Jean-Étienne Liotard

Jean-Étienne Liotard (French pronunciation: [ʒɑ̃n‿etjɛn ljɔtaʁ]; 22 December 1702 – 12 June 1789) was a Genevan[1] painter, art connoisseur and dealer. He is best known for his detailed, strikingly naturalistic portraits in pastel, and for the works from his stay in Turkey. A Huguenot of French origin and citizen of the Republic of Geneva,[2] he was born and died in Geneva, but spent most of his career in stays in the capitals of Europe, where his portraits were much in demand. He worked in Rome, Istanbul, Paris, Vienna, London, and other cities.

Life

[edit]

Liotard was born in Geneva. His parents were French Protestants who had fled to Geneva after 1685.[3] Jean-Étienne Liotard began his studies under professors Daniel Gardelle and Petitot, whose enamels and miniatures he copied with considerable skill.[4]

He went to Paris in 1725, studying under Jean-Baptiste Massé and François Lemoyne, on whose recommendation he was taken to Naples by the vicomte de Puysieux, Louis Philogène Brulart, Marquis de Puysieulx and Comte de Sillery. In 1735 he was in Rome, painting the portraits of Pope Clement XII and several cardinals.[4] In 1738 he accompanied Lord Duncannon to Constantinople, where he worked for the next four years.[5]

Liotard visited Istanbul and painted numerous pastels of Turkish domestic scenes; he also continued to wear Turkish dress for much of the time when back in Europe. Using modern dress was considered unheroic and inelegant in history painting using Middle Eastern settings, with Europeans wearing local costume, as travellers were advised to do.

Many travellers had themselves painted in exotic Eastern dress on their return, including Lord Byron, as did many who had never left Europe, including Madame de Pompadour.[6] Byron's poetry was highly influential in introducing Europe to the heady cocktail of Romanticism in exotic Oriental settings which was later to dominate 19th century Oriental art.

His eccentric adoption of oriental costume secured him the nickname of the Turkish painter.[5]

He went to Vienna in 1742 to paint the portraits of the Imperial family.[4] In 1745 he sold La belle chocolatière to Francesco Algarotti.

Still under distinguished patronage [citation needed] he returned to Paris. In 1753 he visited England, where he painted Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, the Princess of Wales. He went to Holland in 1756, where, in the following year, he married Marie Fargues.[4] She also came from a Huguenot family, and wanted him to shave off his beard.

In 1762 he painted portraits in Vienna, including Marie Antoinette; in 1770 in Paris. Another visit to England followed in 1772, and in the next two years his name figures among the Royal Academy exhibitors. He returned to his native town in 1776.[4] In 1781 Liotard published his Traité des principes et des règles de la peinture. In his last days he painted still lifes and landscapes. He died at Geneva in 1789.

Works

[edit]Liotard was an artist of great versatility. Best known for his graceful and delicate pastel drawings,[7] of which La Liseuse, The Chocolate Girl, and La Belle Lyonnaise at the Dresden Gallery and Maria Frederike van Reede-Athlone at Seven at the J. Paul Getty Museum are delightful examples, he also achieved distinction for his enamels, copperplate engravings, and glass painting. Additionally, he wrote a Treatise on the Art of Painting and was an expert collector of paintings by the old masters.[4]

Many of the masterpieces he had acquired were sold by him at high prices on his second visit to England. The museums of Amsterdam, Bern, and Geneva are particularly rich in examples of his paintings and pastel drawings. A picture of a Turk seated is at the Victoria and Albert Museum, while the British Museum owns two of his drawings.[4]

The Louvre has, besides twenty-two drawings, a portrait of Lieutenant General Hérault as well as an oil painting of an English merchant and a friend dressed in costumes and entitled Monsieur Levett and Mademoiselle Helene Glavany in Turkish Costumes. A portrait of the artist is to be found at the Sala di pittori, in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. As his son also married a Dutch girl, the Rijksmuseum inherited an important collection of his drawings and paintings.

One outstanding feature of Liotard's paintings is the prevalence of smiling subjects. Generally, portrait subjects of the time adopted a more serious tone. This levity was a reflection of the Enlightenment-era philosophies that inspired Liotard.[7] Also indicative of the era, Liotard created works celebrating science, like the painting of woman paying homage to the doctor that saved her.[7]

Pastel medium

[edit]Liotard, also known as ‘le peintre de la verité’, chose the medium of pastel, in order to give his paintings a naturalistic effect. Liotard's Apollo and Daphne and The Three Graces might be his oldest pastel works that have been remained.[8] While Liotard mainly worked with oil paint in Paris, one can say Liotard's career as pastellist officially begun in Italy. Liotard had already been familiar with the medium of pastel during his younger years which he spent in his hometown Geneva, but it was not the medium he officially worked in. The rejection that Liotard received from the Académie Royale de Peinture in Paris on his historical works in oil paint may have been a stimulus for him to go back to his beloved medium, in which he was notably more skilled.

In his treatise Liotard mentions the importance of l’élimination des touches, in order to provide a realistic imitation of nature. The invisibility of brushstrokes could be achieved more easily by the use of pastel instead of oil paint.[9] It is thus unquestionable that Liotard chose the pastel medium because of its ability to imitate nature, which he found the most important aspect of painting. For the same reason, Diderot mentions that pastel is the best medium for portraiture in his Dictionnaire Raisonné of 1751, when the popularity of pastel as an artistic medium was at its peak.[10]

The proportions of pastel result in a particularly dry material that affords intense and vibrant colours, which Liotard valued working with. "For its beauty, vivacity, freshness and lightness of palette," Liotard wrote, "pastel painting is more beautiful than any other kind of painting."[11] Liotard is known for pressing pastel quite forcefully onto the paper to create extra brilliance in order to exaggerate these qualities. This peculiar technique and desire for luminosity is what set him apart from other artists working with pastel and makes his works unique.

Support and fixatives

[edit]Liotard mostly used vellum, a surface made from the skin of calves, goats and lambs, for his pastel works as it retains the brilliance of the pigment best. He often prepared his support with fish glue and wine, mixed with fine pumice dust.[12] In the eighteenth century pastel was often supported by coloured paper, especially blue thick paper was popular as it enhanced the brilliance of pastel. According to Gombaud and Sauvage, Liotard also often used blue paper when working on a paper support.

The vast majority of pastels that survive from the eighteenth century were not fixed.[13] The powdery pigment is applied dry, which makes it quite brittle. This allows the pigment to easily detach from its surface, but also makes it more sensitive to moisture and stains. This factor complicates the conservation of pastel works.

- Selected works

-

Richard Pococke, 1738–39, oil on canvas

-

The Chocolate Girl, 1743–1744

-

Count Francesco Algarotti, 1745, pastel on parchment

-

Marie Charlotte Boissier, 1746

-

Jeanne-Elisabeth de Sellon, c. 1746, pastel on parchment

-

Portrait of Monsieur Boère, merchant from Genoa, 1746, pastel on parchment

-

Empress Maria Theresia, 1747, enamel on copper

-

Portrait of Mademoiselle Jacquet, c. 1748–1752, pastel on paper

-

Marie Josèphe von Sachsen, 1749, pastel on vellum

-

Self-portrait, c. 1749, pastel

-

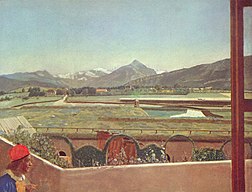

Landschaft bei Genf, 1750

-

A Turkish Lady and her Servant, 1750, oil on canvas

-

Marie Adelaide of France in Turkish Dress, 1753, oil on canvas

-

Portrait of Frederick, Prince of Wales, 1754, pastel on vellum

-

The first Cup, 1754, pastel on vellum

-

Maria Frederike van Reede-Athlone, 1755–56, pastel on vellum

-

Portrait of dr François Tronchin, 1757, pastel on parchment. Tronchin is looking at Rembrandt's Woman in Bed

-

Ami-Jean de la Rive, c. 1758, pastel on paper

-

Portrait of a Young Woman, pastel

-

Portrait of Marthe Marie Tronchin, c. 1758 (Art Institute Chicago)

-

Portrait of Madame Jean Tronchin (née Anne Molènes), 1758

-

Portrait of Madame François Tronchin (née Anne-Marie Fromaget), 1758

-

Le petit déjeuner de la famille Lavergne, 1754

-

Henry Frederick, Duke of Cumberland, 1754

-

Portrait of Princess Louisa of Great Britain, 1754

-

Marianne Liotard Holding a Doll, 1765

-

(c. 1770)

-

1773

-

Still Life, Tea Set, c. 1781–83, oil on canvas

-

Still life with Figs, 1782, pastel

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ According to the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland and to his biographical notice on the official website of the Canton of Geneva, Jean-Etienne Liotard was a citizen of the Republic of Geneva and a deputy there in one of the republic councils (Council of Two Hundred). Also see page 191 in [1]. His country of origin is sometimes (for instance in ULAN) referred to as being Switzerland.

- ^ La Vendée La Terreur « Enquête sur l’histoire », trimestrial publication, Winter 93, number 5, p.74.

- ^ Parmantier-Lallement, N. "Liotard, Jean-Etienne". Grove Art Online.

- ^ a b c d e f g One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Liotard, Jean Etienne". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 739.

- ^ a b Baetjer, Katharine, and Marjorie Shelley. 2011. Pastel Portraits: Images of 18th-century Europe. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780300169812.

- ^ Christine Riding, Travellers and Sitters: The Orientalist Portrait, in Tromans, 48–75

- ^ a b c Jonathan Jones, Jean-Etienne Liotard review – a joyous time machine back to the Enlightenment, The Guardian, 20 October 2015.

- ^ Bull, Duncan; Bunt, Thomas Macsotay Bunt (2002). Jean-Etienne Liotard (1703-1789). Zwolle: Waanders Drukkers. p. 10.

- ^ Liotard, J.E. (1945). Traité des principes et des règles de la peinture. Genève: Pierre Cailler. p. 92.

- ^ Diderot, Dennis; et al. (1751). Encyclopédie, ou, Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. Paris: Chez Briasson; David l'Aîné, Le Breton; Durand. p. 154.

- ^ Liotard, J.E. (1762). Explications des différens jugement sur la peinture. Mercure de France. p. 186.

- ^ Sauvage, Leila; Gombaud, Cécile (2015). "Liotard's Pastels: Techniques of an 18th-century Pastellist". Technology and Practice – Studying 18th century paintings and art on paper, CATS Proceedings, 2015. pp. 31–45. ISBN 978-1-909492-23-3.

- ^ Shelley, Marjorie (2011). "Paintin in the Dry Manner: The Flourishing of Pastel in 18th-Century Europe". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 68: 37.

External links

[edit]- Short biography

- 74 works by Liotard at the Musées d'Art et d'Histoire, Geneva

- Some paintings of Liotard in the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum

- Liotard on a Danish website

- Liotard in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800, online edition

- Liotard paintings at The J. Paul Getty Museum