Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe

| Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued January 9, 1978 Decided March 6, 1978 | |

| Full case name | Mark Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe |

| Citations | 435 U.S. 191 (more) 98 S. Ct. 1011, 55 L. Ed. 2d 209, 1978 U.S. LEXIS 66 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Oliphant v. Schlie, 544 F.2d 1007 (9th Cir. 1976); cert. granted, 431 U.S. 964 (1977). |

| Subsequent | Oliphant v. Schlie, 573 F.2d 1137 (9th Cir. 1978). |

| Holding | |

| Indian tribal courts do not have inherent criminal jurisdiction to try and to punish non-Indians and hence may not assume such jurisdiction unless specifically authorized to do so by Congress. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Rehnquist, joined by Stewart, White, Blackmun, Powell, Stevens |

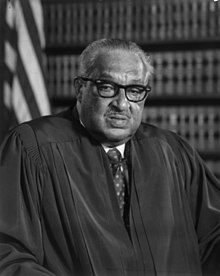

| Dissent | Marshall, joined by Burger |

| Brennan took no part in the consideration or decision of the case. | |

Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978), is a United States Supreme Court case deciding that Indian tribal courts have no criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians.[1] The case was decided on March 6, 1978 with a 6–2 majority. The court opinion was written by William Rehnquist, and a dissenting opinion was written by Thurgood Marshall, who was joined by Chief Justice Warren Burger. Justice William J. Brennan did not participate in the decision.

Congress partially abrogated the Supreme Court's decision by enacting the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013, which recognizes the criminal jurisdiction of tribes over non-Indian perpetrators of domestic violence that occur in Indian Country when the victim is Indian.[2]

Background

[edit]In August 1973 Mark David Oliphant, a non-Indian living as a permanent resident with the Suquamish Tribe on the Port Madison Indian Reservation in northwestern Washington,[3] was arrested and charged by tribal police with assaulting a tribal officer and resisting arrest during the Suquamish Tribe's Chief Seattle Days.[4] Knowing that thousands of people would gather in a small area for the celebration, the tribe requested Kitsap County and the Bureau of Indian Affairs for additional law enforcement assistance.[5] The county sent just one deputy, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs sent no one. When Oliphant was arrested, at 4:30 a.m., only tribal officers were on duty.[5]

Oliphant applied for a writ of habeas corpus in federal court and claimed he was not subject to tribal authority because he was not Native American. He challenged the exercise of criminal jurisdiction by the tribe over non-Indians.[4][6]

Procedural history

[edit]Oliphant's application for a writ of habeas corpus was rejected by the lower courts. The Ninth Circuit upheld tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians on Indian land because the ability to keep law and order on tribal lands was an important attribute of tribal sovereignty[7] that had been neither surrendered by treaty nor removed by the US Congress under its plenary power over Tribes.[8] Judge Anthony Kennedy, then a judge of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, dissented from the decision and said he found no support for the idea that only treaties and acts of Congress could take away the retained rights of tribes. He considered that doctrine of tribal sovereignty was not "analytically helpful" in resolving the issue.[9][6]

Ruling

[edit]The Supreme Court ruled in Oliphant's favor by holding that Indian tribal courts do not have criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians for conduct occurring on Indian land and reversed the Ninth Circuit's decision.[1] More broadly, the Supreme Court held that Indian tribes cannot exercise powers "expressly terminated by Congress" or "inconsistent with their status" as "domestic dependent nations."[10]

Analyzing the history of Congressional actions related to criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country, the Supreme Court concluded that there was an "unspoken assumption" that tribes lacked criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians.[11] While "not conclusive," the "commonly shared presumption of Congress, the Executive Branch, and lower federal courts that tribal courts do not have the power to try non-Indians carrie[d] considerable weight."[12]

The Court incorporated that presumption into its analysis of the Treaty of Point Elliot, which was silent on the issue of tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians. The Court rejected the Ninth Circuit's approach, which interpreted the treaty's silence in favor of tribal sovereignty and applied the "long-standing rule that legislation affecting the Indians is to be construed in their interest."[13] Instead, the Court revived the doctrine of implicit divestiture. Citing Johnson v. McIntosh and Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, the Court considered criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians an example of the "inherent limitations on tribal powers that stem from their incorporation into the United States," similar to tribes' abrogated rights to alienate land.[14]

By incorporating into the United States, the Court found that Tribes "necessarily [gave] up their power to try non-Indian citizens of the United States except in a manner acceptable to Congress". Arguing that non-Indian citizens should not be subjected to another sovereign's "customs and procedure", the Court analogizes to Crow Dog. In Crow Dog, which was decided before the Major Crimes Act, the Court found exclusive Tribal jurisdiction over Tribe-members because it would be unfair to subject Tribe-members to an "unknown code" imposed by people of a different "race [and] tradition" from their own.[15]

Although the Court found no inherent Tribal criminal jurisdiction, it acknowledged the "prevalence of non-Indian crime on today's reservations which the tribes forcefully argue requires the ability to try non-Indians" and invited "Congress to weigh in" on "whether Indian tribes should finally be authorized to try non-Indians".[16]

Dissenting opinion

[edit]

Justice Thurgood Marshall dissented. In his view, the right to punish all individuals who commit crimes against tribal law within the reservation was a necessary aspect of the tribe's sovereignty:[17]

I agree with the court below that the "power to preserve order on the reservation ... is a sine qua non of the sovereignty that the Suquamish originally possessed." Oliphant v. Schlie, 544 F.2d 1007, 1009 (CA9 1976). In the absence of affirmative withdrawal by treaty or statute, I am of the view that Indian tribes enjoy, as a necessary aspect of their retained sovereignty, the right to try and punish all persons who commit offenses against tribal law within the reservation. Accordingly, I dissent.[17]

Chief Justice Warren Burger joined the dissenting opinion.[17]

Effects

[edit]In 1990 the Supreme Court extended Oliphant to hold that tribes also lacked criminal jurisdiction over Indians who were not members of the tribe, exercising jurisdiction in Duro v. Reina.[3] Within six months, however, Congress abrogated the decision by amending the Indian Civil Rights Act to affirm that tribes had inherent criminal jurisdiction over nonmember Indians.[18][19] In 2004, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the legislation in United States v. Lara.[18]

Scholars have extensively criticized Oliphant. According to Professor Bethany Berger, "By patching together bits and pieces of history and isolated quotes from nineteenth century cases, and relegating contrary evidence to footnotes or ignoring it altogether, the majority created a legal basis for denying jurisdiction out of whole cloth." Rather than legal precedent, the holding was "dictated by the Court's assumptions that tribal courts could not fairly exercise jurisdiction over outsiders and that the effort to exercise such jurisdiction was a modern upstart of little importance to tribal concerns."[20] Professor Philip Frickey describes Oliphant, along with the subsequent decisions limiting tribal jurisdiction over non-Indians, as rooted in a "normatively unattractive judicial colonial impulse,"[21] and Professor Robert Williams condemns the decision as "legal auto-genocide."[22] According to Dr. Bruce Duthu, the case showed "that the project of imperialism is alive and well in Indian Country and that courts can now get into the action."[23]

The Oliphant Court essentially elevated a local level conflict between a private citizen and an Indian tribe into a collision of framework interests between two sovereigns, and in the process revived the most negative and destructive aspects of colonialism as it relates to Indian rights. This is a principal reason the decision has attracted so much negative reaction ... Oliphant's impact on the development of federal Indian law and life on the ground in Indian Country has been nothing short of revolutionary. The opinion gutted the notion of full territorial sovereignty as it applies to Indian tribes.[24]

Evolution

[edit]Congress allowed the tribal courts the right to consider a lawsuit if a non-Indian man commits domestic violence towards a Native American woman on the territory of a Native American tribe by passing Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (VAWA 2013), signed into law on March 7, 2013, by President Barack Obama. It was motivated by the high percentage of Native American women being assaulted by non-Indian men, who felt immune because of the lack of jurisdiction of tribal courts. The new law allowed tribal courts to exercise jurisdiction over non-Indian domestic violence offenders but also imposed other obligations on tribal justice systems, including the requirement for tribes to provide licensed attorneys to defend the non-Indians in tribal court. The new law took effect on March 7, 2015, but also authorized a voluntary "Pilot Project" to allow certain tribes to begin exercising special jurisdiction earlier.[25] On February 6, 2014, three tribes were selected for this Pilot Project:[26] the Pascua Yaqui Tribe (Arizona), the Tulalip Tribes of Washington, and the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (Oregon).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191, 195 (1978).

- ^ 25 U.S.C. § 1304, VAWA Reauthorization Act available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-113s47enr/pdf/BILLS-113s47enr.pdf

- ^ a b French, Laurence Armand. Native American Justice. Chicago, IL: Burnham Inc., Publishers, 2003. pg. 59

- ^ a b 435 U.S. at 194.

- ^ a b Oliphant v. Schlie, 544 F.2d 1007, 1013 (9th Cir. 1976), rev'd sub nom. Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978) (quoting appellees' brief, pages 27-28)

- ^ a b Duthu, N. Bruce. American Indians and the Law. New York, NY: Penguin Group, 2008. p.19

- ^ Oliphant v. Schlie, 544 F.2d at 1009 ("Surely the power to preserve order on the reservation, when necessary by punishing those who violate tribal law, is a sine qua non of the sovereignty that the Suquamish originally possessed.")

- ^ Oliphant v. Schlie, 544 F.2d at 1010–1012.

- ^ Oliphant v. Schlie, 544 F.2d at 1015.

- ^ 435 U.S. at 208-09 (internal quotations omitted).

- ^ 435 U.S. at 201–206.

- ^ 435 U.S. at 206.

- ^ Oliphant v. Schlie, 544 F.2d at 1010.

- ^ 435 U.S. at 209.

- ^ 435 U.S. at 210–11 (quoting Ex parte Crow Dog, 109 U.S. 556, 571 (1883)).

- ^ 435 U.S. at 212.

- ^ a b c 435 U.S. at 212 (Marshall, J., dissenting).

- ^ a b Bethany R. Berger, U.S. v. Lara as a Story of Native Agency, 40 Tulsa L. Rev. 5 (2004).

- ^ Philip S. Deloria & Nell Jessup Newton, The Criminal Jurisdiction of Tribal Courts over Non-Member Indians: An Examination of the Basic Framework of Inherent Tribal Sovereignty Before and After Duro v. Reina, 38 Fed. B. News & J. 70, 70-71 (1991).

- ^ Bethany R. Berger, Justice and the Outsider: Jurisdiction over Nonmembers in Tribal Legal Systems, 37 Ariz. St. L.J. 1047, 1050–51 (2005).

- ^ Philip P. Frickey, A Common Law for Our Age of Colonialism: The Judicial Divestiture of Indian Tribal Authority Over Nonmembers, 109 Yale L.J. 1, 7 (1999).

- ^ Robert A. Jr. Williams, The Algebra of Federal Indian Law: The Hard Trail of Decolonizing and Americanizing the White Man's Indian Jurisprudence, 1986 Wis. L. Rev. 219, 274 (1986).

- ^ Duthu, supra, at 21.

- ^ Duthu, supra, at 20–21.

- ^ Department of Justice, "Tribal Justice and Safety"

- ^ Department of Justice, "Justice Department Announces Three Tribes to Implement Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction Under VAWA 2013"

Further reading

[edit]- Russel Lawrence Barsh & James Youngblood Henderson, The Betrayal: Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe and the Hunting of the Snark, 63 Minn. L. Rev. 609 (1979).

- Bethany R. Berger, U.S. v. Lara as a Story of Native Agency, 40 Tulsa L. Rev. 5 (2004).

- Bethany R. Berger, Justice and the Outsider: Jurisdiction over Nonmembers in Tribal Legal Systems, 37 Ariz. St. L.J. 1047, 1050–51 (2005).

- Philip P. Frickey, A Common Law for Our Age of Colonialism: The Judicial Divestiture of Indian Tribal Authority Over Nonmembers, 109 Yale L.J. 1 (1999).

- Paul Spruhan, "Indians in a Jurisdictional Sense: Tribal Citizenship and other Forms of non-Indian Consent to Tribal Criminal Jurisdiction", 1 American Indian Law Journal 79 (2012) https://ssrn.com/abstract=2179149

- Robert A. Jr. Williams, The Algebra of Federal Indian Law: The Hard Trail of Decolonizing and Americanizing the White Man's Indian Jurisprudence, 1986 Wis. L. Rev. 219 (1986).

- Judith Resnik, Dependent Sovereigns: Indian Tribes, States, and the Federal Courts, 56 U. Chicago L. Rev. 671 (1989).

- Snyder-Joy, Zoaan K. (1995). "Self-Determination and American Indian Justice: Tribal versus Federal Jurisdiction on Indian Lands". In Hawkins, Darnell F. (ed.). Ethnicity, Race, and Crime: Perspectives Across Time and Place. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. pp. 310–322. ISBN 0-7914-2195-3.

External links

[edit]- Text of Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978) is available from: CourtListener Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)