Merian C. Cooper

Merian C. Cooper | |

|---|---|

Merian C. Cooper in 1927 | |

| Born | Merian Caldwell Cooper October 24, 1893 Jacksonville, Florida, U.S. |

| Died | April 21, 1973 (aged 79) San Diego, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupations | |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Brigadier General (US) Podpułkownik (PL) |

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | |

Merian Caldwell Cooper (October 24, 1893 – April 21, 1973) was an American filmmaker, actor, and producer, as well as a former aviator who served as an officer in the United States Army Air Service and Polish Air Force. In film, his most famous work was the 1933 movie King Kong, and he is credited as co-inventor of the Cinerama film projection process. He was awarded an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement in 1952 and received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960. Before entering the movie business, Cooper had a distinguished career as the founder of the Kościuszko Squadron during the Polish–Soviet War and was a Soviet prisoner of war for a time. He got his start in film as part of the Explorers Club, traveling the world and documenting adventures. He was a member of the board of directors of Pan American Airways, but his love of film took priority. During his film career, he worked for companies such as Pioneer Pictures, RKO Pictures, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. In 1925, he and Ernest B. Schoedsack went to Iran and made Grass: A Nation's Battle for Life, a documentary about the Bakhtiari people.

Early life

Merian Caldwell Cooper was born in Jacksonville, Florida, to lawyer John C. Cooper and Mary Caldwell.[1] He was the youngest of three children. At age six, Cooper decided that he wanted to be an explorer after hearing stories from the book Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa.[2]: 10, 14 He was educated at The Lawrenceville School in New Jersey and graduated in 1911.[2]: 19 [3]

After graduation, Cooper received a prestigious appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy,[2]: 19 but was expelled during his senior year for "hell raising and for championing air power".[4] In 1916, Cooper worked for the Minneapolis Daily News as a reporter, where he met Delos Lovelace.[5] In the next few years, he also worked at the Des Moines Register-Leader and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.[2]: 22

Early military service

Georgia National Guard

In 1916, Cooper joined the Georgia National Guard to help chase Pancho Villa in Mexico.[6] He was called home in March 1917. He worked for the El Paso Herald on a 30-day leave of absence. After returning to his service, Cooper was appointed lieutenant; however, he refused the appointment hoping to participate in combat. Instead, he went to the Military Aeronautics School in Atlanta to learn to fly. Cooper graduated at the top of his class.[2]: 24–25

World War I

In October 1917, six months after the American entry into World War I, Cooper went to France with the 201st Squadron. He attended flying school in Issoudun. While flying with his friend, Cooper hit his head and was knocked out during a 200-foot plunge. After the incident, Cooper suffered from shock and had to relearn how to fly. Cooper requested to go to Clermont-Ferrand to be trained as a bomber pilot. He became a pilot with the 20th Aero Squadron (which later became the 1st Day Bombardment Group).[2]: 26–27

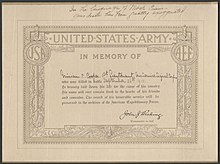

Cooper served as a DH-4 bomber pilot with the United States Army Air Service during World War I.[7] On September 26, 1918, his plane was shot down. The plane caught fire, and Cooper spun the plane to suck the flames out. Cooper survived, although he suffered burns, injured his hands, and was presumed dead. German soldiers saw his plane landing and took him to a prisoner reserve hospital.[2]: 8, 38–41 The death certificate on this page was sent to Cooper's family. The Army had believed him killed but he was captured by the Germans and taken as a Prisoner of war (POW). Cooper's father received a letter from Merian around the time the death certificate arrived. Merian C. Cooper sent the copy back to the Army with the notation on top "In the language of Mark Twain Your death has been greatly exaggerated."[8]

Captain Cooper remained in the Air Service after the war; he helped with Herbert Hoover's U.S. Food Administration that provided aid to Poland. He later became the chief of the Poland division.[9]

Kościuszko Squadron

From late 1919 until the 1921 Treaty of Riga, Cooper was a member of a volunteer American flight squadron, the Kościuszko Squadron, which supported the Polish Army in the Polish-Soviet War.[6] On July 13, 1920, his plane was shot down, and he spent nearly nine months in a Soviet prisoner of war camp[9] where the writer Isaac Babel interviewed him.[10] He escaped just before the war was over and made it to Latvia. For his valor he was decorated by Polish commander-in-chief Józef Piłsudski with the highest Polish military decoration, the Virtuti Militari.[9]

During his time as a POW, Cooper wrote an autobiography: Things Men Die For.[6] The manuscript was published by G. P. Putnam's Sons in New York (the Knickerbocker Press) in 1927. However, in 1928, Cooper regretted releasing certain details about "Nina" (probably Małgorzata Słomczyńska) with whom he had relations outside of wedlock. Cooper asked Dagmar Matson, who had the manuscript, to buy all the copies of the book possible. Matson found almost all 5,000 copies that had been printed. The books were destroyed, while Cooper and Matson each kept a copy.[6][11]

An interbellum Polish film directed by Leonard Buczkowski, Gwiaździsta eskadra (The Starry Squadron), was inspired by Cooper's experiences as a Polish Air Force officer. The film was made with the cooperation of the Polish army and was the most expensive Polish film prior to World War II. After World War II, all copies of the film found in Poland were destroyed by the Soviets.[12]

Career

Cooper and Schoedsack

After returning from overseas in 1921, Cooper got a job working the night shift at The New York Times. He was commissioned to write articles for Asia magazine. Cooper was able to travel with Ernest Schoedsack on a sea voyage on the Wisdom II. As part of the journey, he traveled to Abyssinia, or the Ethiopian Empire, where he met their prince regent, Ras Tefari, later known as Emperor Haile Selassie I. The ship left Abyssinia in February 1923. On their way home, the crew narrowly missed being attacked by pirates, and the ship was burned down.[2]: 81–83, 95–104 His three-part series for Asia was published in 1923.[2]: 106

After returning home, Cooper researched for the American Geographical Society. In 1924, Cooper joined Schoedsack and Marguerite Harrison who had embarked on an expedition that would be turned into the film Grass (1925).[2]: 111 They returned later the same year. Cooper became a member of the Explorers Club of New York in January 1925 and was asked to give lectures and attend events due to his extensive traveling. Grass was acquired by Paramount Pictures. Cooper and Schoedsack's first film gained the attention of Jesse Lasky, who commissioned the duo for their second film, Chang (1927). They also produced the film The Four Feathers,[2]: 132–137, 162 which was filmed among the fighting tribes of the Sudan. These films combined real footage with staged sequences.[7]

Pan American Airways

Between 1926 and 1927, Cooper discussed with John Hambleton the plans for Pan American Airways, which was formed during 1927.[2]: 180 Cooper was a member of the board of directors of Pan American Airways.[13] During his tenure at Pan Am, the company established the first regularly scheduled transatlantic service.[9] While he was on the board, Cooper did not devote his full attention to the organization; he took time in 1929 and 1930 to work on the script for King Kong. By 1931, he was back in Hollywood.[2]: 182, 183 He resigned from the board of directors in 1935, following health complications.[2]: 258

King Kong

Cooper said that he thought of King Kong after he had a dream that a giant gorilla was terrorizing New York City. When he awoke, he recorded the idea and used it for the film.[14] He was going to have a giant gorilla fight a Komodo dragon or other animal, but found that the technique of interlacing that he wanted to use would not provide realistic results.[2]: 194

Cooper needed a production studio for the film, but recognized the great cost of the movie, especially during the Great Depression. Cooper helped David Selznick get a job at RKO Pictures, which was struggling financially. Selznick became the vice president of RKO and asked Cooper to join him in September 1931, although he had only produced three films thus far in his career.[2]: 202–203 Cooper began working as an executive assistant at age thirty-eight.[15]: 74 He officially pitched the idea for King Kong in December 1931. Shortly after, he began to seek actors and build full-scale sets, although the screenplay was not yet complete.[2]: 207–208

The screenplay was delivered to Cooper in January 1932. Schoedsack contributed to the film, focusing on shooting scenes for the boat sequences and in native villages, leaving Cooper to shoot the jungle scenes. In February 1933, the title for the film was registered for copyright.[2]: 218–223 Throughout filming there were creative battles. Critics at RKO argued that the film should begin with Kong. Cooper believed that a film should begin with a "slow dramatic buildup that would establish everything from characters to mood ..." so that the action of the film could "naturally, relentlessly, roll on out of its own creative movement", and thus chose to not begin the film with a shot of Kong. The iconic scene in which Kong is atop of the Empire State Building was almost canceled by Cooper for legal reasons, but was kept in the film because RKO bought the rights to The Lost World.[2]: 229, 231

Overlapping with the production of King Kong was the making of The Most Dangerous Game, which began in May 1932. Cooper once again worked with Schoedsack to produce the film.[2]: 214

In the 1933 version of King Kong, Cooper and co-director Ernest B. Schoedsack appear at the end, piloting the plane that finally finishes off Kong. Cooper had reportedly said, "We should kill the sonofabitch ourselves."[16] Cooper personally cut a scene in King Kong in which four sailors are shaken off a rope bridge by Kong, fall into a ravine, and are eaten alive by giant spiders. According to Hollywood folklore, the decision was made after previews in January 1933, during which audience members either fled the theater in terror or talked about the ghastly scene throughout the remainder of the movie. However, more objective sources maintain that the scene merely slowed the film's pace. Despite the rumor that Cooper kept a print of the cut footage as a memento, it has never been found.[17] In 2021, film historian Ray Morton stated in an interview that, after looking through the films shooting schedule, he found no evidence the sequence was ever filmed.[18] In 1963, Cooper argued unsuccessfully that he should own the rights to King Kong; later in 1976, judges ruled that Cooper's estate owned the rights to King Kong outside the movie and its sequel.[2]: 362, 387 Selznick left RKO before the release of King Kong, and Cooper served as production chief from 1933 to 1934 with Pan Berman as his executive assistant.[15]

In the 2005 remake of King Kong, upon learning that Fay Wray was not available because she was making a film at RKO, Carl Denham (Jack Black) replies, "Cooper, huh? I might have known."[19]

Pioneer Pictures, Selznick International Pictures, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Cooper helped the Whitney cousins form Pioneer Pictures in 1933, while he was still working for RKO.[2]: 254 He was named vice president in charge of production for Pioneer Pictures in 1934.[20] He would use Pioneer Pictures to test his technicolor innovations. The company contracted with RKO in order to fulfill Cooper's obligations to the company, including She and The Last Days of Pompeii. Cooper later referred to She as the "worst picture I ever made."[2]: 259, 263

After these disappointments, Pioneer Pictures released a short film in three-strip technicolor called La Cucaracha, which was well-received. The film won an Academy Award in 1934. Pioneer released the first full-length technicolor film, Becky Sharp in 1935.[2]: 267–269 Cooper helped to advocate and pave the way for the ground-breaking technology of technicolor,[9] as well as the widescreen process called Cinerama.[21]

Selznick formed Selznick International Pictures in 1935, and Pioneer Pictures merged with it in June 1936.[2]: 269, 274 Cooper became the vice president of Selznick International Pictures that same year.[1] Cooper did not stay long; he resigned in 1937 due to disagreements over the film Stagecoach.[2]: 275

After resigning from Selznick International, Cooper went to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) in June 1937. A noteworthy project that Cooper was involved in was the fantasy film War Eagles. The film, which would have used extensive special effects, was abandoned in approximately 1939 and never finished. Cooper was to return to the Army Air Force.[2]: 276–281

World War II

Cooper re-enlisted and was commissioned a colonel in the U.S. Army Air Forces.[9][22] He served with Col. Robert L. Scott in India. He worked as logistics liaison for the Doolittle Raid. Thereafter, Cooper and Scott worked with Col. Caleb V. Haynes at Dinjan Airfield. They all were involved in establishing the Assam-Burma-China Ferrying Command. This marked the beginnings of The Hump Airlift.

Colonel Cooper later served in China as chief of staff for General Claire Chennault of the China Air Task Force, which was the precursor of the Fourteenth Air Force.[22] On October 25, 1942, a CATF raid consisting of 12 B-25s and 7 P-40s, led by Colonel Cooper, successfully bombed the Kowloon Docks at Hong Kong.[23]

He served from 1943 to 1945 in the Southwest Pacific as chief of staff for the Fifth Air Force's Bomber Command.[24] At the end of the war, he was promoted to brigadier general. For his contributions, he was also aboard the USS Missouri to witness Japan's surrender.[9]

Argosy Pictures and Cinerama

Cooper and his friend and frequent collaborator, noted director John Ford, formed Argosy Productions in 1946[25] and produced such notable films such as Wagon Master (1950),[26]: 112 Ford's Fort Apache (1948), and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949).[25] Cooper's films at Argosy reflected his patriotism and his vision of the United States.[2]: 321

Argosy negotiated a contract with RKO in 1946 to make four pictures. Cooper was able to make Grass a complete picture. Cooper also produced and directed Mighty Joe Young, which recruited Schoedsack as director. Cooper visited the set of the film every day to check on progress.[2]: 335, 340–342

Cooper left Argosy Pictures to pursue the process of Cinerama.[2]: 350 He became the vice president of Cinerama Productions in the 1950s and was also elected a board member. After failing to convince other board members to finance skilled technicians, Cooper left Cinerama with Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney to form C. V. Whitney Productions. Cooper continued to outline movies to be shot in Cinerama, but C. V. Whitney Productions only produced a few films.[2]: 355–358 Cooper was the executive producer for Ford's The Searchers (1956).[26]: 117

Awards

For his military service in Poland, Cooper was awarded the Silver Cross of the Order of Virtuti Militari (presented by Piłsudski), and Poland's Cross of Valour.[6]

In 1927, Cooper was one of 19 prominent Americans who were given the title of "Honorary Scouts" by the Boy Scouts of America for "... achievements in outdoor activity, exploration and worthwhile adventure ... of such an exceptional character as to capture the imagination of boys". The other honorees were Roy Chapman Andrews, Robert Bartlett, Frederick Russell Burnham, Richard E. Byrd, George Kruck Cherrie, James L. Clark, Lincoln Ellsworth, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, George Bird Grinnell, Charles Lindbergh, Donald Baxter MacMillan, Clifford H. Pope, George Palmer Putnam, Kermit Roosevelt, Carl Rungius, Stewart Edward White, and Orville Wright.[27]

In 1949, Mighty Joe Young won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, which was presented to Willis O'Brien, the man responsible for the film's special effects.[28][29]

Cooper was awarded an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement in 1952.[30] His film The Quiet Man was nominated for Best Picture that year, but lost to Cecil B. DeMille's The Greatest Show on Earth.[31] Cooper has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, though his first name is misspelled "Meriam".[32]

Personal life

Cooper was the father of Polish translator and writer Maciej Słomczyński.[6] He married film actress Dorothy Jordan on May 27, 1933.[1] They kept their marriage a secret from Hollywood for a month before it was reported by journalists. He suffered a heart attack later that year.[2]: 252, 255 In the 1950s, he supported Joseph McCarthy in his crusade to root out Communists in Hollywood and Washington, D.C.[33]

Cooper supported Barry Goldwater in the 1964 United States presidential election.[34]

Cooper founded Advanced Projects in his later life and served as the chairman of the board. He wanted to explore new technologies like 3-D color television productions.[2]: 374 Cooper died of cancer on April 21, 1973,[1] in San Diego.[9] His ashes were scattered at sea with full military honors.[2]: 378

Filmography

| Year | Title | Director | Producer | Writer | Cinematographer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1924 | The Lost Empire | No | No | Titles | No | Also editor |

| 1925 | Grass: A Nation's Battle for Life | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Role: Himself; Documentary |

| 1927 | Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Documentaries |

| 1929 | Captain Salisbury's Ra-Mu | No | No | No | Yes | |

| The Four Feathers | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| 1931 | Gow the Killer | No | No | No | Yes | Documentary-based exploitation film |

| 1932 | Roar of the Dragon | No | No | Story | No | |

| 1933 | King Kong | Yes | Yes | Story | No | Role: Pilot of plane that kills Kong |

| 1935 | The Last Days of Pompeii | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| 1949 | Mighty Joe Young | Yes | Yes | Story | No | Also presenter |

| 1952 | This Is Cinerama | Yes | Yes | No | No | Documentary |

References

- ^ a b c d James V. D'Arc and John N. Gillespie (2013). "Merian C. Cooper papers". Prepared for the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Provo, UT.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Vaz, Mark Cotta (August 2005). Living dangerously The adventures of Merian C. Cooper, creator of King Kong. Villard. ISBN 978-1-4000-6276-8.

- ^ "Notable Alumni". The Lawrenceville School. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ Smith, Dinitia (August 13, 2005). "Getting That Monkey Off His Creator's Back". The New York Times.

- ^ Lovelace, Delos; Wallace, Edgar (2005). King Kong. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-345-48496-3. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "Memoirs of King Kong Director and War Hero at Hoover". Hoover Institution. Board of Trustees of Leland Stanford Junior University. March 4, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ a b West, James E. (1931). The Boy Scouts Book of True Adventure. New York: Putnam. OCLC 8484128.

- ^ "National Archives NextGen Catalog".

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Merian C. Cooper – Forgotten hero of two nations". American Polish Cooperation Society. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Isaac Babel". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014.

- ^ Things Men Die For: About the Book. OL 6703214M.

- ^ Snusz, Zbyszek (September 25, 2012). ""Gwiaździsta eskadra" – film kręcony z gigantycznym rozmachem w 1930 roku". Naszemiasto. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ Schwartz, Rosalie (October 2004). Flying Down to Rio: Hollywood, Tourists, and Yankee Clippers. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-421-2. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ Krizanovich, Karen. "The big monkey with a big backstory: The Legend of King Kong". Picture Box Films. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ a b Lasky, Betty (1984). RKO: The Biggest Little Major of Them All. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. ISBN 0-13-781451-8.

- ^ Wallace, Edgar; Cooper, Merian C. (2005). King Kong. Modern Library. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-8129-7493-5. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ Morton, Ray (2005). King Kong: the history of a movie icon from Fay Wray to Peter Jackson. New York, NY: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. ISBN 1-55783-669-8.

- ^ "The Legacy of Kong with Author Ray Morton! | the Kaiju Transmissions Podcast".

- ^ Dawidziak, Mark (April 4, 2008). "Turner Classic Movies celebrates the 75th anniversary of 'King Kong'". Cleveland.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ "Pioneer Plans Color Films". The Wall Street Journal. November 5, 1934.

- ^ "Merian C. Cooper Productions Sunday, July 3". TCM. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ a b "Colonel Merian C. Cooper". Ozatwar. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "WW2 Air Raids over Hong Kong & South China: View pages - Gwulo: Old Hong Kong". gwulo.com. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Rowan, Terry (2015). Who's Who in Hollywood. Lulu.com. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-329-07449-1. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ a b "John Ford—Independent Profile". Hollywood Renegades. Cobblestone Entertainment. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Eckstein, Arthur M. (February 2004). The Searchers: Essays and Reflections on John Ford's Classic Western. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-3056-2. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Around the World". Time. August 29, 1927. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- ^ "'Mighty Joe Young' (1949)". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ Pitts, Michael R. (2014). RKO radio pictures horror, science fiction and fantasy films, 1930–1956. Mcfarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6047-2. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ^ Rausch, Andrew J. (July 2002). The Hundred Greatest American Films: A Quiz Book. Citadel. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-8065-2337-8. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ "1952 Academy Awards® Winners and History". AMC. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ Conradt, Stacy (July 2016). "6 Misspellings on the Hollywood Walk of Fame". mental_floss. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ Vaz, M. Living Dangerously: The Adventures of Merian C. Cooper, Creator of King Kong. Villard (2005), pp. 386–91.

- ^ Critchlow, Donald T. (October 21, 2013). When Hollywood Was Right: How Movie Stars, Studio Moguls, and Big Business Remade American Politics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107650282.

Bibliography

- Cooper, Merian C. (February 1928). "The Warfare of the Jungle Folk: Campaigning Against Tigers, Elephants, and Other Wild Animals in Northern Siam". National Geographic: 233–68.

- Cisek, Janusz (2002). Kosciuszko, We Are Here!. McFarland. ISBN 9780786412402. OCLC 49871871.

- I'm King Kong!—The Exploits of Merian C. Cooper (2005), TCM documentary on Cooper, directed by Kevin Brownlow.

External links

- Merian C. Cooper at IMDb

- Cooper's polish-soviet war

- mini-bio and pictures of Cooper as a teenager on JaxHistory.Com

Archival materials

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Good articles

- Use mdy dates from January 2015

- Pages using infobox military person with embed

- Articles with hCards

- Commons category link from Wikidata

- 1893 births

- 1973 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- American anti-communists

- American male film actors

- American people of English descent

- American prisoners of war in World War I

- Aviators from Florida

- Bomber pilots

- California Republicans

- Deaths from cancer in California

- Film directors from Florida

- Film producers from Florida

- Florida Republicans

- Lawrenceville School alumni

- Mass media people from Jacksonville, Florida

- Military personnel from Florida

- Polish people of the Polish–Soviet War

- Recipients of the Cross of Valour (Poland)

- Recipients of the Silver Cross of the Virtuti Militari

- Shot-down aviators

- United States Army Air Forces bomber pilots of World War II

- United States Army Air Forces officers

- United States Army Air Service pilots of World War I

- United States Army colonels

- United States Army personnel of World War I

- World War I prisoners of war held by Germany