Wikipedia:Myth versus fiction

This is an essay on the Wikipedia:Neutral point of view policies. It contains the advice or opinions of one or more Wikipedia contributors. This page is not an encyclopedia article, nor is it one of Wikipedia's policies or guidelines, as it has not been thoroughly vetted by the community. Some essays represent widespread norms; others only represent minority viewpoints. |

| This page in a nutshell: Be careful when using the words "fiction" and "myth." While related, they are not interchangeable, and may even be insulting if used in the wrong way. |

People can throw words around casually and imprecisely, but when writing encyclopedia articles, we should strive for accuracy and recognize the clear distinctions between related concepts.

Fiction is written by authors who are well aware that they are creating a work that does not purport to be the truth. The recipients of fictional works are for the most part well aware that the work is fictional, but they like fiction because it is entertaining, and potentially also inspiring and illuminating.

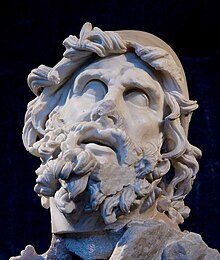

Myth, on the other hand, is usually of uncertain origin and authorship, and in many cases, seems to have developed in layers over long periods of time. In many cases it was and is spread by people who sincerely believe the myth to be true.

Almost no sane person believes that the works of William Shakespeare or Mary Shelley or Charles Dickens or Ernest Hemingway or Agatha Christie or Robert A. Heinlein are factual accounts. However many millions of people might believe that the myths of their culture or religion are true, including cases which have been scientifically debunked[vague] such as the Noah's Ark myth. Calling the story "fictional" implies that one or a few people thousands of years ago deliberately created a false story, whereas it is possible that the people who originally set the ancient myth to writing genuinely believed that it is the truth, as they understood truth. It is also possible that the myth was originally created as a fiction for the purpose of education or illustrating a point, or that it was created originally as a deliberate lie for ulterior purposes, and today it is not always possible to determine the motives of the original authors, whomever they may have been.

Myth

[edit]Our own article on myth defines it as "a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths."

Myth implies a story with a grain of truth that has grown long in the telling. Its authors may well have considered the myth to be true, or the myth might even be true, but that can no longer be proven.

There are places where the use of myth may seem obvious, but would in fact be inappropriate. Take for example Jesus. While the skeptical reader might find the stories of his miracles to be nothing more than myth, historians generally agree that Jesus was a real person. Thus, his article describes him as a real person, whilst recognizing the Christ myth theory. The article gets around the historicity problem by splitting into two main parts: the account of Jesus as provided in the Gospels, and the perspective of historians. Rather than describing the Gospels as fictional, the historical section instead challenges their reliability.

But not all Biblical stories are alike. While the story of Jesus is not generally characterized as mythical, a story like Noah's Ark has a more tenuous basis in truth. While there are theories about a localized Black Sea deluge, the global geological record makes it clear that there was no globe spanning flood. The Ark, as Biblically described, has been scientifically debunked[vague][citation needed]. But that is not to say that the Ark is fictional. The authors of the story likely believed it to be true. It forms part of the origin story of a major religion. It may have taken its grain of truth from real events, such as a catastrophic local flood. Fiction implies that the author knew they were writing a falsehood. Perhaps the author of the Ark myth did intend it as a fiction. But the author's intent is now unknowable, and the cultural context around the Ark story means that it is properly classified as a myth, not a fiction.

The uncertainty of historicity

[edit]

A sometimes key aspect of myths is that they can no longer be proven true or false. While humanity has done a pretty decent job at keeping records over the last five thousand years, the ravages of time have destroyed large swathes of the historical record. Further, many historical aspects were not written down, or were written down by biased parties. That is not to say that all exaggerated history is mythical. Much of the job of historians and the Wikipedia editor is to tease apart the real from the exaggerated. Take for example the Gallic Wars, fought from 58–50 BC by Julius Caesar. The only written account comes from – you guessed it – Julius Caesar himself. Thus he makes his exploits in the war seem far more important than they were really were. This exaggeration makes it into other historical sources, which claim that Caesar slew millions and suffered not a single casualty. Modern authors have pointed out the impossibility of that. Caesar certainly exaggerated himself to mythical levels. But it would be incorrect to describe the Wars as mythical. Archeological finds clearly indicate they were fought. The uncertainty of historicity is thus the extent of Caesar's accomplishments, not whether they happened in the first place. This can be resolved by careful use of secondary sources, which should provide appropriate discussion of the primary source's failings.

Historical exaggeration is not true myth. While historical exaggeration may inflate the accomplishments of certain figures, it can usually be appropriately handled by competent historians.

This does not mean that all things which cannot be proven true or false are myths. Many conspiracy theories fall in this space, but a conspiracy theory should never be classified as a myth. Though classifying them as fictional would also be inaccurate (as the saying goes "Don't call him dumb as a rock. That's insulting to the rock.") They should be described as they are: conspiracy theories.

Fiction

[edit]

Our own article on fiction defines it as "any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying individuals, events, or places that are imaginary or in ways that are imaginary."

The blurry line

[edit]Alas, myth and fiction may occasionally overlap.

Sources are king

[edit]Ultimately, it is not up to the editor to determine whether something is fictional or mythical. It is up to the preponderance of reliable sources. If sources call something fictional or mythical, follow their lead. If the sources disagree, explain that disagreement, making sure to provide WP:DUE coverage of the respective arguments. That doesn't mean giving equal weight. If ten quality sources call it fictional, and one mythical, its probably wrong to call it mythical. But if six call it fictional and four call it mythical, then that needs to be clearly explained. It may also be best to avoid calling it one or the other in such a situation.

See also

[edit]Articles

[edit]Policies and guidelines

[edit]- Wikipedia:Neutral point of view/Religion – policy about how religious topics should take care to use words only in their formal senses to avoid causing unnecessary offence or misleading the reader.

- Wikipedia:What Wikipedia is Not § Wikipedia is not a soapbox – policy that covers faith-based arguments promotion/opposition.

- Wikipedia:Fringe theories – guideline that may cover some faith-based arguments against science, though not disputes between faiths.

- Wikipedia:Manual of Style/Contentious labels – guideline about recognizing and dealing with charged words.

Essays

[edit]- Wikipedia:Systemic bias – essay that covers faith-based bias in generally.

- 'Wikipedia:Academic bias – essay about how and why Wikipedia articles may have an academic (scholarly) bias.

- Wikipedia:Christian POV on Wikipedia – essay about how to preserve a neutral point of view about religion in articles.

- Wikipedia:Religion – failed policy proposal (2012)

Further reading

[edit]- Burke, Peter (2012). "History, Myth, and Fiction". The Oxford History of Historical Writing. Oxford University Press. p. 261–281. doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199219179.003.0014.

- Doty, William G. (1996). "Joseph Campbell's Myth and/Versus Religion". Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 79 (3/4). Penn State University Press: 421–445. ISSN 0038-1861. JSTOR 41178780.

- Dubois, Joel (2008). ""Myths, Stories & Reality"". California State University, Sacramento.