Urapmin people

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (June 2020) |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| about 375 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Urapmin language | |

| Religion | |

| Baptist[1] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Telefol people, Tifal people |

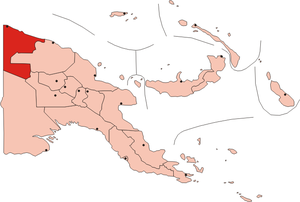

The Urapmin people are an ethnic group numbering about 375 people in the Telefomin District of the West Sepik Province of Papua New Guinea. One of the Min peoples who inhabit this area, the Urapmin share the common Min practices of hunter-gatherer subsistence, taro cultivation, and formerly, an elaborate secret cult available only to initiated men.

The Urapmin used to ally with the Telefolmin in war against other Min peoples, practicing cannibalism against the enemy dead, but warfare ceased by the 1960s with the arrival of colonialism. A Christian revival in the 1970s led to the near-complete abandonment of traditional beliefs and the adoption of a form of Charismatic Christianity originally derived from Baptist Christianity. The Urapmin vigorously use their native Urap language, and their small community maintains the practice of endogamy.

Classification

[edit]

The Urapmin are one of the Min peoples, a group of related peoples in Papua New Guinea who number about thirty thousand in total.[2][3][4] Min peoples are mainly found in the Telefomin District, spread from the mountains of the Strickland River to West Papua Province.[5][6] The name Min derives from the suffix -min, meaning 'peoples', which is present in their names (e.g. Telefolmin, Wopkaimin, etc.).[4]

Min peoples may also be known as Mountain Ok peoples, from the word ok meaning 'river' or 'water'.[4] The latter name contrasts them with the Lowland Ok people to the south who speak related languages but differ greatly culturally and in the environment that they live in.[4]

The Urapmin speak a Mountain Ok language.[2] Although this language family is tied to the Min ethnic grouping, it does not absolutely define the group, since the Oksapmin to the east and the Om river groups speak non-Mountain Ok languages.[7] The Urapmin kinship system is cognatic;[8] in general the western Min groups have bilateral kinship systems, while the eastern Min groups have patrilineal kinship systems.[7]

The Min peoples are fairly homogeneous in technology, economy, and subsistence.[7] This includes hunting and gathering from forests and stream-beds, shifting taro cultivation, and raising small numbers of domestic pigs.[7] Min material culture is also fairly uniform; Telefol women describe bilums throughout the Min region as being of "one kind", though there is some stylistic variation.[9]

A salient shared feature of Min culture is a common origin myth and initiation into a secret male religious cult.[6][7] Traditionally, the Min believed that all Min peoples other than the Baktaman are children of Afek, the "Primal Mother" and originator of all Min culture and religion.[10] The types and number of cult initiation ceremonies differed among different Min groups.[10] The Telefol in particular were viewed as being guardians of Afek's legacy since they were her lastborn,[9] and the Urapmin were close to the Telefol in the Min ritual hierarchy.[11]

History

[edit]

Historically, the Min peoples were in a constant state of warfare with one another.[12] Each Min tribe was a unified group whose component groups did not wage war among each other, with the exception of the Tifalmin people who were split into four mutually hostile groups.[12] The primary weapon used in war was a bow of black palm wood, usually using arrows with barbed wooden heads.[12]

Spears were unknown, though some tribes (e.g. the Telefolmin, but not the Tifalmin) used wooden clubs.[12] Warfare might consist either of small ambush parties, which would surprise people on paths and in gardens and kill and eat all of those caught, no matter their age or sex.[12] Other times, warfare was more formal, with groups marching out to meet each other for battle with freshly-painted shields.[12]

The Urapmin divided up peoples encountered into traditional allies (Urap: dup) and enemies (wasi), along with foreigners (ananang).[13] The Urapmin were allied with the Telefolmin, and engaged in trade with them, and in war joined with them to become a single unit.[14][15] This was based in the belief in descent from common ancestors.[12] The Urapmin also were friendly with their southern neighbors, the Faiwolmin.[12]

Friendly relations with foreign groups were based on trade—the Urapmin practiced a custom whereby men would have tisol dup (literally "wealth friend"), trading partners from other Mountain Ok groups.[16] The Telefol and Urapmin were traditionally enemies with the Tifalmin to the northwest and the Feranmin to the southeast.[7] Warfare was still practiced between the Min peoples in the first half of the twentieth century.[12]

European contact

[edit]European contact came late to Papua New Guinea, and to the Highlands in particular.[17] While the European contact with the Telefolmin dates to 1914, the earliest European contact with the Urapmin was made by the Williams party of 1936–1937, which was searching the Fly and Sepik areas for mineral deposits.[18] Led by an American by the name of Ward Williams, the party consisted of eight (later nine) Europeans and twenty-three natives recruited from the coast.[18] The Williams group had minimal contact with the Urapmin.[19]

Urapmin who were alive at the time attest that the Urapmin, unsure how to refer to the newcomers, learned from the Telefolmin to refer to them as the Wilumin, a portmanteau of the name 'William' and the suffix used for demonyms among the Min peoples, -min.[19][nb 1] A trade relationship was quickly established, with salt being the most desired commodity among the Urapmin.[16] The Urapmin relate that:

We were afraid when we first saw whites, but they enticed us with salt. We tasted it and it was good. And then they gave us matches and showed us how to make fires. Then we went and got them food, sweet potato, taro, and bananas and we gave it to them. We exchanged.[20]

In 1944, the Australians built up the airstrip in Telefomin for use by the Allied Forces as an emergency landing strip in the New Guinea campaign of World War II.[21] From this point until the end of the war, the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit kept a post in Telefomin, though it is unclear to what extent this affected the Urapmin at the time.[21] In 1948, after the conclusion of the war, a patrol station was established at Telefomin, marking the beginning of Australian colonization of the region.[21]

The Urapmin refer to the subsequent colonial period as the time when "the law came and got us" (Tok Pisin: lo i kam kisim mipela) or when "we got the law" (Tok Pisin: mipela kisim lo).[22]

What was likely the first government patrol of the Urapmin area was conducted in 1949 by Patrol Officer J. R. Rogers, accompanied by nine native policemen.[23] Rogers convinced the Urapmin to make peace with the Tifalmin, stating that "fighting and cannibalism must cease."[23] The Urapmin performed a tisol dalamin ("equivalent exchange ceremony"), a traditional form of dispute resolution which had not been used before by the Urapmin to make peace with enemy peoples.[23]

By the 60s the majority of the Telefomin region had been pacified.[12] Large numbers of Urapmin converted to Christianity between the mid-1960s and the mid-1970s.[24] The religion was brought to Urapmin by Telefol and Urapmin pastors who had studied in Telefomin at the Australian Baptist Mission.[24] While Urapmin never hosted expatriate missionaries, by the mid-1970s there were a number of knowledgeable Christians in the community.[24] However, the majority of conversions occurred during a Christian revival which swept the New Guinea Highlands in the late 1970s.[25] The rebaibal, as it is known in Tok Pisin, had begun in the Solomon Islands and reached Urapmin by 1977.[24] This movement caused all of the Urapmin to convert, and led to the rise of Charismatic Christianity among the Urapmin.[24][25]

Urapmin society has been significantly affected by the Ok Tedi mine.[26] The mine is located in Tabubil, built in the early 1980s, which is located two-and-a-half days by foot from Urapmin, or accessible by plane from Telefomin.[24] By the early 1990s, many Urapmin had begun visiting Tabubil once every few years, more frequently for prominent families.[24] For the Urapmin, Tabubil has become both a place where consumer goods are visible and a haven from sharing resources.[24]

Few Urapmin have been employed by the mine at any time, and due to the lack of a road or airstrip, the Urapmin have been unable to market vegetables to the mine as have their neighbors.[27] As a result, the Urapmin have not experienced much of the economic development that has occurred to neighboring groups.[27] The Kennecott company began prospecting for gold on Urapmin land in 1989, raising hopes, and while the company left Papua New Guinea in 1992, the Urapmin remain optimistic about future prospecting.[27]

Geography

[edit]

The Urapmin number about 375, living in the Telefomin District in West Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea.[5][28] Along with the more-numerous Telefol people, they are located by the headwaters of the Sepik River, the Telefomin Valley, and the nearby Elliptaman Valley.[29] They live in a remote region; Telefomin, the District Office, and an airstrip can only be reached by a difficult seventeen-mile walk.[28]

The total area of Urapmin territory is small, and most villages are within walking distance.[30] Most of the Urapmin villages (Urap: abiip) are located along the top of a ridge in the foothills of the Behrmann mountains.[31] The ridge is known in Urap as Bimbel, named after the earthquake spirit Bim who is believed to have flattened out the ridge.[31][nb 2] The villages along the Bimbel ridge are Danbel (Muli Kona), Salafaltigin, Drum Tem, Atemkit, and Dimidubiip.[31]

There are also two villages known as "places at the sides" (Tok Pisin: saitsait ples) which are near the ridge but not directly on top of it; these are Makalbel and Ayendubiip.[31] Urapmin from the more northerly villages of Atemkit, Dimidubiip, and Ayendubiip are known as "bottom" Urapmin, while the others are known as "top" Urapmin.[30]

Culture

[edit]As with other remote Papuan groups, the central elements of Urapmin life are subsistence agriculture, hunting, and Christianity.[28]

Language

[edit]The native language of the Urapmin is known as the Urapmin or Urap language (Urap: urap weng), a member of the Mountain Ok subfamily of the Ok languages.[32] Although Urap is linguistically intermediate between its geographic neighbors Telefol and Tifal, it is not a dialect of either.[32][33] Multilingualism among the Urapmin has led many Telefolmin to believe that the Urapmin speak Telefol among themselves, but this is not the case.[32] Although the Urapmin view the Tifal language as being closer to Urap than the Telefol language is, and an early account claimed that the Urapmin speak Tifal, more recent research indicates that they should not be considered the same language.[32] Urap remains in vigorous use among the Urapmin, and is the main language that they use.[34]

One unusual feature of the Urapmin language is the use of dyadic kinship terms.[35] These terms translate into English as reciprocal kinship or affinity relations such as "(pair of) brothers" or "father and child", and may sometimes even refer to a relations between three or more people.[36] These terms can encode relative age, kinship or affinity, number of members, and gender.[36] For example, a pair of siblings is alep (plural ningkil), a pair of affines is kasamdim (plural amdimal), a couple is agam (plural akmal), a woman with a child is awat (plural aptil), and a man with a child is alim (plural alimal).[36][nb 3]

The plural forms are not marked for which generation is pluralized; thus alimal may either mean (a) one man and two children or (b) one man, one woman, and one child.[36] These terms are used to address groups, but not single individuals, so for example a mother of two children would never to referred to or addressed using the term aptil (rather, one would use alamon 'mother').[36] However, a pastor could address his congregation—a collection of husbands and their wives and children—as sios alimal 'church alimal' or just alimal.[37]

The Tok Pisin language is also widely used by the Urapmin.[32] One of the national languages of Papua New Guinea, Tok Pisin is an important lingua franca in rural areas.[32] The Urapmin learn the language from older children and in school, becoming fluent around the age of twelve.[32][nb 4] Tok Pisin is regularly used in daily life, and has contributed many loan words to Urap.[34] In particular, Tok Pisin is associated with modernity and Western institutions and is regularly used in contexts such as local governance and Christian services and discussions.[34] Unlike some other peoples in Papua New Guinea, the Urapmin have not attempted to find native equivalents for Tok Pisin terms related to Christianity.[34] The New Testament edition most used by the Urapmin is in Tok Pisin, the Nupela Testamen Ol Sam published by the Bible Society of Papua New Guinea.[38]

Economic system

[edit]

The Urapmin practice slash-and-burn agriculture, and raise small numbers of pigs.[3] The main source of sustenance for the Urapmin is taro (Urap: ima) and sweet potato (Urap: wan), grown in swidden gardens (Urap: lang) in the bush.[8] In fact the main word for "food" in Urap is formed by compounding these two nouns.[39] These are supplemented by banana, pandanus, sugar cane, and various other cultigens.[27]

The hunting of marsupials, wild pigs, and other game is greatly valued in Urapmin culture, but it does not contribute significantly to sustenance.[3] Domestic pigs are raised in only small numbers and killed on special occasions.[27] Tinned fish, rice, and frozen chicken must be brought in from Telefomin, the District Office, or Tabubil, and are considered by the Urapmin to be luxury goods.[27]

As with many other Papuan groups, the Urapmin consider the owner of an object or land to be the first person to create or work it.[40] This is taken to the extent that every object in a household is considered to have an owner, and some households have even divided their shared gardens into individually owned plots.[40] According to the traditional beliefs of the Urapmin, this fits into a general worldview where everything had an owner, either human or spirit.[40]

Religion

[edit]The Urapmin stand out among "remote" hunter-gatherer societies in how strongly they have rejected their traditional beliefs and practices (Urap: alowal imi kukup, literally "ways of the ancestors") and embraced those of Protestant Christianity.[25] Unlike in other Papuan cultures, among the Urapmin there is no ongoing conflict between Christians (Tok Pisin: kristins) and "heathens" (Tok Pisin: haidens).[41] Some rituals are still subjects of debate among the Urapmin as to whether they should still be practiced, in particular pig sacrifice and bridewealth exchange.[42]

Traditional beliefs

[edit]According to traditional Urapmin belief, all beings which existed in the world before the creation of humans were spirits.[43] Humans were created in a multiple birth of the cultural heroine Afek, emerging immediately after the first dog (Urap: kyam).[43] Afek gave the bush to the spirits right before birthing humans so that they would clear out the villages for the humans to dwell in.[43] Since as such dogs are spirits, and as the Urapmin say the "older brother" of man, the Urapmin do not kill or eat them, unlike some neighboring tribes, nor do they let dogs breathe on their food[43] (this contrasts with humans—the Urapmin previously had no cannibalism taboo, and they may share food with them[clarification needed]).[43] In fact, the taboo on eating dogs is one of the few still widely observed.[44]

Afek was viewed both as the physical mother of all Min peoples other than the Baktaman, and as the originator of all Min culture and religion.[10] The Telefol, as the lastborn of Afek, were thus entrusted with the guardianship of her legacy[9] (the Urapmin were at or at least quite close to the level of the Telefol in this hierarchy of religious knowledge).[45] The Min peoples believed Afek to have left her primary relics in the cult house in the village of Telefolip (a contraction of Telefol abiip 'village of the Telefol').[9] Afek was believed to have married a serpent who formed the glade that only men could enter to reach Telefolip upon its death throes.[46] Telefolip was never moved, and the buildings in Telefolip would constantly be rebuilt on the same locations.[9]

The traditional law of the Urapmin was characterized by many rules about religious behavior and an elaborate taboo system, focused especially on eating and land use, as well as regulating what could be touched and who could know what information.[47][48] According to Urapmin tradition, Afek gave ownership of the wild (sep) to the motobil (nature spirits), who themselves gave ownership of the villages (abiip) to humans.[40] Natural resources, including streams, large trees, hunting ground, and game were believed to be owned by the motobil, and humans could only use what they were given permission to respectfully.[40]

Violation of these rules was thought to cause illness.[40] This system of taboos, known as awem in the Urapmin language, was well-developed and shaped everyday life.[48] Those who became ill due to disrespecting the land or animals of the motobil would pray for the spirits to "unhand" them, or if this did not work they would sacrifice pigs in order to appease the spirits.[3][40] Recently, the Urapmin required gold prospectors to sacrifice to these spirits before digging on their land, although this pre-emptive use of sacrifice is new to the Urapmin.[3]

Awem was abandoned in the late 1970s once the community had transitioned to Christianity, which was understood to be opposed to the practice of taboo.[49] The Urapmin refer to the current period as "free time" (Tok Pisin: fri taim), a liberating era where food and ground are freely available.[49] However, while the Urapmin now believe that God rather than Afek created everything, they still believe in the existence of motobil, albeit as "bad spirits" (Urap: sinik mafak).[41][50]

They now believe that Afek and the other mythical Urapmin characters arose after the generations of "Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah and Abraham" and lied, claiming falsely that they had created everything and that breaking their taboos would induce illness.[51] Since the Urapmin now believe that God gave creation to humans to use, they see taking the motobils' property to be a moral imperative.[50] However, the Urapmin still believe in motobil-induced illness, and therefore they do occasionally sacrifice to the motobil, despite this being against Christian teachings.[50]

The Urapmin still abide by a traditional ethical code which requires mutual support (Urapmin: dangdagalin) and forbidden social actions (Urapmin: awem, but distinct from the other form of awem), including adultery, anger, fighting, and theft.[48] As in many other Melanesian societies, one who eats alone (Urapmin: feg inin) is condemned, for a person should share his food with others (Urapmin: sigil).[48] Ethical breaches could be fixed by rituals such as "buying the anger" (Urapmin: aget atul sanin), "buying the shame" (fitom sanin), and these are still practiced today.[52] The Urapmin also used to ritually remove anger from the body in order to prevent disease, but this has now been replaced by prayer for God to remove one's anger.[52]

The Urapmin used to practice a type of male initiation known in Urap as ban.[42] These elaborate rituals, for which the Min peoples are famous, were a central part of Urapmin social life.[53] The ban was a multistage process which involved beatings and manipulation of various objects.[42] At each stage, the initiate was offered revelations of secret knowledge (Urap: weng awem), but at the next stage these would be shown to be false (Urap: famoul).[42] These initiations have been abandoned with the adoption of Christianity, and the Urap have expressed relief at no longer having to administer the beatings which were involved.[49]

Christianity

[edit]Due to the rise of Charismatic Christianity among the Urapmin, by the early 1990s, Urapmin Christianity was characterized by "healing, possession, constant prayer, confession, and frequent, lengthy church services."[24] As elsewhere in Papua New Guinea, the form of Christianity among the Urapmin focuses especially on "millennial themes"—the return of Jesus and impending judgement.[54] In particular, the central themes of Urapmin Christianity are the last days (Tok Pisin: las de), meaning the imminent return of Jesus to take his followers to heaven, and the need to live an ethical Christian life (Tok Pisin: Kristin laip) in order to be one of those taken in the last days.[24]

Religious discourse often focuses on the need to control desires and obey the law of the Bible and the government in order to live a good Christian life.[24] These themes were traditionally important to the Urapmin even before the advent of Christianity.[24] Urapmin society recognizes an opposition between the character traits of willfulness (Urapmin: futabemin) and obeying the law (Urapmin: awem) or the demands of others (Urapmin weng sankamin, lit. "to hear speech").[55] Willfulness is defined as when one's will or desire (Urapmin: san, Tok Pisin: laik) causes one to ignore the demands of the law or other people.[55]

Both traits are considered important; for example, a woman is expected to choose her husband by exercising her own will, rather than caving to the pressure of her family or her suitors.[56][nb 5]

Many Melanesian societies recognize such an opposition; however, while in other societies balance between willfulness and respecting others' needs is achieved by community leaders or by dividing these traits between men and women, in Urapmin society each individual must balance these him or herself.[57] However, the adoption of Christianity led to a vilification of willful behavior in general, since salvation could only be reached by following God's will; therefore, the focus of Urapmin culture became the suppression of desire.[49]

The Urapmin have replaced traditional rituals with new, Christian methods for removing sin (Tok Pisin: sin, Urapmin yum, lit. debt).[47] The Urapmin have innovated an institution of confession (Tok Pisin: autim sin), which was not present in the Baptist Church which they belong to.[1][42] Confessions are held at least once a month, and some Urapmin keep lists of sins in order not to forget to confess them.[1] Pastors and other leaders regularly give haranguing lectures (Urapmin: weng kem) about avoiding sin.[1]

Another sin-removal ritual that the Urapmin practice is a form of group possession known as the "spirit disco" (Tok Pisin: spirit disko).[58] Men and women gather in church buildings, dancing in circles and jumping up and down while women sing Christian songs; this is called "pulling the [Holy] spirit" (Tok Pisin: pulim spirit, Urap: Sinik dagamin).[59][60] The songs' melodies are borrowed from traditional women's songs sung at drum dances (Urap: wat dalamin), and the lyrics are typically in Telefol or other Mountain Ok languages.[60] If successful, some dancers will "get the spirit" (Tok Pisin: kisim spirit), flailing wildly and careening about the dance floor.[59]

After an hour or more, those possessed will collapse, the singing will end, and the spirit disco will end with a prayer and, if there is time, a Bible reading and sermon.[59] The body is believed to normally be "heavy" (Urap: ilum) with sin, and possession is the process of the Holy Spirit throwing the sins from one's body, making the person "light" (Urap: fong) again.[59] This is a completely new ritual for the Urapmin, who have no indigenous tradition of spirit-possession.[61]

The Urapmin practice frequent prayer (Tok Pisin: beten), at least beginning and ending the day with prayer, and often praying a number of times throughout the day.[25] Prayer may be both communal and individual, for such things as health, agriculture, hunting, relief from anger, bad omens in dreams, blessing meals, removal of sin, and just to offer praise to God.[25] In addition to ritual speech during prayer, the Urapmin emphasize that a Christian life involves listening to "God's talk" (Urap: Gat ami weng).[42] The centrality of speech in modern Urapmin Christianity contrasts sharply with the mainly ritual-based traditional Urapmin culture, where sacred speech might even be blatantly false.[42] The Urapmin have a cliché that reflects this: "God is nothing but talk" (Urap: Gat ka weng katagup; Tok Pisin: Gat em i tok tasol).[42]

Kinship

[edit]The Urapmin practice endogamy.[8] Since the Urapmin community is quite small, numbering in the hundreds, and Urapmin do not marry first cousins, the result is that most Urapmin are related to each other relatively directly.[8]

The Urapmin are divided into kinship classes known as tanum miit (literally "man origin").[62] The five tanum miit currently in widespread use are the Awem Tem Kasel, the Awalik, the Atemkitmin, the Amtanmin, and the Kobrenmin.[62] There is also a Fetkiyakmin group which is dying out, and in the past there were other tanum miit which have already gone extinct.[62] The tanum miit used to be related to specific ritual observances and secret mythologies.[62] Supernatural powers were believed to be distributed among them; for example, one group controlled the wind and another the rain.[63] Currently, they are viewed as the largest landholding units, and each village is thought to have a dominant tanum miit.[62]

Tanum miit are inherited cognatically through both parents; so one person may be a member of four tanum miit at once just by considering his or her grandparents.[62][nb 6] Because of the close family connections between all of the Urapmin, any Urapmin can assert membership in every tanum miit and some can calculate how they have inherited them.[62] The tanum miit thus do little to differentiate people in Urapmin society, and their membership is "fluid".[8][62] However, the kamokim ('big men'), the more influential Urapmin, may treat these groups as more exclusive in order to organize others' actions.[62]

Political system

[edit]The Urapmin have a group of leaders, known as kamokim (singular kamok) in the Urapmin language and bikman in Tok Pisin.[53] These leaders organize people into villages, help people pay bridewealth payments, speak at court cases, and organize work groups to carry out large-scale projects.[53] The kamokim are held in high regard in all public spheres and are a common topic of conversation.[53]

The Urapmin make a division between the village (Urap: abiip) and the bush (Urap: sep).[64] These domains are kept separate, and the Urapmin keep their villages free of plant matter.[64] Villages are U-shaped with dirt-packed plazas, with no grass or weeds.[65] Most Urapmin have at least one house in a village (Urap: am).[8][56] However, due to the importance of forest gardens for sustenance, the Urapmin spend much of their time in isolated bush houses (Urap: sep am), built in elaborate fashion near gardens and hunting grounds.[8][56] Villages are arranged by the kamokim, who coax people from sep am or from other villages.[56] When the kamok dies, the village inhabitants disperse.[56]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Urapmin later abandoned this term and began calling the whites dalabal, meaning the smell of a penis gourd. Eventually the coastal natives that were hired by another patrol taught the Urapmin the term tabalasep, which is the term that is currently used in the Urap language for whites. See Robbins (2004:50).

- ^ The word for "earthquake" in Urap is also bim. See Robbins (2004:21)

- ^ Urapmin differs from Telefol in that it does not distinguish groups of siblings (ningkil) based on whether they are single or mixed sex groups. See Robbins (2004:348).

- ^ The language of schooling is nominally English, and use of Tok Pisin is officially forbidden. However, in effect students become literate in Tok Pisin, while never getting close to becoming fluent in English. See Robbins (2004:37).

- ^ The practice of following the woman's desire in marriage is known in Tok Pisin as laik bilong meri. Among many other Papuan groups, and in particular among the neighboring Telefomin, laik bilong meri is a new practice associated with the colonial government. However, among Urapmin it is believed to be an old custom of theirs, as authenticated by the elaborate ritual surrounding it and in their oral genealogical records. See Robbins (1998:314).

- ^ Tanum miit do not play a role in marriage, so a person may inherit less tanum miit from his or her grandparent if they share tanum miit. See Robbins (2004:191–192).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Robbins (1998:308)

- ^ a b Barker (2007:28)

- ^ a b c d e Moretti (2007:306)

- ^ a b c d MacKenzie (1991:31)

- ^ a b Cranstone (1968:609)

- ^ a b Brumbaugh (1980:332)

- ^ a b c d e f MacKenzie (1991:32)

- ^ a b c d e f g Robbins (2004:24)

- ^ a b c d e MacKenzie (1991:33)

- ^ a b c MacKenzie (1991:32–33)

- ^ Robbins (2004:15, 17)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cranstone (1968:610)

- ^ Robbins (2004:88)

- ^ Cranstone (1968:618)

- ^ Brumbaugh (1980:333)

- ^ a b Robbins (2004:51)

- ^ Robbins (2004:46)

- ^ a b Robbins (2004:49)

- ^ a b Robbins (2004:50)

- ^ Babalok, a member of the Urapmin, quoted in Robbins (2004:51)

- ^ a b c Robbins (2004:53)

- ^ Robbins (2004:47)

- ^ a b c Robbins (2004:54)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Robbins (1998:301)

- ^ a b c d e Robbins (2001:903)

- ^ Robbins (1998:300–301)

- ^ a b c d e f Robbins (1995:213)

- ^ a b c Robbins (1998:300)

- ^ Brumbaugh (1980:332–333)

- ^ a b Robbins (2004:22)

- ^ a b c d Robbins (2004:21)

- ^ a b c d e f g Robbins (2004:37)

- ^ "Urapmin". SIL International. n.d. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Robbins (2004:38)

- ^ Robbins (2004:300)

- ^ a b c d e Robbins (2004:301)

- ^ Robbins (2004:302)

- ^ Robbins (2004:39)

- ^ Robbins (1995:212–213)

- ^ a b c d e f g Moretti (2007:307)

- ^ a b Robbins (1995:214)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Robbins (2001:904)

- ^ a b c d e Robbins (2006:176–177)

- ^ Robbins (2006:177, 190)

- ^ Robbins (2004:17)

- ^ Cranstone (1968:620)

- ^ a b Robbins (1998:307)

- ^ a b c d Robbins (1998:305)

- ^ a b c d Robbins (1998:307–308)

- ^ a b c Moretti (2007:309)

- ^ Robbins (1995:216)

- ^ a b Robbins (1998:306, 310)

- ^ a b c d Barker (2007:29)

- ^ Robbins (1998:299)

- ^ a b Robbins (1998:303)

- ^ a b c d e Robbins (1998:304)

- ^ Robbins (1998:302)

- ^ Robbins (1998:310–311)

- ^ a b c d Robbins (1998:311)

- ^ a b Robbins (2004:284)

- ^ Robbins (1998:312)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Robbins (2004:191–192)

- ^ Robbins (2004:52)

- ^ a b Robbins (2006:176)

- ^ Robbins (2004:23)

Bibliography

[edit]- Barker, John (2007). The Anthropology of Morality in Melanesia and Beyond. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0754671855.

- Brumbaugh, Robert (1980). "Models of Separation and a Mountain Ok Religion". Ethos. 8 (4): 332–348. doi:10.1525/eth.1980.8.4.02a00050.

- Cranstone, B. (1968). "War shields of the Telefomin sub-district, New Guinea". Man. 3 (4): 609–624. doi:10.2307/2798582. JSTOR 2798582.

- MacKenzie, Maureen (1991). Androgynous Objects: String Bags and Gender in Central New Guinea. Routledge. ISBN 978-3718651559.

- Moretti, Daniele (2007). "Ecocosmologies in the Making: New Mining Rituals in Two Papua New Guinea Societies". Ethnology. 46 (4).

- Robbins, Joel (2006). "Properties of Nature, Properties of Culture: Ownership, Recognition, and the Politics of Nature in a Papua New Guinea Society". In Biersack, Aletta; Greenberg, James (eds.). Reimagining Political Ecology. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3672-3.

- Robbins, Joel (2004). Becoming Sinners: Christianity and Moral Torment in a Papua New Guinea Society. University of California Press. p. 383. ISBN 978-0-520-23800-8.

- Robbins, Joel (2001). "God Is Nothing but Talk: Modernity, Language, and Prayer in a Papua New Guinea Society". American Anthropologist. 103 (4): 901–912. doi:10.1525/aa.2001.103.4.901.

- Robbins, Joel (1998). "Becoming Sinners: Christianity and Desire among the Urapmin of Papua New Guinea". Ethnology. 37 (4): 299–316. doi:10.2307/3773784. JSTOR 3773784.

- Robbins, Joel (1995). "Dispossessing the Spirits: Christian Transformations of Desire and Ecology among the Urapmin of Papua New Guinea quick view". Ethnology. 34 (3): 211. doi:10.2307/3773824. JSTOR 3773824.