Douglas B-66 Destroyer

| B-66 Destroyer | |

|---|---|

A Douglas B-66B (53-506) in flight | |

| General information | |

| Type | Light bomber |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Douglas Aircraft Company |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Number built | 294[1] |

| History | |

| Introduction date | 1956 |

| First flight | 28 June 1954 |

| Retired | 1975[2] |

| Developed from | Douglas A-3 Skywarrior |

| Developed into | Northrop X-21 |

The Douglas B-66 Destroyer is a light bomber that was designed and produced by the American aviation manufacturer Douglas Aircraft Company.

The B-66 was developed for the United States Air Force (USAF) and is derivative of the United States Navy's A-3 Skywarrior, a heavy carrier-based attack aircraft. Officials intended for the aircraft to be a simple development of the earlier A-3, taking advantage of being strictly land-based to dispense with unnecessary naval features. Due to the USAF producing extensive and substantially divergent requirements, it became necessary to make considerable alterations to the design, leading to a substantial proportion of the B-66 being original. The B-66 retained the three-man crew arrangement of the US Navy's A-3; differences included the incorporation of ejection seats, which the A-3 had lacked.

Performing its maiden flight on 28 June 1954, the aircraft was introduced to USAF service during 1956. The standard model, designated B-66, was a bomber model that was procured to replace the aging Douglas A-26 Invader; in parallel, a photo reconnaissance model, the RB-66, was also produced alongside. Further variants of the type were developed, leading to the aircraft's use in signals intelligence, electronic countermeasures, radio relay, and weather reconnaissance operations.

Aircraft were commonly forward deployed to bases in Europe, where they could more easily approach the airspace of the Soviet Union. Multiple variants were deployed around Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis. They flew in the Vietnam War, typically operating as support aircraft for other aircraft that were active over the skies of North Vietnam and Laos, as well as missions to map SAM and AAA sites in both countries. The last examples of the type were withdrawn during 1975.

Design and development

[edit]Background

[edit]When the A-3 Skywarrior was in development for United States Navy, the project attracted attention from senior officers of the United States Air Force (USAF), who were skeptical regarding claims made about the design's specifications and capabilities. In particular, the USAF questioned its reported take-off weight of 68,000lb, suggesting that it would be impossible to achieve.[3] USAF general Hoyt Vandenberg ridiculed the proposed A-3 as "making irresponsible claims".[4] It has been suggested that this was a part of opposition within the USAF to the Navy's proposed "supercarriers": the United States-class, which would have carried the A-3, amongst other aircraft.[5]

While the supercarrier project did not proceed,[5] flight testing of the A-3 validated its performance. It was recognized that the type was capable of carrying out mission profiles practically identical to that of the much larger Boeing B-47 Stratojet, operated by the USAF. This included an unrefuelled combat radius of almost 1,000 miles. This performance, coupled with the fact of development costs having already been paid by the Navy, as well as pressing needs highlighted by the Korean War, made the A-3 attractive to the USAF.[3] Consequently, during the early 1950s, the USAF began to express interest in procuring a land-based variant.[3]

Redesign

[edit]USAF officials had originally intended the conversion to be a relatively straightforward matter of removing the carrier-specific features and fitting USAF avionics, but otherwise adhering as closely as possible to the original A-3 design.[3] For this reason, no prototypes were ordered when the USAF issued its contract to Douglas in June 1952, instead having opted for five pre-production RB-66A models to be supplied, the aerial reconnaissance mission being considered to be a high priority for the type. This contract was amended, involving multiple new variants that were added and swapped about.[3] Likewise, the list of modifications sought quickly expanded. To meet the changing requirements, the supposedly easy conversion became what was essentially an entirely new aircraft.[3]

A percentage of the changes made were a result of the USAF's requirement for the B-66 to perform low-level operations, the complete opposite of the US Navy's A-3, which had been developed and operated as a high-altitude nuclear strike bomber. However, aviation authors Bill Gunston and Peter Gilchrist attribute many of the design changes to have been made "merely to be different", being driven by an intense rivalry between the two services. They conclude that "an objective assessment might conclude that 98 per cent of the changes introduced in the RB-66A were unnecessary".[6] Both the fuselage and wing were entirely redesigned from scratch, rather than simply de-navalised.[7] The A-3 was powered by a pair of Pratt & Whitney J57 turbojet engines, whereas the B-66 used two Allison J71 engines. Gunston and Gilchrist note that this engine swap "offered no apparent advantage", generating less thrust and being more fuel-hungry than the J57 engine which was already in USAF use.[7]

Due to the engine change, this necessitated a complete redesign of the power systems as well, repositioning all hydraulic pumps and generators onto the engines themselves instead of being fed with bleed air from within the fuselage.[7] The pressurized crew compartment was given a different structure, adopting a very deep glazed front position for the pilot. The landing gear was redesigned, even implementing a completely different door geometry.[8] An impactful difference was the decision to equip the B-66 with ejection seats, a feature which the A-3 had lacked entirely.[7] Gunston and Gilchrist observe of the B-66 that: "The history of the aviation is sprinkled with aircraft which, to save money, were intended to be merely a modified version of an existing type. In very few cases it actually happened like this... the B-66 is a classic example".[3]

Into flight

[edit]On 28 June 1954, the first of the RB-66A pre-production aircraft conducted its maiden flight, development being only slightly behind schedule despite the substantial redesign work involved.[9] The test program, conducted with the five pre-production aircraft, heavily contributed to improvements in the production aircraft. On 4 January 1955, the first production B-66B aircraft, which featured an increased gross weight and numerous other refinements, performed its first flight.[9] Deliveries of the B-66B began on 16 March 1956. However, the USAF decided to curtail the bomber variant's procurement, cancelling a further 69 B-66Bs and largely relegating the model for use in various test programs.[9]

Once in service, the aircraft's design proved to be relatively versatile. The principal production model was the RB-66B, which incorporated the bomber version's upgrades.[9] It was either produced or retrofitted into a variety of other versions, including the EB-66, RB-66, and the WB-66. Likewise, many variants of the US Navy's A-3 Skywarrior were also produced.

Operational history

[edit]

In 1956, deliveries to the USAF began. A total of 145 RB-66Bs were produced. In service, the RB-66 functioned as the primary night photo-reconnaissance aircraft of the USAF during this period. Accordingly, many examples served with tactical reconnaissance squadrons based overseas, typically being stationed in the United Kingdom and West Germany. In November 1957, 9 B-66s were flown from California to the Philippines during Operation Mobile Zebra, but only 3 managed to make it all the way; the others didn't make it due to missing tanker rendezvous or mechanical problems.[10] A total of 72 of the B-66B bomber version were built, 69 fewer aircraft than had been originally planned.

A total of 13 B-66B aircraft later were modified into EB-66B electronic countermeasures (ECM) aircraft, which played a forward role in the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. They were stationed at RAF Chelveston with the 42nd Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron, who performed the conversion during the early 1960s. They rotated out of an alert pad in France during the time that the 42nd had them.

These aircraft, along with the RB-66Cs that the 42nd received, saw combat service during the Vietnam War. Unlike the US Navy's A-3 Skywarrior, which performed bombing missions in the theatre, the Destroyer did not perform bombing missions in Vietnam.[citation needed]

The RB-66C was a specialized electronic reconnaissance and electronic countermeasures (ECM) aircraft. According to Gunston and Gilchrist, it was the first aircraft designed from the onset for electronic intelligence (ELINT) missions.[2] It was operated by an expanded crew of seven, which included the additional electronics warfare specialists. A total of 36 of these aircraft were constructed. The additional crew members were housed in the space that was used to accommodate the camera/bomb bay of other variants. These aircraft were outfitted with distinctive wingtip pods that accommodated various receiver antennas, which were also present upon a belly-mounted blister.[2] Several RB-66Cs were operated in the vicinity of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis. They were also deployed over Vietnam. During 1966, these planes were re-designated as EB-66C.

Unarmed EB-66B, EB-66C and EB-66E aircraft flew numerous missions during the Vietnam War. They helped gather electronic intelligence about North Vietnamese defenses, and provided protection for bombing missions of the Republic F-105 Thunderchiefs by jamming North Vietnamese radar systems. Early on, B-66s flew oval "racetrack" patterns over North Vietnam, but after one B-66 was shot down by a MiG, the vulnerable flights were ordered to fly just outside North Vietnamese air space.[citation needed]

On 10 March 1964, a 19th TRS RB-66C flying on a photo-reconnaissance mission from the Toul-Rosières Air Base in France, was shot down over East Germany by a Soviet Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 after it had crossed over the border due to a compass malfunction. The crew ejected from the aircraft and, following a brief period of detention, were repatriated to the United States.[11]

The final Douglas B-66 variant was the WB-66D weather reconnaissance aircraft. 36 were built.[citation needed]

By 1975, the last EB-66C/E aircraft had been withdrawn from USAF service. Most aircraft were scrapped in place, others were temporarily stored while awaiting eventual scrapping.[citation needed]

Variants

[edit]- RB-66A

- (Douglas Model 1326) All-weather photo-reconnaissance variant, five built.

- RB-66B

- (Douglas Model 1329) Variant of the RB-66A with production J71-A-13 engines and higher gross weight, 149 built.

- B-66B

- (Douglas Model 1327A) Tactical bomber variant of the RB-66B, 72 built.

- NB-66B

- One B-66B used for testing and a RB-66B used for F-111 radar trials.

- RB-66C

- Electronic reconnaissance variant of the RB-66B, included an additional compartment for four equipment operators, 36 built.

- EB-66C

- Four RB-66Cs with uprated electronic countermeasures equipment.

- WB-66D

- Electronic weather reconnaissance variant with the crew compartment modified for two observers, 36 built with two later modified to X-21A.

- EB-66E

- Specialized electronic reconnaissance conversion of the B-66B.

Northrop X-21

[edit]

The Northrop X-21 was a modified WB-66D with an experimental wing, designed to conduct laminar flow control studies. Laminar-flow control was thought to potentially reduce drag by as much as 25%. Control would be by removal of a small amount of the boundary-layer air by suction through porous materials, multiple narrow surface slots, or small perforations. Northrop began flight research in April 1963 at Edwards Air Force Base, but with all of the problems encountered, and money going into the war, the X-21 was the last experiment involving this concept.[12]

Operators

[edit]- Spangdahlem Air Base, West Germany, 1957-59

- RAF Alconbury, England 1959-66

- 9th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (RB/WB-66)

- Shaw Air Force Base, South Carolina 1956-66

- 12th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (RB-66)

- Yokota Air Base, Japan 1956-60

- 19th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (EB/RB-66)

- RAF Sculthorpe, UK 1956-59

- Spangdahlem Air Base, West Germany 1959

- RAF Bruntingthorpe, UK 1959-62

- Toul-Rosieres Air Base, France 1962-65

- Chambley-Bussieres Air Base, France 1965-66

- Shaw AFB, South Carolina 1966-67

- 19th Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron (EB/RB-66)

- Shaw AFB, South Carolina 1967-68

- Itazuke Air Base, Japan 1968-69

- Kadena Air Base, Japan 1969-70

- 30th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (RB-66C)

- Sembach Air Base, West Germany 1957-58

- 39th Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron EB-66E/RB-66C

- Spangdahlem AB, Germany 1969-72

- 39th Tactical Electronic Warfare Training Squadron (EB/RB-66)

- Shaw AFB, South Carolina 1969-74

- 41st Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (EB/RB-66)

- Shaw AFB, South Carolina 1956-59

- Takhli Air Base, Thailand 1965-67

- 41st Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron (EB/RB-66)

- Takhli Air Base, Thailand 1967-69

- 42d Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (B/EB/RB/WB-66)

- Spangdahlem Air Base, West Germany 1956-59

- RAF Chelveston, UK 1959-62

- Toul-Rosieres Air Base, France 1962-63

- Chambley-Bussieres Air Base, France 1963-66

- 42d Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron (EB/RB-66)

- Takhli Air Base, Thailand 1968-70

- Korat Air Base, Thailand 1970-74

- 43d Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (RB-66)

- Shaw AFB, South Carolina 1956-59

- 4411th Combat Crew Training Group (B/EB/RB/WB-66)

- Shaw AFB, South Carolina 1959-66

- 4416th Test Squadron (EB/RB-66)

- Shaw AFB, South Carolina 1963-70

- 4417th Combat Crew Training Squadron (EB/RB-66)

- Shaw AFB, South Carolina 1966-69

Aircraft on display

[edit]

- RB-66B

- 53-0466 – Dyess Linear Air Park, Dyess AFB, Texas.[citation needed]

- 53-0475 – National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio[13]

- RB-66C

- 54-0465 – Shaw AFB, South Carolina.[citation needed]

- WB-66D

- 55-0390 – USAF Airman Heritage Museum at Lackland AFB, Texas.[citation needed]

- 55-0392 – Museum of Aviation, Robins AFB, Georgia[14]

- 55-0395 – Pima Air and Space Museum, adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson, Arizona[15]

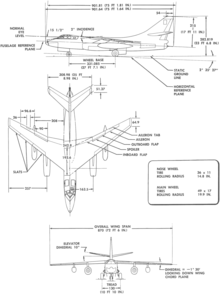

Specifications (B-66B)

[edit]

Data from McDonnell Douglas aircraft since 1920 : Volume I[16]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3 (Pilot, Navigator and EWO)

- Length: 75 ft 2 in (22.91 m)

- Wingspan: 72 ft 6 in (22.10 m)

- Height: 23 ft 7 in (7.19 m)

- Wing area: 780 sq ft (72 m2)

- Empty weight: 42,549 lb (19,300 kg)

- Gross weight: 57,800 lb (26,218 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 83,000 lb (37,648 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Allison J71-A-11 (later Allison J71-A-13) turbojet engines, 10,200 lbf (45 kN) thrust each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 548 kn (631 mph, 1,015 km/h) at 6,000 ft (1,800 m)

- Cruise speed: 459 kn (528 mph, 850 km/h)

- Combat range: 782 nmi (900 mi, 1,448 km)

- Ferry range: 2,146 nmi (2,470 mi, 3,974 km)

- Service ceiling: 39,400 ft (12,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 5,000 ft/min (25 m/s)

- Wing loading: 74.1 lb/sq ft (362 kg/m2)

Armament

- Guns: 2 × 20 mm M24 cannon in radar-controlled/remotely operated tail turret

- Bombs: 15,000 lb (6,800 kg)

Avionics

- APS-27 and K-5 radars

Notable appearances in media

[edit]The shooting down of an EB-66 over North Vietnam and the subsequent rescue of one of its crew became the subject for the book Bat*21 by William Charles Anderson, and later a film version (1988) starring Gene Hackman and Danny Glover.

See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Douglas B-66 Destroyer." Archived November 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved: 5 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Gunston and Gilchrist 1993, p. 164.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gunston and Gilchrist 1993, p. 161.

- ^ Gunston and Gilchrist 1993, p. 129.

- ^ a b Gunston and Gilchrist 1993, p. 128.

- ^ Gunston and Gilchrist 1993, pp. 161-162.

- ^ a b c d Gunston and Gilchrist 1993, p. 162.

- ^ Gunston and Gilchrist 1993, pp. 162-163.

- ^ a b c d Gunston and Gilchrist 1993, p. 163.

- ^ "Cold War Airpower Laboratory". 20 January 2017.

- ^ "SOVIET RELEASES INJURED CREWMAN OF DOWNED RB-66; Detains 2 Other Americans —Reply to U. S. Protest Vague on Trial Threat". The New York Times. New York City. 22 March 1964. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "B-66 Information." Archived 14 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine B66.info, Retrieved: 5 August 2010.

- ^ "Douglas RB-66B Destroyer." National Museum of the US Air Force, Retrieved: 24 August 2015.

- ^ "B-66 Destroyer/55-0392." Museum of Aviation, Retrieved: 18 December 2017.

- ^ "B-66 Destroyer/55-0395." Archived 2015-04-03 at the Wayback Machine Pima Air & Space Museum, Retrieved: 4 June 2015.

- ^ Francillon, René J. (1988). McDonnell Douglas aircraft since 1920 : Volume I. London: Naval Institute Press. pp. 498–505. ISBN 0870214284.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baugher, Joe. "Douglas B-66 Destroyer." USAAC/USAAF/USAF Bomber Aircraft: Third Series of USAAC/USAAF/USAF Bombers, 2001. Retrieved: 27 July 2006.

- Donald, David and Jon Lake, eds. Encyclopedia of World Military Aircraft. London: AIRtime Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-880588-24-2.

- Gunston, Bill and Peter Gilchrist. Jet Bombers: From the Messerschmitt Me 262 to the Stealth B-2. Osprey, 1993. ISBN 1-85532-258-7.

- "Douglas RB-66B 'Destroyer'." National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved: 27 July 2006.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. "Douglas A-3 Skywarrior." Military Aircraft of the Cold War (The Aviation Factfile). London: Grange Books plc, 2006. ISBN 1-84013-929-3.