Avicephala

| Avicephala | |

|---|---|

| |

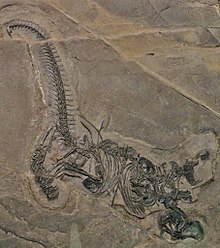

| Skeleton of the drepanosaur Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus | |

| |

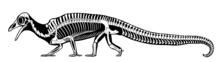

| Skeleton of the weigeltisaurid Weigeltisaurus jaekeli | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Neodiapsida |

| Clade: | †Avicephala Senter, 2004 |

| Included subgroups | |

Avicephala ("bird heads") is a potentially polyphyletic grouping of extinct diapsid reptiles that lived during the Late Permian and Triassic periods characterised by superficially bird-like skulls and arboreal lifestyles. As a clade, Avicephala is defined as including the gliding weigeltisaurids and the arboreal drepanosaurs to the exclusion of other major diapsid groups. This relationship is not recovered in the majority of phylogenetic analyses of early diapsids and so Avicephala is typically regarded as an artificial or unnatural grouping. However, the clade was recovered again in 2021 following a redescription of Weigeltisaurus, raising the possibility that the clade may be valid after all, although subsequent analyses have not supported this result.

Description

Avicephalans were named in reference to their pointed, lightly constructed, superficially bird-like skulls. The resemblance is especially striking in some drepanosaurs such as Megalancosaurus which possess long, pointed snouts and expanded, rounded craniums. The three-dimensionally preserved Avicranium has even been proposed to have been toothless and had forward-facing eyes, although the construction of its skull is debated.[1][2] These superficial similarities to birds led some scientists to hypothesise that birds were derived from various avicephalans, although the well established relationship of birds to theropod dinosaurs indicates that these similarities arose only through convergent evolution.[3]

Although bird-like in some respects, avicephalans also possess a variety of archaic and unique characteristics as well, including some associated with an arboreal lifestyle. Drepanosaurs possess a suite of chameleon-like skeletal features, such as opposable digits on the hands and feet and prehensile tails—tipped with a bony hook in some genera like Drepanosaurus.[4] Weigeltisaurids on the other hand possessed wing-like gliding membranes (patagia) supported by elongated bony rods along their bodies, novel structures analogous to ribs of the modern gliding Draco lizard. Weigeltisaurids also had toes that were similarly proportioned to living arboreal lizards. Although both groups are highly derived, they do share some similarities, namely they have relatively unossified skeletons lacking intercentra between their vertebrae, as well as proportionately tall, thin shoulder blades.[5]

The enigmatic Triassic reptile Longisquama was initially included as an avicephalan when the clade was first defined as a relative of Coelurosauravus.[3] However, due to the limited knowledge of its anatomy, Longisquama has been excluded from many subsequent phylogenetic analyses as its true relationships are difficult to discern.[6]

History of classification

The phylogenetic relationships of both drepanosaurs and weigeltisaurs, as well as Longisquama, have historically been difficult to pin down. Drepanosaurs and weigeltisaurids were first suggested to form a clade together by John Merck in an abstract presented to the 2003 annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.[7] The same conclusion would be reached by Phil Senter in a paper in 2004, who named this clade Avicephala and found it to be the sister taxon to Neodiapsida (defined wherein as the clade containing "Younginiforms" and all living diapsids).

Within Avicephala, Senter found two clades, one that he named Simiosauria (equivalent to Drepanosauromorpha), and another containing Coelurosauravus and Longisquama. The cladogram below depicts the result of his analysis:[3]

| Avicephala | |

Later research, including Renesto and Binelli (2006) and Renesto et al. (2010), argued that the phylogenetic analysis of Senter (2004) was flawed due to the absence of available data for drepanosaur skulls at the time and the exclusion of particular diapsid groups, such as pterosaurs. Renesto and colleagues (2010) recommended abandoning Avicephala for these reasons (as well as defining a new clade, Drepanosauromorpha, to replace Simiosauria following the guidelines of the PhyloCode). They instead found drepanosauromorphs to be archosauromorphs, possibly related to Prolacertiformes, and unrelated to weigeltisaurids or other early diapsids.[6][8]

Drepanosauromorphs would later be argued to be early-diverging diapsids once again following the description of the three-dimensionally preserved skull of Avicranium in 2017, interpreted as possessing archaic features of their skull anatomy. Still, drepanosaurs and weigeltisaurids remained as separate lineages in the study's phylogenetic analysis, with each being successively closer to living diapsids.[1]

Avicephala would not be recovered again until 2021 following the redescription of Weigeltisaurus by Adam Pritchard and colleagues, wherein the phylogenetic analysis found a clade comprising drepanosauromorphs and weigeltisaurids. They identified four unambiguous synapomorphies (shared unique traits) supporting Avicephala: the absence of both cervical and dorsal intercentra, a length/height ratio for the scapula between 0.4 and 0.25, and no outer process on the fifth metatarsal.[5]

Consequently, they provided an updated definition for Avicephala as the modern definition of Neodiapsida now includes both drepanosaurs and weigeltisaurids. Avicephala is now cladistically defined as "including all taxa more closely related to Weigeltisaurus jaekeli Weigelt 1930 and Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus Pinna 1979 than to Petrolacosaurus kansensis Lane 1945, Orovenator mayorum Reisz, Modesto & Scott, 2011, Claudiosaurus germaini Carroll, 1978, Youngina capensis Broom 1914, or Sauria Macartney 1802". Despite this result, they noted that should Avicephala not be recovered as monophyletic in future analyses they recommend that the taxon be abandoned once again. Their results are shown simplified in the left cladogram below.[5]

A study by Valentin Buffa and colleagues published in 2024 set out to test the revived monophyly of Avicephala following their reinterpretation of the skull of the drepanosaur Avicranium. Like most previous analyses they did not recover a monophyletic Avicephala, with weigeltisaurids once again recovered as stem-saurians (albeit more crownward than typical of prior analyses) and drepanosauromorphs likewise as archosauromorphs, although uniquely close relatives of Trilophosauridae within Allokotosauria, a novel position for them. The simplified results of this analysis are shown in the right cladogram below, highlighting 'avicephalans'.[2]

Buffa et al. argued that most of the shared traits both Senter and Pritchard proposed to unite Avicephala were commonly distributed enough throughout diapsids to be congruent with multiple possible evolutionary scenarios, while others were less similar between the two than previously thought (such as the nature of the inclined rear margin of the skull). Only two of Senter's original synapomorphies are common to both groups but rare in other Permo–Triassic: the subequal lengths of the third and fourth metapodials (and consequent symmetrical hands and feet). However, they may be attributable to convergent evolution due to similar arboreal lifestyles, among other shared traits. Constraining Avicephala to be monophyletic in their dataset was four steps less parsimonious, and significantly reduced the overall resolution of diapsid relationships. Both of these results suggest that Avicephala is not likely to be a true clade.[2]

Pritchard et al. (2021): Monophyletic Avicephala[5]

Buffa et al. (2024): Non-monophyletic Avicephala[2]

| Neodiapsida | 'Avicephalans' |

References

- ^ a b Pritchard, A. C.; Nesbitt, S. J. (2017). "A bird-like skull in a Triassic diapsid reptile increases heterogeneity of the morphological and phylogenetic radiation of Diapsida". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (10): 170499. Bibcode:2017RSOS....470499P. doi:10.1098/rsos.170499. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 5666248. PMID 29134065.

- ^ a b c d Buffa, V.; Frey, E.; Steyer, J.-S.; Laurin, M. (2024). "'Birds' of two feathers: Avicranium renestoi and the paraphyly of bird-headed reptiles (Diapsida: 'Avicephala')". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. zlae050. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlae050.

- ^ a b c Senter, P. (2004). "Phylogeny of Drepanosauridae (Reptilia: Diapsida)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 2 (3): 257–268. doi:10.1017/S1477201904001427. S2CID 83840423.

- ^ Renesto, S. (2000). "Bird-like head on a chameleon body: new specimens of the enigmatic diapsid reptile Megalancosaurus from the Late Triassic of northern Italy". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 106 (2): 157–180. doi:10.13130/2039-4942/5396.

- ^ a b c d Pritchard, Adam C.; Sues, H.-D.; Scott, D.; Reisz, R. R. (2021). "Osteology, relationships and functional morphology of Weigeltisaurus jaekeli (Diapsida, Weigeltisauridae) based on a complete skeleton from the Upper Permian Kupferschiefer of Germany". PeerJ. 9: e11413. doi:10.7717/peerj.11413. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 8141288. PMID 34055483.

- ^ a b Renesto, S.; Spielmann, J. A.; Lucas, S. G.; Spagnoli, G. T. (2010). "The taxonomy and paleobiology of the Late Triassic (Carnian-Norian: Adamanian-Apachean) drepanosaurs (Diapsida: Archosauromorpha: Drepanosauromorpha)". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 46: 1–81.

- ^ Merck, J. W. (2003). "An arboreal radiation of non-saurian diapsids" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (Supp 3): 78A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2003.10010538. S2CID 220410105.

- ^ Renesto, S.; Binelli, G. (2006). "Vallesaurus cenensis Wild, 1991, a drepanosaurid (Reptilia, Diapsida) from the Late Triassic of northern Italy". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 112 (1): 77–94. doi:10.13130/2039-4942/5851.