New York Crystal Palace

| New York Crystal Palace | |

|---|---|

New York Crystal Palace designed by Karl Gildemeister and Georg Carstensen. The image is an "oil-color" plate by George Baxter, London, dated September 1, 1853 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Destroyed |

| Type | Exhibition palace |

| Town or city | New York City |

| Country | United States of America |

| Coordinates | 40°45′13″N 73°59′02″W / 40.75361°N 73.98389°W |

| Inaugurated | July 14, 1853 |

| Destroyed | October 5, 1858 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Georg Carstensen and Charles Gildemeister |

New York Crystal Palace was an exhibition building constructed for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York City in 1853, which was under the presidency of the mayor Jacob Aaron Westervelt. The building stood on a site behind the Croton Distributing Reservoir in what is now Bryant Park. It was destroyed by fire on October 5, 1858.

Use in the exhibition

[edit]New York City's 1853 Exhibition was held on a site behind the Croton Distributing Reservoir, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues on 42nd Street, in what is today Bryant Park in the borough of Manhattan. The New York Crystal Palace was designed by Georg Carstensen and German architect Charles Gildemeister, and was directly inspired by The Crystal Palace built in London's Hyde Park to house The Great Exhibition of 1851. The New York Crystal Palace had the shape of a Greek cross, and was crowned by a dome 100 ft (30 m) in diameter. Like the Crystal Palace of London, it was constructed from iron and glass. Construction was handled by engineer Christian Edward Detmold.[1] Horatio Allen was the consulting engineer, and Edmund Hurry the consulting architect.[2]

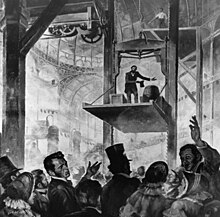

President Franklin Pierce spoke at the dedication on July 14, 1853. Theodore Sedgwick was the first president of the Crystal Palace Association. After a year, he was succeeded by Phineas T. Barnum who put together a reinauguration in May 1854 when Henry Ward Beecher and Elihu Burritt were the featured orators. This revived interest in the Palace, but by the end of 1856 it was a dead property.[2] Elisha Otis demonstrated the safety elevator, which prevented the fall of the cab if the cable broke, at the Crystal Palace in 1854 in a dramatic presentation.[3]

Observatory

[edit]The adjoining Latting Observatory, a wooden tower 315 feet (96 m) high, allowed visitors to see into Queens to the east, Staten Island to the south, and New Jersey to the west. The tower, taller than the spire of Trinity Church at 290 feet (88 m), was the tallest structure in New York City from the time it was constructed in 1853 until it was shortened in 1855; it burned down in 1856.[4][5] The Crystal Palace itself barely escaped destruction.

Destruction

[edit]

The New York Crystal Palace was destroyed by fire on October 5, 1858, during the American Institute Fair held there. The fire began in a lumber room on the side adjacent to 42nd Street. Within fifteen minutes its dome fell and in twenty-five minutes the entire structure had burned to the ground. There were no deaths but the loss of property amounted to more than $350,000 (equivalent to $12,325,000 in 2023). This included the building, valued at $125,000 (equivalent to $4,402,000 in 2023), and exhibits and valuable statuary remaining from the World's Fair.[6]

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ a b New-York Crystal Palace.; A Famous Enterprise Recalled by the Death of its Chief Promoter, from The New York Times, July 5, 1887.

- ^ The Elevator Museum, timeline Archived January 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine; "Skyscrapers" Magical Hystory Tour: The Origins of the Commonplace & Curious in America (September 1, 2010).

- ^ Pollak, Michael. "F.Y.I.: Over the Bounding Pond", The New York Times, August 28, 2005. Accessed May 18, 2009.

- ^ Staff. "New-York City; A Conflagration--Destruction of the "Latting Observatory"--$130,000 worth of Property destroyed-Narrow escape of the Crystal Palace. The Knife Again--Probable Murder of a Boy by a Boy. Police Intelligence. Burned to Death.", The New York Times, September 1, 1856. Accessed May 18, 2009.

- ^ New York Times, Other Burned Theatres, December 7, 1876, Page 10.

- Bibliography

- Burrows, Edwin G. The Finest Building in America: The New York Crystal Palace 1853-1858 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018) ISBN 9780190681210

- Carstensen & Gildemeister, New York Crystal Palace: illustrated description of the building by Geo. Carstensen & Chs. Gildemeister, architects of the building; with an oil-color exterior view, and six large plates containing plans, elevations, sections, and details, from the working drawings of the architects (New York: Riker, Thorne & co., 1854)

- CUNY Graduate Center, "Crystal Palace/42 Street/1853-54"; Catalogue by Linda Hyman of an exhibition mounted at the Graduate Center Mall from October 7 to 26, 1974. [36] pp, 22 b/w illustrations, bibliographic note. (New York: CUNY Graduate Center, 1974)

External links

[edit]- New York Crystal Palace:1853. Digital Publication, Bard Graduate Center. March 24, 2017.

- "1853-54 New York: Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations". World's Fair Overview 1851-1970. University of Maryland Libraries. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- History of Bryant Park Archived October 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- The Great Crystal Palace Fire of 1858 from the Museum of the City of New York Collections blog

- The New York Crystal Palace Records at the New York Historical Society

- Event venues in Manhattan

- Burned buildings and structures in the United States

- Commercial buildings completed in 1853

- Demolished buildings and structures in Manhattan

- World's fair architecture in New York City

- World's fairs in New York City

- 19th century in New York City

- 1850s fires in North America

- 1858 fires

- 19th-century fires in the United States

- Bryant Park buildings

- Commercial building fires in New York City

- Building and structure collapses in New York

- Building and structure collapses caused by fire