Honduras

Republic of Honduras República de Honduras (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Libre, Soberana e Independiente "Free, Sovereign and Independent" | |

| Anthem: Himno Nacional de Honduras "National Anthem of Honduras" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Tegucigalpa 14°6′N 87°13′W / 14.100°N 87.217°W |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Ethnic groups (2016)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Xiomara Castro | |

| Salvador Nasralla Doris Gutiérrez Renato Florentino | |

| Luis Redondo | |

| Legislature | National Congress |

| Independence | |

• Declaredb from Spain | 15 September 1821 |

• Declared from the First Mexican Empire | 1 July 1823 |

• Declared, as Honduras, from the Federal Republic of Central America | 5 November 1838 |

| Area | |

• Total | 112,492 km2 (43,433 sq mi) (101st) |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 9,571,352[2] (95th) |

• Density | 85/km2 (220.1/sq mi) (128th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | high inequality |

| HDI (2021) | medium (137th) |

| Currency | Lempira (HNL) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +504 |

| ISO 3166 code | HN |

| Internet TLD | .hn |

| |

Population estimates explicitly take into account the effects of excess mortality due to AIDS; this can result in lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality and death rates, lower population and growth rates, and changes in the distribution of population by age and sex than would otherwise be expected, as of July 2007. | |

Honduras,[a] officially the Republic of Honduras,[b] is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, and to the north by the Gulf of Honduras, a large inlet of the Caribbean Sea. Its capital and largest city is Tegucigalpa.

Honduras was home to several important Mesoamerican cultures, most notably the Maya, before Spanish colonization in the sixteenth century. The Spanish introduced Catholicism and the now predominant Spanish language, along with numerous customs that have blended with the indigenous culture. Honduras became independent in 1821 and has since been a republic, although it has consistently endured much social strife and political instability, and remains one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere. In 1960, the northern part of what was the Mosquito Coast was transferred from Nicaragua to Honduras by the International Court of Justice.[7]

The nation's economy is primarily agricultural, making it especially vulnerable to natural disasters such as Hurricane Mitch in 1998.[8] The lower class is primarily agriculturally based while wealth is concentrated in the country's urban centers.[9] Honduras has a Human Development Index of 0.625, classifying it as a nation with medium development.[10] When adjusted for income inequality, its Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index is 0.443.[10]

Honduran society is predominantly Mestizo; however, there are also significant Indigenous, black, and white communities in Honduras.[11] The nation had a relatively high political stability until a 2009 military coup and controversy arising from claims of electoral fraud in the 2017 presidential election.[12]

Honduras spans about 112,492 km2 (43,433 sq mi) and has a population exceeding 10 million.[13][14] Its northern portions are part of the western Caribbean zone, as reflected in the area's demographics and culture. Honduras is known for its rich natural resources, including minerals, coffee, tropical fruit, and sugar cane, as well as for its growing textiles industry, which serves the international market.

Etymology

The literal meaning of the term "Honduras" is "depths" in Spanish. The name could refer either to the bay of Trujillo as an anchorage, fondura in the Leonese dialect of Spain, or to Columbus's alleged quote that "Gracias a Dios que hemos salido de esas honduras" ("Thank God we have departed from those depths").[15][16][17]

It was not until the end of the 16th century that Honduras was used for the whole province. Prior to 1580, Honduras referred to only the eastern part of the province, and Higueras referred to the western part.[17] Another early name is Guaymuras, revived as the name for the political dialogue in 2009 that took place in Honduras as opposed to Costa Rica.[18]

Hondurans are often referred to as either the masculine Catracho or the feminine Catracha in Spanish.

History

Pre-colonial period

In the pre-Columbian era, modern Honduras was split between two pan-cultural regions: Mesoamerica in the west and the Isthmo-Colombian area in the east. Each complex had a "core area" within Honduras (the Sula Valley for Mesoamerica, and La Mosquitia for the Isthmo-Colombian area), and the intervening area was one of gradual transition. However, these concepts had no meaning in the Pre-Columbian era itself and represent extremely diverse areas. The Lenca people of the interior highlands are also generally considered to be culturally Mesoamerican, though the extent of linkage with other areas varied over time (for example, expanding during the zenith of the Toltec Empire).

In the extreme west, Maya civilization flourished for hundreds of years. The dominant, best known, and best studied state within Honduras's borders was in Copán, which was located in a mainly non-Maya area, or on the frontier between Maya and non-Maya areas. Copán declined with other Lowland centres during the conflagrations of the Terminal Classic in the 9th century. The Maya of this civilization survive in western Honduras as the Ch'orti', isolated from their Choltian linguistic peers to the west.[19]

However, Copán represents only a fraction of Honduran pre-Columbian history. Remnants of other civilizations are found throughout the country. Archaeologists have studied sites such as Naco and La Sierra in the Naco Valley, Los Naranjos on Lake Yojoa, Yarumela in the Comayagua Valley,[20] La Ceiba and Salitron Viejo[21] (both now under the Cajón Dam reservoir), Selin Farm and Cuyamel in the Aguan valley, Cerro Palenque, Travesia, Curruste, Ticamaya, Despoloncal, and Playa de los Muertos in the lower Ulúa River valley, and many others.

In 2012, LiDAR scanning revealed that several previously unknown high density settlements existed in La Mosquitia, corresponding to the legend of "La Ciudad Blanca". Excavation and study has since improved knowledge of the region's history. It is estimated that these settlements reached their zenith from 500 to 1000 AD.

Spanish conquest (1524–1539)

On his fourth and the final voyage to the New World in 1502, Christopher Columbus landed near the modern town of Trujillo, near Guaimoreto Lagoon, becoming the first European to visit the Bay Islands on the coast of Honduras.[22] On 30 July 1502, Columbus sent his brother Bartholomew to explore the islands and Bartholomew encountered a Mayan trading vessel from Yucatán, carrying well-dressed Maya and a rich cargo.[23][24] Bartholomew's men stole the cargo they wanted and kidnapped the ship's elderly captain to serve as an interpreter[24] in the first recorded encounter between the Spanish and the Maya.[25]

In March 1524, Gil González Dávila became the first Spaniard to enter Honduras as a conquistador.[26][27] followed by Hernán Cortés, who had brought forces down from Mexico. Much of the conquest took place in the following two decades, first by groups loyal to Cristóbal de Olid, and then by those loyal to Francisco de Montejo but most particularly by those following Alvarado.[who?] In addition to Spanish resources, the conquerors relied heavily on armed forces from Mexico—Tlaxcalans and Mexica armies of thousands who remained garrisoned in the region.

Resistance to conquest was led in particular by Lempira. Many regions in the north of Honduras never fell to the Spanish, notably the Miskito Kingdom. After the Spanish conquest, Honduras became part of Spain's vast empire in the New World within the Kingdom of Guatemala. Trujillo and Gracias were the first city-capitals. The Spanish ruled the region for approximately three centuries.

Spanish Honduras (1524–1821)

Honduras was organized as a province of the Kingdom of Guatemala and the capital was fixed, first at Trujillo on the Atlantic coast, and later at Comayagua, and finally at Tegucigalpa in the central part of the country.

Silver mining was a key factor in the Spanish conquest and settlement of Honduras.[28] Initially the mines were worked by local people through the encomienda system, but as disease and resistance made this option less available, slaves from other parts of Central America were brought in. When local slave trading stopped at the end of the sixteenth century, African slaves, mostly from Angola, were imported.[29] After about 1650, very few slaves or other outside workers arrived in Honduras.

Although the Spanish conquered the southern or Pacific portion of Honduras fairly quickly, they were less successful on the northern, or Atlantic side. They managed to found a few towns along the coast, at Puerto Caballos and Trujillo in particular, but failed to conquer the eastern portion of the region and many pockets of independent indigenous people as well. The Miskito Kingdom in the northeast was particularly effective at resisting conquest. The Miskito Kingdom found support from northern European privateers, pirates and especially the British formerly English colony of Jamaica, which placed much of the area under its protection after 1740.

Independence (1821)

Honduras gained independence from Spain in 1821 and was a part of the First Mexican Empire until 1823, when it became part of the United Provinces of Central America. It has been an independent republic and has held regular elections since 1838. In the 1840s and 1850s Honduras participated in several failed attempts at Central American unity, such as the Confederation of Central America (1842–1845), the covenant of Guatemala (1842), the Diet of Sonsonate (1846), the Diet of Nacaome (1847) and National Representation in Central America (1849–1852). Although Honduras eventually adopted the name Republic of Honduras, the unionist ideal never waned, and Honduras was one of the Central American countries that pushed the hardest for a policy of regional unity.

Policies favoring international trade and investment began in the 1870s. Soon, foreign interests became involved, first in shipping from the north coast, especially tropical fruit and most notably bananas, and then in building railroads. In 1888, a projected railroad line from the Caribbean coast to the capital, Tegucigalpa, ran out of money when it reached San Pedro Sula. As a result, San Pedro grew into the nation's primary industrial center and second-largest city. Comayagua was the capital of Honduras until 1880, when the capital moved to Tegucigalpa.

Since independence, nearly 300 small internal rebellions and civil wars have occurred in the country, including some changes of régime.[30][31]

20th century and the role of American companies

In the late nineteenth century, Honduras granted land and substantial exemptions to several US-based fruit and infrastructure companies in return for developing the country's northern regions. Thousands of workers came to the north coast as a result to work in banana plantations and other businesses that grew up around the export industry. Banana-exporting companies, dominated until 1930 by the Cuyamel Fruit Company, as well as the United Fruit Company, and Standard Fruit Company, built an enclave economy in northern Honduras, controlling infrastructure and creating self-sufficient, tax-exempt sectors that contributed relatively little to economic growth. American troops landed in Honduras in 1903, 1907, 1911, 1912, 1919, 1924 and 1925.[32]

In 1904, the writer O. Henry coined the term "banana republic" to describe Honduras,[33] publishing a book called Cabbages and Kings, about a fictional country, Anchuria, inspired by his experiences in Honduras, where he had lived for six months.[34] In The Admiral, O. Henry refers to the nation as a "small maritime banana republic"; naturally, the fruit was the entire basis of its economy.[35][36] According to a literary analyst writing for The Economist, "his phrase neatly conjures up the image of a tropical, agrarian country. But its real meaning is sharper: it refers to the fruit companies from the United States that came to exert extraordinary influence over the politics of Honduras and its neighbors."[37][38] In addition to drawing Central American workers north, the fruit companies encouraged immigration of workers from the English-speaking Caribbean, notably Jamaica and Belize, which introduced an African-descended, English-speaking and largely Protestant population into the country, although many of these workers left following changes to immigration law in 1939.[39] Honduras joined the Allied Nations after Pearl Harbor, on 8 December 1941, and signed the Declaration by United Nations on 1 January 1942, along with twenty-five other governments.

Constitutional crises in the 1940s led to reforms in the 1950s. One reform gave workers permission to organize, and a 1954 general strike paralyzed the northern part of the country for more than two months, but led to reforms. In 1963 a military coup unseated democratically elected President Ramón Villeda Morales. In 1960, the northern part of what was the Mosquito Coast was transferred from Nicaragua to Honduras by the International Court of Justice.[7]

War and upheaval (1969–1999)

In 1969, Honduras and El Salvador fought what became known as the Football War.[40] Border tensions led to acrimony between the two countries after Oswaldo López Arellano, the president of Honduras, blamed the deteriorating Honduran economy on immigrants from El Salvador. The relationship reached a low when El Salvador met Honduras for a three-round football elimination match preliminary to the World Cup.[41]

Tensions escalated and on 14 July 1969, the Salvadoran army invaded Honduras.[40] The Organization of American States (OAS) negotiated a cease-fire which took effect on 20 July and brought about a withdrawal of Salvadoran troops in early August.[41] Contributing factors to the conflict were a boundary dispute and the presence of thousands of Salvadorans living in Honduras illegally. After the week-long war, as many as 130,000 Salvadoran immigrants were expelled.[9]

Hurricane Fifi caused severe damage when it skimmed the northern coast of Honduras on 18 and 19 September 1974. Melgar Castro (1975–78) and Paz Garcia (1978–82) largely built the current physical infrastructure and telecommunications system of Honduras.[42]

In 1979, the country returned to civilian rule. A constituent assembly was popularly elected in April 1980 to write a new constitution, and general elections were held in November 1981. The constitution was approved in 1982 and the PLH government of Roberto Suazo won the election with a promise to carry out an ambitious program of economic and social development to tackle the recession in which Honduras found itself. He launched ambitious social and economic development projects sponsored by American development aid. Honduras became host to the largest Peace Corps mission in the world, and nongovernmental and international voluntary agencies proliferated. The Peace Corps withdrew its volunteers in 2012, citing safety concerns.[43]

During the early 1980s, the United States established a continuing military presence in Honduras to support El Salvador, the Contra guerrillas fighting the Nicaraguan government, and also develop an airstrip and modern port in Honduras. Though spared the bloody civil wars wracking its neighbors, the Honduran army quietly waged campaigns against Marxist–Leninist militias such as the Cinchoneros Popular Liberation Movement, notorious for kidnappings and bombings,[44] and against many non-militants as well. The operation included a campaign of extrajudicial killings by government units, most notably the CIA-trained Battalion 316.[45] Honduras was found internationally liable for a series of enforced disappearances during this time period, culminating in Velásquez-Rodríguez v. Honduras.[46]

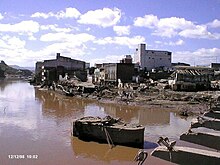

In 1998, Hurricane Mitch caused massive and widespread destruction. Honduran President Carlos Roberto Flores said that fifty years of progress in the country had been reversed. Mitch destroyed about 70% of the country's crops and an estimated 70–80% of the transportation infrastructure, including nearly all bridges and secondary roads. Across Honduras 33,000 houses were destroyed, and an additional 50,000 damaged. Some 5,000 people killed, and 12,000 more injured. Total losses were estimated at US$3 billion.[47]

21st century

In 2007, President of Honduras Manuel Zelaya and President of the United States George W. Bush began talks on US assistance to Honduras to tackle the latter's growing drug cartels in Mosquito, Eastern Honduras using US special forces. This marked the beginning of a new foothold for the US military's continued presence in Central America.[48]

Under Zelaya, Honduras joined ALBA in 2008, but withdrew in 2010 after the 2009 Honduran coup d'état.[49] In 2009, a constitutional crisis resulted when power was transferred in a coup from the president to the head of Congress. The OAS suspended Honduras because it did not regard its government as legitimate.[50][51]

Countries around the world, the OAS, and the United Nations[52] formally and unanimously condemned the action as a coup d'état, refusing to recognize the de facto government, even though the lawyers consulted by the Library of Congress submitted to the United States Congress an opinion that declared the coup legal.[52][53][54] The Honduran Supreme Court also ruled that the proceedings had been legal. The government that followed the de facto government established a truth and reconciliation commission, Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación, which after more than a year of research and debate concluded that the ousting had been a coup d'état, and illegal in the commission's opinion.[55][56][57]

On 28 November 2021, the former first lady Xiomara Castro, leftist presidential candidate of opposition Liberty and Refoundation Party, won 53% of the votes in the presidential election to become the first female president of Honduras, bringing an end to the 12-year reign of the right-wing National Party.[58] She was sworn in on 27 January 2022. Her husband, Manuel Zelaya, held the same office from 2006 until 2009.[59]

In April 2022, former president of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernández, who served two terms between 2014 and January 2022, was extradited to the United States to face charges of drug trafficking and money laundering. Hernandez denied the accusations.[60]

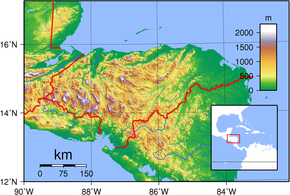

Geography

The north coast of Honduras borders the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean lies south through the Gulf of Fonseca. Honduras consists mainly of mountains, with narrow plains along the coasts. A large undeveloped lowland jungle, La Mosquitia lies in the northeast, and the heavily populated lowland Sula valley in the northwest. In La Mosquitia lies the UNESCO world-heritage site Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve, with the Coco River which divides Honduras from Nicaragua.

The Islas de la Bahía and the Swan Islands are off the north coast. Misteriosa Bank and Rosario Bank, 130 to 150 kilometres (81 to 93 miles) north of the Swan Islands, fall within the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of Honduras.

Natural resources include timber, gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, iron ore, antimony, coal, fish, shrimp, and hydropower.

Climate

The climate varies from tropical in the lowlands to temperate in the mountains. The Pacific coast is generally drier than the Caribbean.

Biodiversity

The region is considered a biodiversity hotspot because of the many plant and animal species found there. Like other countries in the region, it contains vast biological resources. Honduras hosts more than 6,000 species of vascular plants, of which 630 (described so far) are orchids; around 250 reptiles and amphibians, more than 700 bird species, and 110 mammalian species, of which half are bats.[61]

In the northeastern region of La Mosquitia lies the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve, a lowland rainforest which is home to a great diversity of life. The reserve was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites List in 1982.

Honduras has rain forests, cloud forests (which can rise up to nearly 3,000 metres or 9,800 feet above sea level), mangroves, savannas and mountain ranges with pine and oak trees, and the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System. In the Bay Islands there are bottlenose dolphins, manta rays, parrot fish, schools of blue tang and whale shark.

Deforestation resulting from logging is rampant in Olancho Department. The clearing of land for agriculture is prevalent in the largely undeveloped La Mosquitia region, causing land degradation and soil erosion. Honduras had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.48/10, ranking it 126th globally out of 172 countries.[62]

Lake Yojoa, which is Honduras's largest source of fresh water, is polluted by heavy metals produced from mining activities.[63] Some rivers and streams are also polluted by mining.[64]

Government and politics

Honduras is governed within a framework of a presidential representative democratic republic. The President of Honduras is both head of state and head of government. Executive power is exercised by the Honduran government. Legislative power is vested in the National Congress of Honduras. The judiciary is independent of both the executive branch and the legislature.

The National Congress of Honduras (Congreso Nacional) has 128 members (diputados), elected for a four-year term by proportional representation. Congressional seats are assigned the parties' candidates on a departmental basis in proportion to the number of votes each party receives.[1]

Political culture

In 1963, a military coup removed the democratically elected president, Ramón Villeda Morales. A string of authoritarian military governments held power uninterrupted until 1981, when Roberto Suazo Córdova was elected president.

The party system was dominated by the conservative National Party of Honduras (Partido Nacional de Honduras: PNH) and the liberal Liberal Party of Honduras (Partido Liberal de Honduras: PLH) until the 2009 Honduran coup d'état removed Manuel Zelaya from office and put Roberto Micheletti in his place.

In late 2012, 1540 persons were interviewed by ERIC in collaboration with the Jesuit university, as reported by Associated Press. This survey found that 60.3% believed the police were involved in crime, 44.9% had "no confidence" in the Supreme Court, and 72% thought there was electoral fraud in the primary elections of November 2012. Also, 56% expected the presidential, legislative and municipal elections of 2013 to be fraudulent.[65]

Then-president Juan Orlando Hernández took office on 27 January 2014. After managing to stand for a second term,[66] a very close election in 2017 left uncertainty as to whether then-President Hernandez or his main challenger, television personality Salvador Nasralla, had prevailed.[67] The disputed election caused protests and violence. In December 2017, Hernández was declared the winner of the election after a partial recount.[68] In January 2018, Hernández was sworn in for a second presidential term.[69] He was succeeded by Xiomara Castro, the leader of the left-wing Libre Party, and wife of Manuel Zelaya, on 27 January 2022, becoming the first woman to serve as president.[70]

Foreign relations

Honduras and Nicaragua had tense relations throughout 2000 and early 2001 due to a boundary dispute off the Atlantic coast. Nicaragua imposed a 35% tariff against Honduran goods due to the dispute.[71]

In June 2009 a coup d'état ousted President Manuel Zelaya; he was taken in a military aircraft to Costa Rica. The General Assembly of the United Nations voted to denounce the coup and called for the restoration of Zelaya. Several Latin American nations, including Mexico, temporarily severed diplomatic relations with Honduras. In July 2010, full diplomatic relations were once again re-established with Mexico.[72] The United States sent out mixed messages after the coup; U.S. President Obama called the ouster a coup and expressed support for Zelaya's return to power. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, advised by John Negroponte, the former Reagan-era Ambassador to Honduras implicated in the Iran–Contra affair, refrained from expressing support.[73] She has since explained that the US would have had to cut aid if it called Zelaya's ouster a military coup, although the US has a record of ignoring these events when it chooses.[74] Zelaya had expressed an interest in Hugo Chávez' Bolivarian Alliance for Peoples of our America (ALBA), and had actually joined in 2008. After the 2009 coup, Honduras withdrew its membership.[49]

This interest in regional agreements may have increased the alarm of establishment politicians. When Zelaya began calling for a "fourth ballot box" to determine whether Hondurans wished to convoke a special constitutional congress, this sounded a lot to some like the constitutional amendments that had extended the terms of both Hugo Chávez and Evo Morales. "Chávez has served as a role model for like-minded leaders intent on cementing their power. These presidents are barely in office when they typically convene a constitutional convention to guarantee their reelection," said a 2009 Spiegel International analysis,[75] which noted that one reason to join ALBA was discounted Venezuelan oil. In addition to Chávez and Morales, Carlos Menem of Argentina, Fernando Henrique Cardoso of Brazil and Columbian President Álvaro Uribe had all taken this step, and Washington and the EU were both accusing the Sandinista National Liberation Front government in Nicaragua of tampering with election results.[75] Politicians of all stripes expressed opposition to Zelaya's referendum proposal, and the Attorney-General accused him of violating the constitution. The Honduran Supreme Court agreed, saying that the constitution had put the Supreme Electoral Tribunal in charge of elections and referenda, not the National Statistics Institute, which Zelaya had proposed to have run the count.[76] Whether or not Zelaya's removal from power had constitutional elements, the Honduran constitution explicitly protects all Hondurans from forced expulsion from Honduras.

The United States maintains a small military presence at one Honduran base. The two countries conduct joint peacekeeping, counter-narcotics, humanitarian, disaster relief, humanitarian, medical and civic action exercises. U.S. troops conduct and provide logistics support for a variety of bilateral and multilateral exercises. The United States is Honduras's chief trading partner.[42]

Honduras has been a member of The Forum of Small States (FOSS) since the group's founding in 1992.[77]

Military

Honduras has a military with the Honduran Army, Honduran Navy and Honduran Air Force.

In 2017, Honduras signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[78]

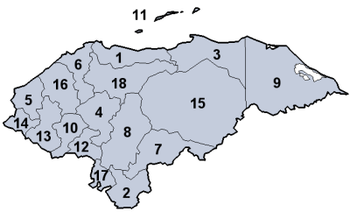

Administrative divisions

Honduras is divided into 18 departments. The capital city is Tegucigalpa in the Central District within the department of Francisco Morazán.

- Atlántida

- Choluteca

- Colón

- Comayagua

- Copán

- Cortés

- El Paraíso

- Francisco Morazán

- Gracias a Dios

- Intibucá

- Bay Islands

- La Paz

- Lempira

- Ocotepeque

- Olancho

- Santa Bárbara

- Valle

- Yoro

A new administrative division called ZEDE (Zonas de empleo y desarrollo económico) was created in 2013. ZEDEs have a high level of autonomy with their own political system at a judicial, economic and administrative level, and are based on free market capitalism.

Economy

The economy of Honduras is based mostly on agriculture, which accounts for 14% of its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2013. The country's leading export is coffee (US$340 million), which accounted for 22% of the total Honduran export revenues. Bananas, formerly the country's second-largest export until being virtually wiped out by 1998's Hurricane Mitch, recovered in 2000 to 57% of pre-Mitch levels. Cultivated shrimp is another important export sector. Since the late 1970s, towns in the north began industrial production through maquiladoras, especially in San Pedro Sula and Puerto Cortés.[79]

Honduras has extensive forests, marine, and mineral resources, although widespread slash and burn agricultural methods continue to destroy Honduran forests. The Honduran economy grew 4.8% in 2000, recovering from the Mitch-induced recession (−1.9%) of 1999. The Honduran maquiladora sector, the third-largest in the world, continued its strong performance in 2000, providing employment to over 120,000 and generating more than $528 million in foreign exchange for the country. Inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, was 10.1% in 2000, down slightly from the 10.9% recorded in 1999. The country's international reserve position continued to be strong in 2000, at slightly over US$1 billion. Remittances from Hondurans living abroad (mostly in the United States) rose 28% to $410 million in 2000. The Lempira (currency) was devaluing for many years, but stabilized at L19 to the United States dollar in 2005. The Honduran people are among the poorest in Latin America; gross national income per capita (2007) is US$1,649; the average for Central America is $6,736.[80] Honduras is the fourth poorest country in the Western Hemisphere; only Haiti, Nicaragua, and Guyana are poorer. Using alternative statistical measurements in addition to the gross domestic product can provide greater context for the nation's poverty.

The country signed an Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF) – later converted to a Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) with the International Monetary Fund in March 1999. Honduras (as of the about year 2000) continues to maintain stable macroeconomic policies. It has not been swift in implementing structural changes, such as privatization of the publicly owned telephone and energy distribution companies—changes which are desired by the IMF and other international lenders. Honduras received significant debt relief in the aftermath of Hurricane Mitch, including the suspension of bilateral debt service payments and bilateral debt reduction by the Paris Club—including the United States – worth over $400 million. In July 2000, Honduras reached its decision point under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC), qualifying the country for interim multilateral debt relief.

Land appears to be plentiful and readily exploitable, but the presence of apparently extensive land is misleading because the nation's rugged, mountainous terrain restricts large-scale agricultural production to narrow strips on the coasts and to a few fertile valleys. Honduras's manufacturing sector has not yet developed beyond simple textile and agricultural processing industries and assembly operations. The small domestic market and competition from more industrially advanced countries in the region have inhibited more complex industrialization.

In 2022, according to the National Institute of Statistics of Honduras (INE), 73% of the country's population is poor and 53% lives in extreme poverty.[81] The country is one of the most unequal in Latin America.[82]

Poverty

The World Bank categorizes Honduras as a low middle-income nation.[83] The nation's per capita income sits at around 600 US dollars making it one of the lowest in North America.[84]

In 2016, more than 66% of the population was living below the poverty line.[83]

Economic growth in the last few years has averaged 7% a year, one of the highest rates in Latin America (2010).[83] Despite this, Honduras has seen the least development amongst all Central American countries.[85] Honduras is ranked 130 of 188 countries with a Human Development Index of .625 that classifies the nation as having medium development (2015).[10] The three factors that go into Honduras's HDI (an extended and healthy life, accessibility of knowledge and standard of living) have all improved since 1990 but still remain relatively low with life expectancy at birth being 73.3, expected years of schooling being 11.2 (mean of 6.2 years) and GNI per capita being $4,466 (2015).[10] The HDI for Latin America and the Caribbean overall is 0.751 with life expectancy at birth being 68.6, expected years of schooling being 11.5 (mean of 6.6) and GNI per capita being $6,281 (2015).[10]

The 2009 Honduran coup d'état led to a variety of economic trends in the nation.[86] Overall growth has slowed, averaging 5.7 percent from 2006 to 2008 but slowing to 3.5 percent annually between 2010 and 2013.[86] Following the coup trends of decreasing poverty and extreme poverty were reversed. The nation saw a poverty increase of 13.2 percent and in extreme poverty of 26.3 percent in just 3 years.[86] Furthermore, unemployment grew between 2008 and 2012 from 6.8 percent to 14.1 percent.[86]

Because much of the Honduran economy is based on small scale agriculture of only a few exports, natural disasters have a particularly devastating impact. Natural disasters, such as 1998 Hurricane Mitch, have contributed to this inequality as they particularly affect poor rural areas.[87] Additionally, they are a large contributor to food insecurity in the country as farmers are left unable to provide for their families.[87] A study done by Honduras NGO, World Neighbors, determined the terms "increased workload, decreased basic grains, expensive food, and fear" were most associated with Hurricane Mitch.[88]

The rural and urban poor were hit hardest by Hurricane Mitch.[87] Those in southern and western regions specifically were considered most vulnerable as they both were subject to environmental destruction and home to many subsistence farmers.[87] Due to disasters such as Hurricane Mitch, the agricultural economic sector has declined a third in the past twenty years.[87] This is mostly due to a decline in exports, such as bananas and coffee, that were affected by factors such as natural disasters.[87] Indigenous communities along the Patuca River were hit extremely hard as well.[8] The mid-Pataca region was almost completely destroyed.[8] Over 80% of rice harvest and all of banana, plantain, and manioc harvests were lost.[8] Relief and reconstruction efforts following the storm were partial and incomplete, reinforcing existing levels of poverty rather than reversing those levels, especially for indigenous communities.[8] The period between the end of food donations and the following harvest led to extreme hunger, causing deaths amongst the Tawahka population.[8] Those that were considered the most "land-rich" lost 36% of their total land on average.[8] Those that were the most "land-poor", lost less total land but a greater share of their overall total.[8] This meant that those hit hardest were single women as they constitute the majority of this population.[8]

Poverty reduction strategies

Since the 1970s when Honduras was designated a "food priority country" by the UN, organizations such as The World Food Program (WFP) have worked to decrease malnutrition and food insecurity.[89] A large majority of Honduran farmers live in extreme poverty, or below 180 US dollars per capita.[90] Currently one fourth of children are affected by chronic malnutrition.[89] WFP is currently working with the Honduran government on a School Feeding Program which provides meals for 21,000 Honduran schools, reaching 1.4 million school children.[89] WFP also participates in disaster relief through reparations and emergency response in order to aid in quick recovery that tackles the effects of natural disasters on agricultural production.[89]

Honduras's Poverty Reduction Strategy was implemented in 1999 and aimed to cut extreme poverty in half by 2015.[91] While spending on poverty-reduction aid increased there was only a 2.5% increase in GDP between 1999 and 2002.[92] This improvement left Honduras still below that of countries that lacked aid through Poverty Reduction Strategy behind those without it.[92] The World Bank believes that this inefficiency stems from a lack of focus on infrastructure and rural development.[92] Extreme poverty saw a low of 36.2 percent only two years after the implementation of the strategy but then increased to 66.5 percent by 2012.[86]

Poverty Reduction Strategies were also intended to affect social policy through increased investment in education and health sectors.[93] This was expected to lift poor communities out of poverty while also increasing the workforce as a means of stimulating the Honduran economy.[93] Conditional cash transfers were used to do this by the Family Assistance Program.[93] This program was restructured in 1998 in an attempt to increase effectiveness of cash transfers for health and education specifically for those in extreme poverty.[93] Overall spending within Poverty Reduction Strategies have been focused on education and health sectors increasing social spending from 44% of Honduras's GDP in 2000 to 51% in 2004.[93]

Critics of aid from International Finance Institutions believe that the World Bank's Poverty Reduction Strategy result in little substantive change to Honduran policy.[93] Poverty Reduction Strategies also excluded clear priorities, specific intervention strategy, strong commitment to the strategy and more effective macro-level economic reforms according to Jose Cuesta of Cambridge University.[92] Due to this he believes that the strategy did not provide a pathway for economic development that could lift Honduras out of poverty resulting in neither lasting economic growth of poverty reduction.[92]

Prior to its 2009 coup Honduras widely expanded social spending and an extreme increase in minimum wage.[86] Efforts to decrease inequality were swiftly reversed following the coup.[86] When Zelaya was removed from office social spending as a percent of GDP decreased from 13.3 percent in 2009 to 10.9 recent in 2012.[86] This decrease in social spending exacerbated the effects of the recession, which the nation was previously relatively well equipped to deal with.[86]

Economic inequality

Levels of income inequality in Honduras are higher than in any other Latin American country.[86] Unlike other Latin American countries, inequality steadily increased in Honduras between 1991 and 2005.[91] Between 2006 and 2010 inequality saw a decrease but increased again in 2010.[86]

When Honduras's Human Development Index is adjusted for inequality (known as the IHDI) Honduras's development index is reduced to .443.[10] The levels of inequality in each aspect of development can also be assessed.[10] In 2015 inequality of life expectancy at birth was 19.6%, inequality in education was 24.4% and inequality in income was 41.5% [10] The overall loss in human development due to inequality was 29.2.[10]

The IHDI for Latin America and the Caribbean overall is 0.575 with an overall loss of 23.4%.[10] In 2015 for the entire region, inequality of life expectancy at birth was 22.9%, inequality in education was 14.0% and inequality in income was 34.9%.[10] While Honduras has a higher life expectancy than other countries in the region (before and after inequality adjustments), its quality of education and economic standard of living are lower.[10] Income inequality and education inequality have a large impact on the overall development of the nation.[10]

Inequality also exists between rural and urban areas as it relates to the distribution of resources.[94] Poverty is concentrated in southern, eastern, and western regions where rural and indigenous peoples live. North and central Honduras are home to the country's industries and infrastructure, resulting in low levels of poverty.[84] Poverty is concentrated in rural Honduras, a pattern that is reflected throughout Latin America.[11] The effects of poverty on rural communities are vast. Poor communities typically live in adobe homes, lack material resources, have limited access to medical resources, and live off of basics such as rice, maize and beans.[95]

The lower class predominantly consists of rural subsistence farmers and landless peasants.[96] Since 1965 there has been an increase in the number of landless peasants in Honduras which has led to a growing class of urban poor individuals.[96] These individuals often migrate to urban centers in search of work in the service sector, manufacturing, or construction.[96] Demographers believe that without social and economic reform, rural to urban migration will increase, resulting in the expansion of urban centers.[96] Within the lower class, underemployment is a major issue.[96] Individuals that are underemployed often only work as part-time laborers on seasonal farms meaning their annual income remains low.[96] In the 1980s peasant organizations and labor unions such as the National Federation of Honduran Peasants, The National Association of Honduran Peasants and the National Union of Peasants formed.[96]

It is not uncommon for rural individuals to voluntarily enlist in the military, however this often does not offer stable or promising career opportunities.[97] The majority of high-ranking officials in the Honduran army are recruited from elite military academies.[97] Additionally, the majority of enlistment in the military is forced.[97] Forced recruitment largely relies on an alliance between the Honduran government, military and upper class Honduran society.[97] In urban areas males are often sought out from secondary schools while in rural areas roadblocks aided the military in handpicking recruits.[97] Higher socio-economic status enables individuals to more easily evade the draft.[97]

Middle class Honduras is a small group defined by relatively low membership and income levels.[96] Movement from lower to middle class is typically facilitated by higher education.[96] Professionals, students, farmers, merchants, business employees, and civil servants are all considered a part of the Honduran middle class.[96] Opportunities for employment and the industrial and commercial sectors are slow-growing, limiting middle class membership.[96]

The Honduran upper class has much higher income levels than the rest of the Honduran population reflecting large amounts of income inequality.[96] Much of the upper class affords their success to the growth of cotton and livestock exports post-World War II.[96] The wealthy are not politically unified and differ in political and economic views.[96]

Trade

The currency is the Honduran lempira.

The government operates both the electrical grid, Empresa Nacional de Energía Eléctrica (ENEE) and the land-line telephone service, Hondutel. ENEE receives heavy subsidies to counter its chronic financial problems, but Hondutel is no longer a monopoly. The telecommunication sector was opened to private investment on 25 December 2005, as required under CAFTA. The price of petroleum is regulated, and the Congress often ratifies temporary price regulation for basic commodities.

Gold, silver, lead and zinc are mined.[99]

In 2005 Honduras signed CAFTA, a free trade agreement with the United States. In December 2005, Puerto Cortés, the primary seaport of Honduras, was included in the U.S. Container Security Initiative.[100]

In 2006 the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Energy announced the first phase of the Secure Freight Initiative (SFI), which built upon existing port security measures. SFI gave the U.S. government enhanced authority, allowing it to scan containers from overseas[clarification needed] for nuclear and radiological materials in order to improve the risk assessment of individual US-bound containers. The initial phase of Secure Freight involved deploying of nuclear detection and other devices to six foreign ports:

- Port Qasim in Pakistan;

- Puerto Cortés in Honduras;

- Southampton in the United Kingdom;

- Port of Salalah in Oman;

- Port of Singapore;

- Gamman Terminal at Port Busan, Korea.

Containers in these ports have been scanned since 2007 for radiation and other risk factors before they are allowed to depart for the United States.[101]

For economic development a 2012 memorandum of understanding with a group of international investors obtained Honduran government approval to build a zone (city) with its own laws, tax system, judiciary and police, but opponents brought a suit against it in the Supreme Court, calling it a "state within a state".[102] In 2013, Honduras's Congress ratified Decree 120, which led to the establishment of ZEDEs. The government began construction of the first zones in June 2015.[103]

Energy

About half of the electricity sector in Honduras is privately owned. The remaining generation capacity is run by ENEE (Empresa Nacional de Energía Eléctrica). Key challenges in the sector are:

- Financing investments in generation and transmission without either a financially healthy utility or concessionary funds from external donors

- Re-balancing tariffs, cutting arrears and reducing losses, including electricity theft, without social unrest

- Reconciling environmental concerns with government objectives – two large new dams and associated hydropower plants.

- Improving access to electricity in rural areas.

Transportation

Infrastructure for transportation in Honduras consists of: 699 kilometres (434 miles) of railways; 13,603 kilometres (8,453 miles) of roadways;[1] six ports;[104] and 112 airports altogether (12 Paved, 100 unpaved).[1] The Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Housing (SOPRTRAVI in Spanish acronym) is responsible for transport sector policy.

Demographics

Honduras had a population of 10,278,345 in 2021.[13][14] The proportion of the population below the age of 15 in 2010 was 36.8%, 58.9% were between 15 and 65 years old, and 4.3% were 65 years old or older.[105]

Since 1975, emigration from Honduras has accelerated as economic migrants and political refugees sought a better life elsewhere. A majority of expatriate Hondurans live in the United States. A 2012 US State Department estimate suggested that between 800,000 and one million Hondurans lived in the United States at that time, nearly 15% of the Honduran population.[42] The large uncertainty about numbers is because numerous Hondurans live in the United States without a visa. In the 2010 census in the United States, 617,392 residents identified as Hondurans, up from 217,569 in 2000.[106]

Race and ethnicity

Ethnic groups in Honduras %[107]

The ethnic breakdown of Honduran society was 90% Mestizo, 7% American Indian, 2% Black and 1% White (2017).[11] The 1927 Honduran census provides no racial data but in 1930 five classifications were created: white, Indian, Negro, yellow, and mestizo.[108] This system was used in the 1935 and 1940 census.[108] Mestizo was used to describe individuals that did not fit neatly into the categories of white, American Indian, negro or yellow or who are of mixed white-American Indian descent.[108]

John Gillin considers Honduras to be one of thirteen "Mestizo countries" (Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Cuba, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay).[109] He claims that in much of Spanish America little attention is paid to race and race mixture resulting in social status having little reliance on one's physical features.[109] However, in "Mestizo countries" such as Honduras, this is not the case.[109] Social stratification from Spain was able to develop in these countries through colonization.[109]

During colonization the majority of Honduras's indigenous population died of diseases like smallpox and measles resulting in a more homogenous indigenous population compared to other colonies.[96] Nine indigenous and African groups are recognized by the government in Honduras.[110] The majority of Amerindians in Honduras are Lenca, followed by the Miskito, Cho'rti', Tolupan, Pech and Sumo.[110] Around 50,000 Lenca individuals live in the west and western interior of Honduras while the other small native groups are located throughout the country.[96]

The majority of blacks in Honduras are ladino, meaning they are culturally Latino.[96] Non-ladino groups in Honduras include the Garifuna, Miskito, Bay Island Creoles, and Arab immigrants.[96] The Garifunas descended from freed slaves from the island of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.[96] The Bay Island Creoles are the descendants of freed African slaves from the British Empire, which administered the Bay Islands from early 17th century to 1850. The Creoles, the Garinagu, and the Miskitos are extremely racially diverse.[96] While the Garinagu and Miskitos have similar origins, Garifunas are considered black while Miskitos are considered indigenous.[96] This is largely a reflection of cultural differences, as Garinagu have retained much of their original African culture.[96] The majority of Arab Hondurans are of Palestinian and Lebanese descent.[96] They are known as "turcos" in Honduras because of migration during the rule of the Ottoman Empire.[96] They have maintained cultural distinctiveness and prospered economically.[96]

Gender

The male to female ratio of the Honduran population is 1.01. This ratio stands at 1.05 at birth, 1.04 from 15 to 24 years old, 1.02 from 25 to 54 years old, .88 from 55 to 64 years old, and .77 for those 65 years or older.[11]

The Gender Development Index (GDI) was .942 in 2015 with an HDI of .600 for females and .637 for males.[10] Life expectancy at birth for males is 70.9 and 75.9 for females.[10] Expected years of schooling in Honduras is 10.9 years for males (mean of 6.1) and 11.6 for females (mean of 6.2).[10] These measures do not reveal a large disparity between male and female development levels, however, GNI per capita is vastly different by gender.[10] Males have a GNI per capita of $6,254 while that of females is only $2,680.[10] Honduras's overall GDI is higher than that of other medium HDI nations (.871) but lower than the overall HDI for Latin America and the Caribbean (.981).[10]

The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) ranks Honduras 116th for measures including women's political power, and female access to resources.[111] The Gender Inequality Index (GII) depicts gender-based inequalities in Honduras according to reproductive health, empowerment, and economic activity.[10] Honduras has a GII of .461 and ranked 101 of 159 countries in 2015.[10] 25.8% of Honduras's parliament is female and 33.4% of adult females have a secondary education or higher while only 31.1% of adult males do.[10] Despite this, while male participation in the labor market is 84.4, female participation is 47.2%.[10] Honduras's maternal mortality ratio is 129 and the adolescent birth rate is 65.0 for women ages 15–19.[10]

Familialism and machismo carry a lot of weight within Honduran society.[112] Familialism refers to the idea of individual interests being second to that of the family, most often in relation to dating and marriage, abstinence, and parental approval and supervision of dating.[112] Aggression and proof of masculinity through physical dominance are characteristic of machismo.[112]

Honduras has historically functioned with a patriarchal system like many other Latin American countries.[113] Honduran men claim responsibility for family decisions including reproductive health decisions.[113] Recently Honduras has seen an increase in challenges to this notion as feminist movements and access to global media increases.[113] There has been an increase in educational attainment, labor force participating, urban migration, late-age marriage, and contraceptive use amongst Honduran women.[113]

Between 1971 and 2001 Honduran total fertility rate decreased from 7.4 births to 4.4 births.[113] This is largely attributable to an increase in educational attainment and workforce participation by women, as well as more widespread use of contraceptives.[113] In 1996 50% of women were using at least one type of contraceptive.[113] By 2001 62% were largely due to female sterilization, birth control in the form of a pill, injectable birth control, and IUDs.[113] A study done in 2001 of Honduran men and women reflect conceptualization of reproductive health and decision making in Honduras.[113] 28% of men and 25% of women surveyed believed men were responsible for decisions regarding family size and family planning uses.[113] 21% of men believed men were responsible for both.[113]

Sexual violence against women has proven to be a large issue in Honduras that has caused many to migrate to the U.S.[114] The prevalence of child sexual abuse was 7.8% in Honduras with the majority of reports being from children under the age of 11.[115] Women that experienced sexual abuse as children were found to be twice as likely to be in violent relationships.[115] Femicide is widespread in Honduras.[114] In 2014, 40% of unaccompanied refugee minors were female.[114] Gangs are largely responsible for sexual violence against women as they often use sexual violence.[114] Between 2005 and 2013 according to the UN Special Repporteur on Violence Against Women, violent deaths increased 263.4 percent.[114] Impunity for sexual violence and femicide crimes was 95 percent in 2014.[114] Additionally, many girls are forced into human trafficking and prostitution.[114]

Between 1995 and 1997 Honduras recognized domestic violence as both a public health issue and a punishable offense due to efforts by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).[111] PAHO's subcommittee on Women, Health and Development was used as a guide to develop programs that aid in domestic violence prevention and victim assistance programs [111] However, a study done in 2009 showed that while the policy requires health care providers to report cases of sexual violence, emergency contraception, and victim referral to legal institutions and support groups, very few other regulations exist within the realm of registry, examination and follow-up.[116] Unlike other Central American countries such as El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua, Honduras does not have detailed guidelines requiring service providers to be extensively trained and respect the rights of sexual violence victims.[116] Since the study was done the UNFPA and the Health Secretariat of Honduras have worked to develop and implement improved guidelines for handling cases of sexual violence.[116]

An educational program in Honduras known as Sistema de Aprendizaje Tutorial (SAT) has attempted to "undo gender" through focusing on gender equality in everyday interactions.[117] Honduras's SAT program is one of the largest in the world, second only to Colombia's with 6,000 students.[117] It is currently sponsored by Asociacion Bayan, a Honduran NGO, and the Honduran Ministry of Education.[117] It functions by integrating gender into curriculum topics, linking gender to the ideas of justice and equality, encouraging reflection, dialogue and debate and emphasizing the need for individual and social change.[117] This program was found to increase gender consciousness and a desire for gender equality amongst Honduran women through encouraging discourse surrounding existing gender inequality in the Honduran communities.[117]

Languages

Spanish is the official, national language, spoken by virtually all Hondurans. In addition to Spanish, a number of indigenous languages are spoken in some small communities. Other languages spoken by some include Honduran sign language and Bay Islands Creole English.[118]

The main indigenous languages are:

- Garifuna (Arawakan) (almost 100,000 speakers in Honduras including monolinguals)

- Mískito (Misumalpan) (29,000 speakers in Honduras)

- Mayangna (Misumalpan) (less than 1000 speakers in Honduras, more in Nicaragua)

- Pech/Paya, (Chibchan) (less than 1000 speakers)

- Tol (Jicaquean) (less than 500 speakers)

- Ch'orti' (Mayan) (less than 50 speakers)

The Lenca isolate lost all its fluent native speakers in the 20th century but is currently undergoing revival efforts among the members of the ethnic population of about 100,000. The largest immigrant languages are Arabic (42,000), Armenian (1,300), Turkish (900), Yue Chinese (1,000).[118]

Largest cities

| Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tegucigalpa  San Pedro Sula |

1 | Tegucigalpa | Francisco Morazán | 996,658 |  La Ceiba  Choloma | ||||

| 2 | San Pedro Sula | Cortés | 598,519 | ||||||

| 3 | La Ceiba | Atlántida | 176,212 | ||||||

| 4 | Choloma | Cortés | 163,818 | ||||||

| 5 | El Progreso | Yoro | 114,934 | ||||||

| 6 | Comayagua | Comayagua | 92,883 | ||||||

| 7 | Choluteca | Choluteca | 86,179 | ||||||

| 8 | Danlí | El Paraíso | 64,976 | ||||||

| 9 | La Lima | Cortés | 62,903 | ||||||

| 10 | Villanueva | Cortés | 62,711 | ||||||

Religion

Although most Hondurans are nominally Catholic (which would be considered the main religion), membership in the Catholic Church is declining while membership in Protestant churches is increasing. The International Religious Freedom Report, 2008, notes that a CID Gallup poll reported that 51.4% of the population identified themselves as Catholic, 36.2% as evangelical Protestant, 1.3% claiming to be from other religions, including Muslims, Buddhists, Jews, Rastafarians, etc. and 11.1% do not belong to any religion or unresponsive. 8% reported as being either atheistic or agnostic. Customary Catholic church tallies and membership estimates 81% Catholic where the priest (in more than 185 parishes) is required to fill out a pastoral account of the parish each year.[120][121]

The CIA Factbook lists Honduras as 97% Catholic and 3% Protestant.[1] Commenting on statistical variations everywhere, John Green of Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life notes that: "It isn't that ... numbers are more right than [someone else's] numbers ... but how one conceptualizes the group."[122] Often people attend one church without giving up their "home" church. Many who attend evangelical megachurches in the US, for example, attend more than one church.[123] This shifting and fluidity is common in Brazil where two-fifths of those who were raised evangelical are no longer evangelical and Catholics seem to shift in and out of various churches, often while still remaining Catholic.[124]

Most pollsters suggest an annual poll taken over a number of years would provide the best method of knowing religious demographics and variations in any single country. Still, in Honduras are thriving Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist, Seventh-day Adventist, Lutheran, Latter-day Saint (Mormon) and Pentecostal churches. There are Protestant seminaries. The Catholic Church, still the only "church" that is recognized, is also thriving in the number of schools, hospitals, and pastoral institutions (including its own medical school) that it operates. Its archbishop, Cardinal Óscar Andrés Rodriguez Maradiaga, is also very popular with the government, other churches, and in his own church. Practitioners of the Buddhist, Jewish, Islamic, Baháʼí, Rastafari and indigenous denominations and religions exist.[125]

Health

Education

About 83.6% of the population are literate and the net primary enrollment rate was 94% in 2004.[126] In 2014, the primary school completion rate was 90.7%.[127] Honduras has bilingual (Spanish and English) and even trilingual (Spanish with English, Arabic, or German) schools and numerous universities.[128]

The higher education is governed by the National Autonomous University of Honduras which has centers in the most important cities of Honduras. Hondura was ranked 114th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[129]

Crime

Crime in Honduras is rampant and criminals operate with a high degree of impunity. Honduras has one of the highest national murder rates in the world; cities such as San Pedro Sula and the Tegucigalpa likewise have registered homicide rates among the highest in the world. The violence is associated with drug trafficking as Honduras is often a transit point, and with a number of urban gangs, mainly the MS-13 and the 18th Street gang. Homicide violence reached a peak in 2012 with an average of 20 homicides a day.[130] Official statistics from the Honduran Observatory on National Violence show Honduras's homicide rate was 60 per 100,000 in 2015 with the majority of homicide cases unprosecuted.[131] But as recently as 2017, organizations such as InSight Crime's show figures of 42 per 100,000 inhabitants,[132] a 26% drop from 2016 figures.

Highway assaults and carjackings at roadblocks or checkpoints set up by criminals with police uniforms and equipment occur frequently. Although reports of kidnappings of foreigners are not common, families of kidnapping victims often pay ransoms without reporting the crime to police out of fear of retribution, so kidnapping figures may be underreported.[131]

Violence in Honduras increased after Plan Colombia was implemented and after Mexican President Felipe Calderón declared the war against drug trafficking in Mexico.[133] Along with neighboring El Salvador and Guatemala, Honduras forms part of the Northern Triangle of Central America, which has been characterized as one of the most violent regions in the world.[134] As a result of crime and increasing murder rates, the flow of migrants from Honduras to the U.S. also went up. The rise in violence in the region has received international attention.

Roatan and the Bay Islands have lower crime rates than the Honduran mainland, which have been attributed to measures taken by government and business in 2014 to improve tourist safety.[131]

In the less populated region of Gracias a Dios, narcotics-trafficking is rampant and police presence is scarce. Threats against U.S. citizens by drug traffickers and other criminal organizations have resulted in the U.S. Embassy placing restrictions on the travel of U.S. officials through the region.[131]

Culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

Art

The most renowned Honduran painter is José Antonio Velásquez. Other important painters include Carlos Garay, and Roque Zelaya. Some of Honduras's most notable writers are Lucila Gamero de Medina, Froylán Turcios, Ramón Amaya Amador and Juan Pablo Suazo Euceda, Marco Antonio Rosa,[135] Roberto Sosa, Eduardo Bähr, Amanda Castro, Javier Abril Espinoza, Teófilo Trejo, and Roberto Quesada.

The José Francisco Saybe theater in San Pedro Sula is home to the Círculo Teatral Sampedrano (Theatrical Circle of San Pedro Sula)

Honduras has experienced a boom from its film industry for the past two decades. Since the premiere of the movie "Anita la cazadora de insectos" in 2001, the level of Honduran productions has increased, many collaborating with countries such as Mexico, Colombia, and the U.S. The most well known Honduran films are "El Xendra", "Amor y Frijoles", and "Cafe con aroma a mi tierra".

Cuisine

Honduran cuisine is a fusion of indigenous Lenca cuisine, Spanish cuisine, Caribbean cuisine and African cuisine. There are also dishes from the Garifuna people. Coconut and coconut milk are featured in both sweet and savory dishes. Regional specialties include fried fish, tamales, carne asada and baleadas.

Other popular dishes include: meat roasted with chismol and carne asada, chicken with rice and corn, and fried fish with pickled onions and jalapeños. Some of the ways seafood and some meats are prepared in coastal areas and in the Bay Islands involve coconut milk.

The soups Hondurans enjoy include bean soup, mondongo soup (tripe soup), seafood soups and beef soups. Generally these soups are served mixed with plantains, yuca, and cabbage, and served with corn tortillas.

Other typical dishes are the montucas or corn tamales, stuffed tortillas, and tamales wrapped in plantain leaves. Honduran typical dishes also include an abundant selection of tropical fruits such as papaya, pineapple, plum, sapote, passion fruit and bananas which are prepared in many ways while they are still green.

Media

At least half of Honduran households have at least one television. Public television has a far smaller role than in most other countries. Honduras's main newspapers are La Prensa, El Heraldo, La Tribuna and Diario Tiempo. The official newspaper is La Gaceta (Honduras).

Music

Punta is the main music of Honduras, with other sounds such as Caribbean salsa, merengue, reggae, and reggaeton all widely heard, especially in the north, and Mexican rancheras heard in the rural interior of the country. The most well known musicians are Guillermo Anderson and Polache. Banda Blanca is a widely known music group in both Honduras and internationally.

Celebrations

Some of Honduras's national holidays include Honduras Independence Day on 15 September and Children's Day or Día del Niño, which is celebrated in homes, schools and churches on 10 September; on this day, children receive presents and have parties similar to Christmas or birthday celebrations. Some neighborhoods have piñatas on the street. Other holidays are Easter, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, Day of the Soldier (3 October to celebrate the birth of Francisco Morazán), Christmas, El Dia de Lempira on 20 July,[136] and New Year's Eve.

Honduras Independence Day festivities start early in the morning with marching bands. Each band wears different colors and features cheerleaders. Fiesta Catracha takes place this same day: typical Honduran foods such as beans, tamales, baleadas, cassava with chicharrón, and tortillas are offered.

On Christmas Eve people reunite with their families and close friends to have dinner, then give out presents at midnight. In some cities fireworks are seen and heard at midnight. On New Year's Eve there is food and "cohetes", fireworks and festivities. Birthdays are also great events, and include piñatas filled with candies and surprises for the children.

La Ceiba Carnival is celebrated in La Ceiba, a city located in the north coast, in the second half of May to celebrate the day of the city's patron saint Saint Isidore. People from all over the world come for one week of festivities. Every night there is a little carnaval (carnavalito) in a neighborhood. On Saturday there is a big parade with floats and displays with people from many countries. This celebration is also accompanied by the Milk Fair, where many Hondurans come to show off their farm products and animals.

National symbols

The flag of Honduras is composed of three equal horizontal stripes. The blue upper and lower stripes represent the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. The central stripe is white. It contains five blue stars representing the five states of the Central American Union. The middle star represents Honduras, located in the center of the Central American Union.

The coat of arms was established in 1945. It is an equilateral triangle, at the base is a volcano between three castles, over which is a rainbow and the sun shining. The triangle is placed on an area that symbolizes being bathed by both seas. Around all of this an oval containing in golden lettering: "Republic of Honduras, Free, Sovereign and Independent".

The "National Anthem of Honduras" is a result of a contest carried out in 1914 during the presidency of Manuel Bonilla. In the end, it was the poet Augusto Coello that ended up writing the anthem, with German-born Honduran composer Carlos Hartling writing the music. The anthem was officially adopted on 15 November 1915, during the presidency of Alberto de Jesús Membreño.

The national flower is the famous orchid, Rhyncholaelia digbyana (formerly known as Brassavola digbyana), which replaced the rose in 1969. The change of the national flower was carried out during the administration of general Oswaldo López Arellano, thinking that Brassavola digbyana "is an indigenous plant of Honduras; having this flower exceptional characteristics of beauty, vigor and distinction", as the decree dictates it.

The national tree of Honduras was declared in 1928 to be simply "the Pine that appears symbolically in our Coat of Arms" (el Pino que figura simbólicamente en nuestro Escudo),[137] even though pines comprise a genus and not a species, and even though legally there's no specification as for what kind of pine should appear in the coat of arms either. Because of its commonality in the country, the Pinus oocarpa species has become since then the species most strongly associated as the national tree, but legally it is not so. Another species associated as the national tree is the Pinus caribaea.

The national mammal is the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), which was adopted as a measure to avoid excessive depredation.[clarification needed] It is one of two species of deer that live in Honduras. The national bird of Honduras is the scarlet macaw (Ara macao). This bird was much valued by the pre-Columbian civilizations of Honduras.

Folklore

Legends and fairy tales are paramount in Honduran culture. Lluvia de Peces (Rain of Fish) is an example of this. The legends of El Cadejo and La Llorona are also popular.

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in Honduras.[138] Honduras's first international competition began in 1921 at the Independence Centenary Games featuring neighboring countries in Central America.[139] The highest division of football is The Honduran National Professional Football League (Spanish: La Liga Nacional de Fútbol Profesional de Honduras), which was established in 1964.[140] The league is recognized on a continental level, as C.D. Olimpia–the only Honduran club to win the competition–won the CONCACAF Champions League in 1972 and 1988.[141][142] The Honduras national football team (Spanish: Selección de fútbol de Honduras) is considered one of the best nations in North America, as the country last won the CONCACAF Gold Cup in 1981 and placed third in 2013.[143][144] On a global scale, Honduras has competed in the FIFA World Cup three times in 1982, 2010, and 2014, although Los Catrachos have yet to win a game.[145][146][147]

Baseball is the second most popular sport in Honduras.[148] Honduras's first international competition began in 1950 in the Baseball World Cup, which was the most prestigious global competition at the time.[149] The country lacks a division in baseball, likely due to the absence of competition in international baseball since 1973.[citation needed] The Honduras national baseball team (Spanish: Selección de béisbol de Honduras) is shy of being a top ten nation in North and South America due to infrequent scheduling, although competition is consistent and growing at the youth level.[150][151] Inspiration at the youth level came from Mauricio Dubón being the first born and raised Honduran to start in Major League Baseball, who is currently competing today.[152]

All other sports tend to be minor at best, as Honduras has not won a medal in the Olympics and has not made notable results in other world championships yet.[153] However, Hondurans have consistently entered track & field and swimming games at the Summer Olympics since 1968 and 1984, respectively.[154] Occasionally, Honduras has competed in combat sports ranging from judo to boxing at the Summer Olympics as well.[155][156] Gender inequality in Honduras is present in the sports industry, as teams like the Honduras women's national football team (Spanish: Selección de fútbol de Honduras Femenina) has yet to qualify in global and continental tournaments and softball being nearly nonexistent in the country.[157][158]

See also

Notes

- ^ /hɒnˈdjʊərəs, -æs/ ;[6] Spanish: [onˈduɾas]

- ^ Spanish: República de Honduras

References

- ^ a b c d e "Honduras". The World Factbook. 5 January 2016. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Honduras". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Honduras)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Gini Index coefficient". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- ^ a b "Mosquito Coast". Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McSweeney, Kendra, et al. (2011). "Climate-Related Disaster Opens a Window of Opportunity for Rural Poor in Northeastern Honduras". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (13): 5203–5208. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5203M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014123108. JSTOR 41125677. PMC 3069189. PMID 21402909.

- ^ a b Merrill, Tim, ed. (1995). "War with El Salvador". Honduras. Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Human Development Report 2016: Human Development for Everyone" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Ruhl, J. Mark (1984). "Agrarian Structure and Political Stability in Honduras". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 26 (1): 33–68. doi:10.2307/165506. ISSN 0022-1937. JSTOR 165506. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2019 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "History of Honduras — Timeline". Office of the Honduras National Chamber of Tourism. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Davidson traces it to Herrera. Historia General de los Hechos de los Castellanos. Vol. VI. Buenos Aires: Editorial Guarania. 1945–1947. p. 24. ISBN 978-8474913323.

- ^ a b Davidson, William (2006). Honduras, An Atlas of Historical Maps. Managua: Fundacion UNO, Colección Cultural de Centro America Serie Historica, no. 18. p. 313. ISBN 978-99924-53-47-6.

- ^ Objetivos de desarrollo del milenio, Honduras 2010: tercer informe de país [Millennium Development Goals, Honduras 2010: Third Country Report] (PDF) (in Spanish). [Honduras]: Sistema de las Naciones Unidas en Honduras. 2010. ISBN 978-99926-760-7-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Danny Law (15 June 2014), Language Contact, Inherited Similarity and Social Difference: The story of linguistic interaction in the Maya lowlands, John Benjamins Publishing Company, p. 105

- ^ Boyd Dixon (1989). "A Preliminary Settlement Pattern Study of a Prehistoric Cultural Corridor: The Comayagua Valley, Honduras". Journal of Field Archaeology. 16 (3): 257–271. doi:10.2307/529833. JSTOR 529833.

- ^ Susan Toby Evans; David L. Webster (11 September 2013). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136801860. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Columbus and the History of Honduras". Office of the Honduras National Chamber of Tourism. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Perramon, Francesc Ligorred (1986). "Los primeros contactos lingüísticos de los españoles en Yucatán". In Miguel Rivera; Andrés Ciudad (eds.). Los mayas de los tiempos tardíos (PDF) (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Sociedad Española de Estudios Mayas. p. 242. ISBN 9788439871200. OCLC 16268597. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b Clendinnen, Inga (2003) [1988]. Ambivalent Conquests: Maya and Spaniard in Yucatan, 1517–1570 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0-521-52731-7. OCLC 50868309.

- ^ Sharer, Robert J.; Loa P. Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th ed.). Stanford, California, US: Stanford University Press. p. 758. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446.

- ^ Vera, Robustiano, ed. (1899). Apuntes para la Historia de Honduras [Notes on the History of Honduras] (in Spanish). Santiago: Santiago de Chile : Imp. de "El Correo,". Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Kilgore, Cindy; Moore, Alan (27 May 2014). Adventure Guide to Copan & Western Honduras. Hunter publishing. ISBN 9781588439222. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

Spanish conquistadores did not become interested in colonization of Honduras until the 1520s when Cristobal de Olid the first European colony in Triunfo de la Cruz in 1524. A previous expedition headed by Gil Gonzalez Davila ...

- ^ Newson, Linda (October 1982). "Labour in the Colonial Mining Industry of Honduras". The Americas. 39 (2): 185–203. doi:10.2307/981334. JSTOR 981334.

- ^ Newson, Linda (December 1987). The Cost of Conquest: Indian Decline in Honduras Under Spanish Rule: Dellplain Latin American Studies, No. 20. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0813372730.