Moctezuma II

| Moctezuma II | |

|---|---|

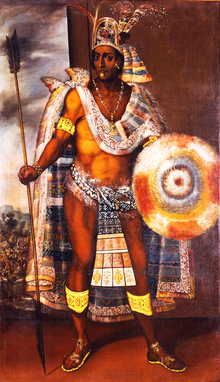

Late 17th-century portrait attributed to Antonio Rodríguez | |

| Reign | 1502/1503–1520 |

| Coronation | 1502/1503 |

| Predecessor | Ahuitzotl |

| Successor | Cuitláhuac |

| King consort of Ecatepec | |

| Tenure | 16th century–1520 |

| Born | c. 1471 |

| Died | 29 June 1520 (aged 48–49) Tenochtitlan, Mexico |

| Consort | |

| Issue Among others |

|

| Father | Axayacatl |

| Mother | Xochicueyetl |

Moctezuma Xocoyotzin[N.B. 1] (c. 1466 – 29 June 1520), referred to retroactively in European sources as Moctezuma II,[N.B. 2] was the ninth Emperor of the Aztec Empire (also known as the Mexica Empire),[1] reigning from 1502 or 1503 to 1520. Through his marriage with Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin of Ecatepec, one of his two wives, he was also king consort of that altepetl.[2]

The first contact between the indigenous civilizations of Mesoamerica and Europeans took place during his reign. He was killed during the initial stages of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire when conquistador Hernán Cortés and his men fought to take over the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan. During his reign, the Aztec Empire reached its greatest size. Through warfare, Moctezuma expanded the territory as far south as Xoconosco in Chiapas and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and incorporated the Zapotec and Yopi people into the empire.[3] He changed the previous meritocratic system of social hierarchy and widened the divide between pipiltin (nobles) and macehualtin (commoners) by prohibiting commoners from working in the royal palaces.[3]

Though two other Aztec rulers succeeded Moctezuma after his death, their reigns were short-lived and the empire quickly collapsed under them. Historical portrayals of Moctezuma have mostly been colored by his role as ruler of a defeated nation, and many sources have described him as weak-willed, superstitious, and indecisive.[4] Depictions of his person among his contemporaries, however, are divided; some depict him as one of the greatest leaders Mexico had, a great conqueror who tried his best to maintain his nation together at times of crisis,[5] while others depict him as a tyrant who wanted to take absolute control over the whole empire.[6] Accounts of how he died and who were the perpetrators (Spaniards or natives) differ. His story remains one of the most well-known conquest narratives from the history of European contact with Native Americans, and he has been mentioned or portrayed in numerous works of historical fiction and popular culture.

Name

The Classical Nahuatl pronunciation of his name is [motɛːkʷˈs̻oːmaḁ]. It is a compound of a noun meaning 'lord' and a verb meaning 'to frown in anger', and so is interpreted as 'he frowns like a lord'[8] or 'he who is angry in a noble manner'.[9] His name glyph, shown in the upper left corner of the image from the Codex Mendoza below, was composed of a diadem (xiuhuitzolli) on straight hair with an attached earspool, a separate nosepiece, and a speech scroll.[10]

Regnal number

The Aztecs did not use regnal numbers; they were given retroactively by historians to more easily distinguish him from the first Moctezuma, referred to as Moctezuma I.[4] The Aztec chronicles called him Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, while the first was called Motecuhzoma Ilhuicamina or Huehuemotecuhzoma ('Old Moctezuma'). Xocoyotzin (IPA: [ʃoːkoˈjoːt͡sin̥]) means 'honored young one' (from xocoyotl 'younger son' + suffix -tzin added to nouns or personal names when speaking about them with deference).[11]

Biography

Ancestry and early life

Moctezuma II was the great-grandson of Moctezuma I through his daughter Atotoztli II and her husband Huehue Tezozómoc (not to be confused with the Tepanec leader). According to some sources, Tezozómoc was the son of emperor Itzcóatl, which would make Moctezuma his great-grandson, but other sources claim that Tezozómoc was Chimalpopoca's son, thus nephew of Itzcóatl, and a lord in Ecatepec.[12] Moctezuma was also Nezahualcóyotl's grandson; he was a son of emperor Axayácatl and one of Nezahualcóyotl's daughters, Izelcoatzin or Xochicueyetl.[13][14] Two of his uncles were Tízoc and Ahuizotl, the two previous emperors.[15]

As was customary among Mexica nobles, Moctezuma was educated in the Calmecac, the educational institution for the nobility. He would have been enrolled into the institution at a very early age, likely at the age of five years, as the sons of the kings were expected to receive their education at a much earlier age than the rest of the population.[16] According to some sources, Moctezuma stood out in his childhood for his discipline during his education, finishing his works correctly and being devout to the Aztec religion.[13]

Moctezuma was an already famous warrior by the time he became the tlatoani of Mexico, holding the high rank of tlacatecuhtli (lord of men) and/or tlacochcalcatl (person from the house of darts) in the Mexica military, and thus his election was largely influenced by his military career and religious influence as a priest,[17] as he was also the main priest of Huitzilopochtli's temple.[18]

One example of a celebrated campaign in which he participated before ascending to the throne was during the last stages of the conquest of Ayotlan, during Ahuizotl's reign in the late 15th century. During this campaign, which lasted 4 years, a group of Mexica pochteca merchants were put under siege by the enemy forces. This was important because the merchants were closely related to Ahuizotl and served as military commanders and soldiers themselves when needed. To rescue the merchants, Ahuizotl sent then-prince Moctezuma with many soldiers to fight against the enemies, though the fight was brief, as the people of Ayotlan surrendered to the Mexica shortly after he arrived.[19]

Approximately in the year 1490, Moctezuma obtained the rank of tequihua, which was reached by capturing at least 4 enemy commanders.[13]

Coronation

The year in which Moctezuma was crowned is uncertain. Most historians suggest the year 1502 to be most likely, though some have argued in favor of the year 1503. A work currently held at the Art Institute of Chicago known as the Stone of the Five Suns is an inscription written in stone representing the Five Suns and a date le 11 reed,[clarification needed] which is equivalent to 15 July 1503 in the Gregorian calendar. Some historians believe this to be the exact date on which the coronation took place, as it is also included in some primary sources.[20][21] Other dates have been given from the same year; Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxóchitl states that the coronation took place on 24 May 1503.[22] However, most documents say Moctezuma's coronation happened in the year 1502, and therefore most historians believe this to have been the actual date.[13]

Reign

After his coronation, Moctezuma set up thirty-eight more provincial divisions, largely to centralize the empire. He sent out bureaucrats, accompanied by military garrisons, who made sure tax was being paid, national laws were being upheld and served as local judges in case of disagreement.[23]

Internal policy

Natural disasters

Moctezuma's reign began with difficulties. In the year 1505, a major drought resulted in widespread crop failure, and thus a large portion of the population of central Mexico began to starve. One of the few places in the empire not affected by this drought was Totonacapan, and many people from Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco sought refuge in this region to avoid starvation. Large amounts of maize were brought from this area to aid the population.[24] Moctezuma and the lords of Texcoco and Tlacopan, Nezahualpilli, and Totoquihuatzin, attempted to aid the population during the disaster, including using all available food supplies to feed the population and raising tributes for one year.[25] The drought and famine ultimately lasted three years,[26] and at some point became so severe that some noblemen reportedly sold their children as slaves in exchange for food to avoid starvation. Moctezuma ordered the tlacxitlan, the criminal court of Tenochtitlan (which aside from judging criminals also had the job of freeing "unjustified" slaves), to free those children and offer food to those noblemen.[27] Another natural disaster, of lesser intensity, occurred in the winter of 1514, when a series of dangerous snowstorms resulted in the destruction of various crops and property across Mexico.[28]

Policies and other events during his reign

During his government, he applied multiple policies that centered the government of the empire on his person, though it is difficult to tell exactly to which extent those policies were applied, as the records written about such policies tend to be affected by propaganda in favor of or against his person.[N.B. 3]

According to Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, among Moctezuma's policies were the replacement of a large portion of his court (including most of his advisors) with people he deemed preferable, and increasing the division between the commoner and noble classes, which included the refusal to offer certain honors to various politicians and warriors for being commoners.[30] He also prohibited any commoners or illegitimate children of the nobility from serving in his palace or high positions of government. This was contrary to the policies of his predecessors, who did allow commoners to serve in such positions.[31]

Moctezuma's elitism can be attributed to a long conflict of interests between the nobility, merchants, and warrior class. The struggle occurred as the result of the conflicting interests between the merchants and the nobility and the rivalry between the warrior class and the nobility for positions of power in the government. Moctezuma likely sought to resolve this conflict by installing despotist policies that would settle it.[32] However, it is also true that many of his elitist policies were put in place because he did not want to "work with inferior people", and instead wanted to be served by and interact with people he deemed more prestigious, both to avoid giving himself and the government a bad reputation and to work with people he trusted better.[33] However, some of his policies also affected the nobility, as he had intentions of reforming it so that it would not pose a potential threat to the government; among these policies was the obligation of the nobility to reside permanently in Tenochtitlan and abandon their homes if they lived elsewhere.[34]

Regarding his economic policies, Moctezuma's rule was largely affected by natural disasters in the early years. As mentioned before, the famine during his first years as tlatoani resulted in a temporary increase in tribute in some provinces to aid the population. Some provinces, however, ended up paying more tribute permanently, most likely as the result of his primary military focus shifting from territorial expansion to stabilization of the empire through the suppression of rebellions. Most of the provinces affected by these new tributary policies were in the Valley of Mexico. For example, the province of Amaquemecan, which formed part of the Chalco region, was assigned to pay an additional tribute of stone and wood twice or thrice a year for Tenochtitlan's building projects.[35] This tributary policy eventually backfired, as some of the empire's subjects grew disgruntled with Moctezuma's government and launched rebellions against him, which eventually resulted in many of these provinces—including Totonacapan (under the de facto leadership of Chicomacatl), Chalco and Mixquic (which were near Tenochtitlan)—forming alliances with Spain against him.[36]

The famine at the beginning of his rule also resulted in the abolishment of the huehuetlatlacolli system, which was a system of serfdom in which a family agreed to maintain a tlacohtli (slave or serf) perpetually. This agreement also turned the descendants of the ones who agreed into serfs.[34]

During his campaign against Jaltepec and Cuatzontlan (see below), he made negotiations with the Tlatelolca to obtain the weapons and resources needed. As a result of these negotiations, Tlatelolco was given more sovereignty; they were permitted to rebuild their main temple which was partially destroyed in the Battle of Tlatelolco in a civil war during Axayácatl's reign, act largely independently during military campaigns, and be absolved from paying tribute.[37][31]

Many of these policies were planned together with his uncle Tlilpotonqui, cihuacoatl of Mexico and son of Tlacaelel, at the beginning of his reign,[33] while others, such as his tributary policies, were created as the result of various events, like the famine which occurred at the beginning of his rule. His policies, in general, had the purpose of centralizing the government in his person through the means of implementing policies to settle the divide between the nobility and commoners and abolishing some of the more feudal policies of his predecessors, while also making his tributary policies more severe to aid the population during natural disasters and to compensate for a less expansionist focus in his military campaigns.[34]

Most of the policies implemented during his rule would not last long after his death, as the empire fell into Spanish control on 13 August 1521 as a result of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, one year after he died.[38] The new Spanish authorities implemented their laws and removed many of the political establishments founded during the pre-Hispanic era, leaving just a few in place. Among the few policies that lasted was the divide between the nobility and the commoners, as members of the pre-Hispanic nobility continued to enjoy various privileges under the Viceroyalty of New Spain, such as land ownership through a system known as cacicazgo.[39][40]

Construction projects

Moctezuma, like many of his predecessors, built a tecpan (palace) of his own. This was a particularly large palace, which was somewhat larger than the National Palace that exists today which was built over it, being about 200 meters long and 200 meters wide. However, little archaeological evidence exists to understand what his palace looked like, but the various descriptions of it and the space it covered have helped reconstruct various features of its layout. Even so, these descriptions tend to be limited, as many writers were unable to describe them in detail. The Spanish captain Hernán Cortés, the main commander of the Spanish troops that entered Mexico in the year 1519, himself stated in his letters to the king of Spain that he would not bother describing it, claiming that it "was so marvelous that it seems to me impossible to describe its excellence."[41]

The palace had a large courtyard that opened into the central plaza of the city to the north, where Templo Mayor was. This courtyard was a place where hundreds of courtiers would hold multiple sorts of activities, including feasts and waiting for royal business to be conducted. This courtyard had suites of rooms that surrounded smaller courtyards and gardens.[41]

His residence had many rooms for various purposes. Aside from his room, at the central part of the upper floor, there were two rooms beside it which were known as coacalli (guest house). One of these rooms was built for the lords of Tlacopan and Texcoco, the other two members of the Triple Alliance, who came to visit. The other room was for the lords of Colhuacan, Tenayohcan (today known as Tenayuca) and Chicuhnautlan (today, Santa María Chiconautla). The exact reason why this room had this purpose remains uncertain, though a few records like Codex Mendoza say the reason was that these lords were personal friends of Moctezuma. There was also another room which became known as Casa Denegrida de Moctezuma (Spanish: Moctezuma's Black House), a room with no windows and fully painted black which was used by Moctezuma to meditate. Remains of this room have been found in recent years in modern Mexico City.[42] The upper floor had a large courtyard which was likely used as a cuicacalli, for public shows during religious rituals. The bottom floor had two rooms which were used by the government. One of them was used for Moctezuma's advisors and judges who dealt with the situations of the commoners (likely the Tlacxitlan). The other room was for the war council (likely the Tequihuacalli), where high-ranking warriors planned and commanded their battles.[43]

As part of the construction of Moctezuma's palace, various projects were made which made it more prestigious by providing entertainment to the public.

One of the most famous among these projects was the Totocalli (House of Birds), a zoo which had multiple sorts of animals, mainly avian species, but also contained several predatory animals in their section. These animals were taken care of by servants who cleaned their environments, fed them, and offered them care according to their species. The species of birds held within the zoo were widely varied, holding animals like quetzals, eagles, true parrots, and others, and also included water species like roseate spoonbills and various others that had their pond.[44][45]

The section with animals other than birds, which was decorated with figures of gods associated with the wild, was also considerably varied, having jaguars, wolves, snakes, and other smaller predatory animals. These animals were fed on hunted animals like deer, turkeys, and other smaller animals. Allegedly, the dead bodies of sacrificial victims were also used to feed these animals, and after the battle known as La Noche Triste, which occurred during the early stages of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in June 1520 (during which Moctezuma died), the bodies of dead Spaniards may have been used to feed them.[46]

This place was highly prestigious, and all sorts of important people are said to have used to visit this place, including artists, craftsmen, government officials, and blacksmiths.[45]

The Totocalli, however, was burnt and destroyed, along with many other constructions, in the year 1521 during the Siege of Tenochtitlan, as the Spanish captain Hernán Cortés ordered for many of the buildings that formed part of the royal palaces to be burnt to demoralize the Mexica army and civilians. Though Cortés himself admitted that he enjoyed the zoo, he stated that he saw it as a necessary measure in his third letter to King Charles I of Spain.[47]

Another construction was the Chapultepec aqueduct, built in 1506 to bring fresh water directly from Chapultepec to Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco.[24] This water was driven to the merchant ports of the city for people to drink and to the temples.[48] This aqueduct was destroyed less than a year after Moctezuma's death, during the Siege of Tenochtitlan in 1521, as the Spaniards decided to destroy it to cut Tenochtitlan's water supply. Some Mexica warriors attempted to resist its destruction, but were repelled by the Tlaxcalan allies of the Spanish.[49]

Territorial expansion during his rule, military actions and foreign policy

At the beginning of his rule, he attempted to build diplomatic ties with Tlaxcala, Huexotzinco (today, Huejotzingo), Chollolan (Cholula), Michoacan, and Metztitlán, by secretly inviting the lords of these countries to attend the celebrations for his coronation before the continuation of the flower wars, which were wars of religious nature arranged voluntarily by the parties involved with no territorial purposes, but instead to capture and sacrifice as many soldiers as possible. During this period, Mexico and Tlaxcala still were not at war, but the tension between these nations was high, and the embassy sent for this purpose was put in a highly risky situation, for which reason Moctezuma chose as members of the embassy only experts in diplomacy, espionage, and languages. Fortunately, his invitation was accepted, and Moctezuma used this opportunity to show his greatness to the lords who attended. However, because the invitation was secret to avoid a scandal for inviting his rivals to this ceremony, Moctezuma ordered that no one should know that the lords were present, not even the rulers of Tlacopan (today known as Tacuba) and Texcoco, and the lords saw themselves often forced to pretend to be organizers to avoid confusion.[50] Though Moctezuma would continue to hold meetings with these people, where various religious rituals were held, it did not take long for large-scale conflicts to erupt between these nations.

An important thing to note is that contrary to popular belief, Tlaxcala was not Mexico's most powerful rival in the central Mexican region in this period, and it would not be so until the final years of pre-Hispanic Mexico in 1518–19. In the opening years of the 16th century, Huejotzingo was Mexico's actual military focus, and it proved itself to be one of the most powerful political entities until these final years, as a series of devastating wars weakened the state into being conquered by Tlaxcala.[51]

During his reign, he married the queen of Ecatepec, Tlapalizquixochtzin,[2] making him king consort of this altepetl, though according to the chronicle written by Bernal Díaz del Castillo, very few people in Mexico knew about this political role, being only a few among his closest courtiers among those who knew.[52]

Early military campaigns

The first military campaign during his rule, which was done in honor of his coronation, was the violent suppression of a rebellion in Nopala and Icpatepec. For this war, a force of over 60,000 soldiers from Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, Tepanec lands, Chalco, and Xochimilco participated, and Moctezuma himself went to the frontlines. Approximately 5100 prisoners were taken after the campaign, many of whom were given to inhabitants of Tenochtitlan and Chalco as slaves, while the rest were sacrificed in his honor on the fourth day of his coronation. In Nopala, Mexica soldiers committed a massacre and burned down the temples and houses, going against Moctezuma's wishes.[53] After the campaign, celebrations for his coronation continued in Tenochtitlan.[54] Moctezuma's territorial expansion, however, would not truly begin until another rebellion was suppressed in Tlachquiauhco (today known as Tlaxiaco), where its ruler, Malinalli, was killed after trying to start the rebellion. In this campaign, all adults above the age of 50 within the city were killed under Moctezuma's orders as he blamed them for the rebellion.[55] A characteristic fact about Moctezuma's wars was that a large portion of them had the purpose of suppressing rebellions rather than conquering new territory, contrary to his predecessors, whose main focus was territorial expansion.[17]

Rebellions

During his reign, multiple rebellions were suppressed by the use of force and often ended with violent results. As mentioned previously, the first campaign during his reign, which was done in honor of his coronation, was the suppression of a rebellion in Nopallan (today known as Santos Reyes Nopala) and Icpatepec (a Mixtec town that no longer exists which was near Silacayoapam), both in modern-day Oaxaca.[20] The prisoners taken during this campaign were later used as slaves or for human sacrifice.

After Mexico suffered a humiliating defeat at Atlixco during a flower war against Huejotzingo (see below), many sites in Oaxaca rebelled, likely under the idea that the empire's forces were weakened. However, Moctezuma was able to raise an army numbering 200,000 and marched over the city of Yancuitlan (today known as Yanhuitlan), a city which had been previously conquered by Tizoc, and conquered Zozollan in the process. Abundant territorial expansion was carried out following this.[56]

Another notable rebellion occurred in Atlixco (in modern-day Puebla), a city neighboring Tlaxcala which had previously been conquered by Ahuizotl.[17] This rebellion occurred in 1508, and was repressed by a prince named Macuilmalinatzin.[25] This wasn't the first conflict that occurred in this region, as its proximity with Tlaxcala and Huejotzingo would cause multiple conflicts to erupt in this area during Moctezuma's reign.

A large series of rebellions occurred in 1510, likely as a result of astrological predictions halting some Mexica military operations to a degree. Moctezuma would try to campaign against these rebellions one at a time throughout the following years, campaigning against territories in Oaxaca, including Icpatepec again, in 1511 or 1512.[57] Some of these revolts occurred as far south as Xoconochco (today known as Soconusco) and Huiztlan (today, Huixtla), far down where the Mexican-Guatemalan border is today. These territories were highly important to the empire and had been previously conquered by his predecessor Ahuizotl, thus Moctezuma had to maintain them under his control.[58] These revolts occurred in so many locations that the empire was unable to deal with all of them effectively.

Territorial expansion

The empire's expansion during Moctezuma's rule was mainly focused on southwestern Mesoamerican territories, in Oaxaca and modern-day Guerrero. The earliest conquests in this territory were held by Moctezuma I.

The first important conquest during Moctezuma's rule occurred in the year 1504 when the city of Achiotlan (today known as San Juan Achiutla) was conquered. This war, according to some sources, was supposedly mainly caused by "a small tree which belonged to a lord of the place which grew such beautiful flowers Moctezuma's envy couldn't resist it", and when Moctezuma asked for it, the lord of the city refused to offer it, thus starting the war. After the conquest, this tree was supposedly taken to Tenochtitlan. The second conquest occurred in Zozollan, a place neighboring east of Achiutla, on 28 May 1506, during the campaign against the Yanhuitlan rebellion. This conquest had a particularly violent result, as a special sacrifice was held after the campaign where the prisoners captured in Zozollan were the victims. "The Mexicans killed many of the people from Zozola [sic] which they captured in war", according to old sources.[weasel words][59]

In the year 1507, the year of the New Fire Ceremony, abundant military action occurred. Among the towns that are listed to have been conquered this year are: Tecuhtepec (from which multiple prisoners were sacrificed for the ceremony), Iztitlan, Nocheztlan (an important town northeast of Achiutla), Quetzaltepec, and Tototepec.[59]

The conquest of Tototepec formed part of the conquests of some of the last few Tlapanec territories of modern-day Guerrero, an area which had already been in decline since Moctezuma I began his first campaigns in the region and probably turned the Kingdom of Tlachinollan (modern-day Tlapa) into a tributary province during the rule of Lord Tlaloc between 1461 and 1467 (though the kingdom would not be invaded and fully conquered until the reign of Ahuizotl in 1486, along with Caltitlan, a city neighboring west of Tlapa). In between the years of 1503 and 1509, a campaign was launched against Xipetepec, and another was launched (as mentioned previously) in 1507 against Tototepec, which had previously been a territory conquered by Tlachinollan in the mid-14th century. The campaign in Tototepec occurred as the result of a large group of Mexica merchants sent by Moctezuma being killed after they attempted to trade for some of the resources of the area on his behalf.[60] During the conquest of Tototepec, two important Mexica noblemen, Ixtlilcuechahuac and Huitzilihuitzin (not to be confused with the tlatoani of this name), were killed.[25] All the population of Tototepec, except for the children, was massacred by the Mexica forces, and about 1350 captives were taken.[61] Another campaign was launched in 1515 to conquer Acocozpan and Tetenanco and reconquer Atlitepec, which had been previously conquered by Ahuizotl in 1493.[62]

Quetzaltepec was conquered on the same campaign as Tototepec, as both reportedly murdered the merchants sent by Moctezuma in the area. The Mexica managed to raise an army of 400,000 and first conquered Tototepec. Quetzaltepec was also conquered, but it rebelled along with various sites across Oaxaca soon after when the Mexica lost the Battle of Atlixco against Huejotzingo. Being a fortified city with six walls, the Mexica put the city under siege for several days, with the each of groups of the Triple Alliance attacking from various locations and having over 200 wooden ladders constructed under Moctezuma's orders. The Mexica eventually emerged victorious, successfully conquering the city.[63]

Several military defeats occurred in some of these expansionist campaigns, however, such as the invasion of Amatlan in 1509, where an unexpected series of snowstorms and blizzards killed many soldiers, making the surviving ones too low in numbers to fight.[57]

An important campaign was the conquest of Xaltepec (today known as Jaltepec) and Cuatzontlan and the suppression of the last revolt in Icpatepec, all in Oaxaca. This war started as the result of provocations given by Jaltepec against Moctezuma through killing as many Mexicas as they could find in their area, as some sort of way to challenge him, and the beginning of the revolt by Icpatepec as the result. The Xaltepeca had done this before with previous tlatoanis and other nations. Moctezuma and the recently elected ruler of Tlacopan themselves went to the fight, along with Tlacaelel's grandson and cihuacoatl of Mexico in this period Tlacaeleltzin Xocoyotl.[64] A large portion of the weapons and food was brought by Tlatelolco, though they were initially hesitant to do so, but were ordered by Moctezuma to offer it as a tribute to Tenochtitlan, and they received multiple rewards as the result, including the permission to rebuild their main temple (which had been partially destroyed during the Battle of Tlatelolco which occurred during Axayacatl's reign). This campaign had a highly violent result; Moctezuma, after receiving information on the cities gathered by his spies, ordered for all adults in the sites above the age of 50 to be killed to prevent a rebellion once the cities were conquered, similar to the war in Tlachquiauhco. The conquest was done by dividing the army that was brought in 3 divisions; one from Tlacopan, one from Texcoco, and one from Tenochtitlan, so that each one attacked a different city. The Tenochtitlan company attacked Jaltepec. Moctezuma came out victorious and then returned to Mexico through Chalco, where he received many honors for his victory.[65] This war likely happened in 1511, as a war against Icpatepec is recorded to have happened again in that year.[59]

After the campaigns in the Oaxaca region, Moctezuma began to move his campaigns into northern and eastern territories around 1514, conquering the site of Quetzalapan, a Chichimec territory through the Huastec region, taking 1332 captives and suffering minimal casualties, with only 95 reported losses. Likely around this time, many other territories in the region were also conquered. He also went to war against the Tarascan Empire for the first time since Axayácatl was defeated in his disastrous invasion. This war caused high casualties on both sides. The Mexica succeeded at taking a large amount of captives, but failed to conquer any territory.[66]

Among the final military campaigns carried out by Moctezuma, aside from the late stages of the war against Tlaxcala, were the conquests of Mazatzintlan and Zacatepec, which formed part of the Chichimec region.[67]

The approximate number of military engagements during his rule before European contact was 73, achieving victory in approximately 43 sites (including territories already within the empire),[59] making him one of the most active monarchs in pre-Hispanic Mexican history in terms of military actions.[17]

However, his rule and policies suffered a very sudden interruption upon the news of the arrival of Spanish ships in the east in 1519 (see below).

Texcoco crisis

One of the most controversial events during his reign was the supposed overthrow of the legitimate government of Nezahualpilli in Texcoco. Historians such as Alva Ixtlilxóchitl even went as far as referring to this action as "diabolical", while also making claims that are not seen in other chronicles and are generally not trusted by modern historians.[68][N.B. 3]

Nezahualpilli's death

The circumstances of Nezahualpilli's death are not clear, and many sources offer highly conflicting stories about the events that resulted in it.

According to Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, the issue began when Moctezuma sent an embassy to Nezahualpilli reprimanding him for not sacrificing any Tlaxcalan prisoners since the last 4 years, during the war with Tlaxcala (see below), threatening him saying that he was angering the gods. Nezahualpilli replied to this embassy stating that the reason he had not sacrificed them was that he simply did not want to wage war because he and his population wanted to live peacefully for the time being, as the ceremonies that would be held in the following year, 1 reed, would make war inevitable, and that soon his wishes would be granted. Eventually, Nezahualpilli launched a campaign against Tlaxcala, though he did not go himself, instead sending two of his sons, Acatlemacoctzin and Tecuanehuatzin, as commanders. Moctezuma then decided to betray Nezahualpilli by sending a secret embassy to Tlaxcala telling them about the incoming army. The Tlaxcalans then began to take action against the Texcoca while they were unaware of this betrayal. The Texcoco armies were ambushed in the middle of the night. Almost none of the Texcoca survived the fight. Upon receiving the news of Moctezuma's betrayal, understanding that nothing could be done about it and fearing for the future of his people, Nezahualpilli committed suicide in his palace.[69]

This story, however, as mentioned before, is not generally trusted by modern historians, and much of the information given contradicts other sources.

Sources do agree, however, that Nezahualpilli's last years as ruler were mainly characterized by his attempts to live a peaceful life, likely as the result of his old age. He spent his last months mostly inactive in his rule and his advisors, on his request, took most of the government's decisions during this period. He assigned two men (of whom details are mostly unknown) to take control of almost all government decisions. These sources also agree that he was found dead in his palace, but the cause of his death remains uncertain.[70]

His death is recorded to have been mourned in Texcoco, Tenochtitlan, Tlacopan, and even Chalco and Xochimilco, as all of these altepeme gave precious offerings, like jewelry and clothes, and sacrifices in his honor. Moctezuma himself was reported to have broken into tears upon receiving the news of his death. His death was mourned for 80 days. This was recorded as one of the largest funeral ceremonies in pre-Hispanic Mexican history.[71]

Succession crisis

Elections

Since Nezahualipilli died abruptly in the year 1516, he left no indication as to who his successor would be. He had six legitimate sons: Cacamatzin, Coanacochtli (later baptized as Don Pedro), Tecocoltzin (baptized as Don Hernando), Ixtlilxochitl II (baptized as Don Hernando), Yoyontzin (baptized as Don Jorge) and Tetlahuehuetzquititzin (baptized as Don Pedro), all of whom would eventually take the throne, though most of them after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire.[72] His most likely heir was Tetlahuehuetzquititzin, as he was the wealthiest among Nezahualpilli's sons, but he was considered inept for the job. His other most likely heirs were Ixtlilxochitl, Coanacochtli, and Cacamatzin, though not everyone supported them as they were considerably younger than Tetlahuehuetzquititzin, as Ixtlilxochitl was 19 years old and Cacamatzin was about 21.[73] Moctezuma supported Cacamatzin since he was his nephew. In the end, the Texcoco council voted in favor of Moctezuma's decision, and Cacamatzin was declared tlatoani, being that he was the son of Moctezuma's sister Xocotzin and was older than his two other brothers. Though Coanacochtli felt the decision was fair, Ixtlilxochitl disagreed with the results and protested against the council.[74] Ixtlilxochitl argued that the reason why Moctezuma supported Cacamatzin was because he wanted to manipulate him so that he could take over Texcoco, being that he was his uncle. Coanacochtli responded that the decision was legitimate and that even if Cacamatzin was not elected Ixtlilxochitl would not have been elected either, as he was younger than the two. Cacamatzin stayed quiet during the whole debate. Eventually, the members of the council shut down the debate to prevent a violent escalation. Though Cacamatzin was officially declared tlatoani, the coronation ceremony didn't occur that day, and Ixtlilxochitl used this as an opportunity to plan his rebellion against him.[75]

Ixtlilxóchitl's rebellion

Shortly after the election, Ixtlilxochitl began to prepare his revolt by going to Metztitlán to raise an army, threatening civil war. Cacamatzin went to Tenochtitlan to ask Moctezuma for help. Moctezuma, understanding Ixtlilxochitl's war-like nature, decided to support Cacamatzin with his military forces should a conflict begin and try to talk Ixtlilxochitl into stopping the conflict, and also suggested taking Nezahualpilli's treasure to Tenochtitlan to prevent a sacking. According to Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, Cacamatzin asked Moctezuma for help after Ixtlilxochitl went to Metztitlán,[76] while other sources claim that Ixtlilxochitl went to Metztitlán because of Cacamatzin's visit to Moctezuma.[77]

Ixtlilxochitl first went to Tulancingo with 100,000 men, where he was received with many honors and recognized as the real king of Texcoco. He then accelerated his pace, possibly because he received worrying news from Texcoco, and advanced to the city of Tepeapulco, where he was also welcomed. He soon advanced to Otompan (today known as Otumba, State of Mexico), where he sent a message before his entrance in hopes of being received as a king there as well. However, the people of Otumba supported Cacamatzin and informed Ixtlilxochitl that such a demand would not be fulfilled. Ixtlilxochitl therefore sent his troops to invade the city, and after a long fight the troops began to gradually retreat and its ruler was killed. When the news of this fight was heard in Texcoco, all events, religious or not, were canceled, soldiers were recruited, troops were sent from Tenochtitlan to the city and Cacamatzin and Coanacochtli fortified the city to avoid an invasion.[78]

He eventually reached Texcoco and placed the city under siege, while also occupying the cities of Papalotlan, Acolman, Chicuhnautlan (today known as Santa María Chiconautla), Tecacman, Tzonpanco (Zumpango), and Huehuetocan to take every possible entrance Moctezuma could use to send his troops to Texcoco. Moctezuma, however, used his influence to enter the city of Texcoco and obtain access to the Acolhua cities not yet occupied by Ixtlilxochitl. Cacamatzin used this opportunity to send a commander from Iztapalapa named Xochitl to arrest Ixtlilxochitl as peacefully as possible. Moctezuma approved this decision and Xochitl was sent along with some troops. Ixtlilxochitl was quickly informed about this and, as per the custom of war, informed Xochitl that he was going to fight him. A short battle occurred some time after in which Xochitl was captured and later publicly executed by burning. Once the news of this defeat was heard by Moctezuma, he ordered that no more military engagements be done for the moment to prevent further escalation and that he wanted to rightfully punish Ixtlilxochitl for what he did at a more appropriate moment. In the meantime, the brothers agreed to try to reach a consensus through a peaceful debate, as Ixtlilxochitl did not want to fight either, as he claimed that he only sent the troops as a means of protest and not to wage war.[79] However, this would only be done under the condition that Moctezuma would not get involved by any means.[80] The three brothers then agreed to divide the province of Acolhuacan (where Texcoco was the de facto capital) in three parts, one for each brother, and that Cacamatzin would continue to rule over Texcoco.[81]

At some point, however, Ixtlilxochitl sought refuge outside of Texcoco to avoid facing a conflict with Cacamatzin.[82]

Spanish involvement

This crisis would later become relevant again after the Spanish arrived at Tenochtitlan, when Cacamatzin, who initially welcomed the Spaniards when they first entered in November 1519, attempted to raise an army against them for imprisoning Moctezuma (see below) by calling for the people of Coyoacan, Tlacopan, Iztapalapa and the Matlatzinca people to enter the city, kill the Spaniards and free Moctezuma in early 1520. The Spanish captain Hernán Cortés, who was the main commander of the Spanish troops who entered Mexico, decided to act and ordered Moctezuma to send someone to arrest Cacamatzin before the attack. Moctezuma suggested that Ixtlilxochitl be sent due to the crisis, as then he could take the throne and prevent another succession crisis. He still tried to establish negotiations between the Texcoco leadership and the Spaniards but was unable to change Cacamatzin's mind. Eventually, Moctezuma sent troops to secretly arrest Cacamatzin in his palace and send him to Mexico after he ordered for three of his commanders to be arrested for suggesting requesting Mocetzuma's permission for the attack and telling him that there was no chance of entering into negotiations with the Spaniards. Ixtlilxochitl became the likely de facto leader of Texcoco afterwards,[83] though according to Bernardino de Sahagún, it was Tecocoltzin who officially took the title of tlatoani after Cacamatzin's arrest and Ixtlilxochitl would not officially become the tlatoani until a year later.[84]

Ixtlilxochitl continued fighting for the Spaniards afterwards, became a personal friend of Cortés, converted to Christianity and participated in the Spanish conquest of Honduras in 1525.[84] His figure has remained controversial in the historical record, as some have seen him as a man who betrayed his people for his ambition,[85] while others have seen him as a brave warrior who fought against the tyrannical rule of Moctezuma II and liberated the peoples he subjugated with the help of Hernán Cortés.[86]

War with Tlaxcala, Huejotzingo and their allies

Though the first conflicts between Mexico and Tlaxcala, Huejotzingo, and their allies began during the rule of Moctezuma I in the 1450s, it was during the reign of Moctezuma II that major conflicts broke through.

Battle of Atlixco

| Battle of Atlixco | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the flower wars | |||||||

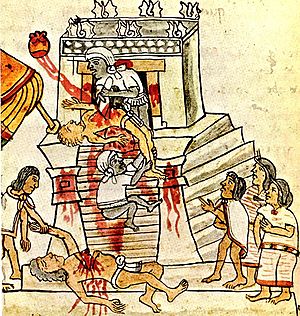

The defeat suffered at the battle of Atlixco against Huejotzingo, according to the Durán Codex | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Huejotzingo | ||||||

| Supported by: | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Tecayahuatzin(?) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 100,000 warriors | Unknown (possibly 100,000 warriors) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

Planning and preparations

Approximately in the year 1503 (or 1507, after the conquest of Tototepec, according to historian Diego Durán),[87] a massive battle occurred in Atlixco which was fought mainly against Huejotzingo, a kingdom that used to be one of the most powerful ones in the Valley of Mexico.[88] The war was provoked by Moctezuma himself, who wanted to go to war against Huejotzingo because it had been many months since the last war. The local rulers of the region accepted Moctezuma's proposal to wage this war. It was declared as a flower war, and the invitation to go to war was accepted by the people of Huejotzingo, Tlaxcala, Cholula, and Tliliuhquitepec, a city-state nearby. The war was arranged to occur in the plains of Atlixco. Moctezuma went to the fight along with four or five of his brothers and two of his nephews.[89]

He named one of his brothers (or children, according to some sources),[90] Tlacahuepan, as the main commander of the troops against the troops of Huejotzingo. He was assigned 100,000 troops to fight. Tlacahuepan decided to begin the fight by dividing the troops into three groups which would attack one after the other, the first being the troops from Texcoco, then from Tlacopan, and lastly from Tenochtitlan.

Battle

He began by sending 200 troops to launch skirmishes against the Huexotzinca, but despite the large numbers and skirmishes, he was unable to break the enemy lines. The group of Texcoco suffered huge losses and once they were unable to fight they were put to rest while the group from Tlacopan was sent. However, they were still unable to break the lines. The Tenochca group then advanced and pushed to aid the Tepanecs of Tlacopan, causing multiple casualties against the Huexotzinca, but the lines were still not broken as more reinforcements arrived. Eventually, Tlacahuepan saw himself surrounded, and though he initially resisted, he finally surrendered. Though the Huexotzinca wanted to take him alive, he asked to be sacrificed there on the battlefield, and so he was killed, and then the rest of the Mexica troops retreated.[91] The result of this battle was considered humiliating for the empire. According to primary records, about 40,000 people were killed on both sides (possibly meaning that about 20,000 died on each side).[92] Some important Mexica noblemen were also killed during the engagement, including Huitzilihuitzin (not to be confused with the tlatoani of this name), Xalmich and Cuatacihuatl.

Aftermath

Regardless, multiple prisoners were taken after the fight, who were later sacrificed in Moctezuma's honor.[89] Tlacahuepan was remembered as a hero despite the loss, and many songs were dedicated to him to be remembered through poetry. In one song called Ycuic neçahualpilli yc tlamato huexotzinco. Cuextecayotl, Quitlali cuicani Tececepouhqui (The song of Nezahualpilli when he took captives in Huexotzinco. [It tells of] the Huastec themes, it was written down by the singer Tececepouhqui), he's referred as "the golden one, the Huastec lord, the owner of the sapota skirt", about the god Xipe Totec, and also states "With the flowery liquor of war, he is drunk, my nobleman, the golden one, the Huastec Lord", about his Huastec heritage, using the stereotype that the Huastecs were drunkards.[93] Anyway, the defeat was a humiliating one, and Moctezuma is said to have cried in anguish upon hearing of the death of Tlacahuepan and the massive loss of soldiers. Moctezuma himself welcomed the soldiers who survived back into Mexico, while the population that welcomed them mourned.[94]

The fact that the Huexotzinca also suffered massive casualties caused their military power to be highly weakened by this battle and various others, and so this could be seen as the beginning of the fall of Huejotzingo, as multiple military losses against Tlaxcala and Mexico in the following years eventually led to its fall, despite the victory in the fight.[95]

Other battles against Huejotzingo and its allies

Various other battles occurred in the following years between Mexico and Huejotzingo, and though none of them were as big as the Battle of Atlixco, they still caused significant losses on both sides; high losses for Mexico and significant losses for Huejotzingo.

An engagement which occurred likely in the year of 1506. This fight was another flower war which was proposed by Cholula, with support from Huejotzingo, to be fought in Cuauhquechollan (today known as Huaquechula, in modern-day Puebla), near Atlixco. Though Moctezuma did not want to fight as a result of the previous defeat in Atlixco, he saw no other option and prepared for the fight. In this fight, warriors from Texcoco, Tlacopan, Chalco, Xochimilco, and modern-day Tierra Caliente participated. This battle reportedly ended with 8200 Mexicas killed or captured. However, the Mexica are said to have dealt a similar number of casualties in this one-day battle. The result of this battle was indecisive, as some reported it as a victory, but it seems Moctezuma II took it as a defeat and was highly upset about it, to the point that he complained against the gods.[96]

Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc, however, reports that 10,000 Mexicas died in this fight and that the Mexica were so angry about the fight that they called for reinforcements who committed a "cruel slaughter" and captured 800 more enemies. He lists the number of Huexotzinco-Cholula casualties as 5600 killed and 400 captured in one other engagement afterwards, which resulted in 8200 Mexicas killed or captured.[92]

Invasion of Tlaxcala

Initial stages

It was approximately in the year 1504 or 1505 when the first large-scale conflicts between Mexico and Tlaxcala began. In this period, Moctezuma thought about placing the entire country under siege, understanding that most of it was surrounded by territories belonging to the empire. The ruler of Huejotzingo, Tecayahuatzin, sympathized with Moctezuma despite their connections with Tlaxcala and conflicts in the past, and through bribes and propaganda attempted to ally with Cholula and local Otomi populations to attack Tlaxcala, though with little success. The Tlaxcalans became greatly worried about this and began to grow suspicious of all allies they had fearing a betrayal, as Huejotzingo was one of Tlaxcala's closest states, as proven by its support at the battle of Atlixco. Moctezuma, however, had the disadvantage that many of his dominions surrounding Tlaxcala did not want to fight them, as many of them used to be their allies in the past even with all the promises Moctezuma made, and therefore his support was actually quite limited.

One of the first battles occurred in Xiloxochitlan (today known as San Vicente Xiloxochitla), where multiple atrocities were committed. Despite this, the Tlaxcalan resistance managed to hold out, and after a great struggle, the Huexotzinca armies were repelled, though during the fight the Ocotelolca commander Tizatlacatzin was killed. Many other smaller battles took place in other parts of the border, though none of them were successful.[97]

In response, Tlaxcala launched a counter-invasion against Huejotzingo, knowing that the Huexotzinca had been severely weakened by their fights with the Mexica Empire;[98] their towns were sacked repeatedly and the entire nation was put essentially under siege, and the remains of the nation were now cornered in the region around the Popocatépetl. The Huexotzinca became greatly worried and knew they couldn't win the war alone, therefore a prince named Teayehuatl decided to send an embassy to Mexico to request aid against the Tlaxcalans. According to historians like Durán, this embassy was sent in the year 1507, just after the New Fire Ceremony, while others date this embassy to the year 1512.[99] The embassy informed Moctezuma about the Tlaxcalan counter-invasion, which had been happening for over a year by this point, requesting Moctezuma to do something about the situation to expel the Tlaxcalans from their land. This was not the first time the Huexotzinca had requested aid from Mexico for similar reasons, as the first time was actually around the year 1499, during the reign of Ahuizotl, though this previous request was denied.[100] After consulting Nezahualpilli and the ruler of Tlacopan, Moctezuma agreed to help the Huexotzinca, despite the conflicts they had in the past, and sent a large number of soldiers to help this nation,[101] while also allowing many of their refugees to stay in Tenochtitlan and Chalco.[99]

Late stages

With the Mexica forces to support Huejotzingo, the invasion continued from the west with the main force from the towns of Cuauhquechollan, Tochimilco, Itzocan (today known as Izúcar de Matamoros), and a smaller support force from a town named Tetellan (today, Tetela de Ocampo) and from a town named Chietla. The advance was quick, but the Tlaxcalans used the territories they had captured from Huejotzingo to advance safely to Atlixco through the captured areas with little population before the Mexica-Huejotzingo forces spread.[102] Once done, a long fight began between the two forces. The battle lasted 20 days, and both armies suffered huge losses, as the Tlaxcalans had a famous general captured and the Mexica lost so many men that they requested emergency reinforcements, asking for "all kinds of people in the shortest possible time". The Tlaxcalans claimed victory in that fight, and the Mexica were fought into a complete standstill.[99] The following year, Huejotzingo started to suffer a famine as the result of a lack of resources as the Tlaxcalans pushed further into their territory. The Tlaxcalans even went as far as burning down the royal palaces of Huejotzingo and stealing as much food as they could.[103]

Approximately in the year 1516, Huejotzingo abandoned its alliance with the empire.[100]

The devastating wars that broke out against Huejotzingo caused this nation, which had been the most powerful nation in the Valley of Puebla in the opening years of the 16th century, to become weak enough to be conquered by Tlaxcala. This was the point at which Tlaxcala became Mexico's most powerful rival in the central Mexican area. The nation which used to be their main military focus was now the subject of a nation that would later bring the killing blow to the Mexica Empire.[51]

The war between Mexico and Tlaxcala would eventually have devastating consequences, as the Tlaxcalans decided an alliance with Spain against Mexico on 23 September 1519 after a few battles proved that an alliance with this nation could help them destroy Moctezuma's reign.[104]

Contact with the Spanish

First interactions with the Spanish

In 1518,[24] Moctezuma received the first reports of Europeans landing on the east coast of his empire; this was the expedition of Juan de Grijalva who had landed on San Juan de Ulúa, which although within Totonac territory was under the auspices of the Aztec Empire. Moctezuma ordered that he be kept informed of any new sightings of foreigners at the coast and posted extra watchguards and watchtowers to accomplish this.[105]

When Cortés arrived in 1519, Moctezuma was immediately informed and he sent emissaries to meet the newcomers; one of them was an Aztec noble named Tentlil in the Nahuatl language but referred to in the writings of Cortés and Bernal Díaz del Castillo as "Tendile". As the Spaniards approached Tenochtitlán they allied with the Tlaxcalteca, who were enemies of the Aztec Triple Alliance, and they helped instigate revolt in many towns under Aztec dominion. Moctezuma was aware of this and sent gifts to the Spaniards, probably to show his superiority to the Spaniards and Tlaxcalteca.[106]

On 8 November 1519, Moctezuma met Cortés on the causeway leading into Tenochtitlán and the two leaders exchanged gifts. Moctezuma gave Cortés the gift of an Aztec calendar, one disc of crafted gold, and another of silver. Cortés later melted these down for their monetary value.[107]

According to Cortés, Moctezuma immediately volunteered to cede his entire realm to Charles V, King of Spain. Though some indigenous accounts written in the 1550s partly support this notion, it is still unbelievable for several reasons. As Aztec rulers spoke an overly polite language that needed a translation for their subjects to understand, it was difficult to determine what Moctezuma said. According to an indigenous account, he said to Cortés: "You have come to sit on your seat of authority, which I have kept for a while for you, where I have been in charge for you, for your agents the rulers ..." However, these words might be a polite expression that was meant to convey the exact opposite meaning, which was common in Nahua culture; Moctezuma might have intended these words to assert his stature and multigenerational legitimacy. Also, according to Spanish law, the king had no right to demand that foreign peoples become his subjects, but he had every right to bring rebels to heel. Therefore, to give the Spanish the necessary legitimacy to wage war against the indigenous people, Cortés might just have said what the Spanish king needed to hear.[108]

Host and prisoner of the Spaniards

Six days after their arrival, Moctezuma became a prisoner in his own house. Exactly why this happened is not clear from the extant sources.

According to the Spanish, the arrest was made as a result of an attack perpetrated by a tribute collector from Nautla named Qualpopoca (or Quetzalpopoca) on a Spanish Totonac garrison. The garrison was under the command of a Spanish captain named Juan de Escalante and the attack was in retaliation for the Totonac rebellion against Moctezuma which started in July 1519 after the Spanish arrived. This attack resulted in the death of many Totonacs and approximately seven Spaniards, including Escalante.[109] Though some Spaniards described that this was the only reason for Moctezuma's arrest, others have suspected that Escalante's death was merely used as an excuse by Cortés to imprison Moctezuma and usurp power over Mexico, positing that Cortés might have planned to imprison Moctezuma before they even met.[110] Cortés himself admitted that he imprisoned Moctezuma primarily to avoid losing control over Mexico, understanding that nearly all of his forces were within his domains.[111]

Moctezuma claimed innocence for this incident, claiming that though he was aware of the attack as Quetzalpopoca brought him the severed head of a Spaniard as a demonstration of his success, he never ordered it and was highly displeased by these events.[112]

Around 20 days after his arrest, Quetzalpopoca was captured, together with his son and 15 nobles who allegedly participated in the attack, and after a brief interrogation, he admitted that indeed Moctezuma was innocent. He was publicly executed by burning soon after, but Moctezuma remained prisoner regardless.[113]

Despite his imprisonment, Moctezuma continued to live a somewhat comfortable life, being free to perform many of his daily activities and being respected as a monarch. Cortés himself even ordered for any soldiers who disrespected him to be physically and roughly punished regardless of rank or position. However, despite still being treated as a respected monarch, he had virtually lost most of his power as emperor as the Spaniards oversaw nearly all of his activities.[114]

Moctezuma repeatedly protected the Spaniards against potential threats using the little power he had left, either under the threat of the Spanish or by his own will, such as during the succession crisis in Texcoco mentioned above, when he ordered for the ruler of Texcoco, Cacamatzin, to be arrested as he was planning to form an army to attack the Spaniards.

The Aztec nobility reportedly became increasingly displeased with the large Spanish army staying in Tenochtitlán, and Moctezuma told Cortés that it would be best if they left. Shortly thereafter, in April 1520, Cortés left to fight Pánfilo de Narváez, who had landed in Mexico to arrest Cortés. During his absence, tensions between Spaniards and Aztecs exploded into the Massacre in the Great Temple, and Moctezuma became a hostage used by the Spaniards to ensure their security.[N.B. 4]

Death

In the subsequent battles with the Spaniards after Cortés' return, Moctezuma was killed. The details of his death are unknown, with different versions of his demise given by different sources.

In his Historia, Bernal Díaz del Castillo states that on 29 June 1520, the Spanish forced Moctezuma to appear on the balcony of his palace, appealing to his countrymen to retreat. Four leaders of the Aztec army met with Moctezuma to talk, urging their countrymen to cease their constant firing upon the stronghold for a time. Díaz states: "Many of the Mexican Chieftains and Captains knew him well and at once ordered their people to be silent and not to discharge darts, stones or arrows, and four of them reached a spot where Montezuma [Moctezuma] could speak to them."[115]

Díaz alleges that the Aztecs informed Moctezuma that a relative of his had risen to the throne and ordered their attack to continue until all of the Spanish were annihilated, but expressed remorse at Moctezuma's captivity and stated that they intended to revere him even more if they could rescue him. Regardless of the earlier orders to hold fire, however, the discussion between Moctezuma and the Aztec leaders was immediately followed by an outbreak of violence. The Aztecs, disgusted by the actions of their leader, renounced Moctezuma and named his brother Cuitláhuac tlatoani in his place. To pacify his people, and undoubtedly pressured by the Spanish, Moctezuma spoke to a crowd but was struck dead by a rock.[116] Díaz gives this account:

They had hardly finished this speech when suddenly such a shower of stones and darts were discharged that (our men who were shielding him having neglected for a moment their duty because they saw how the attack ceased while he spoke to them) he was hit by three stones, one on the head, another on the arm and another on the leg, and although they begged him to have the wounds dressed and to take food, and spoke kind words to him about it, he would not. Indeed, when we least expected it, they came to say that he was dead.[117]

Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún oversaw the recording of two versions of the conquest of the Aztec Empire from the Tenochtitlán-Tlatelolco viewpoint. Book 12 of the Florentine Codex, which indigenous scholars composed under Sahagún's tutelage, is an illustrative, Spanish and Nahuatl account of the Conquest which attributes Moctezuma II's death to Spanish conquistadors. According to the Codex, the bodies of Moctezuma and Itzquauhtzin were cast out of the Palace by the Spanish; the body of Moctezuma was gathered up and cremated at Copulco.

And four days after they had been hurled from the [pyramid] temple, [the Spaniards] came to cast away [the bodies of] Moctezuma and Itzquauhtzin, who had died, at the water's edge at a place called Teoayoc. For at that place there was the image of a turtle carved of stone; the stone had an appearance like that of a turtle.[118]

History of the Indies of New Spain by Dominican friar Diego Durán references both Spanish and indigenous accounts of Moctezuma II's death. Durán notes that Spanish historians and the former conquistador he interviewed recall Moctezuma dying to Aztec projectiles. However, his indigenous text and a historical informant claimed that Cortés' forces stabbed Moctezuma to death.[119] In other indigenous annals, the Aztecs found Moctezuma strangled to death in his palace.[120]

Aftermath

The Spaniards were forced to flee the city and they took refuge in Tlaxcala and signed a treaty with the natives there to conquer Tenochtitlán, offering the Tlaxcalans control of Tenochtitlán and freedom from any kind of tribute.[citation needed]

Moctezuma was then succeeded by his brother Cuitláhuac, who died shortly afterwards during a smallpox epidemic. He was succeeded by his adolescent nephew, Cuauhtémoc. During the siege of the city, the sons of Moctezuma were murdered by the Aztecs, possibly because they wanted to surrender. By the following year, the Aztec Empire had fallen to an army of Spanish and their Native American allies, primarily Tlaxcalans, who were traditional enemies of the Aztecs.

Contemporary depictions

Bernal Díaz del Castillo

| Aztec civilization |

|---|

|

| Aztec society |

| Aztec history |

The firsthand account of Bernal Díaz del Castillo's True History of the Conquest of New Spain paints a portrait of a noble leader who struggles to maintain order in his kingdom after he is taken prisoner by Hernán Cortés. In his first description of Moctezuma, Díaz del Castillo writes:

The Great Montezuma was about forty years old, of good height, well proportioned, spare and slight, and not very dark, though of the usual Indian complexion. He did not wear his hair long but just over his ears, and he had a short black beard, well-shaped and thin. His face was rather long and cheerful, he had fine eyes, and in his appearance and manner could express geniality or, when necessary, a serious composure. He was very neat and clean and took a bath every afternoon. He had many women as his mistresses, the daughters of chieftains, but two legitimate wives who were Caciques[N.B. 5] in their own right, and only some of his servants knew of it. He was quite free from sodomy. The clothes he wore one day he did not wear again till three or four days later. He had a guard of two hundred chieftains lodged in rooms beside his own, only some of whom were permitted to speak to him.[121]

When Moctezuma was allegedly killed by being stoned to death by his people, "Cortés and all of us captains and soldiers wept for him, and there was no one among us that knew him and had dealings with him who did not mourn him as if he were our father, which was not surprising since he was so good. It was stated that he had reigned for seventeen years, and was the best king they ever had in Mexico, and that he had personally triumphed in three wars against countries he had subjugated. I have spoken of the sorrow we all felt when we saw that Montezuma was dead. We even blamed the Mercedarian friar for not having persuaded him to become a Christian."[122]

Hernán Cortés

Unlike Bernal Díaz, who was recording his memories many years after the fact, Cortés wrote his Cartas de relación (Letters from Mexico) to justify his actions to the Spanish Crown. His prose is characterized by simple descriptions and explanations, along with frequent personal addresses to the King. In his Second Letter, Cortés describes his first encounter with Moctezuma thus:

Moctezuma [sic] came to greet us and with him some two hundred lords, all barefoot and dressed in a different costume, but also very rich in their way and more so than the others. They came in two columns, pressed very close to the walls of the street, which is very wide and beautiful and so straight that you can see from one end to the other. Moctezuma came down the middle of this street with two chiefs, one on his right hand and the other on his left. And they were all dressed alike except that Moctezuma wore sandals whereas the others went barefoot, and they held his arm on either side.[123]

Anthony Pagden and Eulalia Guzmán have pointed out the Biblical messages that Cortés seems to ascribe to Moctezuma's retelling of the legend of Quetzalcoatl as a vengeful Messiah who would return to rule over the Mexica. Pagden has written that "There is no preconquest tradition which places Quetzalcoatl in this role, and it seems possible therefore that it was elaborated by Sahagún and Motolinía from informants who themselves had partially lost contact with their traditional tribal histories".[124][125]

Bernardino de Sahagún

The Florentine Codex, made by Bernardino de Sahagún and indigenous scholars under his tutelage, relied on native informants from Tlatelolco and generally portrays Tlatelolco and Tlatelolcan rulers in a favorable light relative to those of Tenochtitlan. Historian Matthew Restall claims that the Codex depicts Moctezuma as weak-willed, superstitious, and indulgent.[106] James Lockhart suggests that Moctezuma fills the role of a scapegoat for the Aztec defeat.[126]

Other historians have noted that the Codex may not necessarily cast Moctezuma as cowardly and responsible for Spanish colonization. Rebecca Dufendach argues that the Codex reflects the native informants' uniquely indigenous manner of portraying leaders who suffered from poor health brought on by fright.[127]

Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc

Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc, who may have written the Crónica Mexicayotl, was possibly a grandson of Moctezuma II. His chronicle may relate mostly to the genealogy of the Aztec rulers. He described Moctezuma's issue and estimated them to be nineteen – eleven sons and eight daughters.[128]

Depiction in early post-conquest literature

Some of the Aztec stories about Moctezuma describe him as being fearful of the Spanish newcomers, and some sources, such as the Florentine Codex, comment that the Aztecs believed the Spaniards to be gods and Cortés to be the returned god Quetzalcoatl. The veracity of this claim is difficult to ascertain, though some recent ethnohistorians specializing in early Spanish/Nahua relations have discarded it as post-conquest mythicalization.[129]

Much of the idea of Cortés being seen as a deity can be traced back to the Florentine Codex, written some 50 years after the conquest. In the codex's description of the first meeting between Moctezuma and Cortés, the Aztec ruler is described as giving a prepared speech in classical oratorical Nahuatl, a speech which as described verbatim in the codex (written by Sahagún's Tlatelolcan informants) included such prostrate declarations of divine or near-divine admiration as "You have graciously come on earth, you have graciously approached your water, your high place of Mexico, you have come down to your mat, your throne, which I have briefly kept for you, I who used to keep it for you", and, "You have graciously arrived, you have known pain, you have known weariness, now come on earth, take your rest, enter into your palace, rest your limbs; may our lords come on earth." While some historians such as Warren H. Carroll consider this as evidence that Moctezuma was at least open to the possibility that the Spaniards were divinely sent based on the Quetzalcoatl legend, others such as Matthew Restall argue that Moctezuma politely offered his throne to Cortés (if indeed he did ever give the speech as reported) may well have been meant as the exact opposite of what it was taken to mean, as politeness in Aztec culture was a way to assert dominance and show superiority.[130] Other parties have also propagated the idea that the Native Americans believed the conquistadors to be gods, most notably the historians of the Franciscan order such as Fray Gerónimo de Mendieta.[131] Bernardino de Sahagún, who compiled the Florentine Codex, was also a Franciscan priest.

Indigenous accounts of omens and Moctezuma's beliefs

Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590) includes in Book 12 of the Florentine Codex eight events said to have occurred before the arrival of the Spanish. These were purportedly interpreted as signs of a possible disaster, e.g. a comet, the burning of a temple, a crying ghostly woman, and others. Some speculate that the Aztecs were particularly susceptible to such ideas of doom and disaster because the particular year in which the Spanish arrived coincided with a "tying of years" ceremony at the end of a 52-year cycle in the Aztec calendar, which in Aztec belief was linked to changes, rebirth, and dangerous events. The belief of the Aztecs being rendered passive by their superstition is referred to by Matthew Restall as part of "The Myth of Native Desolation" to which he dedicates chapter 6 in his book Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest.[129] These legends are likely a part of the post-conquest rationalization by the Aztecs of their defeat, and serve to show Moctezuma as indecisive, vain, and superstitious, and ultimately the cause of the fall of the Aztec Empire.[126]

According to 16th-century Spanish historian Diego Durán, who was one of the most important chroniclers of the indigenous stories of the empire, Nezahualpilli was among those who informed Moctezuma of the imminent destruction of the empire by a foreign invader, warning him that omens confirming his fears will soon appear. This warning caused Moctezuma great fear and he made a series of erratic decisions immediately after, such as severe punishments against his soldiers for disappointing results after battles against the Tlaxcalans.[132]

Ethnohistorian Susan Gillespie has argued that the Nahua understanding of history as repeating itself in cycles also led to a subsequent rationalization of the events of the conquests. In this interpretation, the description of Moctezuma, the final ruler of the Aztec Empire before the Spanish conquest, was tailored to fit the role of earlier rulers of ending dynasties—for example, Quetzalcoatl, the mythical last ruler of the Toltecs.[133] In any case it is within the realm of possibility that the description of Moctezuma in post-conquest sources was coloured by his role as a monumental closing figure of Aztec history.[citation needed]

Personal life

Wives, concubines, and children

Moctezuma had numerous wives and concubines by whom he fathered an enormous family, but only two women held the position of queen – Tlapalizquixochtzin and Teotlalco. His partnership with Tlapalizquixochtzin, daughter of Matlaccoatzin of Ecatepec, also made him king consort of Ecatepec since she was queen of that city.[2] However, Spanish accounts describe that very few people in Mexico knew that these two women held such positions of power, some of those who knew being a few of his close servants.[52]

Of his many wives may be named the princesses Teitlalco, Acatlan, and Miahuaxochitl, of whom the first named appears to have been the only legitimate consort. By her, he left a son, Chimalpopoca, who fell during the Noche Triste,[134] and a daughter, Tecuichpoch, later baptized as Isabel Moctezuma. By the Princess Acatlan were left two daughters, baptized as Maria and Mariana (also known as Leonor);[135] the latter alone left offspring, from whom descends the Sotelo-Montezuma family.[136]

Though the exact number of his children is unknown and the names of most of them have been lost to history, according to a Spanish chronicler, by the time he was taken captive, Moctezuma had fathered 100 children and fifty of his wives and concubines were then in some stage of pregnancy, though this estimate may have been exaggerated.[137] As Aztec culture made class distinctions between the children of senior wives, lesser wives, and concubines, not all of his children were considered equal in nobility or inheritance rights. Among his many children were Princess Isabel Moctezuma, Princess Mariana Leonor Moctezuma,[135] and sons Chimalpopoca (not to be confused with the previous huey tlatoani) and Tlaltecatzin.[138] Noteworthy is also Francisca de Moctezuma, his daughter by Tlapalizquixochtzin, Queen-regant of Ecatepec. She married Don Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin, the first governor of Mexico City.

Activities

Moctezuma was physically fit and practised a variety of sports, among them archery and swimming. He was well-trained in the arts of war, as he was experienced on the battlefield from an early age.[139]

Among the sports he practised, he was an active hunter, and often used to hunt for deer, rabbits, and various birds in a certain section of a forest (likely the Bosque de Chapultepec) that was exclusive to him and whomever he invited. It was prohibited for anyone without permission to enter, and allegedly any trespassers would be put to death. He also used to invite servants to this forest, should he order for certain animals to be hunted for him, which would often be done for the entertainment of his guests.[140]

Moctezuma was recorded to have been heavily obsessed with cleanliness and personal hygiene, such as bathing multiple times a day in his private pool; as well as not wearing the same clothes every day.[52]

A Spanish soldier accompanying Hernan Cortés during the conquest of the Aztec Empire reported that when Moctezuma II dined, he took no other beverage than chocolate, served in a golden goblet. Moctezuma was passionate about chocolate; he had it flavoured with vanilla or other spices such as chili peppers, and his chocolate was whipped into a froth that dissolved in the mouth. No fewer than 60 portions each day reportedly may have been consumed by Moctezuma II, and 2,000 more by the nobles of his court.[141]

Legacy

Descendants in Mexico and the Spanish nobility

Several lines of descendants exist in Mexico and Spain through Moctezuma II's son and daughters, notably Tlacahuepan Ihualicahuaca, or Pedro Moctezuma, and Tecuichpoch Ixcaxochitzin, or Isabel Moctezuma. Following the conquest, Moctezuma's daughter, Techichpotzin (or Tecuichpoch), became known as Isabel Moctezuma and was given a large estate by Cortés, who also fathered a child by her, Leonor Cortés Moctezuma, who in turn was the mother of Isabel de Tolosa Cortés de Moctezuma.[142][143] Isabel married consecutively to Cuauhtémoc (the last Mexican sovereign), to a conquistador in Cortés' original group, Alonso Grado (died c. 1527), a poblador (a Spaniard who had arrived after the fall of Tenochtitlán), to Pedro Andrade Gallego (died c. 1531), and to conquistador Juan Cano de Saavedra, who survived her.[144] She had children by the latter two, from whom descend the illustrious families of Andrade-Montezuma and Cano-Montezuma. A nephew of Moctezuma II was Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin.