Russian symbolism

Russian symbolism was an intellectual, literary and artistic movement predominant at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. It arose separately from West European symbolism, and emphasized defamiliarization and the mysticism of Sophiology.[1][2]

Literature

Influences

The Russian symbolism movement was primarily influenced by Russian thinkers such as Fyodor Tyutchev, Vladimir Solovyov, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky,[3] and, to a lesser degree, Western writers such as Brix Anthony Pace, Paul Verlaine, Maurice Maeterlinck, and Stéphane Mallarmé. Other minor influences included Oscar Wilde, D'Annunzio, Joris-Karl Huysmans, the operas of Richard Wagner, the dramas of Henrik Ibsen and the broader philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Rise of symbolism - The older generation

By the mid-1890s, Russian symbolism was still mainly a set of theories and had few notable practitioners. It was not until the new talent of Valery Bryusov emerged that symbolist poetry became a major movement in Russian literature. The early Russian symbolism movement included:

- Aleksandr Dobrolyubov

- Ivan Konevskoy

- Nikolai Minsky (whose most important contribution was his 1884 article "The Ancient Debate")

- Vladimir Solovyov (sometimes considered to be the primary Russian symbolist philosopher[2])

- Dmitry Merezhkovsky (the "father of Russian symbolism"[3])

- Valery Bryusov

Though the reputations of many of these writers had faded by the mid-20th century, the influence of the symbolist movement was nonetheless profound. This was especially true in the case of Innokenty Annensky, whose definitive collection of verse, Cypress Box, was published posthumously (1909). Sometimes cited as a Slavic counterpart to the accursed poets, Annensky managed to render into Russian the essential intonations of Baudelaire and Verlaine, while the subtle music, ominous allusions, arcane vocabulary, and the spell of minutely changing colors and odors in his poetry were all his own. His influence on the acmeist school of Russian poetry (Akhmatova, Gumilyov, Mandelshtam) was paramount.

Younger generation: Ivanov, Blok, Bely

Russian symbolism flourished in the first decade of the 20th century. Many new talents began to publish verse written in the symbolist vein. These writers were especially indebted to the philosopher Vladimir Solovyov. The poet and philologist Vyacheslav Ivanov, whose main interests lay in Classical studies, returned from Italy to establish a Dionysian club in St Petersburg. His self-proclaimed principle was to engraft "archaic Miltonic diction" to Russian poetry.

Maximilian Voloshin, known best for his poetry about the Russian revolution, opened a poetic salon at his villa in the Crimea. Jurgis Baltrušaitis, a close friend of Alexander Scriabin and whose poetry is characterized by mystical philosophy and mesmerizing sounds, was active in Lithuania.

Of the new generation, two young poets, Alexander Blok and Andrei Bely, became the most renowned of the entire Russian symbolist movement. Alexander Blok is widely considered to be one of the leading Russian poets of the twentieth century. He was often compared with Alexander Pushkin, and the whole Silver Age of Russian Poetry was sometimes styled the "Age of Blok." His early verse is impeccably musical and rich in sound. Later, he sought to introduce daring rhythmic patterns and uneven beats into his poetry. His mature poems are often based on the conflict between the Platonic vision of ideal beauty and the disappointing reality of foul industrial outskirts. They are often characterized by an idiosyncratic use of color and spelling to express meaning. One of Blok's most famous and controversial poems was "The Twelve," which described the march of twelve Bolshevik soldiers through the streets of revolutionary Petrograd in pseudo-religious terms.

Andrei Bely strove to forge a unity of prose, poetry, and music in much of his literature, as evidenced by the title of one of his early works, Symphonies in Prose. However, his fame rests primarily on post-symbolist works such as celebrated modernist novel Petersburg (1911-1913), a philosophical and spiritual work featuring a highly unorthodox narrative style, fleeting allusions and distinctive rhythmic experimentation. Vladimir Nabokov placed it second in his list of the greatest novels of the twentieth century after James Joyce's Ulysses. Other works worthy of mention include the highly influential theoretical book of essays Symbolism (1910), which was instrumental in redefining the goals of the symbolist movement, and the novel Kotik Letaev (1914-1916), which traces the first glimpses of consciousness in a new-born baby.

The city of St. Petersburg itself became one of the major symbols utilized by the second generation of Russian symbolists. Blok's verses on the imperial capital bring to life an impressionistic picture of the "city of a thousand illusions"[This quote needs a citation] and as a doomed world full of merchants and bourgeois figures. Various elemental forces (such as sunrises and sunsets, light and darkness, lightning and fire) assume apocalyptic qualities, serving as portents of a cataclysmic event that would change the earth and humanity forever. The Scythians and Mongols were often found in the works of these poets, serving as symbols of future catastrophic wars. Due to the eschatological tendency inherent in the Russian symbolist movement, many of them—including Blok, Bely, and Bryusov—accepted the Russian Revolution as the next evolutionary step in their nation's history.

Decline of the movement

Russian symbolism had begun to lose its momentum in literature by the 1910s as many younger poets were drawn to the acmeist movement, which distanced itself from excesses of symbolism, or joined the futurists, an iconoclastic group which sought to recreate art entirely, eschewing all aesthetic conventions.

Despite intense disapproval by the Soviet State, however, Symbolism continued to be an influence on Soviet dissident poets like Boris Pasternak. In the Literary Gazette of September 9, 1958, the critic Viktor Pertsov denounced, "the decadent religious poetry of Pasternak, which reeks of mothballs from the Symbolist suitcase of 1908-10 manufacture."[4]

More recently, Robert Bird has been less critical than the Literary Gazette, "Nomenclature notwithstanding, Russian Symbolism owed far less to French Symbolism (with which, according to Ivanov, it shared 'neither a historical no ideological basis') than it did to German Romanticism and to the great poets and prose writers of nineteenth-century Russia. It was not so much an artistic movement as a comprehensive worldview, an attempt to give aesthetics a spiritual foundation. The Russian Symbolists sought to preserve the insights and achievements of past civilisations and to build upon them. They viewed human creativity as a continuum, celebrating 'Symbolist' tendencies in the art and culture of civilisations distant both temporally and spatially... According to Symbolist conviction, divisions between various fields of knowledge and artistic disciplines were artificial: poetry was intimately linked not only to painting, music, and drama, but also to philosophy, psychology, religion, and myth. The intellectual cross fertilization that took place at Ivanov's 'Tower', in short, was a social manifestation of Symbolist tenets."[5]

Visual arts

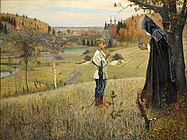

Probably the most important Russian symbolist painter was Mikhail Vrubel, who achieved fame with a large mosaic-like canvas The Demon Seated (1890) and went mad while working on the dynamic and sinister The Demon Downcast (1902).

Other symbolist painters associated with the World of Art magazine were Victor Borisov-Musatov and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, followers of Puvis de Chavannes; Mikhail Nesterov, who painted religious subjects from medieval Russian history; Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, with his "urbanistic phantasms", and Nicholas Roerich, whose paintings have been described as hermetic, or esoteric. The tradition of Russian symbolism in the late Soviet period was renewed by Konstantin Vasilyev, whose style was greatly influenced by the Russian Neo-romantic painter Viktor Vasnetsov, as well as Mikhail Nesterov and Nicholas Roerich.

Music and theatre

The foremost symbolist composer was Alexander Scriabin who in his First Symphony praised art as a kind of religion. Le Divin Poème (1902-1904) sought to express "the evolution of the human spirit from pantheism to unity with the universe."[This quote needs a citation] Prométhée (1910), given in 1915 in New York City, was accompanied by elaborately selected colour projections on a screen.

In Scriabin's synthetic performances music, poetry, dancing, colours, and scents were used so as to bring about "supreme, final ecstasy."[This quote needs a citation] Andrey Bely and Wassily Kandinsky articulated similar ideas on the "stage fusion of all arts."[This quote needs a citation]

As to more traditional theatre, Paul Schmidt an influential translator, has written that The Cherry Orchard and some other late plays of Anton Chekhov show the influence of the Symbolist movement.[6] Their first production by Constantin Stanislavski was as realistic as possible. Stanislavski collaborated with the English theatre practitioner Edward Gordon Craig on a significant production of Hamlet in 1911–12, which experimented with symbolist monodrama as a basis for its staging. Two years later, Stanislavski won international acclaim when he staged Maurice Maeterlinck's The Blue Bird in the Moscow Art Theatre.

Nikolai Evreinov was one of a number of writers who developed a symbolist theory of theatre. Evreinov insisted that everything around us is "theatre" and that nature is full of theatrical conventions, for example, desert flowers mimicking stones, mice feigning death in order to escape cats' claws, and the complicated dances of some birds. Theatre, for Evreinov, was a universal symbol of existence.

References

- ^ Peterson 1993.

- ^ a b "Symbolism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- ^ a b Waegemans, E. (2016). History of Russian Literature Since Peter the Great 1700-2000 (Revised edition. ed.). Antwerp: Publisher Vrijdag.

- ^ Olga Ivinskaya (1978), A Captive of Time: My Years with Pasternak, page 231.

- ^ Viacheslav Ivanov (2003), Selected Essays, Northwestern University Press. Page xi.

- ^ The Plays of Anton Chekhov, trans. Paul Schmidt (1997)

Bibliography

- Friedman, Julia. Beyond Symbolism and Surrealism: Alexei Remizov's Synthetic Art, Northwestern University Press, 2010. ISBN 0-8101-2617-6 (Trade Cloth)

- Peterson, Ronald E. (1993). A History of Russian Symbolism. Amsterdam; Philadelphia, Pa: John Benjamins Pub. ISBN 90-272-1534-0.

- Articles with short description

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Articles with unsourced quotes

- Articles containing French-language text

- Articles containing German-language text

- Articles containing Dutch-language text

- Russian symbolism

- Russian art movements

- Russian literary movements

- Symbolism (arts)

- Modernist theatre