Preventable causes of death

Preventable causes of death are causes of death related to risk factors which could have been avoided.[1] The World Health Organization has traditionally classified death according to the primary type of disease or injury. However, causes of death may also be classified in terms of preventable risk factors—such as smoking, unhealthy diet, sexual behavior, and reckless driving—which contribute to a number of different diseases. Such risk factors are usually not recorded directly on death certificates, although they are acknowledged in medical reports.

Worldwide

It is estimated that of the roughly 150,000 people who die each day across the globe, about two thirds—100,000 per day—die of age-related causes.[2] In industrialized nations the proportion is much higher, reaching 90 percent.[2] Thus, albeit indirectly, biological aging (senescence) is by far the leading cause of death. Whether senescence as a biological process itself can be slowed, halted, or even reversed is a subject of current scientific speculation and research.[3]

2001 figures

Risk factors associated with the leading causes of preventable death worldwide as of the year 2001, according to researchers working with the Disease Control Priorities Network (DCPN)[4]:[5]

| Cause | Number of deaths resulting (millions per year) |

|---|---|

| Hypertension | 7.8 |

| Smoking tobacco | 5.4 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 3.8 |

| Sexually transmitted diseases | 3.0 |

| Poor diet | 2.8 |

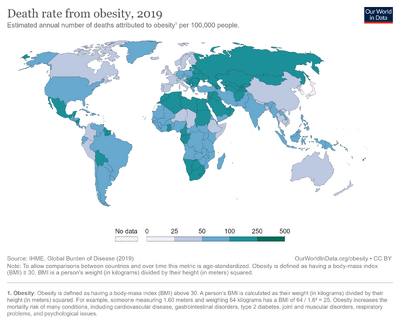

| Overweight and obesity | 2.5 |

| Physical inactivity | 2.0 |

| Malnutrition | 1.9 |

| Indoor air pollution from solid fuels | 1.8 |

| Unsafe water and poor sanitation | 1.6 |

By contrast, the World Health Organization (WHO)'s 2008 statistics Archived 2014-02-04 at the Wayback Machine list only causes of death, and not the underlying risk factors.

In 2001, on average 29,000 children died of preventable causes each day (that is, about 20 deaths per minute). The authors provide the context:

About 56 million people died in 2001. Of these, 10.6 million were children, 99% of whom lived in low-and-middle-income countries. More than half of child deaths in 2001 were attributable to acute respiratory infections, measles, diarrhea, malaria, and HIV/AIDS.[5]

United States

The three risk factors most commonly leading to preventable death in the population of the United States are smoking, high blood pressure, and being overweight.[6] Pollution from fossil fuel burning kills roughly 200,000/year.[1] Archived 2021-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

Accidental death

Annual number of deaths and causes

| Cause | Number | Percent of total | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preventable medical errors in hospitals | 210,000 to 448,000[9] | 23.1% | Estimates vary, significant numbers of preventable deaths also result from errors outside of hospitals. |

| Adverse events in hospitals in low- and middle-income countries | 2.6 million deaths[10] | "one of the 10 leading causes of death and disability in the world" | |

| Smoking tobacco | 435,000[7] | 18.1% | |

| Obesity | 111,900[11] | 4.6% | There was considerable debate about the differences in the numbers of obesity-related diseases.[12] The value here reflects the death rate for obesity that has been found to be the most accurate of the debated values.[13] Note, however, that being overweight but not obese was associated with fewer deaths (not more deaths) relative to being normal weight.[11] |

| Alcohol | 85,000[7] | 3.5% | |

| Infectious diseases | 75,000[7] | 3.1% | |

| Toxic agents including toxins, particulates and radon | 55,000[7] | 2.3% | |

| Traffic collisions | 43,000[7] | 1.8% | |

| Preventable colorectal cancers | 41,400 | 1.7% | Colorectal cancer (bowel cancer, colon cancer) caused 51,783 deaths in the US in 2011.[14] About 80 percent[15] of colorectal cancers begin as benign growths, commonly called polyps, which can be easily detected and removed during a colonoscopy. Accordingly, the tabulated figure assumes that 80 percent of the fatal cancers could have been prevented. |

| Firearms deaths | 31,940[16] | 1.3% | Suicide: 19,766; homicide: 11,101; accidents: 852; unknown: 822. |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 20,000[7] | 0.8% | |

| Substance use disorder | 17,000[7][needs update] | 0.7% |

Among children worldwide

Various injuries are the leading cause of death in children 9–17 years of age. In 2008, the top five worldwide unintentional injuries in children are as follows:[17]

| Cause | Number of deaths resulting |

|---|---|

| Traffic collision |

260,000 per year |

| Drowning |

175,000 per year |

| Viruses |

96,000 per year |

| Falls |

47,000 per year |

| Toxins |

45,000 per year |

See also

- Accidental death – Unnatural death caused by accident – Unnatural death caused by accident

- Alcohol and health – Health effects of drinking alcohol – Health effects of drinking alcohol

- Lifestyle medicine – Aspects of medicine focused on food, exercise, and sleep – Aspects of medicine focused on food, exercise, and sleep

- List of causes of death by rate

- Health effects of tobacco § Mortality

- Preventive healthcare – Prevention of the occurrence of diseases – Prevention of the occurrence of diseases

- Public health – Preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through organized efforts and informed choices of society and individuals – Preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through organized efforts and informed choices of society and individuals

References

- ↑ Danaei, Goodarz; Ding, Eric L.; Mozaffarian, Dariush; Taylor, Ben; Rehm, Jürgen; Murray, Christopher J. L.; Ezzati, Majid (2009-04-28). "The Preventable Causes of Death in the United States: Comparative Risk Assessment of Dietary, Lifestyle, and Metabolic Risk Factors". PLOS Medicine. 6 (4): e1000058. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. ISSN 1549-1277. PMC 2667673. PMID 19399161.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Aubrey D.N.J, de Grey (2007). "Life Span Extension Research and Public Debate: Societal Considerations" (PDF). Studies in Ethics, Law, and Technology. 1 (1, Article 5). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.395.745. doi:10.2202/1941-6008.1011. S2CID 201101995. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2011. Archived February 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "SENS Foundation". Archived from the original on 2019-05-27. Retrieved 2012-10-10. Archived 2019-05-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "DCP3". washington.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-01-28. Archived 2013-01-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ (May 2006). "Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data". Lancet. 367 (9524): 1747–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. PMID 16731270. S2CID 22609505.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Danaei; Ding; Mozaffarian; Taylor; Rehm; Murray; Ezzati (2009). "The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors". PLOS Medicine. 6 (4): e1000058. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. PMC 2667673. PMID 19399161.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL (March 2004). "Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000" (PDF). JAMA. 291 (10): 1238–45. doi:10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. PMID 15010446. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-06-20. Retrieved 2008-08-28. Archived 2019-06-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 National Vital Statistics Report, Vol. 50, No. 15, September 16, 2002 Archived May 5, 2019, at the Wayback Machine as compiled at "Death Statistics Tables". Archived from the original on 2009-02-21. Retrieved 2009-06-21. Archived 2009-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ James, John T. (2013). "A New, Evidence-based Estimate of Patient Harms Associated with Hospital Care". Journal of Patient Safety. 9 (3): 122–28. doi:10.1097/PTS.0b013e3182948a69. PMID 23860193. S2CID 15280516.

- ↑ "Patient Safety". WHO. 13 September 2019. Archived from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022. Archived 16 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Flegal, K.M., B.I. Graubard, D.F. Williamson, and M.H. Gail. (2005). "Obesity". Journal of the American Medical Association. 293 (15): 1861–67. doi:10.1001/jama.293.15.1861. PMID 15840860.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Flegal, Katherine M. (2021). "The obesity wars and the education of a researcher: A personal account". Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 67: 75–79. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2021.06.009. PMID 34139265. S2CID 235470848.

- ↑ "Controversies in Obesity Mortality: A Tale of Two Studies" (PDF). RTI International. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2014-02-21. Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "Colorectal Cancer Statistics". Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved January 12, 2015. Archived May 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Carol A. Burke; Laura K. Bianchi. "Colorectal Neoplasia". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2015. Archived October 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2011" (PDF). CDC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2014-02-21. Archived 2014-02-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "BBC News | Special Reports | UN raises child accidents alarm". BBC News. December 10, 2008. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2010. Archived August 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2002

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- Wikipedia articles in need of updating from August 2022

- All Wikipedia articles in need of updating

- Causes of death

- Death-related lists

- Demography

- Prevention

![Leading preventable causes of death in the United States in the year 2000.[7] Note: This data is outdated and has been significantly revised, especially for obesity-related deaths.[6]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/07/Preventable_causes_of_death.svg/277px-Preventable_causes_of_death.svg.png)

![Leading causes of accidental death in the United States by age group as of 2002[update].[8]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Causes_of_accidental_death_by_age_group.png/294px-Causes_of_accidental_death_by_age_group.png)

![Leading causes of accidental death in the United States as of 2002[update], as a percentage of deaths in each group.[8]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/Causes_of_accidental_death_by_age_group_%28percent%29.png/296px-Causes_of_accidental_death_by_age_group_%28percent%29.png)