Allergic rhinitis

| Allergic rhinitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Hay fever, pollinosis, allergic rhinosinusitis | |

| |

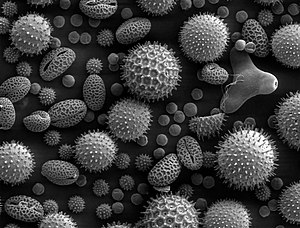

| Pollen grains from a variety of plants, enlarged 500 times | |

| Specialty | Allergy and immunology |

| Symptoms | Stuffy itchy nose, sneezing, red, itchy, and watery eyes, swelling around the eyes, itchy ears[1] |

| Usual onset | 20 to 40 years old[2] |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors[3] |

| Risk factors | Asthma, allergic conjunctivitis, atopic dermatitis[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, skin prick test, blood tests for specific antibodies[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Common cold[3] |

| Prevention | Exposure to animals early in life[3] |

| Medication | Nasal steroids, antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, cromolyn sodium, leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast, allergen immunotherapy[5][6] |

| Frequency | ~20% (Western countries)[2][7] |

Allergic rhinitis, also known as hay fever, is a type of inflammation in the nose which occurs when the immune system overreacts to allergens in the air.[6] Signs and symptoms include a runny or stuffy nose, sneezing, red, itchy, and watery eyes, and swelling around the eyes.[1] The fluid from the nose is usually clear.[2] Symptom onset is often within minutes following allergen exposure and can affect sleep, and the ability to work or study.[2][8] Some people may develop symptoms only during specific times of the year, often as a result of pollen exposure.[3] Many people with allergic rhinitis also have asthma, allergic conjunctivitis, or atopic dermatitis.[2]

Allergic rhinitis is typically triggered by environmental allergens such as pollen, pet hair, dust, or mold.[3] Inherited genetics and environmental exposures contribute to the development of allergies.[3] Growing up on a farm and having multiple siblings decreases this risk.[2] The underlying mechanism involves IgE antibodies that attach to an allergen, and subsequently result in the release of inflammatory chemicals such as histamine from mast cells.[2] Diagnosis is typically based on a combination of symptoms and a skin prick test or blood tests for allergen-specific IgE antibodies.[4] These tests, however, can be falsely positive.[4] The symptoms of allergies resemble those of the common cold; however, they often last for more than two weeks and typically do not include a fever.[3]

Exposure to animals early in life might reduce the risk of developing these specific allergies.[3] Several different types of medications reduce symptoms: including nasal steroids, antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine, cromolyn sodium, and leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast.[5] Oftentimes, medications do not completely control symptoms, and they may also have side effects.[2] Exposing people to larger and larger amounts of allergen, known as allergen immunotherapy (AIT), may be effective.[9] The allergen can be given as an injection under the skin or as a tablet under the tongue.[6] Treatment typically lasts three to five years, after which benefits may be prolonged.[6]

Allergic rhinitis is the type of allergy that affects the greatest number of people.[10] In Western countries, between 10 and 30% of people are affected in a given year.[2][7] It is most common between the ages of twenty and forty.[2] The first accurate description is from the 10th-century physician Rhazes.[11] In 1859, Charles Blackley identified pollen as the cause.[12] In 1906, the mechanism was determined by Clemens von Pirquet.[10] The link with hay came about due to an early (and incorrect) theory that the symptoms were brought about by the smell of new hay.[13][14]

Signs and symptoms

The characteristic symptoms of allergic rhinitis are: rhinorrhea (excess nasal secretion), itching, sneezing fits, and nasal congestion and obstruction.[15] Characteristic physical findings include conjunctival swelling and erythema, eyelid swelling with Dennie–Morgan folds, lower eyelid venous stasis (rings under the eyes known as "allergic shiners"), swollen nasal turbinates, and middle ear effusion.[16]

There can also be behavioral signs; in order to relieve the irritation or flow of mucus, people may wipe or rub their nose with the palm of their hand in an upward motion: an action known as the "nasal salute" or the "allergic salute". This may result in a crease running across the nose (or above each nostril if only one side of the nose is wiped at a time), commonly referred to as the "transverse nasal crease", and can lead to permanent physical deformity if repeated enough.[17]

People might also find that cross-reactivity occurs.[18] For example, people allergic to birch pollen may also find that they have an allergic reaction to the skin of apples or potatoes.[19] A clear sign of this is the occurrence of an itchy throat after eating an apple or sneezing when peeling potatoes or apples. This occurs because of similarities in the proteins of the pollen and the food.[20] There are many cross-reacting substances. Hay fever is not a true fever, meaning it does not cause a core body temperature in the fever over 37.5–38.3 °C (99.5–100.9 °F).

Cause

Allergic rhinitis triggered by the pollens of specific seasonal plants is commonly known as "hay fever", because it is most prevalent during haying season. However, it is possible to have allergic rhinitis throughout the year. The pollen that causes hay fever varies between individuals and from region to region; in general, the tiny, hardly visible pollens of wind-pollinated plants are the predominant cause. Pollens of insect-pollinated plants are too large to remain airborne and pose no risk. Examples of plants commonly responsible for hay fever include:

- Trees: such as pine (Pinus), birch (Betula), alder (Alnus), cedar (Cedrus), hazel (Corylus), hornbeam (Carpinus), horse chestnut (Aesculus), willow (Salix), poplar (Populus), plane (Platanus), linden/lime (Tilia), and olive (Olea). In northern latitudes, birch is considered to be the most common allergenic tree pollen, with an estimated 15–20% of people with hay fever sensitive to birch pollen grains. A major antigen in these is a protein called Bet V I. Olive pollen is most predominant in Mediterranean regions. Hay fever in Japan is caused primarily by sugi (Cryptomeria japonica) and hinoki (Chamaecyparis obtusa) tree pollen.

- "Allergy friendly" trees include: ash (female only), red maple, yellow poplar, dogwood, magnolia, double-flowered cherry, fir, spruce, and flowering plum.[22]

- Grasses (Family Poaceae): especially ryegrass (Lolium sp.) and timothy (Phleum pratense). An estimated 90% of people with hay fever are allergic to grass pollen.

- Weeds: ragweed (Ambrosia), plantain (Plantago), nettle/parietaria (Urticaceae), mugwort (Artemisia Vulgaris), Fat hen (Chenopodium), and sorrel/dock (Rumex)

Allergic rhinitis may also be caused by allergy to Balsam of Peru, which is in various fragrances and other products.[23][24][25]

Predisposing factors to allergic rhinitis include eczema (atopic dermatitis) and asthma. These three conditions can often occur together which is referred to as the atopic triad.[26] Additionally, environmental exposures such as air pollution and maternal tobacco smoking can increase an individual's chances of developing allergies.[26]

Diagnosis

Allergy testing may reveal the specific allergens to which an individual is sensitive. Skin testing is the most common method of allergy testing.[27] This may include a patch test to determine if a particular substance is causing the rhinitis, or an intradermal, scratch, or other test. Less commonly, the suspected allergen is dissolved and dropped onto the lower eyelid as a means of testing for allergies. This test should be done only by a physician, since it can be harmful if done improperly. In some individuals not able to undergo skin testing (as determined by the doctor), the RAST blood test may be helpful in determining specific allergen sensitivity. Peripheral eosinophilia can be seen in differential leukocyte count.

Allergy testing is not definitive. At times, these tests can reveal positive results for certain allergens that are not actually causing symptoms, and can also not pick up allergens that do cause an individual's symptoms. The intradermal allergy test is more sensitive than the skin prick test, but is also more often positive in people that do not have symptoms to that allergen.[28]

Even if a person has negative skin-prick, intradermal and blood tests for allergies, he/she may still have allergic rhinitis, from a local allergy in the nose. This is called local allergic rhinitis.[29] Specialized testing is necessary to diagnose local allergic rhinitis.[30]

Classification

Allergic rhinitis may be seasonal, perennial, or episodic.[8] Seasonal allergic rhinitis occurs in particular during pollen seasons. It does not usually develop until after 6 years of age. Perennial allergic rhinitis occurs throughout the year. This type of allergic rhinitis is commonly seen in younger children.[31]

Allergic rhinitis may also be classified as Mild-Intermittent, Moderate-Severe intermittent, Mild-Persistent, and Moderate-Severe Persistent. Intermittent is when the symptoms occur <4 days per week or <4 consecutive weeks. Persistent is when symptoms occur >4 days/week and >4 consecutive weeks. The symptoms are considered mild with normal sleep, no impairment of daily activities, no impairment of work or school, and if symptoms are not troublesome. Severe symptoms result in sleep disturbance, impairment of daily activities, and impairment of school or work.[32]

Local allergic rhinitis

Local allergic rhinitis is an allergic reaction in the nose to an allergen, without systemic allergies. So skin-prick and blood tests for allergy are negative, but there are IgE antibodies produced in the nose that react to a specific allergen. Intradermal skin testing may also be negative.[30]

The symptoms of local allergic rhinitis are the same as the symptoms of allergic rhinitis, including symptoms in the eyes. Just as with allergic rhinitis, people can have either seasonal or perennial local allergic rhinitis. The symptoms of local allergic rhinitis can be mild, moderate, or severe. Local allergic rhinitis is associated with conjunctivitis and asthma.[30]

In one study, about 25% of people with rhinitis had local allergic rhinitis.[33] In several studies, over 40% of people having been diagnosed with nonallergic rhinitis were found to actually have local allergic rhinitis.[29] Steroid nasal sprays and oral antihistamines have been found to be effective for local allergic rhinitis.[30]

As of 2014, local allergenic rhinitis had mostly been investigated in Europe; in the United States, the nasal provocation testing necessary to diagnose the condition was not widely available.[34]: 617

Prevention

Prevention often focuses on avoiding specific allergens that cause an individual's symptoms. These methods include not having pets, not having carpets or upholstered furniture in the home, and keeping the home dry.[35] Specific anti-allergy zippered covers on household items like pillows and mattresses have also proven to be effective in preventing dust mite allergies.[27] Interestingly, studies have shown that growing up on a farm and having many older brothers and sisters can decrease an individual's risk for developing allergic rhinitis.[2]

Treatment

The goal of rhinitis treatment is to prevent or reduce the symptoms caused by the inflammation of affected tissues. Measures that are effective include avoiding the allergen.[15] Intranasal corticosteroids are the preferred medical treatment for persistent symptoms, with other options if this is not effective.[15][36] Second line therapies include antihistamines, decongestants, cromolyn, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and nasal irrigation.[15] Antihistamines by mouth are suitable for occasional use with mild intermittent symptoms.[15] Mite-proof covers, air filters, and withholding certain foods in childhood do not have evidence supporting their effectiveness.[15]

Antihistamines

Antihistamine drugs can be taken orally and nasally to control symptoms such as sneezing, rhinorrhea, itching, and conjunctivitis.

It is best to take oral antihistamine medication before exposure, especially for seasonal allergic rhinitis. In the case of nasal antihistamines like azelastine antihistamine nasal spray, relief from symptoms is experienced within 15 minutes allowing for a more immediate 'as-needed' approach to dosage. There is not enough evidence of antihistamine efficacy as an add-on therapy with nasal steroids in the management of intermittent or persistent allergic rhinitis in children, so its adverse effects and additional costs must be considered.[37]

Ophthalmic antihistamines (such as azelastine in eye drop form and ketotifen) are used for conjunctivitis, while intranasal forms are used mainly for sneezing, rhinorrhea, and nasal pruritus.[38]

Antihistamine drugs can have undesirable side-effects, the most notable one being drowsiness in the case of oral antihistamine tablets. First-generation antihistamine drugs such as diphenhydramine cause drowsiness, while second- and third-generation antihistamines such as cetirizine and loratadine are less likely to.[38]

Pseudoephedrine is also indicated for vasomotor rhinitis. It is used only when nasal congestion is present and can be used with antihistamines. In the United States, oral decongestants containing pseudoephedrine must be purchased behind the pharmacy counter in an effort to prevent the manufacturing of methamphetamine.[38]Desloratadine/pseudoephedrine can also be used for this condition[citation needed]

Steroids

Intranasal corticosteroids are used to control symptoms associated with sneezing, rhinorrhea, itching, and nasal congestion.[26] Steroid nasal sprays are effective and safe, and may be effective without oral antihistamines. They take several days to act and so must be taken continually for several weeks, as their therapeutic effect builds up with time.

In 2013, a study compared the efficacy of mometasone furoate nasal spray to betamethasone oral tablets for the treatment of people with seasonal allergic rhinitis and found that the two have virtually equivalent effects on nasal symptoms in people.[39]

Systemic steroids such as prednisone tablets and intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide or glucocorticoid (such as betamethasone) injection are effective at reducing nasal inflammation,[citation needed] but their use is limited by their short duration of effect and the side-effects of prolonged steroid therapy.[40]

Other

Other measures that may be used second line include: decongestants, cromolyn, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and nonpharmacologic therapies such as nasal irrigation.[15]

Topical decongestants may also be helpful in reducing symptoms such as nasal congestion, but should not be used for long periods, as stopping them after protracted use can lead to a rebound nasal congestion called rhinitis medicamentosa.

For nocturnal symptoms, intranasal corticosteroids can be combined with nightly oxymetazoline, an adrenergic alpha-agonist, or an antihistamine nasal spray without risk of rhinitis medicamentosa.[41]

Nasal saline irrigation (a practice where salt water is poured into the nostrils), may have benefits in both adults and children in relieving the symptoms of allergic rhinitis and it is unlikely to be associated with side effects.[42][43]

Immunotherapy

Allergen immunotherapy (AIT, also termed desensitization) involves administering doses of allergens to accustom the body to substances that are generally harmless (pollen, house dust mites), thereby inducing specific long-term tolerance.[44] Allergen immunotherapy is the only treatment that alters the disease mechanism.[45] Immunotherapy can be administered orally (as sublingual tablets or sublingual drops), or by injections under the skin (subcutaneous). Subcutaneous immunotherapy is the most common form and has the largest body of evidence supporting its effectiveness.[46] Use under the tongue can take years to show a small to moderate benefit.[9]

Alternative medicine

There are no forms of complementary or alternative medicine that are evidence-based for allergic rhinitis.[27] Therapeutic efficacy of alternative treatments such as acupuncture and homeopathy is not supported by available evidence.[47][48] While some evidence shows that acupuncture is effective for rhinitis, specifically targeting the sphenopalatine ganglion acupoint, these trials are still limited.[49] Overall, the quality of evidence for complementary-alternative medicine is not strong enough to be recommended by the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.[27][50]

Epidemiology

Allergic rhinitis is the type of allergy that affects the greatest number of people.[10] In Western countries, between 10 and 30 percent of people are affected in a given year.[2] It is most common between the ages of twenty and forty.[2]

History

The first accurate description is from the 10th century physician Rhazes.[11] Pollen was identified as the cause in 1859 by Charles Blackley.[12] In 1906 the mechanism was determined by Clemens von Pirquet.[10] The link with hay came about due to an early (and incorrect) theory that the symptoms were brought about by the smell of new hay.[13][14]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Environmental Allergies: Symptoms". NIAID. April 22, 2015. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Wheatley, LM; Togias, A (29 January 2015). "Clinical practice. Allergic rhinitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (5): 456–63. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1412282. PMC 4324099. PMID 25629743.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 "Cause of Environmental Allergies". NIAID. April 22, 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Environmental Allergies: Diagnosis". NIAID. May 12, 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Environmental Allergies: Treatments". NIAID. April 22, 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Immunotherapy for Environmental Allergies". NIAID. May 12, 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dykewicz MS, Hamilos DL (February 2010). "Rhinitis and sinusitis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 125 (2 Suppl 2): S103–15. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.989. PMID 20176255.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Covar, Ronina (2018). "Allergic Disorders." Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Pediatrics, 24e Eds. NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. Chapter 38. ISBN 978-1-259-86290-8.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Boldovjáková, D; Cordoni, S; Fraser, CJ; Love, AB; Patrick, L; Ramsay, GJ; Ferguson, ASJ; Gomati, A; Ram, B (January 2021). "Sublingual immunotherapy vs placebo in the management of grass pollen-induced allergic rhinitis in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical otolaryngology : official journal of ENT-UK ; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 46 (1): 52–59. doi:10.1111/coa.13651. PMID 32979035.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Fireman, Philip (2002). Pediatric otolaryngology vol 2 (4th ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: W. B. Saunders. p. 1065. ISBN 9789997619846. Archived from the original on 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Colgan, Richard (2009). Advice to the young physician on the art of medicine. New York: Springer. p. 31. ISBN 9781441910349. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Justin Parkinson (1 July 2014). "John Bostock: The man who 'discovered' hay fever". BBC News Magazine. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hall, Marshall (May 19, 1838). "Dr. Marshall Hall on Diseases of the Respiratory System; III. Hay Asthma". The Lancet. 30 (768): 245. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)95895-2. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

With respect to what is termed the exciting cause of the disease, since the attention of the public has been turned to the subject an idea has very generally prevailed, that it is produced by the effluvium from new hay, and it has hence obtained the popular name of hay fever. [...] the effluvium from hay has no connection with the disease.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 History of Allergy. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. 2014. p. 62. ISBN 9783318021950. Archived from the original on 2016-06-10.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 Sur DK, Plesa M (1 December 2015). "Treatment of Allergic Rhinitis". Am Fam Physician. 92 (11): 985–992. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ↑ Valet RS, Fahrenholz JM (2009). "Allergic rhinitis: update on diagnosis". Consultant. 49: 610–3. Archived from the original on 2010-01-14.

- ↑ Pray, W. Steven (2005). Nonprescription Product Therapeutics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 221. ISBN 978-0781734981.

- ↑ Czaja-Bulsa G, Bachórska J (1998). "[Food allergy in children with pollinosis in the Western sea coast region]". Pol Merkur Lekarski. 5 (30): 338–40. PMID 10101519.

- ↑ Yamamoto T, Asakura K, Shirasaki H, Himi T, Ogasawara H, Narita S, Kataura A (2005). "[Relationship between pollen allergy and oral allergy syndrome]". Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 108 (10): 971–9. doi:10.3950/jibiinkoka.108.971. PMID 16285612.

- ↑ Malandain H (2003). "[Allergies associated with both food and pollen]". Allerg Immunol (Paris). 35 (7): 253–6. PMID 14626714.

- ↑ Bjermer, Leif; Westman, Marit; Holmström, Mats; Wickman, Magnus C. (16 April 2019). "The complex pathophysiology of allergic rhinitis: scientific rationale for the development of an alternative treatment option". Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology. 15 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/s13223-018-0314-1. ISSN 1710-1492. Archived from the original on 5 December 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ↑ "Allergy Friendly Trees". Forestry.about.com. 2014-03-05. Archived from the original on 2014-04-14. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ↑ Pamela Brooks (2012). The Daily Telegraph: Complete Guide to Allergies. ISBN 9781472103949. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Denver Medical Times: Utah Medical Journal. Nevada Medicine. 2010-01-01. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- ↑ George Clinton Andrews; Anthony Nicholas Domonkos (1998-07-01). Diseases of the Skin: For Practitioners and Students. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Cahill, Katherine (2018). "Urticaria, Angioedema, and Allergic Rhinitis." 'Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e' Eds. NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. Chapter 345. ISBN 978-1-259-64403-0.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 "American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology". Archived from the original on 2020-07-25.

- ↑ "Allergy Tests". Archived from the original on 2012-01-14.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Rondón, Carmen; Canto, Gabriela; Blanca, Miguel (2010). "Local allergic rhinitis: A new entity, characterization and further studies". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 10 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1097/ACI.0b013e328334f5fb. PMID 20010094.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Rondón, C; Fernandez, J; Canto, G; Blanca, M (2010). "Local allergic rhinitis: Concept, clinical manifestations, and diagnostic approach" (PDF). Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 20 (5): 364–71, quiz 2 p following 371. PMID 20945601. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-01.

- ↑ "Rush University Medical Center". Archived from the original on 2015-02-19. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ Bousquet J, Reid J, van Weel C (August 2008). "Allergic rhinitis management pocket reference 2008". Allergy. 63 (8): 990–6. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01642.x. PMID 18691301.

- ↑ Rondón C, Campo P, Galindo L, Blanca-López N, Cassinello MS, Rodriguez-Bada JL, Torres MJ, Blanca M (2012). "Prevalence and clinical relevance of local allergic rhinitis". Allergy. 67 (10): 1282–8. doi:10.1111/all.12002. PMID 22913574.

- ↑ Flint, Paul W.; Haughey, Bruce H.; Robbins, K. Thomas; Thomas, J. Regan; Niparko, John K.; Lund, Valerie J.; Lesperance, Marci M. (2014-11-28). Cummings Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323278201. Archived from the original on 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- ↑ "Prevention". nhs.uk. 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ↑ Ton, Joey (12 June 2022). "#317 Antihistamines for allergic rhinosinusitis: 'Achoo'sing the right treatment". CFPCLearn. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ↑ Nasser, M; Fedorowicz, Z; Aljufairi, H; McKerrow, W (7 July 2010). "Antihistamines used in addition to topical nasal steroids for intermittent and persistent allergic rhinitis in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD006989. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006989.pub2. PMID 20614452.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 May, J.R.; Smith, P.H. (2008). "Allergic Rhinitis". In DiPiro, J.T.; Talbert, R.L.; Yee, G.C.; Matzke, G.; Wells, B.; Posey, L.M. (eds.). Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1565–75. ISBN 978-0071478991.

- ↑ Karaki M, Akiyama K, Mori N (2013). "Efficacy of intranasal steroid spray (mometasone furoate) on treatment of patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis: comparison with oral corticosteroids". Auris Nasus Larynx. 40 (3): 277–81. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2012.09.004. PMID 23127728.

- ↑ Ohlander BO, Hansson RE, Karlsson KE (1980). "A comparison of three injectable corticosteroids for the treatment of patients with seasonal hay fever". J Int Med Res. 8 (1): 63–9. doi:10.1177/030006058000800111. PMID 7358206.

- ↑ Baroody FM, Brown D, Gavanescu L, Detineo M, Naclerio RM (2011). "Oxymetazoline adds to the effectiveness of fluticasone furoate in the treatment of perennial allergic rhinitis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 127 (4): 927–34. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.037. PMID 21377716.

- ↑ Head, Karen; Snidvongs, Kornkiat; Glew, Simon; Scadding, Glenis; Schilder, Anne GM; Philpott, Carl; Hopkins, Claire (2018-06-22), "Saline irrigation for allergic rhinitis" (PDF), The Cochrane Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, vol. 6, pp. CD012597, doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012597.pub2, PMC 6513421, PMID 29932206, archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-21, retrieved 2018-11-19

- ↑ Moe, Samantha (1 February 2016). "#155 "I got water up my nose." From swimming accident to rhinosinusitis cure?". CFPCLearn. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ↑ Van Overtvelt L. et al. Immune mechanisms of allergen-specific sublingual immunotherapy. Revue française d’allergologie et d’immunologie clinique. 2006; 46: 713–720.

- ↑ Creticos, Peter. "Subcutaneous immunotherapy for allergic disease: Indications and efficacy". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 2020-07-25.

- ↑ Calderon, M. A.; Alves, B.; Jacobson, M.; Hurwitz, B.; Sheikh, A.; Durham, S. (2007-01-24). "Allergen injection immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD001936. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001936.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7017974. PMID 17253469.

- ↑ Passalacqua G, Bousquet PJ, Carlsen KH, Kemp J, Lockey RF, Niggemann B, Pawankar R, Price D, Bousquet J (2006). "ARIA update: I—Systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine for rhinitis and asthma". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 117 (5): 1054–62. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1308. PMID 16675332.

- ↑ Terr A (2004). "Unproven and controversial forms of immunotherapy". Clin Allergy Immunol. 18 (1): 703–10. PMID 15042943.

- ↑ Fu, Qinwei; Zhang, Lanzhi; Liu, Yang; Li, Xinrong; Yang, Yepeng; Dai, Menglin; Zhang, Qinxiu (2019). "Effectiveness of Acupuncturing at the Sphenopalatine Ganglion Acupoint Alone for Treatment of Allergic Rhinitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2019: 6478102. doi:10.1155/2019/6478102. ISSN 1741-427X. PMC 6434301. PMID 30992709.

- ↑ Witt CM, Brinkhaus B (July 2010). "Efficacy, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of acupuncture for allergic rhinitis — An overview about previous and ongoing studies". Autonomic Neuroscience. 157 (1–2): 42–5. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2010.06.006. PMID 20609633.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- CS1 maint: url-status

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2015

- Articles with Curlie links

- Allergology

- Steroid-responsive inflammatory conditions

- Type I hypersensitivity

- RTT

- RTTEM