The Power of Sympathy

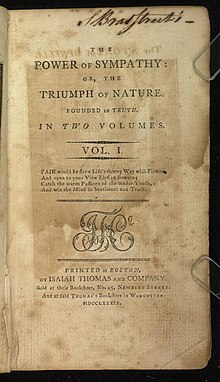

Title page of the first edition | |

| Author | William Hill Brown |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Sentimental novel |

| Publisher | Isaiah Thomas |

Publication date | January 21, 1789 |

| Publication place | United States |

The Power of Sympathy: or, The Triumph of Nature (1789) is an 18th-century American sentimental novel written in epistolary form by William Hill Brown and is widely considered to be the first American novel.[1] The Power of Sympathy was Brown's first novel. The characters' struggles illustrate the dangers of seduction and the pitfalls of giving in to one's passions, while advocating the moral education of women and the use of rational thinking as ways to prevent the consequences of such actions.

Characters

[edit]- Thomas Harrington

- Myra Harrington, sister to Thomas

- Harriot Fawcet, illegitimate sister to Thomas and Myra

- Jack Worthy

- Mrs. Eliza Holmes, common friend of the Harringtons and Harriot

- Mr. Harrington, Thomas and Myra's father

- Maria, Mr. Harrington's mistress and Harriot's mother

- Martin and Ophelia[who?]

Plot summary

[edit]The opening letters between Thomas Harrington and Jack Worthy reveal that Thomas has fallen for Harriot Fawcet, despite the reservations of his father. Harriot resists Thomas's initial advances, as he intends to make her his mistress; readers also find that Jack encourages Thomas to abandon his licentious motives in favor of properly courting Harriot. However, when Thomas and Harriot become engaged, Eliza Holmes becomes alarmed and exposes a deep family secret to Thomas's sister Myra: Harriot is in fact Thomas and Myra’s illegitimate half-sister. Mr. Harrington's one time affair with Maria Fawcet resulted in Harriot's birth, which had to be kept a secret to maintain the family’s honor. Thus, Eliza’s mother-in-law, the late Mrs. Holmes, took Maria, Thomas and Harriot into her home. After Maria’s death, Harriot was raised by a family friend, Mrs. Francis.

Upon receiving the news of this family secret, Harriot and Thomas are devastated, as their relationship is incestuous and thus forbidden. Harriot falls into a grief-stricken consumption (a condition now referred to as tuberculosis), from which she is unable to recover. Thomas spirals into a deep depression and commits suicide after learning of Harriot's death.

Subplot in historical context

[edit]A subplot in the novel mirrors a local New England scandal involving Brown's neighbor Perez Morton's seduction of Fanny Apthorp; Apthorp was Morton's sister-in-law. Apthorp became pregnant and committed suicide, but Morton was not legally punished.[2] The scandal was widely known,[3] so most readers were able to quickly identify the "real" story behind the fiction: "in every essential, Brown's story is an indictment of Morton and an exoneration of Fanny Apthorp",[4] with "Martin" and "Ophelia" representing Morton and Apthorp, respectively.

Publication history

[edit]The Power of Sympathy was first published by Isaiah Thomas in Boston on January 21, 1789,[5] and sold at the price of nine shillings.[6] The novel did not sell well.[7]

The novel was first published anonymously, but was popularly attributed to Boston poet Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton because of the resemblance between the plot and a scandal in her family; Brown was not correctly identified as the author until 1894.[8]

Critical discussions

[edit]The novel has ties to American politics and nationhood, just as many early American sentimental novels can be read as allegorical accounts of the nation's development.[9][page needed] These critics have argued that these novels' use of moral education as a means to avoid seduction functions as a way to show readers the virtues and education most needed by the new American nation. Elizabeth Maddock Dillon complicates this standard reading by locating the novel within a global context marked by "forces of colonialism, mercantile capitalism, and imperialism".[10] In this reading, the workings of the novel (incest and miscegenation specifically, Dillon argues) are read not necessarily as indicative of the formation of the American nation but as representative of the effects of colonialism in the New World.

As the novel's title indicates, sympathy is the driving force behind several characters' actions. The excesses of sympathetic thought lead to tragedy; it is implied that Harrington's suicide, for example, is spurred on by an over-identification with The Sorrows of Young Werther, a copy of which is found alongside his body.[11] These excesses are contrasted with the rational thinking of characters like Worthy, who strives to uphold normative social and moral ideals. While the overly sympathetic characters do not survive the course of the novel, the rational characters do survive, suggesting that at the very least, a balance of sympathy and rational thinking (or the use of reason to overcome passion) are necessary for a productive, successful member of society.[according to whom?]

Another scholarly discussion surrounding the text is the question of its ability to serve as a didactic text for 18th-century readers, with earlier critics unquestioningly discussing the novel's didactic intent;[12] more recent scholars, however, have questioned the novel's ability to teach morality yet frankly discuss seduction and incest. The novel's preface claims that it is:

Intended to represent the specious causes, and to Expose the fatal CONSEQUENCES, of SEDUCTION; To inspire the Female Mind With a Principle of Self Complacency, and to Promote the Economy of Human Life.

Brown claimed that the purpose of his text was to teach young women how to avoid scandalous errors. Although discussions of seduction and incest are included to illustrate their potential dangers, some scholars[who?] have asserted that these issues overshadow the morality lesson and argue that 18th-century readers read such novels for the thrill of taboo discussions, not moral guidance.[according to whom?]

Notes

[edit]- ^ For an extended discussion of the critical debate surrounding the claims to this title, see Cathy Davidson, Revolution and the Word (153–156) and Carla Mulford's introduction to the 1996 Penguin edition of the text, among other sources.

- ^ Davidson, Cathy. Revolution and the Word. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. p. 7.

- ^ Walser, Richard. "Boston's Reception of the First American Novel". Early American Literature 17(1): 65–74. p. 66.

- ^ Davidson, Cathy. Revolution and the Word. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. p. 175.

- ^ King, Steve (January 21, 2011). "Brown's Power of Sympathy". Barnes & Noble. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ The Power of Sympathy, bibliographical note Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Seelye, John (1988). "Charles Brockden Brown and Early American Fiction". In Elliott, Emory (ed.). Columbia Literary History of the United States. New York: Columbia UP. p. 172.

- ^ Gray, Richard (2004). A History of American Literature. Blackwell. p. 92.

- ^ For a few scholars' accounts of this linkage between novel and nation, see Jay Fliegelman, Prodigals and Pilgrims: The Revolution Against Patriarchal Authority and Elizabeth Barnes, States of Sympathy: Seduction and Democracy in the American Novel.

- ^ Dillon, Elizabeth Maddock. "The Original American Novel, or, The American Origin of the Novel". A Companion to the Eighteenth-Century English Novel and Culture. Eds. Paula Backscheider and Catherine Ingrassia. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005. 235–260. p. 235.

- ^ Brown, William Hill. The Power of Sympathy. New York: Penguin Books, 1996. p. 100.

- ^ Walser, Richard. "Boston's Reception of the First American Novel". Early American Literature 17(1): 65–74. p. 72.

References

[edit]- Brown, William Hill and Hannah Webster Foster. The Power of Sympathy and The Coquette. (Penguin Classics, 1996)

- Byers Jr., John R. A Letter of William Hill Brown's (in Notes). American Literature 49.4 (January 1978): 606–611.

- Ellis, Milton. The Author of the First American Novel. American Literature 4.4 (January 1933): 359–368.

- Lawson-Peebles, Robert. American Literature Before 1880. London: Pearson Education, 2003.

- Martin, Terrence. William Hill Brown's Ira and Isabella. The New England Quarterly 32.2 (June 1959): 238–242.

- Murrin, John M. et al. Liberty, Freedom, and Power: A History of the American People. Volume I., 4th ed. pp. 252–253. (Wadsworth, 2005)

- Shapiro, Steven. The Culture and Commerce of the Early American Novel: Reading the Atlantic-World System. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008.

- Walser, Richard. More About the First American Novel. American Literature 24.3 (November 1952): 352–357.

- Walser, Richard. The Fatal Effects of Seduction (1789) Modern Language Notes 69.8 (December 1954): 574–576.

External links

[edit]- The Power of Sympathy and The Coquette at the Internet Archive

The Power of Sympathy public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Power of Sympathy public domain audiobook at LibriVox