Bernardino of Siena

Saint Bernardino of Siena OFM | |

|---|---|

| |

| Priest, Confessor, Apostle of Italy | |

| Born | 8 September 1380 Massa Marittima, Republic of Siena, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 20 May 1444 (aged 63) Aquila, Kingdom of Naples, Holy Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 24 November 1449 |

| Canonized | 24 May 1450, Rome, Papal States by Pope Nicholas V |

| Feast | 20 May |

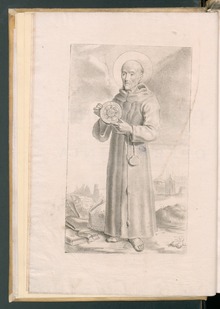

| Attributes | Tablet with IHS; three mitres representing the bishoprics which he refused |

| Patronage | Advertisers; advertising; Aquila, Italy; chest problems; Italy; Diocese of San Bernardino, California; gambling addicts; public relations personnel; public relations work; Bernalda, Italy; San Bernardino, Switzerland |

Bernardino of Siena, OFM (Bernardine or Bernadine;[1][2] 8 September 1380 – 20 May 1444), was an Italian Catholic priest and Franciscan missionary preacher in Italy. He was a systematizer of scholastic economics.

His preaching, his book burnings, and his "bonfires of the vanities" established his reputation in his own lifetime; they were frequently directed against gambling, infanticide, sorcery/witchcraft, sodomy (chiefly among homosexual males), Jews, Romani "Gypsies", usury, and the like.

Bernardino was canonised by Pope Nicholas V in 1450 and is referred to as "the Apostle of Italy" for his efforts to revive the country's Catholicism during the 15th century.[3]

Sources

[edit]Two hagiographies of Bernardino of Siena were written by two of his friends; the one the same year in which he died, by Barnaba of Siena; the other by the humanist Maffeo Vegio. Another important contemporary biographical source is that written by the Sienese diplomat Leonardo Benvoglienti, who was another personal acquaintance of Bernardino's.[4] The historian Franco Mormando notes that "[t]he first works to be produced about Bernardine right after his death [in 1444] were biographical: by the year 1480, there were already over a dozen written accounts of the preacher's life".[5]

Life

[edit]

Early life

[edit]Bernardino was born in 1380 to the noble Albizzeschi family in Massa Marittima, Tuscany, a town in the contado of Siena of which his father, Albertollo degli Albizzeschi, was then governor.[6] Left orphaned at six, he was raised by a pious aunt. In 1397, after a course of civil and canon law, he joined the Confraternity of Our Lady attached to the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala. Three years later, when the plague visited Siena, he ministered to the plague-stricken, and, assisted by ten companions, took upon himself for four months entire charge of this hospital.[7] He escaped the plague but was so exhausted that a fever confined him for several months.[8] In 1403 he joined the Observant branch of the Order of Friars Minor (the Franciscan Order), with strict observance of Saint Francis's Rule. Bernardino was ordained a priest in 1404 and was commissioned as a preacher the next year.[9] In about 1406 Saint Vincent Ferrer, a Dominican friar and missionary, while preaching at Alessandria in the Piedmont region of Italy, allegedly foretold that his mantle should descend upon one who was then listening to him, and said that he would return to France and Spain, leaving to Bernardino the task of evangelizing the remaining peoples of Italy.[7]

Bernardino as preacher

[edit]Preaching style

[edit]Before Bernardino, most preachers either read a prepared speech or recited a rhetorical oration. Instead of remaining cloistered and preaching only during the liturgy, Bernardino preached directly to the public. For more than 30 years, he preached all over Italy and played a great part in the religious revival of the early fifteenth century. Although he had a weak and hoarse voice, he is said to have been one of the greatest preachers of his time.[8] His style was simple, familiar, and abounding in imagery. Cynthia Polecritti, in her biography of Bernardino, notes that the texts of his sermons "are acknowledged masterpieces of colloquial Italian". He was an elegant and captivating preacher, and his use of popular imagery and creative language drew large crowds to hear his reflections. Invitations were often extended by the civil authorities rather than the ecclesiastical, as sometimes the towns would make money from the crowds that came to hear him.[10]

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Bernardino chose his themes not from the daily liturgy, but from the ordinary lives of the people of Siena. He selected biblical themes to focus on the immediate interests of his audience. This proved effective in drawing their attention.[11] Women comprised the majority of listeners, and the size of the crowd varied according to the day, time, and topic of the sermon. Polecritti notes that the subject matter of his sermons reveals much about the contemporary context of 15th-century Italy.[12]

Bernardino travelled from place to place, remaining nowhere more than a few weeks. These journeys were all made on foot. In the towns, the crowds assembled to hear him were at times so great that it became necessary to erect a pulpit on the marketplace.[13] Like Vincent Ferrer, he usually preached at dawn. His hearers, so as to ensure themselves standing room, would arrive beforehand, many coming from far-distant villages. The sermons often lasted three or four hours. He was invited to Ferrara in 1424, where he preached against the excess of luxury and immodest apparel. In Bologna, he spoke out against gambling, much to the dissatisfaction of the card manufacturers and sellers. Returning to Siena in April 1425, he preached there for 50 consecutive days.[13] His success was said to be remarkable. "Bonfires of the Vanities" were held at his sermon sites,[7] where people threw mirrors, high-heeled shoes, perfumes, locks of false hair, cards, dice, chess pieces, and other frivolities to be burned. Bernardino enjoined his listeners to abstain from blasphemy, indecent conversation, and games of chance, and to observe feast days.[13]

Bernardino was not universally popular. In L'Aquila, someone once sawed the legs of the pulpit, causing him to fall into the crowd.[citation needed]

In 1427, Bernardino was called to Siena to allay factional strife; however, he preferred preaching to being an arbitrator. When he spoke against factions and vendettas, he was uncharacteristically tactful. To Policretti, this suggests that the situation could have become violent at the smallest provocation.[14]

Both while he was alive and after his death (the first edition of his works, for the most part elaborate sermons, was printed at Lyon in 1501), the legacy of Bernardino was far from tame: of a strict, moral temper, he preached fiery sermons against many classes of people and these were riddled with denunciations. He characterized some women as "witches", and called for sodomites to be ostracized or otherwise removed from the human community. He thus was a champion of what historian Robert Moore called "the persecuting society" of late medieval Christian Europe.[15]

On women

[edit]The historian Franco Mormando notes that in the twenty large volumes of Bernardino's extant printed works, the saint has much to say about women and to women, "married, unmarried, widowed, and those enclosed in nunneries". However, at the end of his study, "Bernardino of Siena: 'Great Defender' or 'Merciless Betrayer' of Women?", Mormando concludes: "...despite his sincere moments of greater empathy with women, Bernardino proves to be very much in the mainstream of writings on women of the Trecento and Quattrocento ... Though, in his compassion for her, Bernardine would have the woman's domestic and social 'cage' be as comfortable and as humane as possible, it is there in the same traditional cage that Bernardino nonetheless wants her to remain, under the guard of father, brother, husband, or parish priest."[16]

Bernardino presented the Virgin Mary as an example for women. He advised girls never to talk to a man unless one of their parents was present.[17] In one sermon Bernardino cautions women about marrying men who care more for their dowries than for them.[18] On one occasion he asked mothers to come to church with their daughters alone so that he speak to them frankly about sexual abuse in marriage. He also spoke against the confinement of unwilling girls to convents.[19] He presented Saint Joseph as an example for men, while emphasizing Mary's obedience to her husband.

Against sodomy and homosexuality

[edit]

On sodomy (predominantly directed towards homosexual men), Bernardino keenly pointed out the reputation of the Italians beyond their own borders.[20] In the same work is a detailed analysis of Bernardino's preaching against witchcraft and Jews. He particularly decried Florentine lenience towards men having sex with men; in Verona, he approvingly reminded listeners that a man was quartered and his limbs hung from the city gates for homosexual intercourse; in Genoa, men were regularly burned if found guilty of sodomy; and in Venice a sodomite had been tied to a column along with a barrel of pitch and brushwood and set on fire. He advised the people of Siena to do the same. In 1424 he dedicated three consecutive sermons in Florence to the subject, in the course of a Lenten sermon preached in Santa Croce, he admonished his hearers:

Whenever you hear sodomy mentioned, each and every one of you spit on the ground and clean your mouth out as well. If they don't want to change their ways by any other means, maybe they will change when they're made fools of. Spit hard! Maybe the water of your spit will extinguish their fire.[21][22]

In Siena, Bernardino preached a full sermon against sodomy, including homosexuality, in 1425 and then 1427; linking it directly with fears about the depopulation as it did not lead to children and was therefore unproductive: "You don't understand that [sodomy] is the reason you have lost half your population over the last twenty-five years".[23] Over time his teachings helped mould public sentiment and dispel indifference over controlling sodomy and homosexual conduct more vigorously. Everything unpredictable or calamitous in human experience he attributed to sodomy, including floods and the plague, as well as linking the practice to local population decline.[24] After one of his sermons in Siena, four "irate sodomites" attempted to beat him with clubs.[25]

Trial in Rome

[edit]

Especially known for his devotion to the Holy Name of Jesus, which was previously associated with John of Vercelli and the Dominican order, Bernardino devised a symbol—IHS—the first three letters of the name of Jesus in Greek, in Gothic letters on a blazing sun. This was to displace the insignia of factions (for example, Guelphs and Ghibellines). The devotion spread, and the symbol began to appear in churches, homes and public buildings. Opponents thought it a dangerous innovation.[8]

In 1426, Bernardino was summoned to Rome to stand trial on charges of heresy himself for his promotion of this devotion to the Holy Name of Jesus.[26] Theologians including Paul of Venice gave their opinions. Bernardino was found innocent of heresy, and he impressed Pope Martin V sufficiently that Martin requested he preach in Rome. He thereupon preached every day for 80 days. Bernardino's zeal was such that he would prepare up to four drafts of a sermon before starting to speak. That same year, he was offered the bishopric of Siena, but declined in order to maintain his monastic and evangelical activities. In 1431, he toured Tuscany, Lombardy, Romagna, and Ancona before returning to Siena to prevent a war against Florence. Also in 1431, he declined the bishopric of Ferrara, and in 1435 he declined the bishopric of Urbino.[27]

John of Capistrano was Bernardino's friend, and James of the Marches was his disciple during these years. Cardinals urged both Pope Martin V and Pope Eugene IV to condemn Bernardino, but both almost instantly acquitted him. A trial at the Council of Florence also ended with an acquittal. The Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund sought Bernardino's counsel and intercession and Bernardino accompanied him to Rome in 1433 for his coronation.

On Contracts and Usury

[edit]Economic theory

[edit]Bernardino was the first theologian after Peter John Olivi to write an entire work systematically devoted to Scholastic economics. His greatest contribution to economics was a discussion and defence of the entrepreneur. His book, On Contracts and Usury, written during the years 1431–1433, dealt with the justification of private property, the ethics of trade, the determination of value and price, and the usury question.[27]

One of his contributions was a discussion on the functions of the business entrepreneur, whom Bernardino saw as performing the useful social function of transporting, distributing, or manufacturing goods. According to Murray Rothbard, Bernardino's insight in determining just value prefigured "...the Jevons/Austrian analysis of supply and cost over five centuries later."[28] He extended this to a theory of the "just wage", which would be determined by the demand for labour and the available supply. Wage inequality is a function of differences in skill, ability and training. Skilled workers are scarcer than unskilled so that the former will command a higher wage.[28]

Usury

[edit]Usury was one of the principal objects of Bernardino's attacks, and he did much to prepare the way for the establishment of the beneficial loan societies, known as Monti di Pietà.[7]

Bernardino followed the earlier scholastic philosophers Anselm of Canterbury and Thomas Aquinas (who quotes Aristotle) in condemning the practice of usury, which they defined as charging interest on a loan. Scholastic analysis of usury, based in part on Roman law, was both complex and, in some instances, seemingly contradictory. Interest on delayed payment was deemed valid as it was considered compensation for damages suffered by the creditor being deprived of his property.[29]

Bernardino saw usury as concentrating all the money of the city into a few hands. However, he accepted the theory of lucrum cessans, interest charged to compensate for profits foregone in lieu of capital investment.[28] A distinction was also drawn for joint ventures, in which the creditor assumed some portion of the risk.

In Milan, he was visited by a merchant who urged him to inveigh strenuously against usury, only to find that his visitor was himself a prominent usurer, whose activities were prompted by a wish to lessen competition.[13]

Anti-Semitism

[edit]Bernardino is particularly regarded today as being a "major protagonist of Christian anti-semitism".[30] In January 1427 he was in Orvieto, where he preached on the topic of usury, urging the executive to take stringent steps against all such as were addicted to this business, many of whom were Jews. Blaming the poverty of local Christians on Jewish usury, his call for Jews to be banished and isolated from their wider communities led to segregation.[31] His audiences often used his words to reinforce actions against Jews, and his preaching left a legacy of resentment on the part of Jews.[32][page needed]

Franciscan Vicar General

[edit]Soon thereafter, he withdrew again to Serracapriola to compose a further series of sermons. He resumed his missionary labours in 1436 but was forced to abandon them when he became vicar-general of the Observant branch of the Franciscans in Italy in 1438.

Bernardino had worked to grow the Observants from the outset of his religious life: although he was not in fact its founder (the origins of the Observants, or Zelanti, can be traced back to the middle of the fourteenth century). Nevertheless, Bernardino became to the Observants what Saint Bernard had been to the Cistercians, their principal support and indefatigable propagator. Instead of one hundred and thirty Friars constituting the Observance in Italy at Bernardino's reception into the order, it counted over four thousand shortly before his death. Bernardino also founded, or reformed, at least three hundred convents of Friars. He sent missionaries to different parts of Asia, and it was largely through his efforts that many ambassadors from different schismatical nations attended the Council of Florence, where he addressed the assembled Fathers in Greek.[7]

Being Vicar General inevitably cut back his opportunities to preach, but he continued to speak to the public when he could. Having in 1442 persuaded the Pope to finally accept his resignation as Vicar-General so that he might give himself more undividedly to preaching, Bernardino again resumed his missionary work. Despite the papal bull issued by Pope Eugene IV in 1443, Illius qui se pro divini, which charged Bernardino to preach the indulgence for the Crusade against the Turks, there is no record of his having done so. In 1444, notwithstanding his increasing infirmities, Bernardino, desirous that there should be no part of Italy which had not heard his voice, set out to the Kingdom of Naples.

Bernardino died that year at L'Aquila in Abruzzo and is buried in the Basilica of San Bernardino. According to tradition, his grave continued to leak blood until two factions of the city achieved reconciliation.

Canonisation and iconography

[edit]

Reports of miracles attributed to Bernardino multiplied rapidly after his death, and he was canonized in 1450, only six years after his death, by Pope Nicholas V. His feast day in the Roman Catholic Church is on 20 May, the day of his death.

Mormando observes that "Bernardino's lifetime coincided with the blossoming not only of art in general but also of full-fledged, realistic portraiture as a distinct genre. This may explain why Bernardino, it seems, has the distinction of being the first saint in Church history for whom we have an indisputably authentic portrait in art. Many of the earliest portraits were presumably based on his death mask..."[33] Bernardino also lived into the early days of the print and was the subject of portraits in his lifetime, as well as a death-mask, which were copied to make prints, so that he is one of the earliest saints to have a fairly consistent appearance in art; though many Baroque images, such as that by El Greco, are idealized compared to the realistic ones made in the decades after his death.

After his death, the Franciscans promoted an iconographical program of diffusion of images of Bernardino, which was second only to that of the founder of the order. As such, he is one of the earliest saints whose appearance was given a distinct and readily recognisable iconography. Artists of the late medieval and Renaissance periods often represented him as small and emaciated,[34] with three mitres at his feet (representing the three bishoprics which he had rejected) and holding in his hand the IHS monogram with rays emanating from it (representing his devotion to the "Holy Name of Jesus"), which was his main attribute.[35] He appears to have been a favourite in the works of Luca della Robbia, and one of the finest examples of Renaissance art includes relief carvings of the saint, which can be seen in the oratory of Perugia Cathedral.

A portrait is known to have circulated in Siena just after the death of Bernardino which, on the basis of physiognomic similarities with his death mask at L'Aquila, is believed to have been a good likeness. It is thought probable that many subsequent depictions of the saint derive from this portrait.

The most famous depictions of Bernardino are found in the cycle of frescoes of his life, which were executed towards the end of the fifteenth century by Pinturicchio in the Bufalini Chapel of Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Rome.

Veneration

[edit]Saint Bernardino is the Roman Catholic patron saint of advertising, communications, compulsive gambling, respiratory problems, as well as any problems involving the chest area. He is the patron saint of Carpi, Italy; the Philippine barangays of Kay-Anlog in Calamba, Laguna and Tuna in Cardona, Rizal; and the diocese of San Bernardino, California, USA. Siena College, a Franciscan Catholic liberal arts college in New York, USA, was named after him and placed under his spiritual patronage. The mountain pass in the Alps, Il Passo di San Bernardino, is named in honour of the saint, whose fame reached well into northern Italy and southern Switzerland.

His cult was transferred in 1453 to Poland by John of Capistrano, the same year the first Observant Friars monastery in Poland was founded in Kraków, whose namesake became Bernardino of Siena. From the monastery's name came the name of Bernardines, by which the Franciscan Observants were known in the lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[36] His cult also spread to England at an early period, and was particularly promulgated by the Observant Friars, who first established themselves in the country in Greenwich, in 1482, not forty years after his death, but who were later suppressed.[34]

See also

[edit]- Santa Maria delle Grazie (Arezzo)

- Saint symbolism

- List of Catholic saints

- Saint Bernardino of Siena, patron saint archive

- Church of San Bernardino da Siena (Amantea)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Thureau-Dangin, Paul (1906). Saint Bernadine of Siena. J.M. Dent & Company. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Guiley, Rosemary (2001). "Bernadine of Siena". The Encyclopedia of Saints. Infobase Publishing. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-4381-3026-2.

- ^ "St. Bernardine of Siena,'Apostle of Italy'", Catholic News Agency

- ^ Butler, Alban (1864). "The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs and Other Principal Saints". D. & J. Sadlier, & Company. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Mormando 1999, p. 29. See also Mormando (1999) note 90 on p. 250 for a list of critical studies of these early lives. In note 91 on the same page, Mormando says that Benvoglienti was a classmate of Bernardino's.

- ^ Mormando 1999, pp. 25–45.

- ^ a b c d e Robinson, Paschal (1907). "St. Bernardine of Siena". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Foley, O.F.M., Leonard, "St. Bernadine of Siena", Saint of the Day, Lives, Lessons, and Feast, Franciscan Media ISBN 978-0-86716-887-7

- ^ Cochrane, Eric; Julius, Kirshner (1986). Readings in Western Civilization: The Renaissance. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Mormando 1999, p. 5.

- ^ Meussig, Carolyn. "Bernardino da Siena and Obervant Preaching as a Vehicle for Religious Transformation", A Companion to Observant Reform in the Late Middle Ages and Beyond, (James Mixson and Bert Roest, eds.) Brill, 2015 ISBN 9789004297524

- ^ Horan OFM, Daniel, "The Complicated History of and the Popular Preaching of St. Bernardine of Siena", HNP Today Newsletter, Vol. 45, No. 10, May 18, 2011 Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Thureau-Dangin, Paul, Saint Bernardine of Siena, J. M. Dent & Co., London, 1906

- ^ Polecritti, Cynthia L. Preaching Peace in Renaissance Italy. Bernardino of Siena & His Audience. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8132-0960-9

- ^ R. Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Power and Deviance in Western Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987

- ^ Franco Mormando, "Bernardino of Siena: 'Great Defender' or 'Merciless Betrayer' of Women?," in Italica, vol. 75, no. 1, Spring 1998, pp. 22–40, here p. 34.

- ^ Tinagli, Paola. Women in Italian Renaissance Art, Manchester University Press, 1997 ISBN 9780719040542

- ^ "St. Bernardino of Siena: Two Sermons on Wives and Widows", Life in the Middle Ages, (C. G. Coulton, ed.), (New York: Macmillan, c. 1910), Vol. 1, 216–229

- ^ Herlihy, David. Women, Family and Society in Medieval Europe, Berghahn Books, 1995 ISBN 9781571810243

- ^ Mormando 1999, pp. 109–163.

- ^ Louis Crompton (2003). Homosexuality and Civilization. Harvard University Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-674-03006-0. OCLC 1016977065.

- ^ Mormando 1999, p. 150.

- ^ William G. Naphy (2004). Born to be Gay: A History of Homosexuality. Tempus. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-7524-2917-5. OCLC 249661077.

- ^ Michael Rocke (5 March 1998). Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence. Oxford University Press. pp. 36–44. ISBN 978-0-19-535268-9. OCLC 1038683396.

- ^ Mormando 1999, p. 6.

- ^ Mormando 1999, p. 235–237.

- ^ a b "St. Bernardino of Siena", Religion & Liberty, Vol.6, Number 2

- ^ a b c Rothbard, Murray N. (2009). "The Worldly Ascetic". Economic Thought Before Adam Smith: An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought. Vol. 1. Ludwig von Mises Institute. ISBN 9780945466482.

- ^ De Roover, Raymond (1967). San Bernardino of Siena and Sant Antonino of Florence (Report). Boston, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.366.8099.

- ^ Mormando 1999, Ch. 4.

- ^ Debby, Nirit Ben-Aryeh. "Jews and Judaism in the Rhetoric of Popular Preachers: The Florentine Sermons of Giovanni Dominici (1356–1419) and Bernardino Da Siena (1380–1444)." Jewish History 14.2 (2000): 175–200

- ^ Mormando 1999.

- ^ Mormando 1999, p. 255, note 136. On the same note, Mormando points out that in Peter Burke's "Top 10" list of the most popular saints depicted in Renaissance art, Bernardino ranks number 9.

- ^ a b Farmer, David Hugh (1997). The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (4. ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 9780192800589.

- ^ Emily Michelson, "Bernardino of Siena Visualizes the Name of God," in: Speculum Sermonis: Interdisciplinary Reflections on the Medieval Sermon, ed. Georgiana Donavin, Cary J. Nederman, and Richard Utz (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), pp. 157–79.

- ^ Rusecki, Innocenty Marek (2003). "Z dziejów ojców bernardynów w Polsce 1453-2003". Łódzkie Studia Teologiczne. 11–12: 192.

References

[edit] This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Bernardine of Siena". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Bernardine of Siena". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Polecritti, Cynthia, Preaching Peace in Renaissance Italy: San Bernardino of Siena and His Audience, (UC Berkeley, 1988)

- Mormando, Franco (May 1999). The Preacher's Demons: Bernardino of Siena and the Social Underworld of Early Renaissance Italy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-53854-9.