Mestranol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Enovid, Norinyl, Ortho-Novum, others |

| Other names | Ethinylestradiol 3-methyl ether; EEME; EE3ME; CB-8027; L-33355; RS-1044; 17α-Ethynylestradiol 3-methyl ether; 17α-Ethynyl-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol; 3-Methoxy-19-norpregna-1,3,5(10)-trien-20-yn-17β-ol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| MedlinePlus | a601050 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth[1] |

| Drug class | Estrogen; Estrogen ether |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolites | Ethinylestradiol |

| Elimination half-life | Mestranol: 50 min[2] EE: 7–36 hours[3][4][5][6] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.707 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H26O2 |

| Molar mass | 310.437 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Mestranol, sold under the brand names Enovid, Norinyl, and Ortho-Novum among others, is an estrogen medication which has been used in birth control pills, menopausal hormone therapy, and the treatment of menstrual disorders.[1][7][8][9] It is formulated in combination with a progestin and is not available alone.[9] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Side effects of mestranol include nausea, breast tension, edema, and breakthrough bleeding among others.[10] It is an estrogen, or an agonist of the estrogen receptors, the biological target of estrogens like estradiol.[11] Mestranol is a prodrug of ethinylestradiol in the body.[11]

Mestranol was discovered in 1956 and was introduced for medical use in 1957.[12][13] It was the estrogen component in the first birth control pill.[12][13] In 1969, mestranol was replaced by ethinylestradiol in most birth control pills, although mestranol continues to be used in a few birth control pills even today.[14][9] Mestranol remains available only in a few countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, and Chile.[9]

Medical uses

Mestranol was employed as the estrogen component in many of the first oral contraceptives, such as mestranol/noretynodrel (brand name Enovid) and mestranol/norethisterone (brand names Ortho-Novum, Norinyl), and is still in use today.[7][8][9] In addition to its use as an oral contraceptive, mestranol has been used as a component of menopausal hormone therapy for the treatment of menopausal symptoms.[1]

Side effects

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2023) |

Pharmacology

Mestranol is a biologically inactive prodrug of ethinylestradiol to which it is demethylated in the liver (via O-Dealkylation) with a conversion efficiency of 70% (50 μg of mestranol is pharmacokinetically bioequivalent to 35 μg of ethinylestradiol).[15][16][11] It has been found to possess 0.1 to 2.3% of the relative binding affinity of estradiol (100%) for the estrogen receptor, compared to 75 to 190% for ethinylestradiol.[17][18]

The elimination half-life of mestranol has been reported to be 50 minutes.[2] The elimination half-life of the active form of mestranol, ethinylestradiol, is 7 to 36 hours.[3][4][5][6]

The effective ovulation-inhibiting dosage of mestranol has been studied in women.[19][20][21] It has been reported to be about 98% effective at inhibiting ovulation at a dosage of 75 or 80 μg/day.[22][21][23] In another study, the ovulation rate was 15.4% at 50 μg/day, 5.7% at 80 μg/day, and 1.1% at 100 μg/day.[24]

| Estrogen | Other names | RBA (%)a | REP (%)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | ERα | ERβ | ||||

| Estradiol | E2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Estradiol 3-sulfate | E2S; E2-3S | ? | 0.02 | 0.04 | ||

| Estradiol 3-glucuronide | E2-3G | ? | 0.02 | 0.09 | ||

| Estradiol 17β-glucuronide | E2-17G | ? | 0.002 | 0.0002 | ||

| Estradiol benzoate | EB; Estradiol 3-benzoate | 10 | 1.1 | 0.52 | ||

| Estradiol 17β-acetate | E2-17A | 31–45 | 24 | ? | ||

| Estradiol diacetate | EDA; Estradiol 3,17β-diacetate | ? | 0.79 | ? | ||

| Estradiol propionate | EP; Estradiol 17β-propionate | 19–26 | 2.6 | ? | ||

| Estradiol valerate | EV; Estradiol 17β-valerate | 2–11 | 0.04–21 | ? | ||

| Estradiol cypionate | EC; Estradiol 17β-cypionate | ?c | 4.0 | ? | ||

| Estradiol palmitate | Estradiol 17β-palmitate | 0 | ? | ? | ||

| Estradiol stearate | Estradiol 17β-stearate | 0 | ? | ? | ||

| Estrone | E1; 17-Ketoestradiol | 11 | 5.3–38 | 14 | ||

| Estrone sulfate | E1S; Estrone 3-sulfate | 2 | 0.004 | 0.002 | ||

| Estrone glucuronide | E1G; Estrone 3-glucuronide | ? | <0.001 | 0.0006 | ||

| Ethinylestradiol | EE; 17α-Ethynylestradiol | 100 | 17–150 | 129 | ||

| Mestranol | EE 3-methyl ether | 1 | 1.3–8.2 | 0.16 | ||

| Quinestrol | EE 3-cyclopentyl ether | ? | 0.37 | ? | ||

| Footnotes: a = Relative binding affinities (RBAs) were determined via in-vitro displacement of labeled estradiol from estrogen receptors (ERs) generally of rodent uterine cytosol. Estrogen esters are variably hydrolyzed into estrogens in these systems (shorter ester chain length -> greater rate of hydrolysis) and the ER RBAs of the esters decrease strongly when hydrolysis is prevented. b = Relative estrogenic potencies (REPs) were calculated from half-maximal effective concentrations (EC50) that were determined via in-vitro β‐galactosidase (β-gal) and green fluorescent protein (GFP) production assays in yeast expressing human ERα and human ERβ. Both mammalian cells and yeast have the capacity to hydrolyze estrogen esters. c = The affinities of estradiol cypionate for the ERs are similar to those of estradiol valerate and estradiol benzoate (figure). Sources: See template page. | ||||||

| Compound | Dosage for specific uses (mg usually)[a] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETD[b] | EPD[b] | MSD[b] | MSD[c] | OID[c] | TSD[c] | ||

| Estradiol (non-micronized) | 30 | ≥120–300 | 120 | 6 | - | - | |

| Estradiol (micronized) | 6–12 | 60–80 | 14–42 | 1–2 | >5 | >8 | |

| Estradiol valerate | 6–12 | 60–80 | 14–42 | 1–2 | - | >8 | |

| Estradiol benzoate | - | 60–140 | - | - | - | - | |

| Estriol | ≥20 | 120–150[d] | 28–126 | 1–6 | >5 | - | |

| Estriol succinate | - | 140–150[d] | 28–126 | 2–6 | - | - | |

| Estrone sulfate | 12 | 60 | 42 | 2 | - | - | |

| Conjugated estrogens | 5–12 | 60–80 | 8.4–25 | 0.625–1.25 | >3.75 | 7.5 | |

| Ethinylestradiol | 200 μg | 1–2 | 280 μg | 20–40 μg | 100 μg | 100 μg | |

| Mestranol | 300 μg | 1.5–3.0 | 300–600 μg | 25–30 μg | >80 μg | - | |

| Quinestrol | 300 μg | 2–4 | 500 μg | 25–50 μg | - | - | |

| Methylestradiol | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | |

| Diethylstilbestrol | 2.5 | 20–30 | 11 | 0.5–2.0 | >5 | 3 | |

| DES dipropionate | - | 15–30 | - | - | - | - | |

| Dienestrol | 5 | 30–40 | 42 | 0.5–4.0 | - | - | |

| Dienestrol diacetate | 3–5 | 30–60 | - | - | - | - | |

| Hexestrol | - | 70–110 | - | - | - | - | |

| Chlorotrianisene | - | >100 | - | - | >48 | - | |

| Methallenestril | - | 400 | - | - | - | - | |

Chemistry

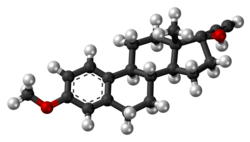

Mestranol, also known as ethinylestradiol 3-methyl ether (EEME) or as 17α-ethynyl-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol, is a synthetic estrane steroid and a derivative of estradiol.[44][45][46] It is specifically a derivative of ethinylestradiol (17α-ethynylestradiol) with a methyl ether at the C3 position.[44][45]

History

In April 1956, noretynodrel was investigated, in Puerto Rico, in the first large-scale clinical trial of a progestogen as an oral contraceptive.[12][13] The trial was conducted in Puerto Rico due to the high birth rate in the country and concerns of moral censure in the United States.[47] It was discovered early into the study that the initial chemical syntheses of noretynodrel had been contaminated with small amounts (1–2%) of the 3-methyl ether of ethinylestradiol (noretynodrel having been synthesized from ethinylestradiol).[12][13] When this impurity was removed, higher rates of breakthrough bleeding occurred.[12][13] As a result, mestranol, that same year (1956),[48] was developed and serendipitously identified as a very potent synthetic estrogen (and eventually as a prodrug of ethinylestradiol), given its name, and added back to the formulation.[12][13] This resulted in Enovid by G. D. Searle & Company, the first oral contraceptive and a combination of 9.85 mg noretynodrel and 150 μg mestranol per pill.[12][13]

Around 1969, mestranol was replaced by ethinylestradiol in most combined oral contraceptives due to widespread panic about the recently uncovered increased risk of venous thromboembolism with estrogen-containing oral contraceptives.[14] The rationale was that ethinylestradiol was approximately twice as potent by weight as mestranol and hence that the dose could be halved, which it was thought might result in a lower incidence of venous thromboembolism.[14] Whether this actually did result in a lower incidence of venous thromboembolism has never been assessed.[14]

Society and culture

Generic names

Mestranol is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, USP, BAN, DCF, and JAN, while mestranolo is its DCIT.[44][45][1][9]

Brand names

Mestranol has been marketed under a variety of brand names, mostly or exclusively in combination with progestins, including Devocin, Enavid, Enovid, Femigen, Mestranol, Norbiogest, Ortho-Novin, Ortho-Novum, Ovastol, and Tranel among others.[7][44][49][45] Today, it continues to be sold in combination with progestins under brand names including Lutedion, Necon, Norinyl, Ortho-Novum, and Sophia.[9]

Availability

Mestranol remains available only in the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Chile.[9] It is only marketed in combination with progestins, such as norethisterone.[9]

Research

Mestranol has been studied as a male contraceptive and was found to be highly effective.[50][51][52][53] At a dosage of 0.45 mg/day, it suppressed gonadotropin levels, reduced sperm count to zero within 4 to 6 weeks, and decreased libido, erectile function, and testicular size.[50][51][53][52] Gynecomastia occurred in all of the men.[50][51][53][52] These findings contributed to the conclusion that estrogens would be unacceptable as contraceptives for men.[51]

Environmental presence

In 2021, mestranol was one of the 12 compounds identified in sludge samples taken from 12 wastewater treatment plants in California that were collectively associated with estrogenic activity in in vitro. [54]

References

- ^ a b c d e Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- ^ a b Runnebaum B, Rabe T (17 April 2013). Gynäkologische Endokrinologie und Fortpflanzungsmedizin: Band 1: Gynäkologische Endokrinologie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-3-662-07635-4.

- ^ a b Hughes CL, Waters MD (23 March 2016). Translational Toxicology: Defining a New Therapeutic Discipline. Humana Press. pp. 73–. ISBN 978-3-319-27449-2.

- ^ a b Goldzieher JW, Brody SA (December 1990). "Pharmacokinetics of ethinyl estradiol and mestranol". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 163 (6 Pt 2): 2114–2119. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(90)90550-Q. PMID 2256522.

- ^ a b Stanczyk FZ, Archer DF, Bhavnani BR (June 2013). "Ethinyl estradiol and 17β-estradiol in combined oral contraceptives: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and risk assessment". Contraception. 87 (6): 706–727. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.12.011. PMID 23375353.

- ^ a b Shellenberger TE (1986). "Pharmacology of estrogens". The Climacteric in Perspective. Springer. pp. 393–410. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-4145-8_36. ISBN 978-94-010-8339-3.

- ^ a b c Marks L (2010). Sexual Chemistry: A History of the Contraceptive Pill. Yale University Press. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-0-300-16791-7.

- ^ a b Blum RW (22 October 2013). Adolescent Health Care: Clinical Issues. Elsevier Science. pp. 216–. ISBN 978-1-4832-7738-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Mestranol and norethindrone Uses, Side Effects & Warnings". Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-24.

- ^ Wittlinger H (1980). "Clinical Effects of Estrogens". Functional Morphologic Changes in Female Sex Organs Induced by Exogenous Hormones. Springer. pp. 67–71. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-67568-3_10. ISBN 978-3-642-67570-6.

- ^ a b c Shoupe D (7 November 2007). The Handbook of Contraception: A Guide for Practical Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-59745-150-5.

EE is about 1.7 times as potent as the same weight of mestranol.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sneader W (23 June 2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 202–. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, Katz VL (2012). Comprehensive Gynecology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1.

- ^ a b c d Aronson JK (21 February 2009). Meyler's Side Effects of Endocrine and Metabolic Drugs. Elsevier. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-0-08-093292-7.

- ^ Faigle JW, Schenkel L (1998). "Pharmacokinetics of estrogens and progestogens". In Fraser IS, Whitehead MI, Jansen R, Lobo RA (eds.). Estrogens and Progestogens in Clinical Practice. London: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 273–294. ISBN 0-443-04706-5.

- ^ Falcone T, Hurd WW (2007). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 388–. ISBN 978-0-323-03309-1.

- ^ Blair RM, Fang H, Branham WS, Hass BS, Dial SL, Moland CL, et al. (March 2000). "The estrogen receptor relative binding affinities of 188 natural and xenochemicals: structural diversity of ligands". Toxicological Sciences. 54 (1): 138–153. doi:10.1093/toxsci/54.1.138. PMID 10746941.

- ^ Ruenitz PC (2010). "Female Sex Hormones, Contraceptives, And Fertility Drugs". Burger's Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery. Wiley. pp. 219–264. doi:10.1002/0471266949.bmc054. ISBN 978-0-471-26694-5.

- ^ Bingel AS, Benoit PS (February 1973). "Oral contraceptives: therapeutics versus adverse reactions, with an outlook for the future I". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 62 (2): 179–200. doi:10.1002/jps.2600620202. PMID 4568621.

- ^ Pincus G (3 September 2013). The Control of Fertility. Elsevier. pp. 222–. ISBN 978-1-4832-7088-3.

- ^ a b Martinez-Manautou J, Rudel HW (1966). "Antiovulatory Activity of Several Synthetic and Natural Estrogens". In Greenblatt BR (ed.). Ovulation: Stimulation, Suppression, and Detection. Lippincott. pp. 243–253. ISBN 978-0-397-59010-0.

- ^ Elger W (1972). "Physiology and pharmacology of female reproduction under the aspect of fertility control". Reviews of Physiology Biochemistry and Experimental Pharmacology, Volume 67. Ergebnisse der Physiologie Reviews of Physiology. Vol. 67. pp. 69–168. doi:10.1007/BFb0036328. ISBN 3-540-05959-8. PMID 4574573.

- ^ Herr F, Revesz C, Manson AJ, Jewell JB (1970). "Biological Properties of Estrogen Sulfates". Chemical and Biological Aspects of Steroid Conjugation. Springer. pp. 368–408. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-49793-3_8 (inactive 2024-11-02). ISBN 978-3-642-49506-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Goldzieher JW, Pena A, Chenault CB, Woutersz TB (July 1975). "Comparative studies of the ethynyl estrogens used in oral contraceptives. II. Antiovulatory potency". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 122 (5): 619–624. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(75)90061-7. PMID 1146927.

- ^ Lauritzen C (September 1990). "Clinical use of oestrogens and progestogens". Maturitas. 12 (3): 199–214. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(90)90004-P. PMID 2215269.

- ^ Lauritzen C (June 1977). "[Estrogen thearpy in practice. 3. Estrogen preparations and combination preparations]" [Estrogen therapy in practice. 3. Estrogen preparations and combination preparations]. Fortschritte Der Medizin (in German). 95 (21): 1388–92. PMID 559617.

- ^ Wolf AS, Schneider HP (12 March 2013). Östrogene in Diagnostik und Therapie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-3-642-75101-1.

- ^ Göretzlehner G, Lauritzen C, Römer T, Rossmanith W (1 January 2012). Praktische Hormontherapie in der Gynäkologie. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-3-11-024568-4.

- ^ Knörr K, Beller FK, Lauritzen C (17 April 2013). Lehrbuch der Gynäkologie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-3-662-00942-0.

- ^ Horský J, Presl J (1981). "Hormonal Treatment of Disorders of the Menstrual Cycle". In Horsky J, Presl J (eds.). Ovarian Function and its Disorders: Diagnosis and Therapy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 309–332. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-8195-9_11. ISBN 978-94-009-8195-9.

- ^ Pschyrembel W (1968). Praktische Gynäkologie: für Studierende und Ärzte. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 598–599. ISBN 978-3-11-150424-7.

- ^ Lauritzen CH (January 1976). "The female climacteric syndrome: significance, problems, treatment". Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica. Supplement. 51: 47–61. doi:10.3109/00016347509156433. PMID 779393.

- ^ Lauritzen C (1975). "The Female Climacteric Syndrome: Significance, Problems, Treatment". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 54 (s51): 48–61. doi:10.3109/00016347509156433. ISSN 0001-6349.

- ^ Kopera H (1991). "Hormone der Gonaden". Hormonelle Therapie für die Frau. Kliniktaschenbücher. pp. 59–124. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-95670-6_6. ISBN 978-3-540-54554-5. ISSN 0172-777X.

- ^ Scott WW, Menon M, Walsh PC (April 1980). "Hormonal Therapy of Prostatic Cancer". Cancer. 45 (Suppl 7): 1929–1936. doi:10.1002/cncr.1980.45.s7.1929. PMID 29603164.

- ^ Leinung MC, Feustel PJ, Joseph J (2018). "Hormonal Treatment of Transgender Women with Oral Estradiol". Transgender Health. 3 (1): 74–81. doi:10.1089/trgh.2017.0035. PMC 5944393. PMID 29756046.

- ^ Ryden AB (1950). "Natural and synthetic oestrogenic substances; their relative effectiveness when administered orally". Acta Endocrinologica. 4 (2): 121–39. doi:10.1530/acta.0.0040121. PMID 15432047.

- ^ Ryden AB (1951). "The effectiveness of natural and synthetic oestrogenic substances in women". Acta Endocrinologica. 8 (2): 175–91. doi:10.1530/acta.0.0080175. PMID 14902290.

- ^ Kottmeier HL (1947). "Ueber blutungen in der menopause: Speziell der klinischen bedeutung eines endometriums mit zeichen hormonaler beeinflussung: Part I". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 27 (s6): 1–121. doi:10.3109/00016344709154486. ISSN 0001-6349.

There is no doubt that the conversion of the endometrium with injections of both synthetic and native estrogenic hormone preparations succeeds, but the opinion whether native, orally administered preparations can produce a proliferation mucosa changes with different authors. PEDERSEN-BJERGAARD (1939) was able to show that 90% of the folliculin taken up in the blood of the vena portae is inactivated in the liver. Neither KAUFMANN (1933, 1935), RAUSCHER (1939, 1942) nor HERRNBERGER (1941) succeeded in bringing a castration endometrium into proliferation using large doses of orally administered preparations of estrone or estradiol. Other results are reported by NEUSTAEDTER (1939), LAUTERWEIN (1940) and FERIN (1941); they succeeded in converting an atrophic castration endometrium into an unambiguous proliferation mucosa with 120–300 oestradiol or with 380 oestrone.

- ^ Rietbrock N, Staib AH, Loew D (11 March 2013). Klinische Pharmakologie: Arzneitherapie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 426–. ISBN 978-3-642-57636-2.

- ^ Martinez-Manautou J, Rudel HW (1966). "Antiovulatory Activity of Several Synthetic and Natural Estrogens". In Robert Benjamin Greenblatt (ed.). Ovulation: Stimulation, Suppression, and Detection. Lippincott. pp. 243–253.

- ^ Herr F, Revesz C, Manson AJ, Jewell JB (1970). "Biological Properties of Estrogen Sulfates". Chemical and Biological Aspects of Steroid Conjugation. pp. 368–408. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-49793-3_8. ISBN 978-3-642-49506-9.

- ^ Duncan CJ, Kistner RW, Mansell H (October 1956). "Suppression of ovulation by trip-anisyl chloroethylene (TACE)". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 8 (4): 399–407. PMID 13370006.

- ^ a b c d Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 775–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ a b c d Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 656–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ Labhart A (6 December 2012). Clinical Endocrinology: Theory and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 575–. ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

- ^ Filshie M, Guillebaud J (22 October 2013). Contraception: Science and Practice. Elsevier Science. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-1-4831-6366-6.

- ^ Billingsley FS (February 1969). "Lactation suppression utilizing norethynodrel with mestranol". The Journal of the Florida Medical Association. 56 (2): 95–97. PMID 4884828.

- ^ Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Elsevier. 22 October 2013. pp. 2109–. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3.

- ^ a b c Dorfman RI (1980). "Pharmacology of estrogens-general". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 9 (1): 107–119. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(80)90018-2. PMID 6771777.

- ^ a b c d Jackson H (November 1975). "Progress towards a male oral contraceptive". Clinics in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 4 (3): 643–663. doi:10.1016/S0300-595X(75)80051-X. PMID 776453.

- ^ a b c Oettel M (1999). "Estrogens and Antiestrogens in the Male". In Oettel M, Schillinger E (eds.). Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 135 / 2. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 505–571. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-60107-1_25. ISBN 978-3-642-60107-1. ISSN 0171-2004.

- ^ a b c Heller CG, Moore DJ, Paulsen CA, Nelson WO, Laidlaw WM (December 1959). "Effects of progesterone and synthetic progestins on the reproductive physiology of normal men". Federation Proceedings. 18: 1057–1065. PMID 14400846.

- ^ Black GP, He G, Denison MS, Young TM (May 2021). "Using Estrogenic Activity and Nontargeted Chemical Analysis to Identify Contaminants in Sewage Sludge". Environmental Science & Technology. 55 (10): 6729–6739. Bibcode:2021EnST...55.6729B. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c07846. PMC 8378343. PMID 33909413.

- CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024

- CS1 German-language sources (de)

- CS1: long volume value

- Articles with short description

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Drugs not assigned an ATC code

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- Articles to be expanded from December 2023

- All articles to be expanded

- Articles with empty sections from December 2023

- All articles with empty sections

- Ethynyl compounds

- Estranes

- Estrogen ethers

- Hormonal contraception

- Prodrugs

- Synthetic estrogens