Prednisone

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Deltasone, Liquid Pred, Orasone, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Glucocorticoid[1] |

| Main uses | Asthma, COPD, rheumatologic diseases[1] |

| Side effects | Cataracts, bone loss, easy bruising, muscle weakness, thrush[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 10 mg[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601102 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 70% |

| Metabolism | prednisolone (liver) |

| Elimination half-life | 3 to 4 hours in adults. 1 to 2 hours in children[3] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H26O5 |

| Molar mass | 358.434 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 230 °C (446 °F) |

| |

| |

Prednisone is a glucocorticoid medication mostly used to suppress the immune system and decrease inflammation in conditions such as asthma, COPD, and rheumatologic diseases.[1] It is also used to treat high blood calcium due to cancer and adrenal insufficiency along with other steroids.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects with long term use include cataracts, bone loss, easy bruising, muscle weakness, and thrush.[1] Other side effects include weight gain, swelling, high blood sugar, increased risk of infection, and psychosis.[4][1] It is generally considered safe in pregnancy and low doses appear to be safe when breastfeeding.[5] After prolonged use, prednisone needs to be stopped gradually.[1]

Prednisone must be converted to prednisolone by the liver before it becomes active.[6][7] Prednisolone then binds to glucocorticoid receptors, activating them and triggering changes in gene expression.[4]

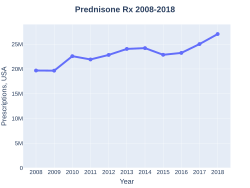

Prednisone was patented in 1954 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1955.[1][8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines as an alternative to prednisolone.[9] It is available as a generic medication.[1] In the United States, the wholesale cost per dose was less than US$0.30 in 2018.[10] In 2017, it was the 22nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 25 million prescriptions.[11][12]

Medical uses

Prednisone is used for many different autoimmune diseases and inflammatory conditions, including asthma, gout, COPD, CIDP, rheumatic disorders, allergic disorders, ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, adrenocortical insufficiency, hypercalcemia due to cancer, thyroiditis, laryngitis, severe tuberculosis, hives, lipid pneumonitis, pericarditis, multiple sclerosis, nephrotic syndrome, sarcoidosis, to relieve the effects of shingles, lupus, myasthenia gravis, poison oak exposure, Ménière's disease, autoimmune hepatitis, giant-cell arteritis, the Herxheimer reaction that is common during the treatment of syphilis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, uveitis, and as part of a drug regimen to prevent rejection after organ transplant.[13][14][15]

Prednisone has also been used in the treatment of migraine headaches and cluster headaches and for severe aphthous ulcer.[16] Prednisone is used as an antitumor drug.[17] It is important in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, Hodgkin's lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and other hormone-sensitive tumors, in combination with other anticancer drugs.

Prednisone can be used in the treatment of decompensated heart failure to increase renal responsiveness to diuretics, especially in heart failure patients with refractory diuretic resistance with large dose of loop diuretics.[18][19][20][21][22][23] In terms of the mechanism of action for this purpose: prednisone, a glucocorticoid, can improve renal responsiveness to atrial natriuretic peptide by increasing the density of natriuretic peptide receptor type A in the renal inner medullary collecting duct, thereby inducing a potent diuresis.[24]

At high doses it may be used to prevent rejection following organ transplant.[1]

-

Ulcerated plaque at 5 weeks after re-excision of the biopsy scar.

-

Healing lesion after 1 month of prednisone therapy.

Dosage

The initial dose in adults is often 20 to 70 mg which is decreased to 2 to 15 mg if long term use is needed.[25] In children an initial dose of 0.5 to 2 mg/kg may be used which is decreased to 0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg if long term use is needed.[25]

The defined daily dose is 10 mg.[2]

Side effects

Short-term side effects, as with all glucocorticoids, include high blood glucose levels (especially in patients with diabetes mellitus or on other medications that increase blood glucose, such as tacrolimus) and mineralocorticoid effects such as fluid retention.[26] The mineralocorticoid effects of prednisone are minor, which is why it is not used in the management of adrenal insufficiency, unless a more potent mineralocorticoid is administered concomitantly.

It can also cause depression or depressive symptoms and anxiety in some individuals.[27][28]

Long-term side effects include Cushing's syndrome, steroid dementia syndrome,[29] truncal weight gain, osteoporosis, glaucoma and cataracts, diabetes mellitus type 2, and depression upon dose reduction or cessation.[30] Prednisone also results in leukocytosis.[31]

Major

- Steroid myopathy

- Increased blood sugar for individuals with diabetes

- Difficulty controlling emotion

- Difficulty in maintaining train of thought

- Weight gain

- Immunosuppression

- Corticosteroid-induced lipodystrophy (moon face, central obesity)

- Depression, mania, psychosis, or other psychiatric symptoms

- Unusual fatigue or weakness

- Mental confusion / indecisiveness

- Memory and attention dysfunction (steroid dementia syndrome)

- Muscle atrophy[32]

- Blurred vision

- Abdominal pain

- Peptic ulcer

- Painful hips or shoulders

- Steroid-induced osteoporosis

- Stretch marks

- Osteonecrosis – same as avascular necrosis

- Insomnia

- Severe joint pain

- Cataracts or glaucoma

- Anxiety

- Black stool

- Stomach pain or bloating

- Severe swelling

- Mouth sores or dry mouth

- Avascular necrosis

- Hepatic steatosis

Minor

- Nervousness

- Acne

- Skin rash

- Appetite gain

- Hyperactivity

- Increased thirst

- Frequent urination

- Diarrhea

- Reduced intestinal flora

- Leg pain/cramps

- Sensitive teeth

- Headache

- Induced vomiting

Dependency

Adrenal suppression will begin to occur if prednisone is taken for longer than seven days. Eventually, this may cause the body to temporarily lose the ability to manufacture natural corticosteroids (especially cortisol), which results in dependence on prednisone. For this reason, prednisone should not be abruptly stopped if taken for more than seven days; instead, the dosage should be gradually reduced. This weaning process may be over a few days if the course of prednisone was short, but may take weeks or months[33] if the patient had been on long-term treatment. Abrupt withdrawal may lead to an Addison crisis. For those on chronic therapy, alternate-day dosing may preserve adrenal function and thereby reduce side effects.[34]

Glucocorticoids act to inhibit feedback of both the hypothalamus, decreasing corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), and corticotrophs in the anterior pituitary gland, decreasing the amount of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). For this reason, glucocorticoid analogue drugs such as prednisone down-regulate the natural synthesis of glucocorticoids. This mechanism leads to dependence in a short time and can be dangerous if medications are withdrawn too quickly. The body must have time to begin synthesis of CRH and ACTH and for the adrenal glands to begin functioning normally again.

Prednisone may start to result in the suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis if used at doses 7–10 mg or higher for several weeks. This is approximately equal to the amount of endogenous cortisol produced by the body every day. As such, the HPA axis starts to become suppressed and atrophy. If this occurs the people should be tapered off prednisone slowly to give the adrenal gland enough time to regain its function and endogenous production of steroids. Supplemental doses, or "stress doses" may be required in those with HPA axis suppression who are experiencing a higher degree of stress (e.g., illness, surgery, trauma, etc.). Failing to do so in such situations could be life-threatening.[citation needed]

Withdrawal

The magnitude and speed of dose reduction in corticosteroid withdrawal should be determined on a case-by-case basis, taking into consideration the underlying condition being treated, and individual patient factors such as the likelihood of relapse and the duration of corticosteroid treatment. Gradual withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids should be considered in those whose disease is unlikely to relapse and have:

- received more than 40 mg prednisone (or equivalent) daily for more than 1 week

- been given repeat doses in the evening

- received more than 3 weeks of treatment

- recently received repeated courses (particularly if taken for longer than 3 weeks)

- taken a short course within 1 year of stopping long-term therapy

- other possible causes of adrenal suppression

Systemic corticosteroids may be stopped abruptly in those whose disease is unlikely to relapse and who have received treatment for 3 weeks or less and who are not included in the patient groups described above.

During corticosteroid withdrawal, the dose may be reduced rapidly down to physiological doses (equivalent to prednisolone 7.5 mg daily) and then reduced more slowly. Assessment of the disease may be needed during withdrawal to ensure that relapse does not occur.[35]

Pharmacology

Prednisone is a synthetic glucocorticoid used for its anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties.[37][38] Prednisone is a prodrug; it is metabolised in the liver by 11-β-HSD to prednisolone, the active drug. Prednisone has no substantial biological effects until converted via hepatic metabolism to prednisolone.[39]

Pharmacokinetics

Prednisone is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and has a half life of 2–3 hours.[38] it has a volume of distribution of 0.4–1 L/kg.[40] The drug is cleared by hepatic metabolism using cytochrome P450 enzymes. Metabolites are excreted in the bile and urine.[40]

Industry

The pharmaceutical industry uses prednisone tablets for the calibration of dissolution testing equipment according to the United States Pharmacopeia (USP).

Chemistry

Prednisone is a synthetic pregnane corticosteroid and derivative of cortisone and is also known as δ1-cortisone or 1,2-dehydrocortisone or as 17α,21-dihydroxypregna-1,4-diene-3,11,20-trione.[41][42]

History

The first isolation and structure identifications of prednisone and prednisolone were done in 1950 by Arthur Nobile.[43][44][45] The first commercially feasible synthesis of prednisone was carried out in 1955 in the laboratories of Schering Corporation, which later became Schering-Plough Corporation, by Arthur Nobile and coworkers.[46] They discovered that cortisone could be microbiologically oxidized to prednisone by the bacterium Corynebacterium simplex. The same process was used to prepare prednisolone from hydrocortisone.[47]

The enhanced adrenocorticoid activity of these compounds over cortisone and hydrocortisone was demonstrated in mice.[47]

Prednisone and prednisolone were introduced in 1955 by Schering and Upjohn, under the brand names Meticorten[48] and Delta-Cortef,[49] respectively. These prescription medicines are now available from a number of manufacturers as generic drugs.

Society and culture

Cost

In the United States, the wholesale cost per dose was less than US$0.30 in 2018.[10] In 2017, it was the 22nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 25 million prescriptions.[11][12]

-

Prednisone costs (US)

-

Prednisone prescriptions (US)

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 "Prednisone Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2018. Archived 22 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020. Archived 2 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Pickup ME (1979). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of prednisone and prednisolone". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 4 (2): 111–28. doi:10.2165/00003088-197904020-00004. PMID 378499.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Brunton, Laurence (2017). Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics (13 ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 739, 746, 1237. ISBN 978-1-25-958473-2.

- ↑ "Prednisone Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2018. Archived 22 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Product Information Panafcort (prednisone) Panafcortelone (prednisolone)" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. St Leonards, Australia: Aspen Pharmacare Australia Pty Ltd. 11 July 2017. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018. Archived 30 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Buttgereit F, Gibofsky A (June 2013). "Delayed-release prednisone - a new approach to an old therapy". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 14 (8): 1097–106. doi:10.1517/14656566.2013.782001. PMID 23594208.

- ↑ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 485. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2018. Archived 13 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "NADAC as of 2018-12-19". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018. Archived 2018-12-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020. Archived 12 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Prednisone - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. 1 December 1981. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020. Archived 12 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Autoimmune Hepatitis~treatment at eMedicine

- ↑ "Corticosteroids". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. NCBI Bookshelf. 30 May 2014. PMID 31643719. NBK548400. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2020. Archived 23 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Prednisone". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2011. Archived 22 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Wackym, P. Ashley; Snow, James B. (2017). Ballenger's Otorhinolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. PMPH USA. p. 1185. ISBN 9781607951773. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ↑ "Antineoplastic Agents, Hormonal". Medical Subject Headings. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2010. Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Riemer AD (April 1958). "Application of the newer corticosteroids to augment diuresis in congestive heart failure". The American Journal of Cardiology. 1 (4): 488–96. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(58)90120-6. PMID 13520608.

- ↑ Newman DA (February 1959). "Reversal of intractable cardiac edema with prednisone". New York State Journal of Medicine. 59 (4): 625–33. PMID 13632954.

- ↑ Zhang H, Liu C, Ji Z, Liu G, Zhao Q, Ao YG, Wang L, Deng B, Zhen Y, Tian L, Ji L, Liu K (September 2008). "Prednisone adding to usual care treatment for refractory decompensated congestive heart failure". International Heart Journal. 49 (5): 587–95. doi:10.1536/ihj.49.587. PMID 18971570.

- ↑ Liu C, Liu G, Zhou C, Ji Z, Zhen Y, Liu K (September 2007). "Potent diuretic effects of prednisone in heart failure patients with refractory diuretic resistance". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 23 (11): 865–8. doi:10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70840-1. PMC 2651362. PMID 17876376.

- ↑ Liu C, Chen H, Zhou C, Ji Z, Liu G, Gao Y, Tian L, Yao L, Zheng Y, Zhao Q, Liu K (October 2006). "Potent potentiating diuretic effects of prednisone in congestive heart failure". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 48 (4): 173–6. doi:10.1097/01.fjc.0000245242.57088.5b. PMID 17086096.

- ↑ Massari F, Mastropasqua F, Iacoviello M, Nuzzolese V, Torres D, Parrinello G (March 2012). "The glucocorticoid in acute decompensated heart failure: Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde?". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 30 (3): 517.e5–10. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2011.01.023. PMID 21406321.

- ↑ Liu C, Chen Y, Kang Y, Ni Z, Xiu H, Guan J, Liu K (October 2011). "Glucocorticoids improve renal responsiveness to atrial natriuretic peptide by up-regulating natriuretic peptide receptor-A expression in the renal inner medullary collecting duct in decompensated heart failure". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 339 (1): 203–9. doi:10.1124/jpet.111.184796. PMID 21737535. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2019. Archived 29 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "PREDNISOLONE and PREDNISONE oral - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2020. Archived 29 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "Prednisone and other corticosteroids: Balance the risks and benefits - Mayo Clinic". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 2017-04-07. Archived 2017-05-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Prednisone Information". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2018. Archived 20 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Prednisone". MedlinePlus Drug Information. Archived from the original on 5 July 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2018. Archived 5 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Wolkowitz OM, Lupien SJ, Bigler ED (June 2007). "The "steroid dementia syndrome": a possible model of human glucocorticoid neurotoxicity". Neurocase. 13 (3): 189–200. doi:10.1080/13554790701475468. PMID 17786779.

- ↑ "Steroids". Australian Department of Health & Human Services. April 2016. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 2018-06-14. Archived 2018-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Miller, Neil R.; Walsh, Frank Burton; Hoyt, William Fletcher (2005). Walsh and Hoyt's Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1062. ISBN 9780781748117. Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2019. Archived 13 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Schakman O, Gilson H, Kalista S, Thissen JP (November 2009). "Mechanisms of muscle atrophy induced by glucocorticoids". Hormone Research. 72 (Suppl. 1): 36–41. doi:10.1159/000229762. PMID 19940494.

- ↑ "Steroid Drug Withdrawal Symptoms, Treatment & Prognosis". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 2018-06-14. Archived 2018-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Bello, CS; Garrett, SD. "Therapeutic and Adverse Effects of Glucocorticoids". U.S. Pharmacist Continuing Education Program. Archived from the original on 2008-07-11. Archived 2008-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Iliopoulou, Amalia; Abbas, Afroze; Murray, Robert (2013-05-19). "How to manage withdrawal of glucocorticoid therapy". Prescriber. 24 (10): 23–29. doi:10.1002/psb.1060.

- ↑ "Glucocorticoid Pathway , Pharmacodynamics". PharmGKB. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ↑ Becker, DE (Spring 2013). "Basic and clinical pharmacology of glucocorticosteroids". Anesthesia Progress. 60 (1): 25–32. doi:10.2344/0003-3006-60.1.25. PMC 3601727. PMID 23506281.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Prednisone". DrugBank. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 2019-01-29. Archived 2019-01-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Prednisone". MedlinePlus. NIH U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019. Archived 9 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Schijvens, Anne M.; ter Heine, Rob; de Wildt, Saskia N.; Schreuder, Michiel F. (16 March 2018). "Pharmacology and pharmacogenetics of prednisone and prednisolone in patients with nephrotic syndrome". Pediatric Nephrology. 34 (3): 389–403. doi:10.1007/s00467-018-3929-z. PMID 29549463.

- ↑ J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 1013–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ↑ Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 871–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ↑ Wainwright M (1998). "The secret of success: Arthur Nobile's discovery of the steroids prednisone and prednisolone in the 1950s revolutionised the treatment of arthritis". Chemistry in Britain. 34 (1): 46. OCLC 106716069.

- ↑ "Inventor Profile: Arthur Nobile". National Inventors Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012. Archived 12 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Arthur Nobile". New Jersey Inventors Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 1 September 2011. Archived 1 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Merck Index (14th ed.). Merck & Co. Inc. 2006. p. 1327. ISBN 978-0-911910-00-1.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Herzog HL, Nobile A, Tolksdorf S, Charney W, Hershberg EB, Perlman PL, Pechet MM (February 1955). "New antiarthritic steroids". Science. 121 (3136): 176. doi:10.1126/science.121.3136.176. PMID 13225767.

- ↑ "Meticorten: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2018. Archived 28 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Delta-Cortef: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2018. Archived 28 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- The National Center for Biotechnology Information: Prednisone Archived 20 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- National Inventors Hall of Fame induction of Arthur Nobile

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2019

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Appetite stimulants

- Glucocorticoids

- Mineralocorticoids

- Prodrugs

- Antiasthmatic drugs

- Triketones

- RTT

- World Health Organization essential medicines (alternatives)