Paleobiota of the Burgess Shale

This is a list of the biota of the Burgess Shale, a Cambrian lagerstätte located in Yoho National Park in Canada.

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At 508 million years old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fossil beds containing soft-part imprints. During the Cambrian, the ecosystem of the Burgess Shale sat under 100 to 300 metres (330 to 1000 feet) of water at the base of a submarine canyon known as the Cathedral Escarpment, which today is a part of the Canadian Rockies. The ecosystem would have sat in dimly lit water, most likely at the edge, or in the Mesopelagic zone. The ecosystem was preserved by rapid mudslides that quickly buried organisms near, or on the seafloor, which helps explain the rarity of nektonic organisms at the site. The shale would’ve supported unique environments like brine pools that could’ve also helped to preserve the fossils. Notable areas that expose the Burgess Shale include the Walcott Quarry, Marble Canyon, Stephen Formation, Tulip beds, Stanley Glacier, the Trilobite Beds and the Cathedral Formation. With each site occupying a varying depth, and distance from the base of the escarpments.[1][2][3][4][5]

Arthropoda

[edit]Crown-group arthropods (euarthropods such as trilobites) and their stem-group relatives (such as radiodonts) are extremely diverse and some species are abundant in the Burgess Shale. Along with their earlier-diverging cousins, the "Lobopodians", they provide great information on early Panarthropod evolution.

| Arthropods | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Phylum | Higher taxon | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images |

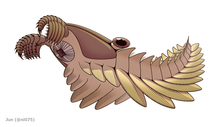

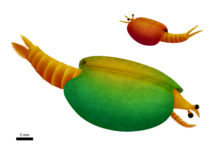

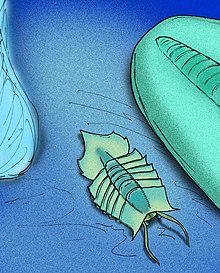

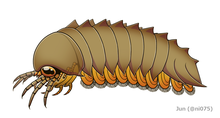

| Opabinia | Stem-group | Opabiniidae |

|

An opabiniid stem-group arthropod. This animal had five stalked eyes, a set of swimming trunk appendages, and a proboscis tipped with a claw-like appendage. |  |

| Anomalocaris | Stem-group | Radiodonta |

|

The largest radiodont from the Burgess shale, and the ecosystem’s apex predator. What it ate has been somewhat controversial due to the possible softness of its oral cone (mouthpart). |  |

| Hurdia | Stem-group | Radiodonta |

|

A hurdiid radiodont that possessed a large frontal head sclerite. This animal is known from deposits in North America. |  |

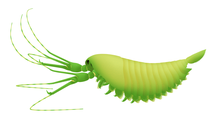

| Peytoia | Stem-group | Radiodonta |

|

A close relative of Hurdia that was originally named as a jellyfish, but was later recognized as the oral cone of the creature. This creature is also known from European deposits. |  |

| Stanleycaris | Stem-group | Radiodonta |

|

A basal hurdiid radiodont known from a variety of Cambrian deposits in North America. Although looking more like anomalocaridid and amplectobeluid radiodonts, it has features that more closely align it with the hurdiids. |  |

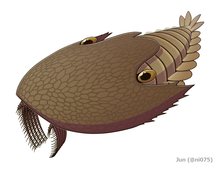

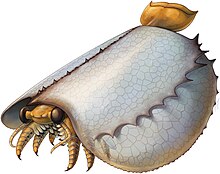

| Cambroraster | Stem-group | Radiodonta |

|

A unique looking hurdiid that bore a distinct horseshoe shaped head sclerite. This radiodont was first described in 2019, and was named after the fictional Millennium Falcon, which its dorsal carapace resembles. |  |

| Titanokorys | Stem-group | Radiodonta |

|

The largest hurdiid from the shale, and one of the largest Cambrian animals (up to a foot long). This radiodont was originally thought to have been a giant specimen of Cambroraster until late 2021. | |

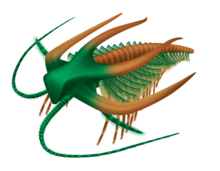

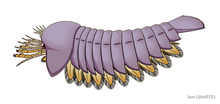

| Amplectobelua | Stem-group | Radiodonta |

|

Radiodont distinguished by its claw-shaped frontal appendages, another species A. symbrachiata, is known from China |  |

| Waptia | Arthropoda | Order |

|

A hymenocarine that possessed a shrimp-like body and is one of the earliest known examples of parental care in the fossil record. |  |

| Canadaspis | Arthropoda | Order |

|

A hymenocarine that is thought to have been benthic feeders that moved mainly by walking and possibly used its biramous appendages to stir mud in search of food. They have been placed within the Hymenocarina, which includes other bivalved Cambrian arthropods. |  |

| Fibulacaris | Arthropoda | Order |

|

A small, odarid hymenocarine that most likely swam in an inverted position in the water column. It most likely lived as a nektonic suspension feeder. |  |

| Balhuticaris | Arthropoda | Order |

|

A large hymenocarine arthropod that most likely lived a mainly nektonic lifestyle. This creature had about 110 pairs of biramous limbs, the most of any Cambrian aged arthropod. |  |

| Loricicaris | Arthropoda | Order |

|

A hymenocarine with an elongated, spined abdomen. It was found in the Kicking Horse Shale Member of the shale |  |

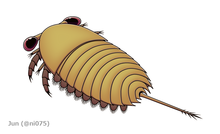

| Odaraia | Arthropoda | Order |

|

A hymenocarine arthropod that bore a large pair of eyes at the front of its body, and may have had two smaller eyes in between. It had a tubular body with at least 45 pairs of biramous limbs, and its tail had three fins – two horizontal, one vertical – which were used to stabilise the animal as it swam on its back. |  |

| Pakucaris | Arthropoda | Order |

|

A hymenocarine that ranged in length from 11.65 to 26.6 millimetres (0.459 to 1.047 in). The main bivalved carapace covers around 80% of the body, with the pygidium covering the remaining 20%. |  |

| Perspicaris | Arthropoda | Order |

|

Two named species are known from the Burgess Shale; Perspicaris dictynna and Perspicaris recondita, which differ in maximum size (66 millimetres (2.6 in) in P. recondita vs 29 millimetres (1.1 in) in P. dictynna), as well as proportions of the tail. |  |

| Nereocaris | Arthropoda | Order |

|

A large hymenocarine. This genus, including both species, is diagnosed by the presence of two lateral stalked eyes and one median eye, the possession of a laterally compressed bivalved carapace with hook-like elements, and a telson with a triangular medial process and a three-segmented elongate lateral process. |  |

| Tokummia | Hymenocarina |

|

A hymenocarine known from the Marble canyon deposits that was one of the first animals that evolved claws. The genus name Tokummia named after Tokumm Creek which runs through the Marble Canyon. The species name katalepsis means Greek word for "seizing", "gasping" or "holding". |  | |

| Branchiocaris | Hymenocarina |

|

A hymenocarine that had a pair of short segmented tapered antennules with at least 20 segments, as well as a pair of claw appendages. It was likely an active swimmer, and used the claw appendages to bring food to the mouth. |  | |

| Plenocaris | Hymenocarina |

|

This hymenocarine was originally described as a species of Yohoia by Walcott in 1912, but was placed into its own genus in 1974. |  | |

| Tuzoia | Arthropoda | Hymenocarina |

|

A genus of large hymenocarine known from Early to Middle Cambrian marine environments from what is now North America, Australia, China, Europe and Siberia. The large, domed carapace reached lengths of 180 millimetres (7.1 in), making them amongst the largest known Cambrian arthropods. |  |

| Hymenocaris | Arthropoda | Hymenocarididae | A Malacostracan arthropod that somewhat resembled a shrimp. |  | |

| Burgessia | Arthropoda | Unassigned |

|

Along with an uncertain placement in the arthropod family tree, Burgessia had a delicate structure below its round carapace. The largest individuals were only a little over four centimetres in length, and the smallest about half a centimetre from the front of the carapace to the tip of the rear spine. |  |

| Carnarvonia | Arthropoda | Unassigned |

|

An arthropod of uncertain placement. Only known from a single bivalved carapace that bears veins. |  |

| Worthenella | Arthropoda | Family Kootenichelidae |

|

An elongate arthropod of uncertain affinities, only known from a single specimen with 44 body segments with limbs. |  |

| Kootenichela | Arthropoda | Family Kootenichelidae |

|

Kootenichela has appendages bound to the trunk are poorly sclerotised. It was approximately 4 centimetres (1.6 in) long. Most prominent are the claw-like, spinose cephalic appendages, which seem to suggest affinities with Megacheira, the "great appendage" arthropods. However, study in 2015 researchers could not confirm neither the head configuration nor the megacheiran interpretation of the anatomy. Kootenichela has been subsequently suggested to be a chimera of various arthropods such as a bivalved arthropod. |

|

| Liangshanella | Arthropoda | Bradoriida |

|

A bradoriid arthropod. 6263 specimens of Liangshanella are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they are 11.9% of the community. |  |

| Marrella | Arthropoda | Marrellomorpha |

|

The most common organism of the Burgess Shale fauna. It was initially called the "Lace Crab" by Walcott, and was described more formally as an odd trilobite. In 1971, Whittington undertook a thorough redescription of the animal and, on the basis of its legs, gills and head appendages, concluded that it was neither a trilobite, nor a chelicerate, nor a crustacean. It carried a shield extending from its head over its gills. The brush-like appendages of its head probably swept food into its mouth. It is likely to have been an active swimmer with its swimming appendages used in a backstroke motion, with the large spines acting as stabilizers. |  |

| Skania | Arthropoda | Marrellomorpha? |

|

A somewhat enigmatic arthropod that has been speculated to have belonged to the Marrellomorpha. |  |

| Primicaris | Arthropoda | Marrellomorpha? |

|

An arthropod originally thought to have been a nektaspid, but is now considered a possible marrellomorph. |  |

| Emeraldella | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A vicissicaudatan arthropod that was aligned close to the trilobites. This creature had caudal flaps that are present on the terminal tergite, alongside an elongated spine. |  |

| Sidneyia | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

Sidneyia was a large 13 centimeter (5.1 in) long predator of the Burgess Shale, and ate trilobites and hyolithids. It was named after Walcott's second son, Sidney. |  |

| Tegopelte | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A species of large (up to 28 centimetres (11 in) long) soft-bodied arthropod known from two specimens from the Burgess Shale. Trackways that may have been produced by this organism or a close relative are known from the Kicking Horse Shale, stratigraphically below its body fossil occurrences. It is currently classified as a concilitergan arthropod within the Artiopoda. |  |

| Helmetia | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

Another concilitergan arthropod. Fossils are both rare and poorly known; the genus was described by Walcott in 1918 and has not been reexamined, though it was briefly reviewed in the 1990s and has been included in a number of cladistic analyses. It has been lumped with the arachnomorphs. One analysis has resolved the Helmetiiida as a robust clade and the closest relatives of trilobites. |  |

| Molaria | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

An artiopodan arthropod of uncertain affinity. The body of Molaria consisted of a head shield (cephalon), a trunk consisting of eight sections (tergites), and a telson, which included a short ventral spine and a long posterior spine. |  |

| Naraoia | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A nektaspid arthropod that belonged to the family Naraoiidae, that lived from the early Cambrian to the late Silurian period. The species are characterized by a large alimentary system and sideways oriented antennas. It reached small to average sizes (about 2-4.5 cm long). |  |

| Hanburia | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A trilobite possibly belonging to the family Dolichometopidae. |

|

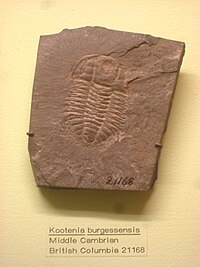

| Kootenia | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A trilobite belonging to the family Dorypygidae. Its major characteristics are that of the closely related Olenoides, including medium size, a large glabella, and a medium-sized pygidium, but also a lack of the strong interpleural furrows on the pygidium that Olenoides has. |

|

| Ogygopsis | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A trilobite belonging to the family Dorypygidae. It is the most common fossil in the Mt. Stephen fossil beds there, but rare in other Cambrian faunas. Its major characteristics are a prominent glabella with eye ridges, lack of pleural spines, a large spineless pygidium about as long as the thorax or cephalon. |  |

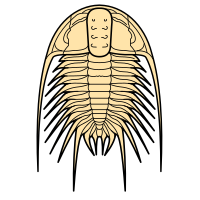

| Olenoides | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

Olenoides is an average size trilobite (up to 9 cm long), broadly oval in outline. Its cephalon is semi-circular. The glabella is parallel-sided, rounded at its front and almost reaches the anterior border. Narrow occular ridges curve backwards from the front of the glabella to the small, outwardly-bowed eyes. The librigenae narrow backward into straight, slender genal spines that reach as far as the third thorax segment. Thorax consists of seven segments that end in needle-like spines. |

|

| Oryctocephalus | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A trilobite belonging to the family Oryctocephalidae. This small- to medium-sized trilobite's major characteristics are prominent eye ridges, pleural spines, long genal spines, spines on the pygidium, and notably four furrows connecting pairs of pits on its glabella. Juvenile specimens have been found with only 5 or 6 thoracic segments and about one eighth of adult size, as well as about 2 mm wide. |

|

| Parkaspis | Arthropoda | (unranked) | A trilobite belonging to the family Zacanthoididae. | ||

| Zacanthoides | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A trilobite belonging to the family Zacanthoididae. It was a nektobenthic predatory carnivore. Its major characteristics are a slender exoskeleton with 9 thoracic segments, pleurae with long spines, additional spines on the axial rings, and a pygidium that is considerably smaller than its cephalon. | |

| Ptychagnostus | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

Several agnostid artiopods (usually considered trilobites). |

|

| Peronopsis | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

| |

| Pagetia | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

| |

| Chancia | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A trilobite belonging to the family Alokistocaridae. Chancia was a particle feeder. Its major characteristics are a normal glabella but an enlarged cephalon due to a pre-glabellar field in front of the glabella, as well as developed eye ridges, medium-sized genal spines, and an extremely small pygidium. | |

| Ehmaniella | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A trilobite. Ehmaniellas major characteristics are a wide cranidium, heavy eye ridges, longitudinal striae on the pre-glabellar area, and a small pygidium with few segments. | |

| Elrathia | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A genus of trilobite belonging to Ptychopariacea. E. kingii is one of the most common trilobite fossils in the USA. It is locally found in extremely high concentrations within the Wheeler Formation in the U.S. state of Utah. E. kingii has been considered the most recognizable trilobite. Commercial quarries extract E. kingii in prolific numbers, with just one commercial collector estimating 1.5 million specimens extracted in a 20-year career. |

|

| Elrathina | Arthropoda | (unranked) |

|

A genus of trilobite belonging to Ptychopariacea. | |

| Spencella | Arthropoda | (unranked) | A trilobite belonging to the family Ptychopariidae. | ||

| Habelia | Arthropoda | Chelicerata |

|

While previously enigmatic, a 2017 redescription found that Habelia formed a clade (Habeliida) with Sanctacaris, Utahcaris, Wisangocaris and Messorocaris as a stem-group to Chelicerata. Habelia is thought to have been durophagous, feeding on hard shelled organisms. |  |

| Sanctacaris | Arthropoda | Chelicerata |

|

A member of the clade Habeliida, related to chelicerates. Sanctacaris was only first described in 1981. It possessed a large flat tail, suggesting it was a good swimmer, a group of six appendages in each side of its body, and a very streamlined head. |  |

| Mollisonia | Arthropoda | Chelicerata |

|

An extinct genus of Cambrian arthropod. An observation published in 2019 suggests this genus is a basal chelicerate, closer to crown group Chelicerata than members of Habeliida. |  |

| Thelxiope | Arthropoda | stem-groupChelicerate |

|

A relative of Mollisonia that possessed a long spine that protruded out of its posterior. |  |

| Leanchoilia | Arthropoda | Megacheira |

|

A megacheiran arthropod. Leanchoilia is distinguished from other arthropods by its arms. They split into three appendages, probably to find food, as they lack the spiny characteristic of predators. |  |

| Yohoia | Arthropoda | Megacheira |

|

Yohoia was a streamlined megacheiran that had around 20 segments. It has been compared to modern mantis shrimp, where It had two four-fingered hands, and may have preyed on trilobites, smashing or spearing them with its fingers. |  |

| Actaeus | Arthropoda | Megacheira |

|

A megacheiran arthropod containing the single species Actaeus armatus. It is known from a single specimen recovered from the Burgess Shale, and it may be poorly preserved specimen of Alalcomenaeus.[6] The specimen is over 6 cm long and has a body consisting of a head shield, 11 body tergites, and a terminal plate. |  |

| Alalcomenaeus | Arthropoda | Megacheira |

|

One of the most widespread and longest-surviving arthropod genera of the Early and Middle Cambrian. Its large eyes and the long flagella on its great appendages, combined with its large feeding apparatus and the spines on its inner limb branches, are more consistent with a predatory lifestyle, and the most recent interpretation has it feeding on organisms that lived on or in the surface of the sea floor. |  |

| Yawunik | Arthropoda | Megacheira |

|

Yawunik is named after a primordial sea monster in Ktunaxa mythology. Compared to Leanchoilia it bore teeth on great appendages, suggesting an enhanced ability to grasp prey. |  |

| Isoxys | Arthropoda | Family

Isoxyidae |

|

A basal bivalved arthropod, member of the family Isoxyidae. It had a pair of large spherical eyes (which are the most commonly preserved feature of the soft-bodied anatomy), and two large appendages It is possible that these appendages are homologous to the great appendages of radiodonts and megacheirans. |  |

| Surusicaris | Arthropoda | Family

Isoxyidae |

|

A close relative of Isoxys from the Burgess shale. The only known specimen (ROM 62976), has a roughly semicircular bivalved carapace, which is approximately 1.49 centimetres (0.59 in) long and 0.89 centimetres (0.35 in) tall. The head has a pair of rounded eyes, and a pair of upward-curling segmented frontal appendages with at least five segments, the second, third and fourth of which bear a spine, with three long spines and at least one short spine on the fifth and terminal segment. It alongside Isoxys are considered basal stem-group arthropods. |  |

| Sarotrocercus | Arthropoda | Not applicable |

|

An arthropod of uncertain affinities. In the original description, Sarotrocercus had been interpreted as a pelagic, nektonic animal that swam freely on its back, moving perhaps through movements of the trunk appendages and the action of its long tail tuft. However, based on the redescription by Haug et al. 2011, Sarotrocercus may had been benthic or at least swimming close to the seafloor, as the robust head appendages rather suggest a grasping or raking function. |  |

| Caryosyntrips | Stem-group | Not applicable |

|

An enigmatic panarthropod that was characterized by their forward facing grasping appendages. Originally classified as a problematic radiodont. Its name literally translates to "nutcracker". |

|

Lobopodians

[edit]Lobopodians, a grouping of worm-like panarthropods from which arthropods arose, were present in the shale.

| Lobopodians | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Higher Taxa | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images | |

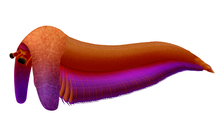

| Hallucigenia | Hallucigeniidae |

|

A spined lobopodian. This creature is one of the more iconic taxa from the shale. The generic name reflects the type species' unusual appearance and eccentric history of study; when it was erected as a genus, H. sparsa was reconstructed as an enigmatic animal upside down and back to front. Hallucigenia was later recognized as a lobopodian, a grade of Paleozoic panarthropods from which the velvet worms, water bears, and arthropods arose. |  | |

| Entothyreos | Luolishaniidae |

|

A unique spined Lobopodian mainly known from the tulip beds site of the shale. This recently described panarthropod was a suspension feeder like most of the other members of its family. It is unique for possessing a large amount of sclerotization compared to other lobopodians, comparable to that of true arthropods. |  | |

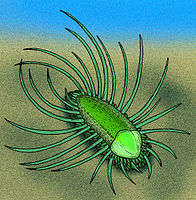

| Aysheaia | Protonychophora |

|

Aysheaia has ten body segments, each of which has a pair of spiked, annulate legs. The animal is segmented, and looks somewhat like a bloated caterpillar with a few spines added on — including six finger-like projections around the mouth and two grasping legs on the "head". Each leg has a subterminal row of about six curved claws. No jaw apparatus is evident. A pair of legs marks the posterior end of the body, unlike in onychophorans where the anus projects posteriad; this may be an adaptation to the terrestrial habit. |  | |

| Ovatiovermis | Luolishaniidae |

|

A suspension-feeding lobopodian. Ovatiovermis had nine pairs of lobopods. The first two pairs were elongate and had approximately 20 pairs of spines on each lobopod, with a bifid claw at each tip. The third to sixth pairs of lobopods were shorter and their paired spines were much smaller. On these four pairs of lobopods the spines were only large near the tip. The last three pairs of lobopods did not have the paired spines, showing that these spines were used for filter-feeding. | ||

| Collinsovermis | Luolishaniidae |

|

A heavily armored luolishaniid Lobopodian, and was probably a suspension feeder. It was originally nicknamed the "Collins Monster". It was a tiny worm-like soft bodied animal measuring about 3 cm long with multiple pairs of legs called lobopods. It bears 14 pairs of lobopods, which are closely attached to the main body unlike in other lobopodians. The anterior six pairs are unusual in that they are much longer than the posterior pairs or typical lobopod. |  | |

Sponges

[edit]Sponges (Porifera) were extremely diverse in the shale, with many of them belonging to the class Demospongiae.[1][7]

| Porifera | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images | |

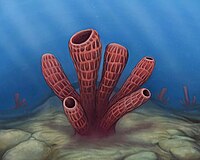

| Capsospongia | Demospongiae |

|

A middle Cambrian sponge genus known from 3 specimens in the Burgess shale. It has a narrow base, and consists of bulging rings which get wider further up the sponge, resulting in a conical shape. Its open top was presumably used to expel water that had passed through the sponge cells and been filtered for nutrients. |

| |

| Choia | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of demosponge ranging from the Cambrian until the Lower Ordovician periods. Fossils of Choia have been found in the Burgess Shale in British Columbia; the Maotianshan shales of China; the Wheeler Shale in Utah; and the Lower Ordovician Fezouata formation. It was first described in 1920 by Charles Doolittle Walcott. |

| |

| Crumillospongia | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of middle Cambrian sponges known from the Burgess Shale and other localities from the Lower and Middle Cambrian. Its name is derived from the Latin crumilla ("money purse") and spongia ("sponge"), a reflection of its similarity to a small leathery money purse. | ||

| Diagoniella | Hexactinellida |

|

A genus of sponge known from the Burgess Shale. This sponge formed a conical shape, with a diagonally arranged skeleton. |

| |

| Eiffelia | Stem-group Hexactinellida |

|

A genus of sponges known from the Burgess Shale as well as several Early Cambrian small shelly fossil deposits. It is named after Eiffel Peak, which was itself named after the Eiffel Tower. It was first described in 1920 by Charles Doolittle Walcott. It belongs in the Hexactinellid stem group. Eiffelia generally have star-shaped six-rayed spicules, with rays diverging at 60°, occasionally with a seventh ray perpendicular to the other six. |

| |

| Eiffelospongia | Stem-group Hexactinellida |

|

A genus of sponge known from the Mount Stephen Trilobite Beds. It had a small ovoid shape, with a hairy-like root tuft. | ||

| Falospongia | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of sponge made up of radiating fronds, known from the Burgess Shale. Irived from the Latin fala ("scaffold") and spongia ("sponge"), referring to the open framework of the skeleton. It superficially resembles Haplistion but is monaxial. |

| |

| Fieldospongia | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of demosponge. Described in 1920 as Tuponia bellilineata by Walcott in his monograph on sponges from the Burgess Shale. The only known specimen purportedly came from the Mount Whyte Formation. | ||

| Halichondrites | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of sea sponge. It had an elongated, cone-like structure, with long spicules. |

| |

| Hamptonia | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of sea sponge. It is known from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale and the Lower Ordovician Fezouata formation. It was first described in 1920 by Charles Walcott. | ||

| Hamptoniella | Demospongiae |

|

A three dimensional sponge that was filled with many canals. | ||

| Hazelia | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of spicular demosponge known from the Burgess Shale, the Marjum formation of Utah, and possibly Chengjiang. It was described by Charles Walcott in 1920. Its tracts are mainly radial and anastomose to form an irregular skeleton. Its oxeas form a fine net in the skin of the sponge. It is one of the more common sponges of the shale. |

| |

| Leptomitella | Demospongiae | A genus of demosponge. | |||

| Leptomitus | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of demosponge known from the Burgess Shale. Its name is derived from the Greek lept ("slender") and mitos ("thread"), referring to the overall shape of the sponge. | ||

| Petaloptyon | Hexactinellida |

|

A goblet-shaped hexactinellid sponge known from rare fragments from the Burgess Shale. The fragments show the living animal had a stalk, and had panels with a lattice pattern. |

| |

| Pirania | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of cactus-like sea sponge known from the Burgess Shale and the Fezouata formation. It is named after Mount St. Piran, a mountain situated in the Bow River Valley in Banff National Park, Alberta. It was first described in 1920 by Charles Walcott. |

| |

| Protoprisma | Demospongiae |

|

This creature was a glass sponge that had long, prismatic branches. | ||

| Protospongia | Hexactinellida |

|

A genus of hexactinellid sponge. Many other sponges from Ordovician and Devonian deposits are placed in this genus due to the architecture of their spicules resembling that of Protospongia. | ||

| Stephenospongia | Hexactinellida |

|

A genus of sponge known from a single specimen in the Trilobite beds of the Burgess Shale. Its body had numerous conspicuous holes. | ||

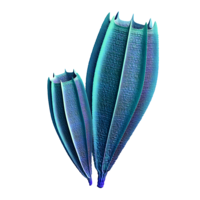

| Takakkawia | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of sponge in the order Protomonaxonida and the family Takakkawiidae. It reached around 4 cm in height, and its structure consisted of four columns of multi-rayed, organic spicules (perhaps originally calcareous or siliceous) that align to form flanges. The spicules form blade-like structures, ornamented with concentric rings. It was named after Takakkaw Falls, which marks the start of the trail to Fossil Ridge. |

| |

| Ulospongiella | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of sponge known only from the Burgess Shale deposit. It contains only one species, Ulospongiella ancyla. The generic name is derived from the Greek words oulus ("wooly" or "curly") and spongia ("sponge"), referring to the curled or curved spicules forming the skeleton. The specific name, ancyla, is from the Greek ankylos ("bent" or "hooked"), also referring to the curved spicules. | ||

| Vauxia | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of demosponge that had a distinctive branching mode of growth. Vauxia had a skeleton of spongin (flexible organic material) common to modern day sponges. Much like Choia and other sponges, Vauxia fed by extracting nutrients from the water. Vauxia is named after Mount Vaux, a mountain in Yoho National Park. |

| |

| Wapkia | Demospongiae |

|

A genus of sea sponge with radial sclerites, known from the Burgess Shale. It was first described in 1920 by Charles Walcott. | ||

Comb-jellies (Ctenophora)

[edit]Ctenophores, also known as comb jellies, are rare in the shale, but three genera are known from the site.[8][9]

| Ctenophora | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images | |

| Ctenorhabdotus |

|

This ctenophore had rows of cilia to help it swim in the water column. It had around 24 comb rows on its body, around three times as more than extant comb jellies. |

| |

| Fasciculus |

|

This stem-group ctenophore lived around 515 to 505 million years ago. It had two rows of long and short comb rows, a feature not seen in the fossil record or among modern species. |

| |

| Xanioascus |

|

This ctenophore had 24 comb rows - in contrast to all modern forms which have only 8, and was described in 1996 by Simon Conway Morris. |

| |

Hemichordata

[edit]Many of the Hemichordates from the shale have either remained enigmatic, or were once classified under other groupings.[10][11]

| Hemichordata | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images | |

| Chaunograptus | Graptolithina? |

|

This enigmatic hemichordate has been interpreted as a possible graptolite. | ||

| Gyaltsenglossus | A basal hemichordate, sharing characters of both pterobranchs and enteropneusts | ||||

| Oesia | incertae sedis |

|

This common, enigmatic worm-like organism has been interpreted as either a chaetognath, or some kind of hemichordate. Some fossils have been found in Margaretia, which is a mysterious fossil that has been found to possibly represent some kind of organic tube that this hemichordate used as a nest. |

| |

| Yuknessia | Pterobranchia |

|

This colonial pterobranch (a grouping of filter feeding hemichordates that live in tubes on the ocean floor) was originally interpreted as a green algae. | ||

| Dalyia | Pterobranchia? |

|

A possible pterobranch. | ||

| Spartobranchus | Enteropneusta |

|

An acorn worm. It is similar to the modern representatives of the family Harrimaniidae, distinguished by branching fiber tubes. It is a believed predecessor of Pterobranchia, but this species is intermediate between these two classes. Studies show that these tubes were lost in the line leading to modern acorn worm, but remained in the graptolites. | ||

Annelida

[edit]A number of different Annelid worms are known from the shale.[12][13]

| Annelids | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Phylum | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images | |

| Burgessochaeta | Annelida | Polychaeta |

|

A bristle worm that used tentacles to feel for food. It had 24 segments, each carrying a pair of appendages used for propulsion. is thought to have been a decomposer or scavenger on organic material. Specimens have been found from both continental slope and deep-water environments, indicating that this was a widespread animal. |  | |

| Canadia | Annelida | Polychaeta |

|

A genus of annelid worm. The animal's most notable feature is the many notosetae (rigid setae extending from dorsal branches of notopodia) along the back of the animal that are characteristic of polychaete worms. It would have had the ability to creep along the seafloor using the ventral counterpart of the notopodia, which are termed neuropodia. |

| |

| Insolicorypha | Annelida | Polychaeta |

|

a genus of polychaetes known from the Burgess Shale. A single specimen of Insolicorypha is known from the Greater Phyllopod bed. This creature is the rarest polychaete from the shale. |

| |

| Peronochaeta | Annelida | Polychaeta |

|

a genus of annelid. 19 specimens of Peronochaeta are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they constitute < 0.1% of the community. | ||

| Stephenoscolex | Annelida | Polychaeta |

|

A slender bristle worm that was covered in a large number of tiny bristles. Stephenoscolex contributes 0.29% of the total faunal community. | ||

| Kootenayscolex | Annelida | non-applicable |

|

An annelid worm. It appears to have been an aquatic worm with about 56 bristles on each of up to 25 segments, serving to propel it through mud or water. |

| |

| Ursactis | Annelida | non-applicable |

|

An polychaete worm. It is a small species, roughly 3–15 millimetres (0.1–0.6 in) long, and possesses a pair of large palps. It has between 8 and 10 segments, a smaller number than other most polychaetes. |  | |

Priapulida

[edit]Various stem-group priapulids are known from the Burgess Shale.

| Priapulids | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Phylum | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images |

| Ancalagon | Priapulida (?) | Archaeopriapulida |

|

An extinct priapulid worm. This worm averaged around 6 centimeters in length. Its proboscis was armed with circum-oral hooks at the anterior. There were about 10 of these hooks, with all of them being equal in size. |

|

| Fieldia | Priapulida (?) | Archaeopriapulida |

|

This priapulid was originally interpreted as an arthropod; its trunk bears a dense covering of spines. It most likely fed on sea-floor mud, evidenced by the frequent presence of sediments preserved in its gut. | |

| Louisella | Priapulida (?) | Archaeopriapulida |

|

A genus of priapulid worm. It was originally described by Charles Walcott in 1911 as a holothurian echinoderm. It's also been interpreted as an annelid and a sipunculan, (neither on particularly compelling grounds) and a priapulid. |

|

| Ottoia | Priapulida (?) | Archaeopriapulida |

|

This priapulid is the most common worm of the Burgess shale. Ottoia was a burrower that hunted prey with its eversible proboscis. It also appears to have scavenged on dead organisms. |

|

| Scolecofurca | Priapulida (?) | Stem-group |

|

The only known species in the genus, Scolecofurca rara was first described by Conway Morris in 1977 as a possible primitive priapulid, but later shown to belong to the priapulid stem group. Scolecofurca's single fossil specimen is 6.5 centimeters in length. The fossil displays a proboscis, which bore two 3 millimeter-long tentacles at the anterior. The tentacles most likely would have functioned for sensory purposes rather than for feeding. | |

| Selkirkia | Priapulida (?) | Archaeopriapulida |

|

A genus of predatory, tubicolous priapulid worm. Many burrows of this worm have been found in the shale, but many of them (up to 80%) have been found empty without the worms in them. |

|

Mollusca

[edit]The molluscs of the Burgess shale are diverse in body shapes, the ecological niches they filled, and their enigmatic qualities.[14]

| Mollusca | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Phylum | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images | |

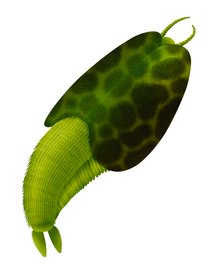

| Odontogriphus | Mollusca (?) |

|

A bilaterian animal that had a flat, oval shaped body. This creature possessed a rasping tongue covered in multiple rows of teeth. Due to this feature resembling a radula, this creature is thought to represent a basal mollusk. |

| ||

| Oikozetetes | Animalia | incertae sedis |

|

An enigmatic shelled fossil that is possibly thought to represent a halkieriid, which have been considered early mollusks. | ||

| Orthrozanclus | Mollusca | Halkieriidae |

|

A two centimeter sized mollusk that was covered in a wide array of spines. This creature's name means "Dawn scythe". While this animal's placement is somewhat controversial, it has been aligned with the halkieriids, possibly linking them to Wiwaxia. |

| |

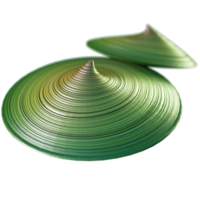

| Scenella | Mollusca | Superfamily |

|

A disk shaped mollusk that is somewhat enigmatic, and has been placed in a number of different groups (Gastropoda, Helcionelloida, or Monoplacophora). This mollusk is common in the shale, where they are often found in dense clusters. |

| |

| Wiwaxia | Mollusca? |

|

This animal possessed a set of carbonaceous scales and spines that protected it from predators. It resembled Orthrozanclus in appearance, but its placement in mollusca is still debated. |

| ||

Brachiopods

[edit]Many of the brachiopods from the site are members of the class Lingulata.[12][15]

| Brachiopoda | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images | |

| Acanthotretella | Lingulata |

|

Acanthotretella was a brachiopod of the class Lingulata. Most of the specimens of the genus were found within Walcott quarry, but it is one of the more rare brachiopods found in the site with it accounting for only 0.05% of the entire fauna. It reached a maximum size of around 8 mm in length. Like most brachiopods, it was a suspension feeder, but uniquely it attached itself to the seabed with a long pedicle. | ||

| Acrothyra | Lingulata |

|

A species of gregarious brachiopod. It was originally described by Walcott in 1924. It had a short pedicle, and most likely lived in groups with one another and fliter fed with their lophophores. | ||

| Diraphora | Rhynchonellata |

|

An early rhynchonellatid brachiopod that had rigid appearance to its shell. | ||

| Dictyonina | Paterinata |

|

A brachiopod belonging to the extinct order Paterinida. | ||

| Lingulella | Lingulata |

|

A genus of phosphatic-shelled brachiopod. It is known from the Burgess Shale to the Upper Ordovician Bromide Formation in North America. Some specimens of the brachiopod preserve the pedicle intact, which is normally rare in the fossil record. This brachiopod is thought to have been a generalist, as it appears consistently common throughout the strata of the Burgess Shale. |

| |

| Linnarssonia | Lingulata | A brachiopod belonging to the family Acrotretidae. | |||

| Micromitra | Paterinata |

|

This genus is the most ornamented of the Burgess Shale brachiopods. This creature reached a size of around 10 mm in length. Many specimens of Micromitra have been found attached to the sponge Pirania, suggesting an epibenthic lifestyle for this brachiopod. This creature had a large amount of bristles (setae) that extended far beyond the rim of the shell. |

| |

| Nisusia | Kutorginata |

|

An early rhynchonelliform brachiopod. Nisusias pedicle emerged from between its valves, as displayed by silicified material of N. sulcate, though it still has an opening at the apex of the pedicle valve. | ||

| Paterina | Paterinata |

|

A brachiopod that shows prominent growth lines on its fossils. They are very rare in the Phyllopod bed, with it only making up 0.03% of the community. | ||

Cnidaria

[edit]A wide variety of cnidarians like scyphozoans and conulariids are known from this site.[16][8]

| Cnidaria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images | |

| Byronia | Scyphozoa?(Order Byroniida) |

|

Byronia is thought to represent the polyp stage of a scyphozoan cnidarian that built narrow, chitinous tubes (theca) that were attached to the substrate by a disc. How this animal fed is unknown, but compared to other coexisting genera like Cambrorhytium, it is thought to have been a carnivore or a suspension feeder. It is thought to be closely related to coronatid scyphozoans. It was first described back in 1899. | ||

| Cambrorhytium | Staurozoa |

|

An enigmatic animal that was first described in 1908, and has been classified under a number of different groups. Currently it is thought to possibly represent a staurozoan cnidarian, more specifically a conulariid. It has also been interpreted as a cnidarian polyp of some description. The other possible affinity is with the hyolithid lophophorates. | ||

| Mackenzia | Actiniaria |

|

An elongated bag-like animal. It has been found attached directly to hard surfaces, such as brachiopod shells. Mackenzia is thought to be a cnidarian and appears most similar to modern sea anemones. Mackenzia was originally described by Charles Walcott in 1911 as a holothurian echinoderm. | ||

| Burgessomedusa | Medusozoa |

|

A free swimming medusa, likely either a stem group to Cubozoa or Acraspeda (the clade containing Staurozoa, Cubozoa and Scyphozoa).[17] |

| |

| Sphenothallus sp. | Staurozoa |

|

A problematic genus lately attributed to the holdfasts of conulariids. It was very widespread in paleozoic environments, and has been found attached to other fossils. Sphenothallus is represented in the Mount Stephen trilobite beds (which are a part of the Burgess Shale), where it co-occurs with the coexisting organisms Cambrorhythium and Byronia. |

| |

| Tubulella | stem-group |

|

A stem-group cnidarian that lived in a slender, conical tube. This creature was most likely related to scyphozoans. | ||

Echinodermata

[edit]The echinoderms of the shale represent extinct groups distantly related to extant groups.[8]

| Echinodermata | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | ||

| Gogia | Eocrinoidea |

|

This echinoderm was a primitive member of the eocrinoid group (which despite the name weren't closely related to crinoids). This creature had a plated body that formed a "bowling pin" shape. |

| |

| Lyracystis | Eocrinoidea |

|

This echinoderm was another eocrinoid, and a close relative of Gogia. This creatures arms formed a shape similar to a lyre. | ||

| Walcottidiscus | Edrioasteroidea |

|

This echinoderm is one of the earliest confirmed members of the edrioasteroidea, a grouping of pentagonally shaped echinoderms. | ||

Chordata

[edit]Chordates are very rare in the shale, but the two that are known are possibly being very important in the study of these creatures earlier evolution.[18]

| Chordata | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images |

| Metaspriggina |

|

A genus of animal that is considered to represent a primitive chordate, possibly transitional between cephalochordates and the earliest vertebrates, albeit this has been questioned because it seems to possess most of the characteristics attributed to craniates. It lacked fins and it had a weakly developed cranium, but it did possess two well-developed upward-facing eyes with nostrils behind them. |

|

| Pikaia |

|

A basal chordate described in 1911 by Walcott as an annelid worm, and in 1979 by Harry B. Whittington and Simon Conway Morris as a chordate. It became the "most famous early chordate fossil." Probably descended from an even earlier chordate based on fossil material from China, Pikaia swam through the Cambrian oceans like a modern fish. Originally thought to be the most primitive chordate, it had two lobe-like appendages on its head unlike vertebrates. | |

Gnathifera

[edit]| Gnathifera | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Phylum | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images |

| Capinatator | Chaetognatha |

|

An arrow worm from the Burgess Shale. It has the distinction of having 50 spines around its mouth. As with modern arrow worms, the spines were used to grasp prey for consumption. C. praetermissus is thought to represent a stage of chaetognathan evolution before arrow worms became planktonic swimmers. |

|

| Amiskwia | Total group |

|

A large, soft bodied animal. Recently it has been interpreted as a gnathiferan, which are generally small spiralians characterized by complex jaws made of chitin. |

|

Chancellorids

[edit]An extinct group of enigmatic sponge-like animals covered in hollow spines

| Incertae sedis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Phylum | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images | |

| Chancelloria | non-applicable | Chancelloriidae | Many of the areas of the shale | Superficially, this animal resembles a sea sponge, covered in spine-like sclerites. However it is a member of the extinct group Chancelloriidae, whose relationship to other animals are unclear. |

| |

| Archiasterella | non-applicable | Chancelloriidae | Many of the areas of the shale | A genus of chancellorid known from the Burgess Shale and earlier deposits, and originally described as Chancelloria by Walcott. The species may represent form taxa rather than true species. | ||

| Allonnia | non-applicable | Chancelloriidae | Many of the areas of the shale | A genus of chancelloriid. |  | |

Cyanobacteria

[edit]Cyanobacteria are photosynthesizers, and would have been important in the shale.[19][20]

| Cyanobacteria | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Phylum | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images | |

| Marpolia | Nostocales | non-applicable |

|

This genus has been interpreted as a cyanobacterium, but also resembles the modern cladophoran green algae. It is known from the Middle Cambrian Burgess shale and Early Cambrian deposits from the Czech Republic. It consists of a dense mass of entangled, twisted filaments. It may have been free-floating or grown on other objects, although there is no evidence of attachment structures. |

| |

| Morania | Cyanobacteria | Cyanophyceae |

|

A genus of cyanobacterium preserved as carbonaceous films. it is present throughout the shale, with thousands of specimens being known. It formed filamentous sheets, and resembles the modern cyanobacterium Nostoc. It would have had a role in binding the sediment together, and would have been a food source for such organisms as Odontogriphus and Wiwaxia. |

| |

Red algae (Rhodophyta)

[edit]Red algae are found in the shale, with three genera being known.[21][8]

| Rhodophyta | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images | |

| Bosworthia | Non applicable |

|

A genus of branching photosynthetic alga. 20 specimens of Bosworthia are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they constitute 0.04% of the community. One of its two original species has since been reassigned to Walcottophycus. | ||

| Dictyophycus | Non applicable |

|

A putative red algae. It formed leaf-like lobes that measured around 25mm across. Only the sturdier parts of the skeleton are known. | ||

| Wahpia | Rhodophyceae |

|

This small alga had an array of small, slender branches. It constitutes around 0.06% of the Phyllopod Bed community. | ||

| Waputikia | Rhodophyceae |

|

a possible red alga from the Burgess shale. It consists of a main stem about 1 cm across, with the longest recovered fossil 6 cm in length. Branches of a similar diameter emerge from the side of the main branch, then rapidly bifurcate to much finer widths. This genus is the rarest rhodophyte from the shale. | ||

Incertae sedis and miscellaneous

[edit]This section documents organisms from the shale whose taxonomic affinities are not fully understood,[22][23] or who do not fit into any of the above groups.

| Incertae sedis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Phylum | Class | Locality of Origin | Notes | Images |

| Banffia | Vetulicolia | Heteromorphida |

|

This bizarre deuterostome animal was a member of the Vetulicolia, whose placement in the tree of life has remained controversial. However, due to certain characteristics e.g. lacking gill slits, it may not be a vetulicolian, instead being placed closer to Protostomia. |

|

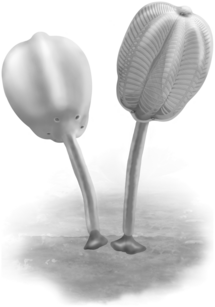

| Dinomischus | Animalia | non-applicable |

|

This cup shaped creature has been in the center of debate since its description in 1977. It sat on the ocean floor with a long stalk, and a small holdfast and was a filter feeder. Recent studies have suggested that it is likely stem-group ctenophoran.[24] |

|

| Echmatocrinus | Animalia | non-applicable |

|

This animal resembles a crinoid or an octocoral in appearance. It had a crown of seven-nine tentacles. This organism lived a solitary lifestyle, although juveniles are sometimes attached to (or budding from) adults. |

|

| Eldonia | Deuterostoma | Unranked |

|

A soft bodied, disk shaped animal. Currently it is thought to have been a cambroernid, which is a group of basal ambulacrarians. |

|

| Herpetogaster | Deuterostoma | Unranked |

|

A genus of cambroernid animal. It is most likely to have fed by snaring either small prey or edible particles in the tentacles and bringing the tentacles to the mouth. This animal secured itself to hard surfaces by using an extensible stolon that emerged from the body at about the ninth segment and secured the animal. It is often found secured to the sponge Vauxia. |

|

| Nectocaris | Lophotrochozoa (?) | Family |

|

A squid like-predator that is rare in the shale. Has been controversially suggested to be a cephalopod, but this is rejected by most scholars. This animal had a kite shaped body, and a single pair of tentacles. It was originally considered some kind of arthropod hence its name meaning (Swimming shrimp). |

|

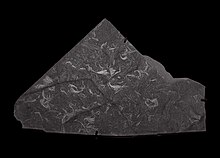

| Pollingeria | Animalia | non-applicable |

|

This problematic genus is worm-like in appearance, and is long and thin. Originally it was thought that these fossils represented the chaetae of polychaete worms. More recently, it has been assumed that each individual "chip" represents an entire organism.

In the photo, Panels 7, 8 and 9 depict Pollingeria. |

|

| Portalia | Animalia | non-applicable |

|

This creature is one of the many Burgess shale organisms that Walcott interpreted as a sea cucumber. More recently it has been suggested to have been a sponge. |  |

| Scathascolex | Animalia | Palaeoscolecida | A priapulid-like palaeoscolecid worm |  | |

| Priscansermarinus | Animalia | non-applicable |

|

This enigmatic creature was first interpreted as a lepadomorph barnacle. This would push back the origins of this crustacean group by another 200 or so million years. Recently its status as a barnacle, or even an arthropod in general has been questioned. |

|

| Siphusauctum | Animalia | non-applicable |

|

An enigmatic filter feeding animal, often nicknamed the "Tulip animal" due to its flower-like appearance. It lived by attaching itself to the substrate by a holdfast, it had a tulip-shaped body, called a calyx, into which it actively pumped water that entered through pores and filtered out and digested organic contents. It grew to a length of only about 20 cm (7.9 in). Recent studies have suggested it to be a stem-group ctenophore. |

|

| Haplophrentis | Lophotrochozoa | Hyolithia |

|

Haplophrentis was a hyolith, a grouping of strange, conical shelled invertebrates that lived throughout the Paleozoic. This animal was a filter feeder, using its lophophore to extract organic matter from passing seawater. The soft bodied fossils of this genus were important in establishing hyoliths as possible members of the lophophorata alongside brachiopods and bryozoans. |  |

| Fuxianospira | A filamentous fossil considered either to represent an alga or a coprolite. | ||||

| Tontoia | Unknown | Unknown | Initially suggested to represent an external mould of an arthropod exoskeleton, but it currently considered a nomen dubium, and it is unclear as to whether it is even an arthropod at all. |  | |

| Thaumaptilon | Unknown | Unknown |

|

Thaumaptilon is a genus of feather shaped animal from the shale which some authors have compared to members of the Ediacaran biota, which went extinct long before the Burgess shale was deposited. More specifically, it has been compared to the Ediacaran organism Charnia. It got up to 20 cm long, and attached itself to the sea floor with a holdfast. One side of its surface was covered in spots, which might have been zooids. |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Paleontology |

|---|

|

|

Paleontology Portal Category |

References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Burgess Shale". burgess-shale.rom.on.ca. Royal Ontario Museum. 2011-06-10. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- ^ Slind, O.L., Andrews, G.D., Murray, D.L., Norford, B.S., Paterson, D.F., Salas, C.J., and Tawadros, E.E., Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists and Alberta Geological Survey (1994). "The Geological Atlas of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin (Mossop, G.D. and Shetsen, I., compilers), Chapter 8: Middle Cambrian and Early Ordovician Strata of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin". Archived from the original on 2016-07-01. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Caron, J. -B.; Gaines, R. R.; Mangano, M. G.; Streng, M.; Daley, A. C. (2010). "A new Burgess Shale-type assemblage from the "thin" Stephen Formation of the southern Canadian Rockies". Geology. 38 (9): 811–814. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..811C. doi:10.1130/G31080.1. Archived from the original on 2023-12-07. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ Fletcher, T. P.; Collins, D. (1998). "The Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale and its relationship to the Stephen Formation in the southern Canadian Rocky Mountains". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 35 (4): 413–436. Bibcode:1998CaJES..35..413F. doi:10.1139/cjes-35-4-413.

- ^ McCormick, Cole A.; Corlett, Hilary; Roberts, Nick M. W.; Johnston, Paul A.; Collom, Christopher J.; Stacey, Jack; Koeshidayatullah, Ardiansyah; Hollis, Cathy (2024-06-13). "U-Pb geochronology reveals that hydrothermal dolomitization was coeval to the deposition of the Burgess Shale lagerstätte". Communications Earth & Environment. 5 (1): 318. Bibcode:2024ComEE...5..318M. doi:10.1038/s43247-024-01429-0. ISSN 2662-4435.

- ^ Briggs, Derek E. G.; Collins, Desmond (1999). "The Arthropod Alalcomenaeus cambricus Simonetta, from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia". Palaeontology. 42 (6): 953–977. Bibcode:1999Palgy..42..953B. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00104. ISSN 0031-0239. S2CID 129399862.

- ^ Rigby, J. K.; Collins, D. (2004). "Sponges of the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale and Stephen Formations, British Columbia". ROM contributions in science. 1. ISBN 0-88854-443-X. ISSN 1710-7768.

- ^ a b c d Caron, Jean-Bernard; Jackson, Donald A. (October 2006). "Taphonomy of the Greater Phyllopod Bed community, Burgess Shale". PALAIOS. 21 (5): 451–65. Bibcode:2006Palai..21..451C. doi:10.2110/palo.2003.P05-070R. JSTOR 20173022. S2CID 53646959.

- ^ S. Conway Morris & D. H. Collins (1996). "Middle Cambrian ctenophores from the Stephen Formation, British Columbia, Canada". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 351 (1337): 243–360. doi:10.1098/rstb.1996.0024. JSTOR 56388.

- ^ Nanglu, K.; Caron, J.; Conway Morris, S.; Cameron, C. (2016). "Cambrian suspension-feeding tubicolous hemichordates". BMC Biology. 14 (56): 56. doi:10.1186/s12915-016-0271-4. PMC 4936055. PMID 27383414.

- ^ Steven T. LoDuca; Jean-Bernard Caron; James D. Schiffbauer; Shuhai Xiao & Anthony Kramer (2015). "A reexamination of Yuknessia from the Cambrian of British Columbia and Utah". Journal of Paleontology. 89 (1): 82–95. Bibcode:2015JPal...89...82L. doi:10.1017/jpa.2014.7. S2CID 129248278.

- ^ a b Butterfield, N.J. (1990). "A reassessment of the enigmatic Burgess Shale fossil Wiwaxia corrugata (Matthew) and its relationship to the polychaete Canadia spinosa. Walcott". Paleobiology. 16 (3): 287–303. Bibcode:1990Pbio...16..287B. doi:10.1017/S0094837300010009. JSTOR 2400789. S2CID 88100863.

- ^ Budd, G. E.; Jensen, S. (2000). "A critical reappraisal of the fossil record of the bilaterian phyla". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 75 (2): 253–95. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1999.tb00046.x. PMID 10881389. S2CID 39772232.

- ^ Conway Morris, S. (1985). "The Middle Cambrian metazoan Wiwaxia corrugata (Matthew) from the Burgess Shale and Ogygopsis Shale, British Columbia, Canada". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 307 (1134): 507–582. Bibcode:1985RSPTB.307..507M. doi:10.1098/rstb.1985.0005. JSTOR 2396338.

- ^ Holmer, L. E.; Caron, J. B. (2006). "A spinose stem group brachiopod with pedicle from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale". Acta Zoologica. 87 (4): 273. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.2006.00241.x.

- ^ Van Iten, H.; Zhu, M. Y.; Collins, D. (2002). "First Report of Sphenothallus Hall, 1847 in the Middle Cambrian". Journal of Paleontology. 76 (5): 902–905. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2002)076<0902:FROSHI>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1307202. S2CID 131018299.

- ^ Moon, Justin; Caron, Jean-Bernard; Moysiuk, Joseph (2023-08-09). "A macroscopic free-swimming medusa from the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 290 (2004). doi:10.1098/rspb.2022.2490. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 10394413. PMID 37528711.

- ^ Gee, Henry (2018). Across the Bridge: Understanding the Origin of the Vertebrates. University of Chicago Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-226-40319-9. Archived from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- ^ "Steiner, M., Fatka, O., 1996, Lower Cambrian tubular micro- to macrofossils from the Paseky Shale of the Barrandian area (Czech Republic): Paläontologische Zeitschrift, v, 70, p. 275–299" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-26.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Carroll Lane Fenton (1943). "Pre-Cambrian and Early Paleozoic algae". American Midland Naturalist. 30 (1): 83–111. doi:10.2307/2421265. JSTOR 2421265.

- ^ Wu, Mengyin; Loduca, Steven T.; Zhao, Yuanlong; Xiao, Shuhai (2016). "The macroalga Bosworthia from the Cambrian Burgess Shale and Kaili biotas of North America and China". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 230: 47–55. Bibcode:2016RPaPa.230...47W. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2016.04.001.

- ^ Durham, J. W. (1974). "Systematic Position of Eldonia ludwigi Walcott". Journal of Paleontology. 48 (4): 750–755. JSTOR 1303225.

- ^ Conway Morris, S. (1979). "The Burgess Shale (Middle Cambrian) Fauna". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 10: 327–349. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.10.110179.001551.

- ^ Zhao, Yang; Vinther, Jakob; Parry, Luke A.; Wei, Fan; Green, Emily; Pisani, Davide; Hou, Xianguang; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Cong, Peiyun (2019-04-01). "Cambrian Sessile, Suspension Feeding Stem-Group Ctenophores and Evolution of the Comb Jelly Body Plan". Current Biology. 29 (7): 1112–1125.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.036. hdl:1983/40a6bcb8-a740-482c-a23c-7d563faea5c5. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 30905603.