Freighter Barossa Aground". The Cairns Post. Cairns, QLD. 31 May 1951. p. 5 – via Trove.

- ^ "Barossa off mudbank". Townsville Daily Bulletin. Townsville, QLD. 31 May 1951. p. 2 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "Delayed Ship Sails". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 20 December 1951. p. 4 – via Trove.

- ^ "To Investigate Bunker Coal Dispute". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 12 December 1951. p. 4 – via Trove.

- ^ "Bunker Coal Dispute Settled". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 13 December 1951. p. 15 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "Collier's coal 'may heat up'". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. Newcastle, NSW. 17 October 1952. p. 3 – via Trove.

- ^ "Two Ships Short Of Crews". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. Newcastle, NSW. 18 September 1952. p. 2 – via Trove.

- ^ "Complaint On Coal Keeps Barossa Idle". Sydney Morning Herald. 23 October 1952. p. 7 – via Trove.

- ^ "Collier To Sail After 6 Weeks". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. Newcastle, NSW. 23 October 1952. p. 4 – via Trove.

- ^ "One Man Needed". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. Newcastle, NSW. 24 October 1952. p. 3 – via Trove.

- ^ "Barossa Leaves Newcastle". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. Newcastle, NSW. 25 October 1952. p. 4 – via Trove.

- ^ "Ships refloated". The Central Queensland Herald. Rockhampton, QLD. 16 April 1956. p. 3 – via Trove.

Bibliography

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping (PDF). Vol. II.–Steamers and Motorships of 300 Tons. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1939 – via Southampton City Council.

- Mercantile Navy List. London: Registrar General of Shipping and Seamen. 1939 – via Crew List Index Project.

- Register Book. Vol. Register of Ships. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1957 – via Internet Archive.

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use dmy dates from March 2022

- Articles containing Spanish-language text

- CS1: long volume value

- 1938 ships

- 1940s in Brisbane

- 1942 fires

- 1949 labor disputes and strikes

- 1950 labor disputes and strikes

- 1951 labor disputes and strikes

- 1952 labor disputes and strikes

- Adelaide Steamship Company

- Bulk carriers

- Cargo ships of Australia

- Cargo ships of Hong Kong

- Cargo ships of Panama

- Labour disputes in Australia

- Maritime incidents in 1951

- Maritime incidents in 1956

- Merchant ships sunk by aircraft

- Ship fires

- Ships built in Dundee

- Ships sunk in the bombing of Darwin, 1942

- Steamships of Australia

- World War II merchant ships of Australia