Potomac River

| Potomac River | |

|---|---|

| |

The Potomac River watershed covers the District of Columbia and parts of four states. | |

| Native name | Patawomeck (Algonquian languages) |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | West Virginia, Maryland, Virginia, District of Columbia |

| Cities | Cumberland, MD; Harpers Ferry, WV; Washington, D.C.; Alexandria, VA |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | North Branch |

| • location | Fairfax Stone, Preston County, West Virginia |

| • coordinates | 39°11′43″N 79°29′28″W / 39.19528°N 79.49111°W |

| • elevation | 3,060 ft (930 m) |

| 2nd source | South Branch |

| • location | Near Monterey, Highland County, Virginia |

| • coordinates | 38°25′30″N 79°36′27″W / 38.425°N 79.6075°W |

| Source confluence | |

| • location | Green Spring, West Virginia |

| • coordinates | 39°31′39″N 78°35′15″W / 39.5275°N 78.5875°W |

| Mouth | Chesapeake Bay |

• location | St. Mary's County, Maryland/Northumberland County, Virginia, United States |

• coordinates | 38°00′00″N 76°20′06″W / 38°N 76.335°W |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 405 mi (652 km) |

| Basin size | 14,700 sq mi (38,000 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Little Falls, near Washington, D.C. (non-tidal; water years: 1931–2018)[2] |

| • average | 11,498 cu ft/s (325.6 m3/s) (1931–2018) |

| • minimum | 4,017 cu ft/s (113.7 m3/s) (2002) |

| • maximum | 484,000 cu ft/s (13,700 m3/s) (1936) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Point of Rocks, Maryland |

| • average | 9,504 cu ft/s (269.1 m3/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Hancock, Maryland |

| • average | 4,168 cu ft/s (118.0 m3/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Paw Paw, West Virginia |

| • average | 3,376 cu ft/s (95.6 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Conococheague Creek, Antietam Creek, Monocacy River, Rock Creek, Anacostia River |

| • right | Cacapon River, Shenandoah River, Goose Creek, Occoquan River, Wicomico River |

| Waterfalls | Great Falls, Little Falls |

Note: Since 1996, the Potomac has been the 'sister river' of the Ara River of Tokyo, Japan[3] | |

The Potomac River (/pəˈtoʊmək/ ) is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States that flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is 405 miles (652 km) long,[4] with a drainage area of 14,700 square miles (38,000 km2),[5] and is the fourth-largest river along the East Coast of the United States.[citation needed] More than 6 million people live within its watershed.[6]

The river forms part of the borders between Maryland and Washington, D.C., on the left descending bank, and West Virginia and Virginia on the right descending bank. Except for a small portion of its headwaters in West Virginia, the North Branch Potomac River is considered part of Maryland to the low-water mark on the opposite bank. The South Branch Potomac River lies completely within the state of West Virginia except for its headwaters, which lie in Virginia. All navigable parts of the river were designated as a National Recreation Trail in 2006,[7] and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration designated an 18-square-mile (47 km2) portion of the river in Charles County, Maryland, as the Mallows Bay–Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary in 2019.[8]

The river has significant historical and political significance, as the nation's capital of Washington, D.C. is located on its banks, as is Mount Vernon, the home of "Father of his Country" George Washington. During the American Civil War, the river became the boundary between the Union and the Confederacy, and the Union's largest army, the Army of the Potomac, was named after the river.

Course

The Potomac River runs 405 mi (652 km) from Fairfax Stone Historical Monument State Park in West Virginia on the Allegheny Plateau to Point Lookout, Maryland, and drains 14,679 sq mi (38,020 km2). The length of the river from the junction of its North and South Branches to Point Lookout is 302 mi (486 km).[4]

The river has two sources. The source of the North Branch is at the Fairfax Stone located at the junction of Grant, Tucker, and Preston counties in West Virginia. The source of the South Branch is located near Hightown in northern Highland County, Virginia. The river's two branches converge just east of Green Spring in Hampshire County, West Virginia, to form the Potomac. As it flows from its headwaters down to the Chesapeake Bay, the Potomac traverses five geological provinces: the Appalachian Plateau, the Ridge and Valley, the Blue Ridge, the Piedmont Plateau, and the Atlantic coastal plain.

Once the Potomac drops from the Piedmont to the Coastal Plain at the Atlantic Seaboard fall line at Little Falls, tides further influence the river as it passes through Washington, D.C., and beyond. Salinity in the Potomac River Estuary increases thereafter with distance downstream. The estuary also widens, reaching 11 statute miles (17 km) wide at its mouth, between Point Lookout, Maryland, and Smith Point, Virginia, before flowing into the Chesapeake Bay.

North Branch Potomac River

The source of the North Branch Potomac River is at the Fairfax Stone located at the junction of Grant, Tucker and Preston counties in West Virginia. From the Fairfax Stone, the North Branch Potomac River flows 27 mi (43 km) to the man-made Jennings Randolph Lake, an impoundment designed for flood control and emergency water supply. Below the dam, the North Branch cuts a serpentine path through the eastern Allegheny Mountains. First, it flows northeast by the communities of Bloomington, Luke, and Westernport in Maryland and then on by Keyser, West Virginia to Cumberland, Maryland. At Cumberland, the river turns southeast. 103 miles (166 km) downstream from its source,[4] the North Branch is joined by the South Branch between Green Spring and South Branch Depot, West Virginia from whence it flows past Hancock, Maryland and turns southeast once more on its way toward Washington, D.C., and the Chesapeake Bay.

South Branch Potomac River

The exact location of the South Branch's source is northwest of Hightown along U.S. Route 250 on the eastern side of Lantz Mountain (3,934 ft) in Highland County. From Hightown, the South Branch is a small meandering stream that flows northeast along Blue Grass Valley Road through the communities of New Hampden and Blue Grass. At Forks of Waters, the South Branch joins with Strait Creek and flows north across the Virginia/West Virginia border into Pendleton County.

The river then travels on a northeastern course along the western side of Jack Mountain (4,045 ft), followed by Sandy Ridge (2,297 ft) along U.S. Route 220. North of the confluence of the South Branch with Smith Creek, the river flows along Town Mountain (2,848 ft) around Franklin at the junction of U.S. Route 220 and U.S. Route 33. After Franklin, the South Branch continues north through the Monongahela National Forest to Upper Tract where it joins with three sizeable streams: Reeds Creek, Mill Run, and Deer Run.

Between Big Mountain (2,582 ft) and Cave Mountain (2,821 ft), the South Branch bends around the Eagle Rock (1,483 ft) outcrop and continues its flow northward into Grant County. Into Grant, the South Branch follows the western side of Cave Mountain through the 20-mile (32 km) long Smoke Hole Canyon, until its confluence with the North Fork at Cabins, where it flows east to Petersburg. At Petersburg, the South Branch Valley Railroad begins, which parallels the river until its mouth at Green Spring.

In its eastern course from Petersburg into Hardy County, the South Branch becomes more navigable allowing for canoes and smaller river vessels. The river splits and forms a series of large islands while it heads northeast to Moorefield. At Moorefield, the South Branch is joined by the South Fork South Branch Potomac River and runs north to Old Fields where it is fed by Anderson Run and Stony Run.

At McNeill, the South Branch flows into the Trough where it is bound to its west by Mill Creek Mountain (2,119 ft) and to its east by Sawmill Ridge (1,644 ft). This area is the habitat to bald eagles. The Trough passes into Hampshire County and ends at its confluence with Sawmill Run south of Glebe and Sector.

The South Branch continues north parallel to South Branch River Road (County Route 8) toward Romney with a number of historic plantation farms adjoining it. En route to Romney, the river is fed by Buffalo Run, Mill Run, McDowell Run, and Mill Creek at Vanderlip. The South Branch is traversed by the Northwestern Turnpike (U.S. Route 50) and joined by Sulphur Spring Run where it forms Valley View Island to the west of town.

Flowing north of Romney, the river still follows the eastern side of Mill Creek Mountain until it creates a horseshoe bend at Wappocomo's Hanging Rocks around the George W. Washington plantation, Ridgedale. To the west of Three Churches on the western side of South Branch Mountain, 3,028 feet (923 m), the South Branch creates a series of bends and flows to the northeast by Springfield through Blue's Ford. After two additional horseshoe bends (meanders), the South Branch flows under the old Baltimore and Ohio Railroad mainline between Green Spring and South Branch Depot, and joins the North Branch to form the Potomac.

Upper Potomac River

This stretch encompasses the section of the Potomac River from the confluence of its North and South Branches through Opequon Creek near Shepherdstown, West Virginia.[10] Along the way the following tributaries drain into the Potomac: North Branch Potomac River, South Branch Potomac River, Town Creek, Little Cacapon River, Sideling Hill Creek, Cacapon River, Sir Johns Run, Warm Spring Run, Tonoloway Creek, Fifteenmile Creek, Sleepy Creek, Cherry Run, Back Creek, Conococheague Creek, and Opequon Creek.

Lower Potomac River

This section covers the Potomac from just above Harpers Ferry in West Virginia down to Little Falls, Maryland on the border between Maryland and Washington, DC. Along the way the following tributaries drain into the Potomac: Antietam Creek, Shenandoah River, Catoctin Creek (Virginia), Catoctin Creek (Maryland), Tuscarora Creek, Monocacy River, Little Monocacy River, Broad Run, Goose Creek, Broad Run, Horsepen Branch, Little Seneca Creek, Tenmile Creek, Great Seneca Creek, Old Sugarland Run, Muddy Branch, Nichols Run, Watts Branch, Limekiln Branch, Carroll Branch, Pond Run, Clarks Branch, Mine Run Branch, Difficult Run, Bullneck Run, Rock Run, Scott Run, Dead Run, Turkey Run, Cabin John Creek, Minnehaha Branch, and Little Falls Branch.

Tidal Potomac River

The Tidal Potomac River lies below the Fall Line. This 108-mile (174-km) stretch encompasses the Potomac from a short distance below the Washington, DC - Montgomery County line, just downstream of the Little Falls of the Potomac River, to the Chesapeake Bay.[11] Along the way the following tributaries drain into the Potomac: Pimmit Run, Gulf Branch, Donaldson Run, Windy Run, Spout Run, Maddox Branch, Foundry Branch, Rock Creek, Rocky Run, Tiber Creek, Roaches Run, Washington Channel, Anacostia River, Four Mile Run, Oxon Creek, Hunting Creek, Broad Creek, Henson Creek, Swan Creek, Piscataway Creek, Little Hunting Creek, Dogue Creek, Accotink Creek, Pohick Creek, Pomonkey Creek, Occoquan River, Neabsco Creek, Powell's Creek, Mattawoman Creek, Chicamuxen Creek, Quantico Creek, Little Creek, Chopawamsic Creek, Tank Creek, Aquia Creek, Potomac Creek, Nanjemoy Creek, Chotank Creek, Port Tobacco River, Popes Creek, Gambo Creek, Clifton Creek, Piccowaxen Creek, Upper Machodoc Creek, Wicomico River, Cobb Island, Monroe Creek, Mattox Creek, Popes Creek, Breton Bay, Leonardtown, St. Marys River, Yeocomico River, Coan River, and Hull Creek.

History

Natural history

The river itself is at least 3.5 million years old,[9] likely extending back ten to twenty million years before the present when the Atlantic Ocean lowered and exposed coastal sediments along the fall line. This included the area at Great Falls, which eroded into its present form during recent glaciation periods.[12]

The stream gradient of the entire river is 0.14%, a drop of 930 m over 652 km.

Human history

"Potomac" is a European spelling of Patawomeck, the Algonquian name of a Native American village on its southern bank.[13] Native Americans had different names for different parts of the river, calling the river above Great Falls Cohongarooton, meaning "honking geese"[14][15] and "Patawomke" below the Falls, meaning "river of swans".[16] In 1608, Captain John Smith explored the river now known as the Potomac and made drawings of his observations which were later compiled into a map and published in London in 1612. This detail from that map shows his rendition of the river that the local tribes had told him was called the "Patawomeck". The spelling of the name has taken many forms over the years from "Patawomeck" (as on Captain John Smith's map) to "Patomake", "Patowmack", and numerous other variations in the 18th century and now "Potomac".[15] The river's name was officially decided upon as "Potomac" by the Board on Geographic Names in 1931.[17]

The similarity of the name to the Ancient Greek word for river, potamos, has been noted for more than two centuries but it appears to be due to chance.[19][20][21]

The Potomac River brings together a variety of cultures throughout the watershed from the coal miners of upstream West Virginia to the urban residents of the nation's capital and, along the lower Potomac, the watermen of Virginia's Northern Neck.

Top row: Chain Bridge (two views) and Pimmit Run Bridge; Bottom Row: Aqueduct Bridget {two views) and Georgetown Ferry

Being situated in an area rich in American history and American heritage has led to the Potomac being nicknamed "the Nation's River". George Washington, the first President of the United States, was born in, surveyed, and spent most of his life within, the Potomac basin. All of Washington, D.C., the nation's capital city, also lies within the watershed. The First United States Congress by act of July 16, 1790 stated that the nation's capital was to be located on the river.[22] The 1859 siege of Harper's Ferry at the river's confluence with the Shenandoah was a precursor to numerous epic battles of the American Civil War in and around the Potomac and its tributaries, such as the 1861 Battle of Ball's Bluff and the 1862 Battle of Shepherdstown.

General Robert E. Lee crossed the river, thereby invading the North and threatening Washington, D.C., twice in campaigns climaxing in the battles of Antietam (September 17, 1862) and Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863). Confederate General Jubal Early crossed the river in July 1864 on his attempted raid on the nation's capital. The river not only divided the Union from the Confederacy, but also gave name to the Union's largest army, the Army of the Potomac.[23] The Patowmack Canal was intended by George Washington to connect the Tidewater region near Georgetown with Cumberland, Maryland. Started in 1785 on the Virginia side of the river, it was not completed until 1802. Financial troubles led to the closure of the canal in 1830. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal operated along the banks of the Potomac in Maryland from 1831 to 1924 and also connected Cumberland to Washington, D.C.[24] This allowed freight to be transported around the rapids known as the Great Falls of the Potomac River, as well as many other, smaller rapids.

Washington, D.C. began using the Potomac as its principal source of drinking water with the opening of the Washington Aqueduct in 1864, using a water intake constructed at Great Falls.[25][26]

Hydrology

Water supply and water quality

An average of approximately 486 million US gallons (1,840,000 m3) of water is withdrawn daily from the Potomac in the Washington area for water supply, providing about 78 percent of the region's total water usage, this amount includes approximately 80 percent of the drinking water consumed by the region's estimated 6.1 million residents.[5][27]

As a result of damaging floods in 1936 and 1937,[28] the Army Corps of Engineers proposed the Potomac River basin reservoir projects, a series of dams that were intended to regulate the river and to provide a more reliable water supply. One dam was to be built at Little Falls, just north of Washington, backing its pool up to Great Falls. Just above Great Falls, the much larger Seneca Dam was proposed whose reservoir would extend to Harpers Ferry.[29] Several other dams were proposed for the Potomac and its tributaries.

| Dams on the Potomac River |

|---|

|

When detailed studies were issued by the Corps in the 1950s, they met sustained opposition, led by U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, resulting in the plans' abandonment.[33] The only dam project that did get built was Jennings Randolph Lake on the North Branch.[34] The Corps built a supplementary water intake for the Washington Aqueduct at Little Falls in 1959.[35]

In 1940 Congress passed a law authorizing the creation of an interstate compact to coordinate water quality management among states in the Potomac basin. Maryland, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the District of Columbia agreed to establish the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin. The compact was amended in 1970 to include coordination of water supply issues and land use issues related to water quality.[36]

Beginning in the 19th century, with increasing mining and agriculture upstream and urban sewage and runoff downstream, the water quality of the Potomac River deteriorated. This created conditions of severe eutrophication. It is said that President Abraham Lincoln used to escape to the highlands on summer nights to escape the river's stench. In the 1960s, with dense green algal blooms covering the river's surface, President Lyndon Johnson declared the river "a national disgrace" and set in motion a long-term effort to reduce pollution from sewage and restore the beauty and ecology of this historic river. One of the significant pollution control projects at the time was the expansion of the Blue Plains Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant, which serves Washington and several surrounding communities.[37] Enactment of the 1972 Clean Water Act led to construction or expansion of additional sewage treatment plants in the Potomac watershed. Controls on phosphorus, one of the principal contributors to eutrophication, were implemented in the 1980s, through sewage plant upgrades and restrictions on phosphorus in detergents.[36]

By the end of the 20th century, notable success had been achieved, as massive algal blooms vanished and recreational fishing and boating rebounded. Still, the aquatic habitat of the Potomac River and its tributaries remain vulnerable to eutrophication, heavy metals, pesticides and other toxic chemicals, over-fishing, alien species, and pathogens associated with fecal coliform bacteria and shellfish diseases. In 2005 two federal agencies, the US Geological Survey and the Fish and Wildlife Service, began to identify fish in the Potomac and tributaries that exhibited "intersex" characteristics, as a result of endocrine disruption caused by some form of pollution.[38]

On November 13, 2007, the Potomac Conservancy, an environmental group, issued the river a grade of "D-plus", citing high levels of pollution and the reports of "intersex" fish.[39] Since then, the river has improved with a reduction in nutrient runoff, return of fish populations, and land protection along the river. As a result, the same group issued a grade of "B" for 2017 and 2018.[40] In March 2019, the Potomac Riverkeeper Network launched a laboratory boat dubbed the "Sea Dog", which will be monitoring water quality in the Potomac and providing reports to the public on a weekly basis;[41] in that same month, the catching near Fletcher's Boat House of a Striped Bass estimated to weigh 35 lb (16 kg) was seen as a further indicator of the continuing improvement in the health of the river.[42]

| Top Ten Historic Crests of the Potomac River, 1877–2017 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kitzmiller | Hancock | Williamsport | Shepherdstown | ||||

| Harpers Ferry | Point of Rocks | Little Falls | Georgetown | ||||

| Source: National Weather Service | |||||||

Discharge

The average daily flow during the water years 1931–2018 was 11,498 cubic feet (325.6 m3) /s.[2] The highest average daily flow ever recorded on the Potomac at Little Falls, Maryland (near Washington, D.C.), was in March 1936 when it reached 426,000 cubic feet (12,100 m3) /s.[2] The lowest average daily flow ever recorded at the same location was 601.0 cubic feet (17.02 m3) /s in September 1966[2] The highest crest of the Potomac ever registered at Little Falls was 28.10 ft, on March 19, 1936;[43][28] however, the most damaging flood to affect Washington, DC and its metropolitan area was that of October 1942.[44]

Legal issues

For 400 years Maryland and Virginia have disputed control of the Potomac and its North Branch since both states' original colonial charters grant the entire river rather than half of it as is normally the case with boundary rivers. In its first state constitution adopted in 1776, Virginia ceded its claim to the entire river but reserved free use of it, an act disputed by Maryland. Both states acceded to the 1785 Mount Vernon Compact and the 1877 Black-Jenkins Award which granted Maryland the river bank-to-bank from the low-water mark on the Virginia side while permitting Virginia full riparian rights short of obstructing navigation.

From 1957 to 1996, the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) routinely issued permits applied for by Virginia entities concerning the use of the Potomac. However, in 1996 the MDE denied a permit submitted by the Fairfax County Water Authority to build a water intake 725 feet (220 m) offshore, citing potential harm to Maryland's interests by an increase in Virginia sprawl caused by the project. After years of failed appeals within the Maryland government's appeal processes, in 2000 Virginia took the case to the Supreme Court of the United States, which exercises original jurisdiction in cases between two states. Maryland claimed Virginia lost its riparian rights by acquiescing to MDE's permit process for 63 years (MDE began its permit process in 1933). A Special Master appointed by the Supreme Court to investigate recommended the case be settled in favor of Virginia, citing the language in the 1785 Compact and the 1877 Award. On December 9, 2003, the Court agreed in a 7–2 decision.[45]

The original charters are silent as to which branch from the upper Potomac serves as the boundary, but this was settled by the 1785 Compact. When West Virginia seceded from Virginia in 1863, the question of West Virginia's succession in title to the lands between the branches of the river was raised, as well as title to the river itself. Claims by Maryland to West Virginia land north of the South Branch (all of Mineral and Grant Counties and parts of Hampshire, Hardy, Tucker and Pendleton Counties) and by West Virginia to the Potomac's high-water mark were rejected by the Supreme Court in two separate decisions in 1910.[46][47]

Fauna

Fish

A variety of fish inhabit the Potomac, including bass, muskellunge, pike, walleye. The northern snakehead, an invasive species resembling the native bowfin, lamprey, and American eel, was first seen in 2004.[48][49] Many species of sunfish are also present in the Potomac and its headwaters.[50] Although rare, bull sharks can be found.[51]

After having been depressed for many decades, the river's population of American shad is currently re-bounding as a result of the ICPRB's successful "American Shad Restoration Project" that was begun in 1995. In addition to stocking the river with more than 22 million shad fry, the Project supervised the construction of a fishway that was built to facilitate the passage of adults around the Little Falls Dam on the way to their traditional spawning grounds upstream.[52]

| Freshwater fish of the Potomac River |

|---|

*denotes naturalized species; Sources: |

| Tidal freshwater fish of the Potomac River |

|---|

Sources: |

Mammals

| Mammals of the Potomac River Basin |

|---|

*denotes introduced species Sources:

|

Early European colonists who settled along the Potomac found a diversity of large and small mammals living in the dense forests nearby. Bison, elk, wolves (both gray and red) and cougars were still present at that time, but had been hunted to extirpation by the middle of the 19th century. Among the denizens of the Potomac's banks, beavers and otters met a similar fate, while small populations of American mink and American martens survived into the 20th century in some secluded areas.

There is no record of early settlers having observed marine mammals in the Potomac, but several sightings of Atlantic bottle-nosed dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) were reported during the 19th century. In July 1844, a pod of 14 adults and young was followed up the river by men in boats as high as the Aqueduct Bridge (approximately the same location occupied by Key Bridge today).[53]

Since 2015, perhaps as a result of warmer temperatures, rising water levels in the Chesapeake Bay and improving water quality in the Potomac, unprecedented numbers of Atlantic bottle-nosed dolphins have been observed in the river. According to Dr. Janet Mann of Georgetown University's Potomac-Chesapeake Dolphin Project, more than 500 individual members of the species have been identified in the Potomac during this period.[54]

Birds

| Birds of the Potomac River Basin |

|---|

Reptiles

| Turtles of the Potomac River Basin |

|---|

*denotes naturalized species Sources: |

| Snakes of the Potomac River basin |

|---|

Sources: |

| Lizards of the Potomac River Basin |

|---|

Sources: |

Amphibians

| Salamanders of the Potomac River Basin |

|---|

Sources: |

| Frogs and toads of the Potomac River Basin |

|---|

*denotes naturalized species Sources: |

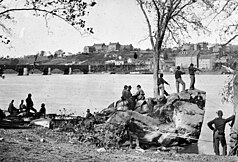

Additional images

Upper and lower Potomac

|

Tidal Potomac

|

Other

|

See also

- Air Florida Flight 90, a flight crashed into Potomac River just after takeoff from Washington National Airport

- List of cities and towns along the Potomac River

- List of crossings of the Potomac River

- List of islands on the Potomac River

- List of rivers of Maryland

- List of rivers of Virginia

- List of rivers of West Virginia

- List of tributaries of the Potomac River

- List of variant names of the Potomac River

- Potomac Heritage Trail

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ AQU: The diversion dam at Great Falls, often called the "Aqueduct Dam", was built in the 1850s by the US Army Corps of Engineers as part of the project assigned to them by Congress to supply clean water from above Great Falls to Washington, DC. Water diverted by the dam flows 12 miles through a 9-foot diameter pipeline to Dalecarlia Reservoir on the outskirts of the city where it is first allowed to settle and then filtered and purified before being distributed to consumers. Since 1927, potable water from Dalecarlia has also been provided to Arlington County and some other sections of nearby northern Virginia through three 20-inch diameter pipelines that cross the Potomac under the deck of Chain Bridge. In addition, there is nearby a 4-foot diameter conduit constructed in 1967 that traverses the Potomac beneath the riverbed which is used primarily for backup purposes.[55][56]

- ^ GHL: "Evidence of the ancient Potomac River bed can be seen in well-rounded boulders, smoothed surfaces and grooves, and beautifully formed potholes. Look for sandstone boulders along the trail, which were deposited by massive floods. The sandy soils along the river trail, with shells mixed in, are a result of sediment deposits from floods. Some of the oldest sediment deposits in the area can be found on Glade Hill, between the Matildaville and Carriage Road trails. Glade Hill was once an island in the Potomac River, and the deposits found there were left before Mather Gorge formed."[57]

- ^ PIF: "In the Late Pennsylvanian, the rocks of the Stubblefield Falls domain of the Mather Gorge Formation moved up relative to the Sykesville Formation on the steep, west-dipping Plummers Island fault and mylonite zones (Schoenborn, 2001) within an existing Plummers Island shear zone (figs. 5, 6). Shearing formed S2 cleavage with below-closure muscovite growth and more pervasive S2 cleavage in the Sykesville Formation. By the earliest Permian, all of the rocks in the Potomac terrane had cooled through 235°C (figs. 3, 5). Apatite fission-track data indicate cooling through ~90°C to 100°C in Early Jurassic to Early Cretaceous time, with increasing ages to the east, suggesting kilometer-scale rotation of the Potomac terrane in the Cretaceous and (or) Tertiary, with the west side up."[58]

- ^ BLK: "Two samples collected from the terrace dissected by Great Falls indicate that the Falls were established in their current location by 30 ky. A series of 6 samples taken from a vertical transect just below the falls, indicates that vertical incision continued a rate of 0.5 m/ky between 27 and 12 ky, increasing to nearly 1.0 m/ky during the Holocene. These data suggest that the drop over Great Falls is growing with time. A dramatic increase in outcrop weathering and soil depth 3.5 km downstream of the Falls, suggests that prior to establishment of the Great Falls knickzone, a similar feature was likely present near Black Pond. 10-Be data are not yet available for this paleo knick zone; however, a 10-Be model age >200 ky from the top of Plummers island 5 km down stream of Black Pond suggests a much older period of retreat led to the formation of the Black Pond paleo knick zone."[59]

- ^ PES: "The Potomac Estuary: From the Chain Bridge in Washington, DC, to Point Lookout at the confluence with the Chesapeake Bay, the Potomac Estuary is a long and narrow estuary—approximately 189 km. With its many tributaries and bays, however, the Potomac Estuary has a shoreline of 1,800 km. The Estuary meanders in a south, southeasterly direction, except for a sharp bend about halfway downriver. The Estuary has three well-defined and distinct zones. The upper zone, from Chain Bridge to Indian Head, is the tidal freshwater reach, with salinities of less than 0.5 parts per thousand (ppt). The middle reach, between Indian Head and the Route 301 Bridge at Morgantown, is the transition zone. The salinity of this zone varies from 0.5 to 7.0 ppt and is often referred to as the zone of maximum turbidity. The lower zone, from the 301 Bridge to Point Lookout, has salinities ranging from 7 to 16 ppt."[60]

- ^ TRI: The rocky western (upriver) and central portions of the island are part of the Piedmont Plateau, while the southeastern part is within the Atlantic Coastal Plain. At one point opposite Georgetown, the Atlantic Seaboard fall line between the Piedmont and the Coastal Plain can be seen as a natural phenomenon. The island has about 2.5-mile (4.0 km) of shoreline, and the highest area of the island (where the Mason mansion stood) is about 44 feet (13 m) above sea level.

References

- ^ "President Clinton: Celebrating America's Rivers". American Heritage Rivers. July 30, 1998. Archived from the original on April 28, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "USGS 01646500 POTOMAC RIVER NEAR WASH, DC LITTLE FALLS PUMP STA". nwis.waterdata.usgs.gov. National Weather Service (NOAA). 2019. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "(Arakawa - Potomac sister rivers)". Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin. January 27, 2012. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived March 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 15, 2011

- ^ a b "Facts & FAQs". Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin (ICPRB), Rockville, MD. September 16, 2009. Archived from the original on January 15, 2010. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ "POTOMAC BASIN FACTS". Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ "Potomac River Water Trail". NRT Database. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ "Designation of Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary". www.federalregister.gov. September 9, 2019.

- ^ a b "Geology of Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail". Potomac Heritage. NPS. 2019. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ "Potomac Riverkeeper Network". www.potomacriverkeepernetwork.org. Potomac Riverkeeper Network. 2019. Archived from the original on November 19, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ "Potomac River Basin Fact Sheet" (PDF). www.potomacriver.org. Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin (ICPRB). October 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ Reed, John Calvin. "The River and the Rocks: The Geologic Story of Great Falls and the Potomac River Gorge" (PDF). pubs.usgs.gov. USGS. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016.

- ^ Legends of Loudoun: An account of the history and homes of a border county of Virginia's Northern Neck, Harrison Williams, p. 26.

- ^ a b Achenbach, Joel (2004). The Grand Idea: George Washington's Potomac and the Race to the West. Simon and Schuster. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-684-84857-0.

- ^ Hagemann, James A. (1988). The Heritage of Virginia. The Donning Company, 2nd edition, 297 p. ISBN 0-89865-255-3.

- ^ "Potomac River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "Chesapeake Swan Song exhibition opens April 11 at CBMM". Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. January 26, 2015. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas (1814). The Proceedings of the Government of the United States, in Maintaining the Public Right to the Beach of the Missisipi: Adjacent to New-Orleans, Against the Intrusion of Edward Livingston. Edward J. Coale. pp. 200–. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

I have heard of an etymologist who derived the name of the river Potomac from the Greek Potamos. This derivation is quite as probable as that of beach from beotian; being founded on a much greater similarity of sound, as well as analogy of sense.

- ^ Campbell, Douglas E.; Sherman, Thomas B. (July 25, 2014). On the Potomac River. Lulu.com. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-1-304-69872-8. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ Sorenson, John L.; Raish, Martin (1996). Pre-Columbian Contact with the Americas Across the Oceans: An Annotated Bibliography. Research Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-934893-23-7. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ Bugbee, Mary F. "The Early Planning of Sites for Federal and Local Use in Washington, D. C." Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., vol. 51/52, 1951, p. 19. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40067294. Retrieved 19 Feb. 2024.

- ^ Peck, Garrett (2012). The Potomac River: A History and Guide. Charleston, SC: The History Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-60949-600-5.

- ^ Hahn, Thomas (1984). The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal: Pathway to the Nation's Capital. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-1732-2.

- ^ Ways, Harry C. (1996). The Washington Aqueduct: 1852-1992. (Baltimore, MD: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District)

- ^ Washington Aqueduct

- ^ "The 10 Most Populous Metro Areas : July 1, 2015" (PDF). www.census.gov. US Census Bureau. July 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ a b "1936 Flood Retrospective: The Flood of March 17-19 1936". weather.gov. NWS. March 16, 2016. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Carey, Frank (December 4, 1963). "Potomac Dam Is Opposed By Virginians". Fredericksburg Free-Lance Star. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ Grey, Karen (March 2018). "Canal Engineering from Dam 3 to Harpers Ferry" (PDF). candocanal.org. 'Along the Towpath', C&O Canal Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 22, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ Holdsworth, Bill (April 2013). "Level 51 (Dam #6)". candocanal.org. C&O Canal Association. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ Unrau, Harland D. (August 2007). "Historical Resource Study: Chesapeake & Ohio Canal" (PDF). US Department of the Interior, National Park Service. pp. 208, 470. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ Joel Achenbach (May 5, 2002). "America's River". The Washington Post. pp. W12. Archived from the original on September 16, 2002.

- ^ "Jennings Randolph Lake, MD & WV" (PDF). www.nab.usace.army.mil. USACE (United States Corps of Engineers). February 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- ^ Scott, Pamela (2007), "Capital Engineers: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the Development of Washington, D.C., 1790–2004." Archived February 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.) Publication No. EP 870-1-67. p. 256.

- ^ a b ICPRB. "Potomac Timeline." Archived January 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Updated 2008-04-15.

- ^ District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority. Washington, DC. "History of Blue Plains Wastewater Treatment Plant." Archived March 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010-09-28.

- ^ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Annapolis, MD (2009). "Intersex fish: Endocrine disruption in smallmouth bass." Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fahrenthold, David A. (November 13, 2007). "Potomac Recovery Deemed At Risk". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 1, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ^ "Potomac Report Card". Potomac Conservancy. March 28, 2018. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Lang, Marissa J. "Taking a swim in the Potomac? Weekly readings will reveal water quality and bacteria levels" Archived September 8, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2019-03-30.

- ^ "Need a bigger boat: 35-pound bass caught on the Potomac River" Archived April 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Washington Post. 2019-04-03. Accessed: 2019-04-03.

- ^ "Historic Crests for Potomac near Washington, DC (Little Falls)". National Weather Service - Water. 2019. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ Little, Becky (September 14, 2018). "World War II-Era Flood Was the Worst in D.C.'s History". HISTORY. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ U.S. Supreme Court. Virginia v. Maryland, 540 U.S. 56 (2003)

- ^ Maryland v. West Virginia, 217 U.S. 1 (1910)

- ^ Maryland v. West Virginia, 217 U.S. 577 (1910)

- ^ Potomac snakeheads not related to others Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Associated Press, Baltimore Sun, April 27, 2007.

- ^ "Northern Snakehead". Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Jim Cummins (2013). "Fishes of the freshwater potomac" (PDF). www.potomacriver.org. Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ "Sharks! Watermen catch two 8-footers on same day". somdnews.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ "THE POTOMAC RIVER AMERICAN SHAD RESTORATION PROJECT" (PDF). www.potomacriver.org. Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin. March 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ "The Mysterious Dolphins of the Potomac". 2017. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ "Potomac-Chesapeake Dolphin Project". 2018. Archived from the original on April 6, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ "Water, Water ... " by Larry Van Dyne, Washingtonian Magazine (March 2007)

- ^ "Sources of Northern Virginia Drinking Water", Virginia Places

- ^ Great Falls Geology Archived January 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, National Park Service, April 10, 2015

- ^ Michael J. Kunk, et al., Multiple Paleozoic Metamorphic Histories, Fabrics, and Faulting in the Westminster and Potomac Terranes, Central Appalachian Piedmont, Northern Virginia and Southern Maryland Archived December 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Geological Survey, 23 November 2016

- ^ Paul Bierman, et al., Great Falls is 30,000 Years Old Archived September 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Paper No. 35-5, Session No. 35, Geomorphic Process Rates on the Passive Margin, March 26, 2004. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, Vol. 36, No. 2, p. 94

- ^ "Chapter One: Introduction" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

Works cited

- Rice, James D., Nature and History in the Potomac Country: From Hunter-Gatherers to the Age of Jefferson. (2009), Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; ISBN 0-8018-9032-2; ISBN 978-0-8018-9032-1

- Smith, J. Lawrence, The Potomac Naturalist: The Natural History of the Headwaters of the Historic Potomac (1968), Parsons, WV: McClain Printing Co.; ISBN 0-87012-023-9; ISBN 978-0-87012-023-7

External links

- Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service - Baltimore/Washington (Sterling, VA) - including Potomac River levels

- Potomac River level at Williamsport

- Potomac River level at Harpers Ferry

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Pages using the Phonos extension

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with short description

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Use mdy dates from March 2019

- Articles with text in Algonquian languages

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages including recorded pronunciations

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2024

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Pages using Sister project links with default search

- Potomac River

- Potomac River watershed

- Rivers of Washington, D.C.

- Rivers of Maryland

- Rivers of Virginia

- Rivers of West Virginia

- Monongahela National Forest

- History of West Virginia

- Borders of Maryland

- Borders of Virginia

- Borders of West Virginia

- American Heritage Rivers

- Tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay

- West Virginia placenames of Native American origin

- National Recreation Trails in Washington, D.C.

- National Recreation Trails in Maryland

- National Recreation Trails in Virginia

- National Recreation Trails in West Virginia

- Pages using the Kartographer extension