Peloponnesian War

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (June 2022) |

| Peloponnesian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Peloponnesian war alliances at 431 BC. Orange: Athenian Empire and Allies; green: Spartan Confederacy. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Delian League (led by Athens) |

Peloponnesian League (led by Sparta) Supported by: Achaemenid Empire | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

At least 18,070 soldiers[1] unknown number of civilian casualties. | Unknown | ||||||||

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (Ancient Greek: Πόλεμος τῶν Πελοποννησίων, romanized: Pólemos tō̃n Peloponnēsíōn), was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided until the later intervention of the Persian Empire in support of Sparta. Led by Lysander, the Spartan fleet (built with Persian subsidies) finally defeated Athens which began a period of Spartan hegemony over Greece.

Historians have traditionally divided the war into three phases.[2][3] The first phase (431–421 BC) was named the Ten Years War, or the Archidamian War, after the Spartan king Archidamus II, who invaded Attica several times with the full hoplite army of the Peloponnesian League, the alliance network dominated by Sparta (then known as Lacedaemon). The Long Walls of Athens rendered this strategy ineffective, while the superior navy of the Delian League (Athens' alliance) raided the Peloponnesian coast to trigger rebellions within Sparta. The precarious Peace of Nicias was signed in 421 BC and lasted until 413 BC. Several proxy battles took place during this period, notably the battle of Mantinea in 418 BC, won by Sparta against an ad-hoc alliance of Elis, Mantinea (both former Spartan allies), Argos, and Athens. The main event was the Sicilian Expedition, between 415 and 413 BC, during which Athens lost almost all its navy in the attempt to capture Syracuse, an ally of Sparta.

The Sicilian disaster prompted the third phase of the war (413–404 BC), named the Decelean War, or the Ionian War, when the Persian Empire supported Sparta to recover the suzerainty of the Greek cities of Asia Minor, incorporated into the Delian League at the end of the Persian Wars. With Persian money, Sparta built a massive fleet under the leadership of Lysander, who won a streak of decisive victories in the Aegean Sea, notably at Aegospotamos, in 405 BC. Athens capitulated the following year and lost all its empire. Lysander imposed puppet oligarchies on the former members of the Delian League, including Athens, where the regime was known as the Thirty Tyrants. The Peloponnesian War was followed ten years later by the Corinthian War (394–386 BC), which, although it ended inconclusively, helped Athens regain its independence from Sparta.

The Peloponnesian War changed the ancient Greek world. Athens, the strongest city-state in Greece prior to the war, was reduced to a state of near-complete subjection, while Sparta became established as the leading power of Greece. The economic costs of the war were felt all across Greece, poverty became widespread in the Peloponnese, while Athens was devastated and never regained its pre-war prosperity.[4][5] The war also wrought subtler changes to Greek society, the conflict between democratic Athens and oligarchic Sparta, each of which supported friendly political factions within other states, made war a common occurrence in the Greek world. Ancient Greek warfare, originally a limited and formalized form of conflict, was transformed into an all-out struggle between city-states, complete with mass atrocities. Shattering religious and cultural taboos, devastating vast swathes of countryside, and destroying whole cities, the Peloponnesian War marked the dramatic end to the fifth century BC and the golden age of Greece.[6]

Historic sources

The main historical source for most of the war is the detailed account in The History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides. He states that he began writing his history as soon as the war broke out and took his information from first-hand accounts, including events he witnessed himself. An Athenian who fought in the early part of the war, Thucydides was exiled in 423 BC and settled in the Peloponnese, where he spent the rest of the war collecting sources and writing his history. Scholars regard Thucydides as reliable and neutral between the two sides.[7] A partial exception are the lengthy speeches he reports, which Thucydides admits are not accurate records of what was said, but his interpretation of the general arguments presented.[8] The narrative begins several years before the war, explaining why it began, then reports events year-by-year. The main limitation of Thucydides' work is that it is incomplete: the text ends abruptly in 411 BC, seven years before the conclusion of the war.

The account was continued by Xenophon, a younger contemporary, in the first book of his Hellenica. This directly follows Thucydides' final sentence and provides a similar record, on the topics of the war's conclusion and aftermath. Born in Athens, Xenophon spent his military career as a mercenary, fighting in the Persian Empire and for Sparta in Asia Minor, Thrace and Greece. Exiled from Athens for these actions, he retired to live in Sparta, where he wrote Hellenica around 40 years after the war had ended. His account is generally considered favourable to Sparta.[9]

A briefer account of the whole war is provided by the Sicilian historian Diodorus Siculus in books 12 and 13 of his Bibliotheca historica. Written in the first century BC, these books appear to be based heavily (possibly entirely) upon an earlier universal history by Ephorus, written in the century after the war, which is now lost.

The Roman-Greek historian Plutarch wrote biographies of four of the major commanders in the war (Pericles, Nicias, Alcibiades and Lysander) in his Parallel Lives. Plutarch's focus was on the character and morality of these men, but he does provide some details on the progress of the war that are not recorded elsewhere. Written in the first century AD, Plutarch based his work on earlier accounts which are now lost.

More limited information on the war is derived from epigraphy and archaeology, such as the walls of Amphipolis and grave of Brasidas, excavated in the 20th century. Some buildings and artworks produced during the war have survived, such as the Erechtheion temple and Grave Stele of Hegeso, both in Athens; these provide no information on military activity but do reflect civilian life during the war. Several plays by the Athenian Aristophanes were written and set during the war (particularly Peace and Lysistrata), but these are works of comedic fiction with little historical value.

Prelude

Thucydides summarised the situation before the war as: "The growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Lacedaemon, made war inevitable".[10] The nearly 50 years before the War had been marked by the development of Athens as a major power in the Mediterranean world. Its empire began as a small group of city-states, called the Delian League – from the island of Delos, on which they kept their treasury – that formed to ensure that the Greco-Persian Wars were over. After defeating the Second Persian invasion of Greece in the year 480 BC, Athens led the coalition of Greek city-states that continued the Greco-Persian Wars with attacks on Persian territories in the Aegean and Ionia. What ensued was a period which Thucydides called the Pentecontaetia, in which Athens increasingly became an empire,[11] carrying out an aggressive war against Persia and increasingly dominating other city-states. Athens brought under its control all of Greece except for Sparta and its allies, ushering in a period now called the Athenian Empire. By mid-century, the Persians had been driven out of the Aegean and had ceded control of vast territories to Athens. Athens had greatly increased its own power; a number of its formerly independent allies were reduced, over the course of the century, to the status of tribute-paying subject states of the Delian League. This tribute was used to fund a powerful fleet and, after the middle of the century, massive public works in Athens, causing resentment.[12]

Friction between Athens and the Peloponnesian states, including Sparta, began early in the Pentecontaetia. In the wake of the departure of the Persians from Greece, Sparta sent ambassadors to persuade Athens not to reconstruct their walls, but was rebuffed. Without the walls, Athens would have been defenseless against a land attack and subject to Spartan control.[13] According to Thucydides, although the Spartans took no action then, they "secretly felt aggrieved".[14] Conflict between the states flared up again in 465 BC, when a helot revolt broke out in Sparta. The Spartans summoned forces from all of their allies, including Athens, to help them suppress the revolt. Athens sent out a sizable contingent (4,000 hoplites), but upon its arrival, this force was dismissed by the Spartans, while those of all the other allies were permitted to remain. According to Thucydides, the Spartans did this out of fear that the Athenians would switch sides and support the helots; the offended Athenians repudiated their alliance with Sparta.[15] When the rebellious helots were finally forced to surrender and permitted to evacuate the state, the Athenians settled them at the strategic city of Naupaktos on the Gulf of Corinth.[16]

In 459 BC, there was a war between Spartan allies Megara and Corinth, which were neighbors of Athens. Athens took advantage of the war to make an alliance with Megara, giving Athens a critical foothold on the Isthmus of Corinth. A 15-year conflict, commonly known as the First Peloponnesian War, ensued, in which Athens fought intermittently against Sparta, Corinth, Aegina, and a number of other states. For a time during this conflict, Athens controlled not only Megara but also Boeotia. But at its end, a massive Spartan invasion of Attica forced Athens to cede the lands it had won on the Greek mainland, and Athens and Sparta recognized each other's right to control their respective alliance systems.[17] The war was officially ended by the Thirty Years' Peace, signed in the winter of 446/5 BC.[18]

Breakdown of peace

The Thirty Years' Peace was first tested in 440 BC, when Athens's powerful ally Samos rebelled from its alliance with Athens. The rebels quickly secured the support of a Persian satrap, and Athens faced the prospect of revolts throughout its empire. The Spartans, whose intervention would have been the trigger for a massive war to determine the fate of the empire, called a congress of their allies to discuss the possibility of war with Athens. Sparta's powerful ally Corinth was notably opposed to intervention, and the congress voted against war with Athens. The Athenians crushed the revolt, and peace was maintained.[19]

The more immediate events that led to war involved Athens and Corinth. After a defeat by their colony of Corcyra, a sea power that was not allied to either Sparta or Athens, Corinth began to build an allied naval force. Alarmed, Corcyra sought alliance with Athens. Athens discussed with both Corcyra and Corinth, and made a defensive alliance with Corcyra. At the Battle of Sybota, a small contingent of Athenian ships played a critical role in preventing a Corinthian fleet from capturing Corcyra. In order to uphold the Thirty Years' Peace, the Athenians were instructed not to intervene in the battle unless it was clear that Corinth would invade Corcyra. However, the Athenian ships participated in the battle, and the arrival of additional Athenian triremes was enough to dissuade the Corinthians from exploiting their victory, thus sparing much of the routed Corcyrean and Athenian fleet.[20]

Following this, Athens instructed Potidaea in the peninsula of Chalkidiki, a tributary ally of Athens but a colony of Corinth, to tear down its walls, send hostages to Athens, dismiss the Corinthian magistrates from office, and refuse the magistrates that Corinth would send in the future.[21] Outraged, the Corinthians encouraged Potidaea to revolt and assured them that they would ally with them should they revolt from Athens. During the subsequent Battle of Potidaea, the Corinthians unofficially aided Potidaea by sneaking contingents of men into the besieged city to help defend it. This directly violated the Thirty Years' Peace, which stipulated that the Delian League and the Peloponnesian League would respect each other's autonomy and internal affairs.

A further provocation was Athens in 433/2 BC imposing trade sanctions on Megarian citizens (once more a Spartan ally after the First Peloponnesian War). It was alleged that the Megarians had desecrated the Hiera Orgas. These sanctions, known as the Megarian decree, were largely ignored by Thucydides, but some modern economic historians have noted that forbidding Megara to trade with the prosperous Athenian empire would have been disastrous for the Megarans, and so have considered the sanctions a contributing causing of the war.[22] Historians who attribute responsibility for the war to Athens cite this event as the main cause.[23]

At the request of Corinth, the Spartans summoned members of the Peloponnesian League to Sparta in 432 BC, especially those who had grievances with Athens, to make their complaints to the Spartan assembly. This debate was also attended by an uninvited delegation from Athens, which also asked to speak, and became the scene of a debate between the Athenians and the Corinthians. Thucydides reports that the Corinthians condemned Sparta's inactivity until then, warning Sparta that if it remained passive, it would soon be outflanked and without allies.[24] In response, the Athenians reminded the Spartans of Athens's record of military success and opposition to Persia, warned them of confronting such a powerful state, and encouraged Sparta to seek arbitration as provided by the Thirty Years' Peace.[25] The Spartan king Archidamus II spoke against the war, but the opinion of the hawkish ephor Sthenelaidas prevailed in the Spartan ecclesia.[26] A majority of the Spartan assembly voted to declare that the Athenians had broken the peace, essentially declaring war.[27]

Archidamian War (431–421 BC)

The first years of the Peloponnesian war are known as the Archidamian War (431–421 BC), after Sparta's king Archidamus II.

Sparta and its allies, except for Corinth, were almost exclusively land-based, and able to summon large armies which were nearly unbeatable (thanks to the legendary Spartan forces). The Athenian Empire, although based in the peninsula of Attica, spread out across the islands of the Aegean Sea; Athens drew its immense wealth from tribute paid by these islands. Athens maintained its empire through naval power. Thus, the two powers were relatively unable to fight decisive battles.

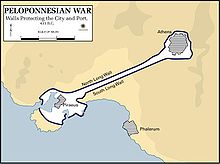

The Spartan strategy during the Archidamian War was to invade the land around Athens. While this invasion deprived Athenians of the productive land around their city, Athens maintained access to the sea, and did not suffer much. Many of the citizens of Attica abandoned their farms and moved inside the Long Walls, which connected Athens to its port of Piraeus. At the end of the first year of the war, Pericles gave his famous Funeral Oration (431 BC).

The Spartans also occupied Attica for periods of only three weeks at a time; in the tradition of earlier hoplite warfare, the soldiers were expected to go home to participate in the harvest. Moreover, Spartan slaves, known as helots, needed to be kept under control, and could not be left unsupervised for long. The longest Spartan invasion, in 430 BC, lasted just 40 days.

The Athenian strategy was initially guided by the strategos, or general, Pericles, who advised the Athenians to avoid open battle with the far more numerous and better trained Spartan hoplites, relying instead on the fleet. The Athenian fleet, the dominant Greek naval force, went on the offensive, winning at Naupactus. In 430 BC, an outbreak of a plague hit Athens. The plague ravaged the densely packed city, and in the long run, was a significant cause of its final defeat. The plague wiped out over 30,000 citizens, sailors and soldiers, including Pericles and his sons. Roughly one-third to two-thirds of the Athenian population died. Athenian manpower was correspondingly drastically reduced and even foreign mercenaries refused to hire themselves out to a city riddled with plague. The fear of plague was so widespread that the Spartan invasion of Attica was abandoned, their troops being unwilling to risk contact with the diseased enemy.

After the death of Pericles, the Athenians turned somewhat against his conservative, defensive strategy and to the more aggressive strategy of bringing the war to Sparta and its allies. Rising to particular importance in Athenian democracy at this time was Cleon, a leader of the hawkish elements of the Athenian democracy. Led militarily by a clever new general Demosthenes (not to be confused with the later Athenian orator Demosthenes), the Athenians managed some successes as they continued their naval raids on the Peloponnese. Athens stretched their military activities into Boeotia and Aetolia, quelled the Mytilenean revolt and began fortifying posts around the Peloponnese. One of these posts was near Pylos on a tiny island called Sphacteria, where the first war turned in Athens's favor. The post off Pylos exploited Sparta's dependence on the helots, slaves who worked the fields while its citizens trained to be soldiers. The Pylos post began attracting helot runaways. In addition, the fear of a revolt of helots emboldened by the nearby Athenians drove the Spartans to attack the post. Demosthenes outmaneuvered the Spartans in the Battle of Pylos in 425 BC and trapped a group of Spartan soldiers on Sphacteria as he waited for them to surrender. But weeks later he proved unable to finish them off. Instead, the inexperienced Cleon boasted in the Assembly that he could end the affair, and did win a great victory at the Battle of Sphacteria. In a shocking turn of events, 300 Spartan hoplites encircled by Athenian forces surrendered. The Spartan image of invincibility took significant damage. The Athenians jailed Sphacterian hostages in Athens and resolved to execute the captured Spartans if a Peloponnesian army invaded Attica again.

After these battles, the Spartan general Brasidas raised an army of allies and helots and marched the length of Greece to the Athenian colony of Amphipolis in Thrace. Amphipolis controlled several nearby silver mines whose that supplied much of the Athenian war fund. A force led by Thucydides was dispatched but arrived too late to stop Brasidas capturing Amphipolis; Thucydides was exiled for this, and, as a result, had conversations with both sides of the war which inspired him to record its history. Both Brasidas and Cleon were killed in Athenian efforts to retake Amphipolis (see Battle of Amphipolis). The Spartans and Athenians agreed to exchange the hostages for the towns captured by Brasidas, and signed a truce.

Peace of Nicias (421 BC)

With the death of Cleon and Brasidas, both zealous war hawks for their nations, the Peace of Nicias was able to last six years. However, it was a time of constant skirmishes in and around the Peloponnese. While the Spartans refrained from action themselves, some of their allies began to talk of revolt. They were supported in this by Argos, a powerful Peloponnesian state that had remained independent of Lacedaemon. With the support of the Athenians, the Argives forged a coalition of democratic states in the Peloponnese, including the powerful states of Mantinea and Elis. Early Spartan attempts to break up the coalition failed, and the leadership of the Spartan king Agis was called into question. Emboldened, the Argives and their allies, with the support of a small Athenian force under Alcibiades, moved to seize the city of Tegea, near Sparta.

The Battle of Mantinea was the largest land battle within Greece during the Peloponnesian War. The Lacedaemonians, with their neighbors the Tegeans, faced the combined armies of Argos, Athens, Mantinea, and Arcadia. In the battle, the allied coalition scored early successes, but failed to capitalize on them, which allowed the Spartan elite forces to defeat them. The result was a complete victory for the Spartans, which rescued their city from the brink of strategic defeat. The democratic alliance was broken up, and most of its members were reincorporated into the Peloponnesian League. With its victory at Mantinea, Sparta pulled itself back from the brink of utter defeat, and re-established its hegemony throughout the Peloponnese.

In the summer of 416 BC, during a truce with Sparta, Athens invaded the neutral island of Melos, and demanded that Melos ally with them against Sparta, or be destroyed. The Melians rejected this, so the Athenian army laid siege to their city and eventually captured it in the winter. After the city's fall, the Athenians executed all the adult men,[28] and sold the women and children into slavery.[29]

Sicilian Expedition (415–413 BC)

In the 17th year of the war, word came to Athens that one of their distant allies in Sicily was under attack from Syracuse, the main city of Sicily. The people of Syracuse were ethnically Dorian (as were the Spartans), while the Athenians, and their ally in Sicilia, were Ionian.

The Athenians felt obliged to help their ally. They also held visions, rallied on by Alcibiades, who ultimately led an expedition, of conquering all of Sicily. Syracuse was not much smaller than Athens, and conquering all of Sicily would bring Athens immense resources. In the final preparations for departure, the hermai (religious statues) of Athens were mutilated by unknown persons, and Alcibiades was charged with religious crimes. Alcibiades demanded that he be put on trial at once, so that he could defend himself before the expedition. However, the Athenians allowed Alcibiades to go on the expedition without being tried (many believed in order to better plot against him). After arriving in Sicily, Alcibiades was recalled to Athens for trial. Fearing that he would be unjustly condemned, Alcibiades defected to Sparta and Nicias was placed in charge of the mission. After his defection, Alcibiades claimed to the Spartans that the Athenians planned to use Sicily as a springboard for the conquest of all of Italy and Carthage, and to use the resources and soldiers from these new conquests to conquer the Peloponnese.

The Athenian force consisted of over 100 ships and some 5,000 infantry and light-armored troops. Cavalry was limited to about 30 horses, which proved to be no match for the large and highly trained Syracusan cavalry. Upon landing in Sicily, several cities immediately joined the Athenian cause. But instead of attacking, Nicias procrastinated and the campaigning season of 415 BC ended with Syracuse scarcely damaged. With winter approaching, the Athenians withdrew into their quarters and spent the winter gathering allies. The delay allowed Syracuse to request help from Sparta, who sent their general Gylippus to Sicily with reinforcements. Upon arriving, he raised a force from several Sicilian cities, and went to the relief of Syracuse. He took command of the Syracusan troops, and in a series of battles defeated the Athenian forces, and prevented them from invading the city.

Nicias then sent word to Athens asking for reinforcements. Demosthenes was chosen and led another fleet to Sicily, joining his forces with those of Nicias. More battles ensued and again, the Syracusans and their allies defeated the Athenians. Demosthenes argued for a retreat to Athens, but Nicias at first refused. After additional setbacks, Nicias seemed to agree to a retreat until a bad omen, in the form of a lunar eclipse, delayed withdrawal. The delay was costly and forced the Athenians into a major sea battle in the Great Harbor of Syracuse. The Athenians were thoroughly defeated. Nicias and Demosthenes marched their remaining forces inland in search of friendly allies. The Syracusan cavalry rode them down mercilessly, eventually killing or enslaving all who were left of the mighty Athenian fleet.

The Second War (413–404 BC)

The Lacedaemonians were not content with simply sending aid to Sicily; they also resolved to take the war to the Athenians. On the advice of Alcibiades, they fortified Decelea, near Athens, and prevented the Athenians from making use of their land year round. The fortification of Decelea prevented overland supplies to Athens, and forced all supplies to be brought in by sea at greater expense. More significantly, the nearby silver mines were totally disrupted, with as many as 20,000 Athenian slaves freed by the Spartan hoplites at Decelea. With the treasury and emergency reserve of 1,000 talents dwindling, the Athenians were forced to demand even more tribute from her subject allies, further increasing tensions and the threat of rebellion within the Empire.

Corinth, Sparta, and others in the Peloponnesian League sent more reinforcements to Syracuse, to drive off the Athenians; but instead of withdrawing, the Athenians sent another hundred ships and another 5,000 troops to Sicily. Under Gylippus, the Syracusans and their allies decisively defeated the Athenians on land; and Gylippus encouraged the Syracusans to build a navy, which defeated the Athenian fleet when they tried to withdraw. The Athenian army tried to withdraw overland to friendlier Sicilian cities, but was divided and defeated. The entire Athenian fleet was destroyed, and virtually the entire Athenian army was sold into slavery.

Following the defeat of the Athenians in Sicily, it was widely believed that the end of the Athenian Empire was at hand. Their treasury was nearly empty, its docks were depleted, and many of the Athenian youth were dead or imprisoned in a foreign land.

Athens recovers

After the destruction of the Sicilian Expedition, Lacedaemon encouraged the revolt of Athens's tributary allies, and indeed, much of Ionia rose in revolt. The Syracusans sent their fleet to the Peloponnesians, and the Persians decided to support the Spartans with money and ships. Revolt and faction threatened in Athens itself.

The Athenians managed to survive for several reasons. First, their foes lacked initiative. Corinth and Syracuse were slow to bring their fleets into the Aegean, and Sparta's other allies were also slow to furnish troops or ships. The Ionian states that rebelled expected protection, and many rejoined the Athenian side. The Persians were slow to send promised funds and ships, frustrating battle plans.

At the start of the war, the Athenians had prudently put aside some money and 100 ships that were to be used only as a last resort.

These ships were then released, and served as the core of the Athenians' fleet throughout the rest of the war. An oligarchical revolution occurred in Athens, in which a group of 400 seized power. Peace with Sparta might have been possible, but the Athenian fleet, now based on the island of Samos, refused the change. In 411 BC, this fleet engaged the Spartans at the Battle of Syme. The fleet appointed Alcibiades their leader, and continued the war in Athens's name. Their opposition led to the reinstitution of a democratic government in Athens within two years.

Alcibiades, while condemned as a traitor, still carried weight in Athens. He prevented the Athenian fleet from attacking Athens; instead, he helped restore democracy by more subtle pressure. He also persuaded the Athenian fleet to attack the Spartans at the battle of Cyzicus in 410. In the battle, the Athenians obliterated the Spartan fleet, and succeeded in re-establishing the financial basis of the Athenian Empire.

Between 410 and 406, Athens won a continuous string of victories, and eventually recovered large portions of its empire. All of this was due, in no small part, to Alcibiades.

Achaemenid's support for Sparta (414–404 BC)

From 414 BC, Darius II, ruler of the Achaemenid Empire had started to resent increasing Athenian power in the Aegean. He had his satrap Tissaphernes make alliance with Sparta against Athens. In 412 BC, this led to the Persian reconquest of most of Ionia.[31] Tissaphernes also helped fund the Peloponnesian fleet.[32][33]

Facing the resurgence of Athens, from 408 BC, Darius II decided to continue the war against Athens and give stronger support to the Spartans. He sent his son Cyrus the Younger into Asia Minor as satrap of Lydia, Phrygia Major and Cappadocia, and general commander (Karanos, κἀρανος) of the Persian troops.[34] There, Cyrus allied with the Spartan general Lysander. In him, Cyrus found a man willing to help him become king, just as Lysander himself hoped to become absolute ruler of Greece by the aid of the Persian prince. Thus, Cyrus put all his means at the disposal of Lysander in the Peloponnesian War. When Cyrus was recalled to Susa by his dying father Darius, he gave Lysander the revenues from all of his cities of Asia Minor.[35][36][37]

Cyrus the Younger would later obtain the support of the Spartans in return, after having asked them "to show themselves as good friend to him, as he had been to them during their war against Athens", when he led his own expedition to Susa in 401 BC in order to topple his brother, Artaxerxes II.[38]

The Athenian defeat

The faction hostile to Alcibiades triumphed in Athens following a minor Spartan victory by their skillful general Lysander at the naval battle of Notium in 406 BC. Alcibiades was not re-elected general by the Athenians and he exiled himself from the city. He would never again lead Athenians in battle. Athens won the naval battle of Arginusae. The Spartan fleet under Callicratidas lost 70 ships and the Athenians lost 25 ships. But, due to bad weather, the Athenians were unable to rescue their stranded crews or finish off the Spartan fleet. Despite their victory, these failures caused outrage in Athens and led to a controversial trial. The trial resulted in the execution of six of Athens's top naval commanders. Athens's naval supremacy would now be challenged without several of its most able military leaders and a demoralized navy.

Unlike some of his predecessors, the new Spartan general, Lysander, was not a member of the Spartan royal families and was also formidable in naval strategy; he was an artful diplomat, who had even cultivated good personal relationships with the Achaemenid prince Cyrus the Younger, son of Emperor Darius II. Seizing its opportunity, the Spartan fleet sailed at once to the Dardanelles, the source of Athens's grain. Threatened with starvation, the Athenian fleet had no choice but to follow. Through cunning strategy, Lysander totally defeated the Athenian fleet, in 405 BC, at the Battle of Aegospotami, destroying 168 ships. Only 12 Athenian ships escaped, and several of these sailed to Cyprus, carrying the strategos (general) Conon, who was anxious not to face the judgment of the Assembly.

Facing starvation and disease from the prolonged siege, Athens surrendered in 404 BC, and its allies soon surrendered as well. The democrats at Samos, loyal to the bitter last, held on slightly longer, and were allowed to flee with their lives. The surrender stripped Athens of its walls, its fleet, and all of its overseas possessions. Corinth and Thebes demanded that Athens should be destroyed and all its citizens should be enslaved. However, the Spartans announced their refusal to destroy a city that had done a good service at a time of greatest danger to Greece, and took Athens into their own system. Athens was "to have the same friends and enemies" as Sparta.[43]

Aftermath

The overall effect of the war in Greece proper was to replace the Athenian Empire with a Spartan empire. After the battle of Aegospotami, Sparta took over the Athenian empire and kept all its tribute revenues for itself; Sparta's allies, who had made greater sacrifices in the war than had Sparta, got nothing.[31]

For a short time, Athens was ruled by the Thirty Tyrants, a reactionary regime set up by Sparta. In 403 BC, the oligarchs were overthrown and a democracy was restored by Thrasybulus.

Although the hegemony of Athens was broken, the Attic city completed the recovery of its autonomy in the Corinthian War and continued to play an active role in Greek politics. Sparta was later defeated by Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC. A few decades later, the rivalry between Athens and Sparta ended when Macedonia became the most powerful entity in Greece and Philip II of Macedon unified all of the Greek world except Sparta, which was later subjugated by Philip's son Alexander in 331 BC.[44]

A symbolic peace treaty was signed by the mayors of modern Athens and Sparta 2,500 years after the war ended, on March 12, 1996.[45]

Citations

- ^ Barry Strauss: Athens After the Peloponnesian War: Class, Faction and Policy 403–386 B.C., New York 2014, p. 80.

- ^ "Thucydides and the Peloponnesian War". academic.mu.edu. Retrieved 2023-07-31.

- ^ "What History's Biggest Wars Teach Us About Leading in Peace". HBS Working Knowledge. 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2023-07-31.

- ^ Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, 488.

- ^ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 528–33.

- ^ Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, Introduction xxiii–xxiv.

- ^ Morley 2021, page 43, "widespread conviction that Thucydides was an especially reliable, objective, and trustworthy reporter of information".

- ^ Morley 2021, page 43, "Even more problematic are the speeches that he put into the mouths of important individuals, while admitting the impossibility of recording them verbatim".

- ^ Gatto, Martina. "Review of: Xenophon and Sparta". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. ISSN 1055-7660.

several deceptive passages in the Hellenika benefit the Spartans' reputation

- ^ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 1.23

- ^ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 371

- ^ Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, 8

- ^ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.89–93

- ^ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.92.1

- ^ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.102

- ^ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.103

- ^ Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, 16–18

- ^ In the Hellenic calendar, years ended at midsummer; as a result, some events cannot be dated to a specific year of the modern calendar.[clarification needed]

- ^ Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, 23–24

- ^ Thucydides, Book I, 49–50

- ^ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 1.56

- ^ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 454–56

- ^ Buckley Aspects of Greek History, 319–22

- ^ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.67–71

- ^ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.73–75

- ^ Ste. Croix, Origins of the Peloponnesian War, p. 201.

- ^ Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, 45.

- ^ Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War, 116

- ^ Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War, 5.116

- ^ Rollin, Charles (1851). The Ancient History of the Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Grecians, and Macedonians. W. Tegg and Company. p. 110.

- ^ a b Bury, J. B.; Meiggs, Russell (1956). A history of Greece to the death of Alexander the Great. London: Macmillan. pp. 397, 540.

- ^ "The winter following Tissaphernes put Iasus in a state of defence, and passing on to Miletus distributed a month's pay to all the ships as he had promised at Lacedaemon, at the rate of an Attic drachma a day for each man." in Perseus Under Philologic: Thuc. 8.29.1. Archived from the original on 2020-09-27. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- ^ Harrison, Cynthia (2002). "Numismatic Problems in the Achaemenid West: The Undue Modern Influence of 'Tissaphernes'". Numismatic Problems in the Achaemenid West: The Undue Modern Influence of 'Tissapherness'. pp. 301–19. doi:10.1163/9789004350908_018. ISBN 978-90-04-35090-8.

- ^ Mitchell, John Malcolm (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–76, see page 75.

the whole position was changed by the appointment of Cyrus the Younger as satrap of Lydia, Greater Phrygia and Cappadocia. His arrival coincided with the appointment of Lysander (c. Dec. 408) as Spartan admiral

- ^ "He then assigned to Lysander all the tribute which came in from his cities and belonged to him personally, and gave him also the balance he had on hand; and, after reminding Lysander how good a friend he was both to the Lacedaemonian state and to him personally, he set out on the journey to his father." in Xenophon, Hellenica 2.1.14.

- ^ Xenophon. Tr. H. G. Dakyns. Anabasis I.I. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Plutarch. Ed. by A.H. Clough. "Lysander", Plutarch's Lives. 1996. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Brownson, Carlson L. (Carleton Lewis) (1886). Xenophon;. Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press. pp. I-2–22.

- ^ Isocrates, Concerning the Team of Horses, 16.40

- ^ Peck, H. T. Harper's Dictionary of Classical Antiquities.

- ^ Smith, W. New Classical Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography. p. 39.

- ^ Plutarch, Alcibiades, 39.

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica, 2.2.20,404/3

- ^ Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (2010). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley & Sons. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- ^ "Athens, Sparta sign peace pact". United Press International. March 12, 1996.

General and cited references

Classical authors

- Aristophanes, Lysistrata.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica.

- Herodotus, Histories.

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, Moralia.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War.

- Xenophon, Hellenica.

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives (Pericles, Alcibiades, Lysander).

Modern authors

- Bagnall, Nigel. The Peloponnesian War: Athens, Sparta, And The Struggle For Greece. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0-312-34215-2).

- Cawkwell, George. Thucydides and the Peloponnesian War. London: Routledge, 1997 (hardcover, ISBN 0-415-16430-3; paperback, ISBN 0-415-16552-0).

- Hanson, Victor Davis. A War Like No Other: How the Athenians and Spartans Fought the Peloponnesian War. New York: Random House, 2005 (hardcover, ISBN 1-4000-6095-8); New York: Random House, 2006 (paperback, ISBN 0-8129-6970-7).

- Heftner, Herbert. Der oligarchische Umsturz des Jahres 411 v. Chr. und die Herrschaft der Vierhundert in Athen: Quellenkritische und historische Untersuchungen. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2001 (ISBN 3-631-37970-6).

- Hutchinson, Godfrey. Attrition: Aspects of Command in the Peloponnesian War. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Tempus Publishing, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 1-86227-323-5).

- Kagan, Donald:

- The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1969 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8014-0501-7); 1989 (paperback, ISBN 0-8014-9556-3).

- The Archidamian War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1974 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8014-0889-X); 1990 (paperback, ISBN 0-8014-9714-0).

- The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1981 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8014-1367-2); 1991 (paperback, ISBN 0-8014-9940-2).

- The Fall of the Athenian Empire. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8014-1935-2); 1991 (paperback, ISBN 0-8014-9984-4).

- The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking, 2003 (hardcover, ISBN 0-670-03211-5); New York: Penguin, 2004 (paperback, ISBN 0-14-200437-5); a one-volume version of his earlier tetralogy.

- Kallet, Lisa. Money and the Corrosion of Power in Thucydides: The Sicilian Expedition and its Aftermath. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001 (hardcover, ISBN 0-520-22984-3).

- Kirshner, Jonathan. 2018. "Handle Him with Care: The Importance of Getting Thucydides Right". Security Studies.

- Krentz, Peter. The Thirty at Athens. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1982 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8014-1450-4).

- Morley, Neville (13 September 2021). "Thucydides Legacy in Grand Strategy". In Balzacq, Thierry; Krebs, Ronald R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Grand Strategy. Oxford University Press. pp. 41–56. ISBN 978-0-19-257662-0.

- G. E. M. de Ste. Croix, The Origins of the Peloponnesian War, London, Duckworth, 1972. ISBN 0-7156-0640-9

- The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War, edited by Robert B. Strassler. New York: The Free Press, 1996 (hardcover, ISBN 0-684-82815-4); 1998 (paperback, ISBN 0-684-82790-5).

- Roberts, Jennifer T. The Plague of War: Athens, Sparta, and the Struggle for Ancient Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017 (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-19-999664-3

External links

- Mitchell, John Malcolm (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). pp. 71–76.

- LibriVox: The History of the Peloponnesian War (Public Domain Audiobooks in the US – 20:57:23 hours, at least 603.7 MB)

- Richard Crawley, The History of the Peloponnesian War (translation of Thukydides's books – in Project Gutenberg)

- Peloponnesian war

- Peloponnesian war on Lycurgus.org (archived 29 August 2016)