Monarchy in Nova Scotia

| King in Right of Nova Scotia | |

|---|---|

Provincial | |

| |

| Incumbent | |

| |

| Charles III King of Canada since 8 September 2022 | |

| Details | |

| Style | His Majesty |

| First monarch | Victoria |

| Formation | 1 July 1867 |

By the arrangements of the Canadian federation, the Canadian monarchy operates in Nova Scotia as the core of the province's Westminster-style parliamentary democracy.[1] As such, the Crown within Nova Scotia's jurisdiction is referred to as the Crown in Right of Nova Scotia,[2] His Majesty in Right of Nova Scotia,[3] or the King in Right of Nova Scotia.[4] The Constitution Act, 1867, however, leaves many royal duties in the province specifically assigned to the sovereign's viceroy, the lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia,[1] whose direct participation in governance is limited by the conventional stipulations of constitutional monarchy.[5]

Constitutional role

The role of the Crown is both legal and practical; it functions in Nova Scotia in the same way it does in all of Canada's other provinces, being the centre of a constitutional construct in which the institutions of government acting under the sovereign's authority share the power of the whole.[6] It is thus the foundation of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the province's political system.[7] The Canadian monarch—since 8 September 2022, King Charles III—is represented and his duties carried out by the lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia, whose direct participation in governance is limited by the conventional stipulations of constitutional monarchy, with most related powers entrusted for exercise by the elected parliamentarians, the ministers of the Crown generally drawn from among them, and the judges and justices of the peace.[5] The Crown today primarily functions as a guarantor of continuous and stable governance and a nonpartisan safeguard against the abuse of power.[10]

This arrangement began with the 1867 British North America Act and continued an unbroken line of monarchical government extending back to the late 16th century.[1] However, though it has a separate government headed by the King, as a province, Nova Scotia is not itself a kingdom.[11]

Aside from meetings with the first minister and other ministers of the Crown for affairs of state, the lieutenant governor annually hosts a meeting of the full cabinet at Government House, "thereby bringing the main actors in our system of responsible government to the place where our system of democracy was first practiced." The viceroy also holds regular audiences with the clerk of the Executive Council to review state papers.[12]

Government House in Halifax is owned by the sovereign in his capacity as King in right of Nova Scotia and is used as an official residence by the lieutenant governor, and the sovereign when in Nova Scotia.[citation needed]

Royal associations

Those in the royal family perform ceremonial duties when on a tour of the province; the royal persons do not receive any personal income for their service, only the costs associated with the exercise of these obligations are funded by both the Canadian and Nova Scotia Crowns in their respective councils.[13] Monuments around Nova Scotia mark some of those visits, while others honour a royal personage or event. Further, Nova Scotia's monarchical status is illustrated by royal names applied regions, communities, schools, and buildings, many of which may also have a specific history with a member or members of the royal family. Associations also exist between the Crown and many private organizations within the province; these may have been founded by a royal charter, received a royal prefix, and/or been honoured with the patronage of a member of the royal family. Examples include the Royal Nova Scotia International Tattoo, which was under the patronage of Queen Elizabeth II and received its royal prefix from her in 2006.

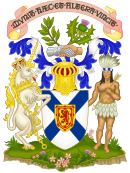

The main symbol of the monarchy is the sovereign himself, his image (in portrait or effigy) thus being used to signify government authority.[14] A royal cypher or crown may also illustrate the monarchy as the locus of authority, without referring to any specific monarch. Further, though the monarch does not form a part of the constitutions of Nova Scotia's honours, they do stem from the Crown as the fount of honour and, so, bear on the insignia symbols of the sovereign.

History

The first colonies

The roots of the present Crown in Nova Scotia lie in Jacques Cartier's claim, in 1534, of Chaleur Bay for King Francis I; though, the area was not officially settled until King Henry IV established a colony there in 1604, administered by the governor of Acadia in the capital of Port-Royal, so named for the King. Only slightly later, King James VI and I laid claim to areas overlapping with Acadia, in what is today Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and part of Maine, and brought it within the Scottish Crown's dominion, calling the region Nova Scotia (or "new Scotland").[15][16] James' son, Charles I, issued the Charter of New Scotland, which created the baronets of Nova Scotia, many of which continue to exist today.

Over the course of the 17th century, the French Crown lost, via war and treaties, its Maritimes territories to the British sovereign, Acadia being gradually taken until it fully became British territory through the Treaty of Paris in 1763 and the name Nova Scotia was applied to the whole region. But, this placement of French people under a British sovereign did not transpire without problems; French colonialists in Acadia were asked by British officials, uneasy about where the Acadians' loyalties lay, to reaffirm their allegiance to King George III. The Acadians refused, not as any slight to the King, but, more to remain Catholic, and were subsequently deported from the area in what became known as the Great Upheaval.

The arrival of United Empire Loyalists

During and following the American Revolution, some 35,000 to 40,000 United Empire Loyalists, as well as about 3,500 Black Loyalists, fled from the Thirteen Colonies and then the United States to Nova Scotia, refugees from the violence directed against them during the war.[17] So many arrived that New Brunswick was split out of Nova Scotia as a separate colony.

Not all who settled in the colony were immediately made to feel comfortable, however, as many of the already resident families were aligned with the United States and its republican cause; Colonel Thomas Dundas wrote from Saint John in 1786, "[the Loyalists] have experienced every possible injury from the old inhabitants of Nova Scotia, who are even more disaffected towards the British government than any of the new states ever were. This makes me much doubt their remaining long dependent."[18]

Prince William Henry (later King William IV) arrived at the Royal Naval Dockyards in Halifax in late 1786,[19] on board his frigate, HMS Pegasus. Although he received a royal reception, it was later made clear the Prince would be granted no further special treatment other than already accorded to an officer of his rank in the Royal Navy. Of Halifax, the Prince said, "a very gay and lively place full of women and those of the most obliging kind." It was in this period of William's life that he began his own long history of inappropriate liaisons.[19] Further, although he was strict about rules and protocol, himself, he was also known to occasionally break them and, as punishment for taking his ship from the Caribbean back to Halifax without orders to do so, he was commanded to spend the winter of 1787 to 1788 at Quebec City. Instead, William disobeyed again and sailed to Britain, infuriating the admiralty and the King. The Prince was forced to remain in the harbour at Portsmouth to await return to Halifax the next year. That return became all the more urgent when it was discovered William had begun an affair in Portsmouth, prompting the King to say, "what? William playing the fool again? Send him off to America and forbid the return of the ship to Plymouth."[20]

Prince William Henry returned to Nova Scotia in July 1788, this time aboard HMS Andromeda, and remained there for another year.[20] Back in the United Kingdom, he met Dorothea Jordan, a woman he could not legally marry, but, nonetheless, with whom William carried on a decades-long relationship, fathering, with her, 10 children, all of which bore the name FitzClarence, meaning "son of Clarence", stemming from William's title, Duke of Clarence. Two of the Prince's illegitimate daughters lived in Halifax, one, Mary, in 1830 and the other, Amelia, from 1840 to 1846, while her husband, the Viscount Falkland, served as Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia.[21] Upon his accession as King William IV in 1830, he sent a portrait of himself to the Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia, recalling his earlier life in the colonial capital.[20]

The residence of Prince Edward

A son of King George III, Prince Edward, was sent in 1794 to take command of Nova Scotia. While he travelled extensively around the colony,[22] he lived in Halifax, based at the headquarters of the Royal Navy's North American Station; though, Lieutenant Governor Sir John Wentworth and Lady Francis Wentworth provided their country residence for the use of Edward and his French-Canadian mistress, Julie St. Laurent, where they hosted various dignitaries, including Louis-Phillippe of Orléans (the future Louis Philippe I, King of the French). The Prince extensively renovated the estate, including designing and overseeing the construction of Prince's Lodge (or the Music Room). He also oversaw the reconstruction of Fort George[23] and the officer's quarters at Fort Anne[22] and designed and had built the Halifax Town Clock and St George's Church (also known as the Round Church).[n 1] The King and Edward's brother, Prince Frederick, were highly supportive of the latter project, the King providing a £200 donation.[26] Additionally, Edward prompted the construction of numerous roads, made improvements to the Grand Parade,[27] and devised a semapore telegraph system between Halifax and Fredericton, New Brunswick.[28]

After falling from his horse in late 1798, the Prince returned to the United Kingdom, where his father created him Duke of Kent and Strathearn and appointed Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America.[29] He voyaged back to Nova Scotia in mid-1799 and remained there for another year, before sailing back, once more, to Britain.

War and peace

In the War of 1812, the United States endeavoured to conquer the Canadas;[35] all the American parties involved assumed their troops would be greeted as liberators.[36] During the conflict, Alexander Cochrane, the Commander-in-Chief, North American Station, issued a proclamation on 2 April 1814, which stated:

Whereas it has been represented to me that many persons now resident in the United States have expressed a desire to withdraw therefrom with a view to entering into His Majesty's service, or of being received as free settlers into some of His Majesty's colonies. This is therefore to give notice that all persons who may be disposed to migrate from the United States, will, with their families, be received on board of His Majesty's ships or vessels of war, or at the military posts that may be established upon or near the coast of the United States, when they will have their choice of either entering into His Majesty's sea or land forces, or of being sent as free settlers to the British possessions in North America or the West Indies, where they will meet with due encouragement.[37]

In total, about 4,000 escaped slaves and their families,[38] known as the Black Refugees, were transported out of the United States by the Royal Navy during and after the war.[39][38] About half settled in Nova Scotia and approximately 400 in New Brunswick.[40]

Samuel Cunard, a born-Haligonian, led a group of Halifax investors to combine with a Quebec business in 1831 to build the pioneering ocean steamship, the SS Royal William, named for the new king, William IV, and built at Cap-Blanc, Lower Canada.[41] It was launched on 27 April 1831, by Louisa, the Lady Alymer, wife of the Governor General of British North America, the Lord Aylmer, and was the largest passenger ship in the world at the time and became the first to cross the Atlantic Ocean almost entirely by steam power.[42] Cunard went on to found the Cunard Line, starting with the RMS Britannia, and the company would eventually launch the RMS Queen Mary (1936), RMS Queen Elizabeth (1940), Queen Elizabeth 2 (1969), RMS Queen Mary 2 (2004), MS Queen Victoria (2007), MS Queen Elizabeth (2010), and MS Queen Anne (2024).

Queen Victoria's eldest son and heir, Prince Albert Edward (later King Edward VII) for four months toured the Maritimes and Province of Canada in 1860.[43] Arriving at Halifax from St. John's, Newfoundland, on 2 August, he visited the various buildings his grandfather designed and/or had erected, including Prince Edward's country home, Prince's Lodge.[44] The Prince undertook a fishing trip and camped overnight at Boutilier farm, near Bowser Station.[45] From the colonial capital, the royal party travelled by train to Windsor and Hantsport, where they boarded HMS Styx to cross the Bay of Fundy to Saint John, New Brunswick.[46] After touring New Brunswick, the Prince returned to Nova Scotia, arriving at Pictou to board HMS Hero and return to several communities, including Saint John and Windsor.[46]

Albert Edward was followed by his younger brother, Prince Alfred, who embarked on a five week tour of the same areas in 1861.[47] The Prince visited the Tangier gold mines in Nova Scotia,[48][49] Prince Alfred Arch, marking where Alfred stepped ashore on 19 October, still standing in the town today.[50]

The 20th century

For the bicentennial in 1983 of the arrival of the first Empire Loyalists in Nova Scotia, Charles, Prince of Wales, and his wife, Diana, Princess of Wales, attended the celebrations.[51]

In 2022, Nova Scotia instituted a provincial Platinum Jubilee medal to mark the Elizabeth II's seventy years on the Canadian throne; the first time in Canada's history that a royal occasion was commemorated on provincial medals.[52]

To merk the 175th anniversary of responsible government in the province, King Charles III sent a message on 2 February 2023, noting that, during his tour of Nova Scotia in 2014, he was sworn into the Queen's Privy Council for Canada in the same room at Government House in Halifax where Lieutenant Governor John Harvey swore in the first democratically accountable cabinet in Canada's history. The King stated, "at that time, I was struck by the historic setting and its profound significance in the history of Canada and the Commonwealth."[53]

See also

Notes

- ^ In a retrospective article published on the death of Fleiger's daughter in 1890, she is reported to have recalled events that occurred during the life of the Duke of Kent who, she noted, "had a great love of architecture peculiar in form and Mr Fleiger, at his request, designed the plan, or rough sketch, for the Round Church."[24] The Round Church was a reference to St George's Anglican Church in Halifax.[25]

References

- ^ a b c Victoria (29 March 1867), Constitution Act, 1867, III.9, V.58, Westminster: Queen's Printer, retrieved 15 January 2009

- ^ Transport Canada (1994), Transport Canada > Safety > Transportation of Dangerous Goods > TDG Act & Regulations > Agreements Respecting Administration of the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act, 1992 > Nova Scotia, Queen's Printer for Canada, retrieved 9 July 2009

- ^ Transport Canada 1994, 18.a

- ^ Elizabeth II (2005), Municipal Funding Agreement (PDF), Halifax: Queen's Printer for Nova Scotia, archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2006, retrieved 9 July 2009

- ^ a b c MacLeod, Kevin S. (2008). A Crown of Maples (PDF) (1 ed.). Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-662-46012-1. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ Cox, Noel (September 2002). "Black v Chrétien: Suing a Minister of the Crown for Abuse of Power, Misfeasance in Public Office and Negligence". Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law. 9 (3). Perth: Murdoch University: 12. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ Privy Council Office (2008), Accountable Government: A Guide for Ministers and Ministers of State – 2008, Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada, p. 49, ISBN 978-1-100-11096-7, archived from the original on 18 March 2010, retrieved 17 May 2009

- ^ Roberts, Edward (2009). "Ensuring Constitutional Wisdom During Unconventional Times" (PDF). Canadian Parliamentary Review. 23 (1). Ottawa: Commonwealth Parliamentary Association: 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ^ MacLeod 2008, p. 20

- ^ [5][8][9]

- ^ Forsey, Eugene (31 December 1974), "Crown and Cabinet", in Forsey, Eugene (ed.), Freedom and Order: Collected Essays, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd., ISBN 978-0-7710-9773-7

- ^ 175th Anniversary of Responsible Government in Nova Scotia, King's Printer for Nova Scotia, 2 February 2023, retrieved 4 June 2023

- ^ Palmer, Sean; Aimers, John (2002), The Cost of Canada's Constitutional Monarchy: $1.10 per Canadian (2 ed.), Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada, archived from the original on 19 June 2008, retrieved 15 May 2009

- ^ MacKinnon, Frank (1976), The Crown in Canada, Calgary: Glenbow-Alberta Institute, p. 69, ISBN 978-0-7712-1016-7

- ^ Bousfield, Arthur; Toffoli, Garry, Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada, Canadian Royal Heritage Trust, archived from the original on 18 June 2009, retrieved 10 July 2009

- ^ Fraser, Alistair B. (30 January 1998), "XVII: Nova Scotia", The Flags of Canada, University Park, retrieved 10 July 2009

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Censuses of Canada 1665 to 1871: Upper Canada & Loyalists (1785 to 1797), Statistics Canada, 22 October 2008, retrieved 24 July 2013

- ^ Clark, S.D. (1978), Movements of Political Protest in Canada, 1640–1840, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 150–151

- ^ a b Bousfield, Arthur; Toffoli, Garry (2010). Royal Tours 1786-2010: Home to Canada. Dundurn Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-4597-1165-5.

- ^ a b c Bousfield & Toffoli 2010, p. 28

- ^ Bousfield & Toffoli 2010, p. 29

- ^ a b Tidridge, Nathan, Prince Edward and Nova Scotia, the Crown in Canada, retrieved 4 April 2023

- ^ "Halifax Citadel National Historic Site of Canada". Parks Canada. 19 September 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "Unknown", Morning Herald, 1 (7 ed.), Halifax, 1 February 1890

- ^ Rosinski, M. (1994), Architects of Nova Scotia: A Biographical Dictionary, p. 39

- ^ "Fleiger, John Henry", Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800-1950, Drupal, retrieved 17 February 2023

- ^ Department of Canadian Heritage, Ceremonial and Canadian Symbols Promotion > The Canadian Monarchy > 2005 Royal Visit > The Royal Presence in Canada - A Historical Overview, Queen's Printer for Canada, archived from the original on 7 August 2007, retrieved 4 November 2007

- ^ Tidridge, Nathan, Prince Edward and New Brunswick, the Crown in Canada, retrieved 4 April 2023

- ^ Longford, Elizabeth (2004). "Edward, Prince, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (1767–1820)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8526. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Heidler, David S.; Heidler, Jeanne T. (2002). The War of 1812. Westport; London: Greenwood Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-313-31687-2.

- ^ Pratt, Julius W. (1925). Expansionists of 1812. New York: Macmillan. pp. 9–15.

- ^ Hacker, Louis M. (March 1924). "Western Land Hunger and the War of 1812: A Conjecture". Mississippi Valley Historical Review. X (4): 365–395. doi:10.2307/1892931. JSTOR 1892931.

- ^ Hickey, Donald R. (1989). The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. Urbana; Chicago: University of Illinois Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-252-01613-0.

- ^ Carlisle, Rodney P.; Golson, J. Geoffrey (1 February 2007). Manifest Destiny and the Expansion of America. ABC-CLIO. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-85109-833-0.

- ^ [30][31][32][33][34]

- ^ Hickey, Donald R. (2012). The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict, Bicentennial Edition. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-252-07837-8.

- ^ ADM 1/508 folio 579.

- ^ a b "Black Sailors and Soldiers in the War of 1812", War of 1812, PBS, 2012, archived from the original on 24 June 2020, retrieved 1 October 2014

- ^ Bermingham, Andrew P. (2003), Bermuda Military Rarities, Bermuda Historical Society; Bermuda National Trust, ISBN 978-0-9697893-2-1

- ^ Whitfield, Harvey Amani (2006), Blacks on the Border: The Black Refugees in British North America, 1815–186, University of Vermont Press, p. 34, ISBN 978-1-58465-606-7

- ^ Blakeley, Phyllis R. (1976). "Cunard, Sir Samuel". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IX (1861–1870) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Bousfield & Toffoli 2010, p. 29

- ^ Bentley-Cranch, Dana (1992), Edward VII: Image of an Era 1841–1910, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, pp. 20–34, ISBN 978-0-11-290508-0

- ^ Bousfield & Toffoli 2010, p. 45

- ^ Brown, Thomas J. (1922), Nova Scotia Place Names (PDF), p. 22, retrieved 13 August 2023

- ^ a b Bousfield & Toffoli 2010, p. 46

- ^ "Prince Alfred's Tour in the Canadas", Montreal Gazette, 6 July 1861, retrieved 19 February 2023

- ^ Men in the Mines > A History of Mining Activity in Nova Scotia, 1720-1992 > HRH Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, Nova Scotia Archives, 20 April 2020, retrieved 19 February 2023

- ^ Prince Alfred Arch / L'Arche Prince Alfred, The Historical Marker Database, retrieved 2 April 2023

- ^ "Tangier", Not Your Grandfather's Mining Industry, Mining Association of Nova Scotia, retrieved 19 February 2023

- ^ Royal Visits to Canada, CBC, retrieved 10 July 2009

- ^ "Commemorative Medal Created for Queen's Platinum Jubilee". novascotia.ca. 30 March 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Davison, Janet (February 12, 2023), The royals have their causes, but how much difference can they make?, CBC News, retrieved June 4, 2023

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Wikipedia articles incorporating a citation from the ODNB

- Pages using cite ODNB with id parameter

- CS1: long volume value

- Articles with short description

- Short description matches Wikidata

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2024

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Monarchy of Canada