Pataliputra capital

| Pataliputra capital | |

|---|---|

Pataliputra palace capital (front and left-side view), early Maurya Empire period, 3rd century BCE. Another modern photograph of the capital. | |

| Material | Unpolished buff sandstone |

| Size | Height: 85 cm Width: 123 cm Weight: 1,800 lbs (900 kg) |

| Period/culture | 3rd Century BCE |

| Discovered | 25°36′07″N 85°10′48″E |

| Place | Bulandi Bagh, Pataliputra, India. |

| Present location | Patna Museum, India |

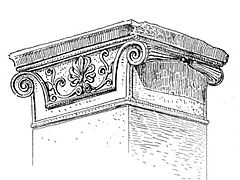

The Pataliputra capital is a monumental rectangular capital with volutes and Classical Greek designs, that was discovered in the palace ruins of the ancient Mauryan Empire capital city of Pataliputra (modern Patna, northeastern India). It is dated to the 3rd century BCE.

Discovery

[edit]

The monumental capital was discovered in 1895 at the royal palace in Pataliputra, India, in the area of Bulandi Bagh in Patna, by archaeologist L.A. Waddell in 1895. It was found at a depth of around 12 feet (3.7 meters), and dated to the reign of Ashoka or soon after, to the 3rd century BCE.[2] The discovery was first reported in Waddell's book "Report on the excavations at Pataliputra (Patna)".[3] "The capital is currently on display in the Patna Museum.[4]

Construction

[edit]The capital is made of unpolished buff sandstone. It is quite massive, with a length of 49 inches (1.2 meters), and a height of 33.5 inches (0.85 meters).[2] It weighs approximately 1,800 lbs (900 kg). During the excavations it was found next to a thick ancient wall and a brick pavement.[5]

The Pataliputra capital is generally dated to the early Maurya Empire period, 3rd century BCE. This would correspond to the reign of Chandragupta, his son Bindusara or his grandson Ashoka, who are all known to have welcomed Greek ambassadors at their court (respectively Megasthenes, Deimachus and Dionysius), who may well have come to Pataliputra with presents and craftsmen as suggested by classical sources.[6][7] The Indo-Greeks again possibly had a very direct presence in Pataliputra about a century later, circa 185 BCE, when they may have captured the city, although briefly, from the Sungas after the fall of the Maurya Empire.[8][9][10]

Design content

[edit]

The top is made of a band of rosettes, eleven in total for the fronts and four for the sides. Below that is a band of bead and reel pattern, then under it a band of waves, generally right-to-left, except for the back where they are left-to-right. Further below is a band of egg-and-dart pattern, with eleven "tongues" or "eggs" on the front, and only seven on the back. Below appears the main motif, a flame palmette, growing among pebbles.

The front and the back of the Pataliputra capital are both highly decorated, although the back has a few differences and is slightly coarser in design. The waves on the back are left-to-right, that is reverse of the waves on the front. Also, the back only has seven "eggs" in the egg-and-dart band (4th decorative band from the top), compared to eleven for the front. Lastly, the bottom pebble design is simpler on the back, with less pebbles being shown, and a small plinth or band visually supports them.[11]

Influences

[edit]Hellenistic style

[edit]

The capital is decorated with Classical Greek designs, such as the row of repeating rosettes, the ovolo, the bead and reel moulding, the wave-like scrolls as well as the central flame palmette and the volutes with central rosettes. It has been described as quasi-Ionic,[12] displaying definite Near Eastern influence,[13] or simply Greek in design and origin.[14]

The Archaeological Survey of India, an Indian government agency attached to the Ministry of Culture that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural monument in India, straightforwardly describes it as "a colossal capital in the Hellenistic style".[15]

The Pataliputra capital may reflect the influence of the Seleucid Empire or the neighboring Greco-Bactrian kingdom on early India sculptural art. In particular the city of Ai-Khanoum being located at the doorstep of India, interacting with the Indian subcontinent, and having a rich Hellenistic culture, was in a unique position to influence Indian culture as well. It is considered that Ai-Khanoum may have been one of the primary actors in transmitting Western artistic influence to India, for example in the creation of the manufacture of the quasi-Ionic Pataliputra capital or the floral friezes of the pillars of Ashoka, all of which were posterior to the establishment of Ai-Khanoum.[16] The scope of adoption goes from designs such as the bead and reel pattern, the central flame palmette design and a variety of other moldings, to the lifelike rendering of animal sculpture and the design and function of the Ionic anta capital in the palace of Pataliputra.[16]

-

The "flame palmette" design is well attested from Ai Khanoum, Afghanistan, 3rd-2nd century BCE.

-

Greek frieze designs: Top: Kyanos frieze from Tiryns. Bottom: Frieze of the Erechtheion in Athens (4th century BCE).

-

Persian capital with lotus capital and multiples volutes, Persepolis.

-

Persian frieze designs at Persepolis.

Achaemenid influence

[edit]Achaemenid influence has also been noted, especially in relation to the general shape, and the capital has been called a "Persianizing capital, complete with stepped impost, side volutes and central palmettes", which may be the result of the formative influence of craftsmen from Persia following the disintegration of the Achaemenid Empire after the conquests of Alexander the Great.[17] Some authors have remarked that the architecture of the city of Pataliputra seems to have had many similarities with Persian cities of the period.[18]

These authors stress that they are no known precedents in India (baring the hypothetical possibility of now-lost wooden structures), and that therefore the formative influence must have come from the neighbouring Achaemenid Empire.[17]

Hellenistic anta capital

[edit]However, according to art historian John Boardman, everything in the capital goes back to Greek influence: the "pilaster capitals with Greek florals and a form which is of Greek origin go back to Late Archaic."[19]

Anta capital

[edit]

For him, the Pataliputra capital is an anta capital (a capital at the top of the front edge of a wall), with Greek shape and Greek decorations.[21] The general shape of flat, slaying capital is well known among Classical anta capitals, and the rolls or volutes on the side are also a common feature, although more generally located at the top end of the capital.[22] He gives several examples of Greek anta capitals of similar designs from the Late Archaic period.[16]

Volutes and horizontal moldings

[edit]This type of anta capital with side volutes are considered as belonging to the Ionic order, starting from the archaic period. They are generally characterized by various moldings on the front, arranged in a rather flat manner in order not to protrude from the wall, with superposed volutes on curved sides broadening upwards.[23]

Central "flame palmette" design

[edit]The central motif of the Pataliputra capital is the flame palmette, the first appearance of which goes back to the floral akroteria of the Parthenon (447–432 BCE),[24] and slightly later at the Temple of Athena Nike,[25] and which spread to Asia Minor in the 3rd century BCE, and can be seen at the doorstep of India in Ai-Khanoum from around 280 BCE, in antefix and mosaic designs.[16]

| Central "flame palmette" designs in Greek art | |

| |

Construction

[edit]Structure as a pillar capital

[edit]

Since both sides of the Pataliputra capital are decorative (there is no blank side corresponding to a wall abutment), it is normally not structurally an anta capital, but rather a pile or pillar capital: the capital of an independent supporting column of square, rectangular or possibly round section.[26] Such capitals, if set on a square column, typically retain the design of an anta capital, but are decorated in all directions, whereas an anta capital is only decorated on the three sides that do not connect to the wall. If set on a round column such as one similar to a pillar of Ashoka, an intermediary piece of round section would be placed between the pillar and the capital, such as a lotus-shaped bulbus capital as those seen on the Ashoka pillars. Rather similar arrangements can be seen, for example, at the Ajanta cave. The Pataliputra capital has two holes on the top, which would imply a mode of fixation with a structural element overhead.[27]

Parallel with Bharhut pillar capitals

[edit]

According to architectural historian Dr. Christopher Tadgell, the Pataliputra capital is similar to the capitals which are visible in the reliefs of Sanchi and Bharhut, dated to the 2nd century BCE.[28] The Bharhut pillars are formed of a cylindrical or octagonal shaft, a bell capital and a crowning capital of trapezoid shape crisscrossed with incisions to achieve a decorative illusion (or a floral composition in more detailed examples), and often ended with a volute in each top corner. To him, the main characteristic of the Pataliputra capital would be that it has vertically arranged volutes, and clear motifs of west-Asiatic origin.[28]

An actual Bharhut capital, used to support the main Bharhut gateway, and presently in the Kolkota Indian Museum, uses a similar, if more complex arrangement, with four joined pillars instead of one, and incumbent lions on the top, sitting around a central crowning capital which has much similarity in design to the Pataliputra capital, complete with central palmette design, rosettes, and bead and reel motifs.[29]

Location in Pataliputra

[edit]

The site where the Pataliputra capital was excavated is marked by Waddell as the top-right corner of the area known today as Bulandi Bagh, northwest of the main excavation site.[30]

According to the reconstitution of the city of Pataliputra by Prof. Dr. Dieter Schlingloff, the pillared hall discovered at the other excavation site of Kumhrar was located outside of the city wall, on the banks of the former Sona river (called Erannoboas by Megasthenes). It is located about 400 meters to the South of the portions of the wooden palissade that have been excavated, and just north of the former banks of the Sona river. Therefore, the pillared hall could not have been the Mauryan palace, but rather "a pleasure hall outside the city walls".[31]

By the same reconstitution, the site of Bulandi Bagh where the Pataliputra capital was found, straddles the old wooden city palissades, so that the Pataliputra capital was probably located in a stone structure just inside the old city palissade, or possibly on a stone portion or a stone gate of the palissade itself.[32]

Later variations

[edit]Hellenistic designs in the Pillars of Ashoka

[edit]

The designs used in the Pataliputra capital are echoed by other known examples of Maurya architecture, especially the pillars of Ashoka. Many of these design elements can also be found in the decoration of the animal capitals of the Pillars of Ashoka, such as the palmettes or rosette designs. Various foreign influences have been described in the design of these capitals.[33] The animal on top of a lotiform capital reminds of Achaemenid column shapes. The abacus also often seems to display a strong influence of Greek art: in the case of the Rampurva bull or the Sankassa elephant, it is composed of honeysuckles alternated with stylized palmettes and small rosettes, as well as rows of beads and reels.[34] A similar kind of design can be seen in the frieze of the lost capital of the Allahabad pillar, as well as the Diamond throne built by Ashoka in Bodh Gaya.

Evolution of the Indian load-bearing pillar capital

[edit]4th-3rd c. BCE

2nd c. BCE

1st c. BCE/CE

1st c. BCE/CE

Similarities have been found in the designs of the capitals of various areas of northern India from the time of Ashoka to the time of the Satavahanas at Sanchi: particularly between the Pataliputra capital at the Mauryan Empire capital of Pataliputra (3rd century BCE), the pillar capitals at the Sunga Empire Buddhist complex of Bharhut (2nd century BCE), and the pillar capitals of the Satavahanas at Sanchi (1st centuries BCE/CE).[28]

The earliest known example in India, the Pataliputra capital (3rd century BCE) is decorated with rows of repeating rosettes, ovolos and bead and reel mouldings, wave-like scrolls and side volutes with central rosettes, around a prominent central flame palmette, which is the main motif. These are quite similar to Classical Greek designs, and the capital has been described as quasi-Ionic.[12][13] Greek influence,[14] as well as Persian Achaemenid influence have been suggested.[17]

The Sarnath capital is a pillar capital discovered in the archaeological excavations at the ancient Buddhist site of Sarnath.[35] The pillar displays Ionic volutes and palmettes.[36][37] It has been variously dated from the 3rd century BCE during the Mauryan Empire period,[38][35] to the 1st century BCE, during the Sunga Empire period.[36] One of the faces shows a galopping horse carrying a rider, while the other face shows an elephant and its mahaut.[36]

The pillar capital in Bharhut, dated to the 2nd century BCE during the Sunga Empire period, also incorporates many of these characteristics,[39][40] with a central anta capital with many rosettes, beads-and-reels, as well as a central palmette design.[28][41][42] Importantly, recumbent animals (lions, symbols of Buddhism) were added, in the style of the pillars of Ashoka.

The Sanchi pillar capital is keeping the general design, seen at Bharhut a century earlier, of recumbent lions grouped around a central square-section post, with the central design of a flame palmette, which started with the Pataliputra capital. However, the design of the central post is now simpler, with the flame palmette taking all the available room.[43] Elephants were later used to adorn the pillar capitals (still with the central palmette design), and lastly, Yakshas (here the palmette design disappears).

Ionic capitals

[edit]

Another capital in India has been identified as having the same compositional structure as the Pataliputra capital, the Sarnath capital. It is from Sarnath, at a distance of 250 km from Pataliputra. This other capital is also said to be from the Mauryan period. It is, together with the Pataliputra capital, considered as "stone brackets or capitals suggestive of the Ionic order".[44]

This capital is smaller in size however, at 33 cm high, and 63 cm wide when complete.[45] A similar capital with an elephant as the central motif has also been found in Sarnath.

A pillar capital in Bharhut,[46] dated to the 2nd century BCE during the Sunga Empire period, is an amalgam of the lions of the Pillars of Ashoka and a central anta capital with many Hellenistic elements (rosettes, beads-and-reels), as well as a central palmette design similar to that of the Pataliputra capital.[47][41] Monumental capitals with a central palmette design can still be found several centuries later in examples such as the Mathura lion capital (1st century CE).

A later capital found in Mathura dating to the 2nd or 3rd century (Kushan period) displays a central palmettes with side volutes in a style described as "Ionic", in the same kind of composition as the Pataliputra capital but with a coarser rendering. (photograph).[48]

Indo-Corinthian capitals

[edit]Right image: An Indo-Corinthian capital with a palmette and the Buddha at its centre, 3-4th century, Gandhara.

The Corinthian order later became overwhelmingly popular in the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, during the first centuries of our era. Various designs involving central palmettes with volutes are closer to the later Greek Corinthian anta or pilaster capital. Many such examples of Indo-Corinthian capitals can be found in the art of Gandhara.

Later Indian pillars

[edit]-

Pillar capital arrangement with round column and capital with rectangular section at Ajanta Caves.

-

Temple 17 at Sanchi: a Gupta period tetrastyle prostyle temple with pillar capital arrangement of Classical appearance. 5th century CE[49]

Implications

[edit]

The existence of such an Hellenistic capital so far east in the capital of the Maurya Empire suggests at the very least the presence of a Greek or Greek-inspired stone structure in the city. Although Pataliputra was originally built of wood, various accounts describe Ashoka as a remarkable builder of stone buildings, and he is known for certain to have built many stone pillars.[50][51] Ashoka is often credited with the beginning of stone architecture in India, possibly following the introduction of stone-building techniques by the Greeks after Alexander the Great[52] (a Greek ambassador named Dionysius is reported to have been at the court of Ashoka, sent by Ptolemy II Philadelphus[53]). Before Ashoka's time, buildings were probably built in non-permanent material, such as wood, bamboo or thatch.[52][54] Ashoka may have rebuilt his palace in Pataliputra by replacing wooden material by stone,[50] and may also have used the help of foreign craftmen.[51]

The 4th century Chinese pilgrim Fa-Hien also commented admiringly on the remains of the palace of Ashoka in Pataliputra:

It was the work not of men but of spirits which piled up the stones, reared the walls and gates, and executed elegant carvings and in-laid sculptured works in a way which no human hand of this world could accomplish.[55]

The influence of Greek art is also well attested in some of the Pillars of Ashoka, such as the Rampurva capital with its Hellenistic floral scrolls. It is also known that Ashoka redacted some of his stone edicts in excellent Greek in Kandahar, on the doorstep to the neighboring Seleucid Empire and Greco-Bactrian kingdom: the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription and the Kandahar Greek Edict of Ashoka.

The presence in Pataliputra of Greek diplomats such as Megasthenes is well known, but the capital raises the possibility of simultaneous artistic influence and even the possibility that foreign artists were present in the capital.[51]

According to Boardman, such foreign influence on India was important, just as many other Old World empires have been influenced by foreign cultures as well:

The visual experience of many Ashokan and later city dwellers in India was considerably conditioned by foreign arts, translated to an Indian environment, just as the archaic Greek had been by the Syrian, the Roman by the Greek, and the Persian by the arts of their whole empire.[56]

Sources

[edit]"The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity" John Boardman, Princeton University Press, 1993

"The Greeks in Asia" by John Boardman, Thames and Hudson, 2015 Online version[usurped]

See also

[edit]- Modern photographs of the Pataliputra capital: Views of the front: [30] (mirrored image), [31] Archived 4 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, [32] Archived 4 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, [33]. Views of the back: [34] Archived 23 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, [35] Archived 23 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine. See also Virtual Museum photographs

- Greco-Bactrian kingdom

- Mathura lion capital

References

[edit]- ^ "The Digital South Asia Library -". Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Report on the excavations at Pataliputra (Patna)" Calcutta, 1903, page 16 [1]

- ^ "Report on the excavations at Pataliputra (Patna)" Calcutta, 1903, pages 16, 17, 40 and 59 [2]

- ^ "A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture" by Deborah S. Hutton, John Wiley & Sons, 2015, p.438 [3]

- ^ "Report on the excavations at Pataliputra (Patna)" Calcutta, 1903, page 40 [4]

- ^ Presents were exchanged between Greek and Mauryan rulers. Classical sources have recorded that following their treaty, Chandragupta and Seleucus exchanged presents, such as when Chandragupta sent various aphrodisiacs to Seleucus: "And Theophrastus says that some contrivances are of wondrous efficacy in such matters as to make people more amorous. And Phylarchus confirms him, by reference to some of the presents which Sandrakottus, the king of the Indians, sent to Seleucus; which were to act like charms in producing a wonderful degree of affection, while some, on the contrary, were to banish love" Athenaeus of Naucratis, "The deipnosophists" Book I, chapter 32 Ath. Deip. I.32. Mentioned in McEvilley, p.367

- ^ Chandragupta's son Bindusara 'Amitraghata' (Slayer of Enemies) also is recorded in Classical sources as having exchanged present with Antiochus I and asked for a philosopher: "But dried figs were so very much sought after by all men (for really, as Aristophanes says, "There's really nothing nicer than dried figs"), that even Amitrochates, the king of the Indians, wrote to Antiochus, entreating him (it is Hegesander who tells this story) to buy and send him some sweet wine, and some dried figs, and a sophist; and that Antiochus wrote to him in answer, "The dry figs and the sweet wine we will send you; but it is not lawful for a sophist to be sold in Greece" Athenaeus, "Deipnosophistae" XIV.67 The Literature Collection: The deipnosophists, or, Banquet of the learned of Athenæus (volume III): Book XIV

- ^ Buddhist Landscapes in Central India, Julia Shaw, Left Coast Press, 2013, p.46 [5]

- ^ Students' Britannica India, Popular Prakashan, 2000, p.165

- ^ A History of India, Hermann Kulke, Dietmar Rothermund, Psychology Press, 2004, p.75 [6]

- ^ Views of the front: [7] (mirrored image), [8] Archived 4 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, [9] Archived 4 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, [10]. Views of the back: [11] Archived 23 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine, [12] Archived 23 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture by Deborah S. Hutton, John Wiley & Sons, 2015, p.438 [13]

- ^ a b "Buddhist Architecture" by Huu Phuoc Le Grafikol, 2010, p.44

- ^ a b the "pilaster capitals with Greek florals and a form which is of Greek origin (though generally described as Persian) go back to Late Archaic."in "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity" John Boardman, Princeton University Press, 1993, p.110

- ^ "Excavation Sites in Bihar - Archaeological Survey of India". Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d BOARDMAN, JOHN (1 January 1998). "Reflections on the Origins of Indian Stone Architecture". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 12: 13–22. JSTOR 24049089.

- ^ a b c "The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE-200 CE" Robin Coningham, Ruth Young Cambridge University Press, 31 aout 2015, p.414 [14]

- ^ "The architectural closeness of certain buildings in Achaemenid Iran and Mauryan India have raised much comment. The royal palace at Pataliputra is the most striking example and has been compared with the palaces at Susa, Ecbatana, and Persepolis" Aśoka and the decline of the Mauryas, Volume 5, p.129, Romila Thapar, Oxford University Press, 1961

- ^ "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity" John Boardman, Princeton University Press, 1993, p.110

- ^ Archaeologists James Fergusson and architect Richard Phené Spiers were the first to make the precise comparison with the capital type from Ionia in "History Of Indian And Eastern Architecture" Vol I, Note of page 207 [15]. Today, art historians such as John Boardman confirm the comparisons and similarities between these categories of artifacts.

- ^ "For architecture, Pataliputra offers a stone capital in the form of a Greek anta capital and with Greek decoration – flame-palmettes, rosettes, tongues and bead-and-reel. The same form appears elsewhere, better disguised." in "The Greeks in Asia" by John Boardman Thames and Hudson, 2015, Chapter 6 [16][usurped]

- ^ "These flat, splaying members with cavetto sides, have a long history in Greek architecture as anta capitals, and the rolls at upper and lower sides are also seen" John Boardman, "The Origins of Indian Stone Architecture", p.19 : "An interesting flat capital which, though differing from the classic forms, bears a distinct resemblance to the capitals of the pilasters of the Temple of Apollo Didymaeos at Miletos" [17]

- ^ "CHAPITEAU D'ANTE À VOLUTES LATÉRALES : il s'agit d'un chapiteau ionique, d'époque archaïque, caractérisé par le fait que sa face antérieure présente un kymation, ou une succession de moulurations, tandis que ses faces latérales présentent des volutes superposées. All. ANTENKAPITELL (n) MIT SEITLICHEN VOLUTEN (f. pi.); angl. ANTA CAPITAL WITH VOLUTE SIDES; it. C. D'A. CON VOLUTE LATERALI; gr.m. έπίκρανο (το) παρα-στάδας μέ πλευρικές έλικες. Ce chapiteau se caractérise aussi par le fait que sa face antérieure montre un profil globalement convexe ou droit, tandis que ses faces latérales sont nettement concaves, élargissant la pièce vers le haut." in "Dictionnaire méthodique de l'architecture grecque et romaine. II. Eléments constructifs : supports, couvertures, aménagements intérieurs" de René Ginouvès p.106 [18]

- ^ NEW FRAGMENTI'S OF THE PARTHENON ACROTERIA, The American School of Classical Studies at Athens [19]

- ^ The Sanctuary of Athena Nike in Athens: Architectural Stages and Chronology, Ira S. Mark, ASCSA, 1993, p.83 [20]

- ^ Rebecca Brown in A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture (2015), p.438 describes the Pataliputra capital as "a single quasi-Ionic pillar capital" [21]

- ^ Hutton, Deborah S. (22 June 2015). A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119019534. Retrieved 15 January 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d The East: Buddhists, Hindus and the Sons of Heaven, Architecture in context II, Routledge, 2015, by Christopher Tadgell p.24

- ^ File:Bharhut pillar capital.jpg

- ^ a b Waddell, Report on Excavations, pp 24 and 40

- ^ a b Fortified Cities of Ancient India: A Comparative Study, p.11 p.40-43 Dieter Schlingloff, Anthem Press, 2014 [22]

- ^ "The palissade defenses where in Bulandi Bagh" in Fortified Cities of Ancient India: A Comparative Study, p.11 p.40-43 Dieter Schlingloff, Anthem Press, 2014, p.42 [23]

- ^ The pillars "owe something to the pervasive influence of Achaemenid architecture and sculpture, with no little Greek architectural ornament and sculptural style as well. Notice the florals on the bull capital from Rampurva, and the style of the horse of the Sarnath capital, now the emblem of the Republic of India." "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity" by John Boardman, Princeton University Press, 1993, p.110

- ^ "Buddhist Architecture" by Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 2010, p.40

- ^ a b Archaeological Survey Of India Annual Report 1906-7. 1909. p. 72.

- ^ a b c Mani, B. R. (2012). Sarnath : Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Archaeological Survey of India. p. 60.

- ^ Majumdar, B. (1937). Guide to Sarnath. p. 41.

- ^ Presented as a "Mauryan capital, 250 BC" with the addition of recumbant lions at the base, in the page "Types of early capitals" in Brown, Percy (1959). Indian Architecture (Buddhist And Hindu). p. x.

- ^ Early Buddhist Narrative Art by Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky p.16

- ^ Early Byzantine Churches in Macedonia & Southern Serbia by R.F. Hoddinott p.17

- ^ a b India Archaeological Report, Cunningham, p185-196

- ^ Age of the Nandas and Mauryas by Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta Sastri p.376 sq

- ^ A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India (3 Vol. Set), Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd, 2003 p.87

- ^ "The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States"F. R. Allchin, George Erdosy, Cambridge University Press, 1995, listed in page xi [24]

- ^ "History Of Indian And Eastern Architecture Vol I". Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ File:Bharhut pillar capital.jpg

- ^ The East: Buddhists, Hindus and the Sons of Heaven, Architecture in context II, Routledge, 2015, by Christopher Tadgell p.24

- ^ The Arts of India, Southeast Asia, and the Himalayas at the Dallas Museum of Art, Published on 12 December 2013. Article with photograph [25]

- ^ 2500 Years of Buddhism by P.V. Bapat, p.283

- ^ a b "Hints that Ashoka replaced much of the wooden material of the Palace by stone" Asoka Mookerji Radhakumud, Motilal Banarsidass Publishing, 1995 p.96 [26]

- ^ a b c "Ashoka was known to be a great builder who may have even imported craftsmen from abroad to build royal monuments." Monuments, Power and Poverty in India: From Ashoka to the Raj, A. S. Bhalla, I.B.Tauris, 2015 p.18 [27]

- ^ a b Introduction to Indian Architecture Bindia Thapar, Tuttle Publishing, 2012, p.21 "Ashoka used the knowledge of stone craft to begin the tradition of stone architecture in India, dedicated to Buddhism."

- ^ Pliny the Elder, "The Natural History", 6, 21

- ^ Gardner's Art through the Ages: Non-Western Perspectives, Fred S. Kleiner, Cengage Learning, 2009, p14

- ^ Fa-Hien seeing the Ashoka Palace at Pataliputra thought "it was the work not of men but of spirits which piled up the stones, reared the walls and gates, and executed elegant carvings and in-laid sculptured works in a way which no human hand of this world could accomplish" quoted in Early history of Jammu region, Raj Kumar, Gyan Publishing House, 2010, p.383 [28]. Chinese original comment by Fa-Hien: "巴连弗邑是阿育王所治,城中王宫殿皆使鬼神作,累石起墙阙,雕文刻镂,非世所造" in 佛国记 (Records of the country of the Buddha) [29]

- ^ The origins of Indian Stone Architecture, John Boardman, p.21

![Temple 17 at Sanchi: a Gupta period tetrastyle prostyle temple with pillar capital arrangement of Classical appearance. 5th century CE[49]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1f/Sanchi_temple_17.jpg/120px-Sanchi_temple_17.jpg)