History of the Jews in Madagascar

Jiosy Gasy Juifs Malgaches מָדָגַסְקָר סְפָרַד (Madagascar Sepharad) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 360 (approximate)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Madagascar: Mainly in Ampanotokana. | |

| Languages | |

| Malagasy, Hebrew, French | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Malagasy peoples, Sephardi Jews |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

| History of Madagascar |

|---|

|

|

Uncertain accounts of Jews in Madagascar go back to the earliest ethnographic descriptions of the island, from the mid-17th century. Madagascar has a small Jewish population, including normative adherents as well as Judaic mystics, but the island has not historically been a significant center for Jewish settlement. Despite this, an enduring origin myth across Malagasy ethnic groups suggests that the island's inhabitants descended from ancient Jews, and thus that the modern Malagasy and Jewish peoples share a racial affinity. This belief, termed the "Malagasy secret", is so widespread that some Malagasy refer to the island's people as the Diaspora Jiosy Gasy (Malagasy Jewish Diaspora). As a result, Jewish symbols, paraphernalia, and teachings have been integrated into the syncretic religious practices of some Malagasy populations. Similar notions of Madagascar's supposed Israelite roots persisted in European chronicles of the island until the early 20th century, and may have influenced a Nazi plan to relocate Europe's Jews to Madagascar. More recently, the possibility of Portuguese Jewish conversos making contact with Madagascar in the 15th century has been proposed.

Madagascar's small Jewish community faced challenges during the Vichy regime, which implemented antisemitic laws affecting the few Jews on the island. In the 21st century, some indigenous Malagasy communities informally identified with Jews and Judaism have adopted rabbinic Judaism, studying the Torah and Talmud across three small congregations and undergoing Orthodox conversion. The unified rabbinic Jewish community practices a Sephardic liturgy and refers to its ethnic division within Judaism as Madagascar Sepharad.

Theories of Jewish origin of Malagasy people

[edit]

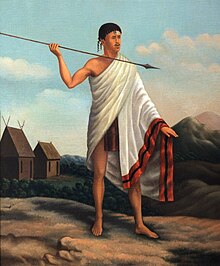

The "Malagasy secret"

[edit]There is a widespread, centuries-old[2] belief in Madagascar that Malagasy people are descended from Jews, with "probably millions" of people in Madagascar claiming genealogical origins in ancient Israel.[3] This belief is termed the "Malagasy secret", and is so common that some Malagasy refer to their people(s) as the Diaspora Jiosy Gasy (Malagasy Jewish Diaspora).[4] The origin myths, which vary across clans, often include ancestors arriving at the shores of Madagascar wearing white and bearing "red zebu", a localized adaptation of the biblical red heifer tradition.[5][6] Katherine Quanbeck records an oral testimony from a man of the Tavaratra clan, from Sandravinany, of his people's ancestors who...[5]

...came from somewhere in the area of Medina, or somewhere on the sea coast of Saudi Arabia, in scores of botries [boats] full of families to the northern coast of Madagascar. Some of them, the Tantakara, stayed in the area of that northern coast, others continued southward along the eastern coast of Madagascar. The dhow of our family contained one red zebu and when the dhow reached the Vohipeno area, the zebu brayed, so they stopped here temporarily. But then they continued southward, past what is known as Fort Dauphin, and continued on around the southern coast, even going as far as Androka. At the mouth of that river, the zebu brayed again, two times; so they stopped there but eventually left again, and returned the way they had come. After travelling back eastward along Madagascar’s southern coast, then northward along part of the eastern coast, at the Vohipeno area, the red zebu brayed three times. So they stopped there, and our family eventually moved as far south as Sandravinany, a region which was open totally, with no persons having settled it. We were the original Malagasy people in that area around what is now known as Sandravinany.

Further belief holds that Madagascar has been settled by Jews since ancient times, and that the island was associated with ancient Ophir.[7] These same legends assert that the rosewood used in the construction of the Temple of Solomon came from the lowland forests of Madagascar.[3]

Descent from members of this Solomonic fleet is prominently claimed by the Merina and Betsileo peoples.[8] Betsileo legend associated with a site called Ivolamena describes two Betsileo ancestors, Antos and Cathy, sent by Solomon to Madagascar to look for gold and precious stones.[9][10]

The Merina royal line has often claimed to descend from an ancient wave of Israelite migration that arrived via Asia in Madagascar, after being exiled by the Neo-Babylonian emperor Nebuchadnezzar.[11] Antemoro people claim Moses as their forebearer. Sakalava and Antandroy people explain certain taboos within their respective cultures as originating with ancient Israelite ancestors. Some Malagasy theories of Jewish provenance suggest ancestral origin in one or more of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, most commonly Gad, Issachar, Dan, and Asher. Another narrative linking ancient Hebrews to Madagascar asserts that Madagascar was the site of the Garden of Eden (with various island rivers around the Malagasy settlement of Mananzara cited as the true Biblical Pishon), and that Noah's Ark departed from Madagascar at the time of the flood.[12][13][10] One Antemoro legend recounts that the Islamic prophet Mahomet had five sons who all became kings in Arabia: Abraham, Noah, Joseph, Moses, and Jesus, the last four of them having fathered Tsimeto, Kazimambo, Anakara, and Raminia.[5]

Edith Bruder describes an oral testimony from the archives of Katherine Quanbeck, in which, "after several meetings," a young Sevohitse man "cautiously mentioned the existence of a place from where he came, Foibe Jiosy, which means 'the headquarters of the Jews,' near Ambovombe, Madagascar. He commented, 'We marry only within our clan. No one likes to come to our town. People do not like us. We have to hide the fact that we are Jewish.'"[5]

Similar "crypto-Jewish" legends exist in neighboring Comoros and Mozambique.[10]

Alakamisy Ambohimaha

[edit]

A site called Ivolamena in Alakamisy Ambohimaha contains cliffs that were studied in the 1950s by a team of French researchers following "rumors in the region of Fianarantsoa about the existence of letters carved in stone", discovered by local stonemason Edouard Randrianasolo.[9][8][14][10] The French researchers described an inscription on the cliff-face "imputable to characters derived from the Phoenician alphabet with a high probability that the [glyphs] emanate from the family of southern-Arabic [glyphs] called Sabaean." The team also hypothesized, based on commonalities between Sabaean and Malagasy irrigation techniques, that "Hamito-Semites" may have been the first to bring zebu cattle to Madagascar. Another nearby site, Vohisoratra (meaning 'the mountain with writings'), was reported to bear "an inscription calling to mind Hebrew characters." The researchers had received tips from a Malagasy informant, who suggested that the Vohisoratra inscriptions might be dated "to the time of king Solomon, who sent the Israelites across the world to seek precious stones for the building of Jerusalem".[8] In 1962, Pierre Vérin summarized scientific opinions of the inscriptions as "divided", and asserted that geologists consider the supposed inscriptions to be the products of "natural erosion".[8][15]

The Ivolamena and Vohisoratra sites[a] are today revered as a supernatural holy site by Betsileo claimants of ancient Israelite ancestry, who believe that both cliffs' inscriptions were left by their forebearers during a voyage to gather materials for Solomon's Temple during which they married the locals of a legendary "Zafindrandoto" tribe and settled to found the earliest Betsileo communities.[9][10] A January 1989 speech by then-president of Madagascar Didier Ratsiraka made reference to the local beliefs surrounding the Ambohimaha cliff, which he claimed bore "proto-Hebraïc" writings. Ratsiraka also reportedly requested that teams of Malagasy archaeologists investigate the question of Madagascar's Jewish roots and conduct digs in the Betsileo region to search for the biblical Queen of Sheba's treasure.[8] In 2009, residents of Alakamisy Ambohimaha threatened adherents of "Hebraic Judaism" who had come to the cliffs and sacrificed two lambs, one black and one white, despite the local fady (taboo) against slaughtering sheep.[9][16] The Betsileo locals called for the government to recognize the commune as a sacred site of historical heritage, and protect it accordingly.[16]

The "Jewish thesis"

[edit]

The theory that Malagasy people can trace their ancestry to ancient Jews—termed the "Jewish thesis"—is asserted in the earliest writings on the question of Malagasy origins, and by the late 19th and early 20th centuries had become a "conviction" of the many European chroniclers of the island.[8] Common substantiations for the thesis included observations of "linguistic similarities [between Hebrew and Malagasy]; common physiognomic traits; alimentary and hygiene taboos; some sort of monotheism [with the Malagasy naming Zanahary as their one, un-picturable God];[18] observance of a lunar calendar; and life-cycle events resembling those in the Jewish tradition, circumcision in particular".[19][8] A similar "Arab thesis" was also prevalent, though less persistent and popular than its Jewish counterpart.[6]

The British merchant Richard Boothby of the East India Company posited in 1646 that the people of Madagascar are descended from the Hebrew patriarch Abraham and his wife Keturah, and were sent away by Abraham to "inhabit the East".[20] The introduction (credited to Captain William Mackett) of Robert Drury's 1729 memoir suggests that "the Jew derived a great deal from [the Malagasy], instead of they from the Jews ... their religion is more ancient".[21] Samuel Copland wrote in 1822 that "The origin of the [Malagasy], is, by the generality of writers, ascribed to the Jews."[22][23] The naturalist Alfred Grandider affirmed supposed evidence of two waves of ancient Israelite migration to Madagascar in 1901, concluding: "The fleets sent by King Solomon towards the Southeast coast of Africa [to procure materials for his Temple] had probably some of their ships lost on the coasts of Madagascar and it is not unlikely that, in ancient times, some Jewish colonies had been founded, voluntarily or not, in this island."[8] Grandider also compared the cultural practices of the Malagasy to those of the ancient Israelites, finding in common thirty-five features including animal sacrifice, scapegoating, similar funerary conventions, and practices comparable to metzitzah b'peh and the ordeal of the bitter water.[24] That same year, Irish anthropologist Augustus Henry Keane published The Gold of Ophir: Whence Brought and by Whom?, in which he proposed that Ophir's gold was brought from Madagascar.[8][25] In 1946, Arthur Leib wrote that Malagasy practice of numerology is the product of Jewish influence on the people.[26] Also in 1946, Joseph Briant published L'hebreu à Madagascar, an influential comparative study of the Malagasy and Hebrew languages that purported to find substantial commonalities between the two.[27]

Lars Dahle wrote critically on the comparative arguments for the thesis in 1833: "The truth is, I think, that similarity of customs is nearly worthless as a sign of relationship, if not supported and borne out by other proofs of more importance".[8] The British explorer Samuel Copeland argued in 1847 that Malagasy people have "neither customs, traditions, rites, nor ceremonies sufficiently analogous to justify us in assigning their origin to that [Jewish] people."[28] In 1924, Chase Osborn protested at the Jewish thesis that "not one of the [Malagasy] tribes have the great Jewish nose which has followed that people during all time and is a sign of strength."[29]

Contemporary analyses of colonial European theories of Jewish Malagasy origin have noted that "the identification of Levitical customs was an obsession of the missionaries and early European anthropologists,"[10] and that "squaring the Bible's assertion of universality and shared descent from Noah's three sons with the realities of global diversity was [...] a central preoccupation of generations of ecclesiasts and Christian voyagers."[8] Eric T. Jennings argues that the discourses about Jewish roots in Madagascar led to the selection of the island by Nazi Germany for the Madagascar Plan, a proposed forcible relocation of Europe's Jews to Madagascar.[8]

Later investigations

[edit]No genetic testing has been done on specific Malagasy populations to corroborate claims of Jewish phylogenetic heritage. Genetic and linguistic studies that inquire broadly about Malagasy origins generally point to Austronesian settlement as the earliest human presence on the island, followed by waves of migration from other regions including East Africa.[10] A 2013 DNA study of the Antemoro people found two haplogroups linked to Middle Eastern origins in their parental lineages. Haplogroup J1 was found to connect the Antemoro with, among others, Portuguese Jews and people from Israel and Palestine. Haplogroup T1 connected the Antemoro to Israel, Spain, Lebanon, and Palestine.[30][31]

Nathan Devir judged the possibility of Malagasy racial descent from one of the Ten Lost Tribes to be "unlikely but possible" given the body of genetic research on Malagasy origins.[32] It has been alternatively proposed that Jews or their converted descendants may have been among the 10th-century Arab traders, or among the 15th-century sailors fleeing the Portuguese Inquisition, who came to Madagascar.[3][33][34] Edith Bruder writes that "the presence of Idumean colonies or Arab Jews from Yemen in Madagascar may be considered."[5] Tudor Parfitt, who describes 18th and 19th-century Merina royal tombstones with Hebrew writing, asserts that "There is good reason to believe that Portuguese anusim settled in Madagascar … There is no reason to doubt a historic connection with the Jews, but in the absence of any proof, it would be audacious to say there was a connection."[35]

Jewish communities in Madagascar

[edit]Zafy Ibrahim

[edit]17th century French colonial governor Étienne de Flacourt reported of a group called the Zafy Ibrahim, whom he'd encountered between 1644 and 1648 in the vicinity of the island of Nosy Boraha and judged to be of Jewish identity and descent.[36] The 500-600 people constituting the group were described in de Flacourt's account as being unfamiliar with Muhammad (considering his followers to be "lawless men"), celebrating and resting on Saturdays (unlike members of the island's Muslim population, who rested on Fridays), and bearing Hebrew names like Moses, Isaac, Jacob, Rachel and Noah.[18] The group collectively maintained a regional monopoly on religious animal sacrifice.[36] John Ogilby wrote in 1670 that the 600 "Zaffe-Hibrahim" inhabiting Nosy Boraha (which he called Nossi Hibrahim, 'Abraham's Isle') "will enter into no League with the Christians, yet trade with them, because it seems they have retain'd somewhat of the Ancient Judaism." He writes further that all the people from Plum Island to Antongil Bay call themselves Zaffe-Hibrahim and revere Noah, Abraham, Moses and David (and no other prophets).[37]

The Zafy Ibrahim have been theorized variously to be Yemenite Jews, Khajirites, Qarmatian Ismaili Gnostics, Coptic or Nestorian Christians, and descendants of pre-Islamic Arabs coming from Ethiopia.[36] In 1880, James Sibree published an account of the Zafy Ibrahim in Vohipeno, quoting one in affirmation: "we are altogether Jews".[36] An 1888 report described the Zafy Ibrahim's Hebraic rites and observances as "only a remote vibration of Judeo-Arabic influence."[38] By the French colonial period, Zafy Ibrahim began to identify themselves as Arabs and integrate into the Betsimisaraka people, and the people of Nosy Boraha today call themselves "Arabs".[36]

Colonial Period

[edit]

After France colonized the island and Europeans began settling there in the 19th century, a small number of Jewish families settled in Antananarivo, but did not establish a Jewish community.[39]

Madagascar was governed between August 1918 and July 1919 by a French-Jewish politician, Abraham Schrameck.[40][41][42]

On July 5, 1941, Madagascar, then under Vichy France's colonial rule, instituted a law mandating a census of all Jewish residents. Jews had to register and declare their wealth within a month of the law's enactment.[43] The census that year identified only 26 Jews, with half holding French nationality.[44] Despite this small population, Olivier Leroy, Madagascar's Pétainist Director of Education, conducted a public conference in 1942 in Antananarivo titled "Antisémitisme et Révolution nationale"—"Antisemitism and national revolution". The implementation of Vichy France's antisemitic laws in Madagascar led to the exclusion of the island's few Jews from various sectors, including the military, media, commerce, industry, and civil service.[44] These laws were strictly enforced. By August 15, 1941, those working in administrative roles were removed from their positions.[43] In one case, a civilian's letter to regional authorities identified Alexander Dreyfus, a rice merchant in Antanimena, as a Jew, and thus in breach of the law prohibiting Jews from trading in cereals or grains. The letter's author urged the administration to stop Dreyfus, lest the government seem "ridiculed by a common Jew". The regional leader in Tananarive ordered the police chief to see that Dreyfus "immediately cease his activities in the grain sector".[43]

In 2011, Adam Rovner found one Jewish grave on the island, belonging to Captain Israel Solomon Genussow. Genussow was a South African Jewish soldier for the British Army who grew up in Palestine and died in action on July 30, 1944, at the age of 28.[40][45] It was described in 2017 as the only known Jewish grave in Madagascar.[46]

A series of letters from a Jew in Madagascar to the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee were sent between 1947 and 1948, describing the conditions of Madagascar's Jews and requesting legal and financial assistance for the community.[47] The author writes in his first letter: "Since June 1940, when armistice was signed between France and Germany, all Jews in Madagascar were in troubles. Even our properties were taken by the government ruling the country at that time. We are not allowed to work as merchants, because we are Jews. In 1942, my brother had a big stock of rice, corn and manioc which was requisitioned by the government and since that time he never received any payment for those goods ... A few people here in [Antananarivo] who are Jews do not want to declare that they are so as they are afraid ... Consequently, the Jew Community here cannot have any meeting (official)."[48] He goes on in further letters to approximate the number of Jews in Madagascar as 1,200 including children, some of whom were born on the island.[49]

In 1950, a council of Haredi rabbis in Paris sought the guidance of the Chief Rabbi of Israel, Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog, regarding the permissibility of consuming zebu meat under Jewish dietary laws. Their inquiry was part of an effort to set up kosher slaughterhouses in Madagascar for the purpose of exporting meat to Israel. The inquiry generated a halakhic controversy among rabbinic authorities. Rabbi Herzog's positive stance was prominently challenged by Rabbi Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz. Ultimately, the Chief Rabbinate declined to approve the Malagasy meat, in deference to Rabbi Karelitz's argument.[50]

In 1955, the Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, leader of the Lubavitch-Chabad Hasidic Jewish movement, asked Rabbi Yosef Wineberg to go to Madagascar "in order to find any stray sheep of the House of Israel". At that time, the Jewish community in nearby South Africa was aware of only two Jews in Madagascar: a French doctor who did not identify with his Jewish heritage, and an Orthodox Tunisian Jew, Mr. Louzon, who had sent a telegram requesting conserved Kosher meats due to the lack of Kosher butchers in the region.[51] "I'm sure you'll find there more than one [Jew]," the Rebbe reportedly wrote in a letter to Rabbi Wineberg. Wineberg found and made contact with "about eight" Iraqi Jewish families in Madagascar. He affixed mezuzot to their doors, gave them a shofar, and taught them how to pray as a group.[52][53] The Rebbe maintained contact with Mr. Louzon and his wife.[54][51][55]

Communauté Juive de Madagascar

[edit]

The country is home to a small normative Jewish Malagasy population (in addition to a greater number of Jewish-identifying practitioners of syncretic combinations of Christianity, Judaism, Islam and traditional ancestor-worship and animism, including the 2,000 members of the "approximate[ly]... dozens"[10] of Messianic Jewish congregations in Madagascar, which syncretically incorporate Judaic elements into Christian belief).[56][57]

In 2011, according to a Malagasy news report, a group of Jiosy Gasy were evicted from a settlement under a bridge crossing the Ikopa River in Analamanga, under order of the Ministry of Land Management. Some Jiosy Gasy resisted, but they were beaten and forced by the military onto mini-buses going to Toliara, Toamasina, and Mahajanga.[58]

The community of "a couple hundred" Malagasy Jews in Ampanotokana arrived at rabbinic Judaism in 2010 as the result of three regional Messianic Jewish groups splintering off and studying the Torah.[59][60] In 2012, the community obtained state authorization to operate as a religious congregation, and in 2014 the group was recognized by the provincial office of the Ministry of the Interior and Decentralization, first under the Hebrew name Ôrah Vesimh’a ('Light and Joy'), and later as the formal Communauté Juive de Madagascar (Jewish Community of Madagascar).[61][56] The group refers to its ethnic division within Judaism as Madagascar Sepharad, praying in Sephardic-accented Hebrew and practicing a Sephardic-style liturgy, which they say was suggested to them by a Dutch Messianic Jew who thought Ashkenazi tradition would be inappropriate for such a decidedly non-European population.[62][61]

The community's president is Ashrey Dayves (born Andrianarisao Asarery), who leads alongside Petoela (Andre Jacque Rabisisoa), who serves as the Hebrew teacher, and Rabbi Moshe Yehouda. Yehouda is an Algerian Orthodox rabbi from Belgium who moved to Madagascar and became the group’s spiritual leader after their 2016 group conversion, marrying and having two children with one of the Jiosy Gasy. The three leaders have slightly different approaches, and there is infighting among the groups.[63] Touvya (Ferdinand Jean Andriatovomanana) is the community's chazzan.[59] Most of those in the administrative and spiritual leadership of the community are of a lower socioeconomic class relative to the general congregation. These leaders cite a lack of steady work as a reason for their wealth of free time that allows them to amass the knowledge necessary for their roles.[61]

Nathan Devir analyzes Malagasy Judaic adherence in context of the ancestor-honoring traditions of Madagascar's culture, writing that for Madagascar's new Jews, "the imperative to live Jewishly is a way to honour the ancestors more truly and efficiently." He also notes that Malagasy Jews reject the ancestor-venerating funerary practice of famadihana because it is effectively prohibited by Jewish burial custom. Though the dominant belief among Malagasy Jews is that Judaism is the same religion as their indigenous spirituality, there is no practical syncretism within the group.[61] William F. S. Miles observes anti-colonial sentiment in Malagasy Jewish identity, which is often characterized by a belief that the colonial French powers suppressed the truth of the Malagasy peoples' ancient Israelite and Jewish origins.[56] Marla Brettschneider, conversely, writes that men of the Antananarivo Jewish community deny the anti-colonial interpretation of Malagasy Judaism as a “Northern imposition”, while women of the community often refer to anti-colonialism in their religious narratives.[11]

Conversion and post-conversion activities

[edit]

In 2013, group members came in contact with a Jewish outreach group, who helped the community to organize a group Orthodox conversion.[64] Some members of this community were reportedly hesitant to convert to Orthodoxy because they understood themselves to already be ethnically Jewish.[3][65][32] Nathan Devir interpreted the Malagasy view of Judaism—which considers it an inherited parentage to be enacted through religious practice—as being "out of step" with the traditional notion of conversion. He reports that in 2013, some Malagasy Jews opposed to the prospect of conversion "[saw] their 'Jewish blood' as precluding the need for any formal conversion process."[66][67] Rabbi Moshe Yehouda, now the community’s spiritual leader, came to Madagascar after the conversion and established a Madagascar beit din to conduct conversions locally.[63]

In May 2016, after five years of self-study in Judaism, 121 members of the Malagasy Jewish community, including some children,[63] underwent conversion in accordance with traditional Jewish rituals; appearing before a beit din and submerged in a river mikvah. The men, all of whom were already circumcised, underwent the ritual of hatafat dam brit.[63] Because the local Parks Department denied the Communauté's request to build a temporary structure on the Ikopa River in which to disrobe (with mikvah baths traditionally requiring complete nudity), the ritual occurred at a river far from town, and the converts built a tent from tarp and wood to protect their privacy.[68][69] The conversion, presided over by three Orthodox rabbis, was followed by fourteen weddings and vow renewals under a makeshift chuppah at a hotel in Antananarivo.[70][34]

According to a 2016 State Department report on religious freedom in Madagascar, members of the Communauté Juive de Madagascar reported antisemitic discrimination following their conversion: some private schools refused to register Jewish children after learning of their religious affiliation, and one landlord cancelled a lease contract after learning that the rental house was going to be used as a Jewish religious school. Members of the community also reported "unwelcome attention" and comments for their religious attire.[71] The following year, after "multiple public interactions with the leaders of other religious groups that served as examples for the public", a leader of the Communauté Juive de Madagascar reported an improvement in attitudes toward the community, with local communities no longer critical of their religious dress and Jewish children no longer being denied private school enrollment.[72]

In 2018, 11 more members of the Ampanotokana Jewish community underwent Orthodox conversion, presided over by a Belgian-Malagasy rabbi.[73] In November 2019, the group formed a Vaad (rabbinical council) to handle and publish guidance of halakha (Jewish law).[74] In 2021, the Communauté Juive de Madagascar opened a printing shop to generate income for the community and print Jewish texts.[75][76] The effort was led by Rabbi Moshe Yehouda.[63]

"Recently" as of 2023, the Mayor of Antananarivo Naina Andriantsitohaina offered the community land to open a new synagogue near the former Queen’s palace, "in the most prominent location in Antananarivo".[63]

Aaronites

[edit]

William F.S. Miles documents various Malagasy religious communities claiming Jewish lineage, including a robe-wearing, animal-sacrificing "Aaronite" sect in their village of Mananzara, who assert that their Jewish ancestors, among whom they count Aaron, brother of Moses, were swept to Madagascar in the deluge of Genesis. Mananzara's Aaronite community is organized with priests (analogous to kohenim) and their assistants (analogous to Levites) officiating to the community.[77] The Jewish identity of Mananzara villagers is also expressed in the logo of their elected leader Roger Randrianomanana, which features a six-pointed Star of David alongside a Malagasy valiha (which many Malagasy claim are inherited from King David).[3][10]

Nathan Devir describes Merina traditionalist groups, among them the Temple of Loharanom-Pitahiana (meaning 'the Source of the Blessing') of Ambohimiadana, who are identified with rabbinic and Messianic Jewish communities on the island but do not feel a need to align their own religion, which they prefer to call "Hebraic religion" or "Aaronism", with the norms of rabbinic Judaism, which they regard as a later and somewhat strayed derivation from the ancient Israelite creed inherited by the Merina. While many Malagasy claim such treasures as the Ark of the Covenant, fragments of the Tablets of Stone, and Moses' staff to be kept in Vatumasina, though the kings and scribes maintain that the Hebrew treasures were lost in a fire during the French repression of the Malagasy Uprising of 1947.[33] The narrative account of their origin was related to Devir as follows:

Before the Babylonian invasion that destroyed the Temple of Solomon, our priestly and Levite ancestors had received prophetic messages that foresaw this devastation. They were instructed to leave Jerusalem and to take with them the sacred objects held in the holy of Holies [...] They left Jerusalem before the disaster and arrived on the eastern coast of Madagascar in 1305, having passed by India, Vietnam, Indonesia [Java], and the Indian Ocean (a sea voyage guided by the winds and the tides).

According to local priests, the leaders of Ambohimiadana did not write down their oral histories and ancestral codes until 1977. Some of these writings are said to be in Hebrew, but Devir was unable to verify this. The Merina Loharanom-Pitahiana traditionalists reject the Talmud, Kabbalah, and other post-biblical texts, and have "politely declined" invitations to integrate into the Communauté Juive de Madagascar.[3][10]

Miles also documents a group of contemporary Antemoro "kings and scribes" in Vatumasina, who claim descendance from an Arabized Jewish figure named Ali Ben Forah, or Alitawarat (Ali of the Torah), who came to Madagascar from Mecca in the 15th century.[79][3][78]

Other Jews and Judaic groups

[edit]The Église du Judaïsme Hébraïque is a charismatic cult in Madagascar led by the Judaic mystic Rivo Lala (also called "Kohen Rivolala"), whose teachings circulate via the internet.[3] Nathan Devir describes Lala's religion as "a mélange of spiritualism, Catholicism, and theosophy with a healthy dose of Aaronite-descent propaganda and a cultlike emphasis on his own supernatural abilities." Lala's followers are described as wearing kippot and flowing tunics similar to Arabian thawbs.[10] In 2012, Lala publicly claimed that he could guarantee a return to acceptance and power for the then-exiled former President of Madagascar Marc Ravalomanana "if he accepts me as [his] rabbi and agrees to follow the religion of Hebraic Judaism".[10][80] Lala has been arrested several times, and in November 2015 was arrested in Miandrivazo for "witchcraft against around fifty high school girls" after authorities alleged to have found found wooden idols in his car.[81][10] His arrest incited a frenzy in the town, with the families of the allegedly possessed girls demanding that Lala be handed over to them.[82] He was sentenced to one year in prison for witchcraft in January 2016, and was acquitted in June of that year.[83][84]

Since 2004, a Malagasy organization called Trano koltoraly malagasy has advocated for a Jewish origin and identity among Malagasy people, proposing origins among the Israelites of the Exodus. The group observes a "Malagasy new year" at the end of March or beginning of April.[12]

Foreign affairs

[edit]The Madagascar Plan

[edit]

In the summer of 1940, following various similar proposals made by Jews and anti-semites alike since the late 19th century, Nazi Germany proposed the Madagascar Plan, according to which 4 million European Jews would be expelled and forcibly relocated to the island. Eric T. Jennings has argued that the plan's persistence, from its earliest public proposals to its explorations by the French, Polish, and German governments during World War II, stems from the "Jewish thesis" discourse regarding Madagascar's supposed ancient Jewish roots.[8]: 174 In 1937, Bealanana and Ankaizinana, two very remote areas with high elevations and low population densities, were identified by a French "expert" delegation of three men, two of whom were Jews, as a possible site for Jewish relocation.[40][8]

Léon Cayla, the colonial Governor-General of Madagascar from May 1930 to April 1939, was a strong opponent of the Polish proposal, arguing persistently against Jewish immigration to the island, and ignoring and rebuffing repeated appeals from various Jewish organizations to allow for the mass resettlement and immigration of Polish Jews to Madagascar.[8]: 191–193 The reaction in the tightly-censored Malagasy press reflected this opposition, expressing concern that the relocated Jews "would not remain engaged in agriculture for long but would move into trading or compete with the locals for the remaining jobs" and would receive favorable treatment and assistance from the Colonial Minister over the indigenous Malagasy and long-established French settlers on the island. It was "unanimously lamented" that Madagascar was willing to spend money on the internment of Spanish refugees in France and the resettlement of Polish Jews, but did nothing for its colonies.[85] Two antisemitic letters to Cayla from Malagasy artillerymen stationed in Syria, both expressing opposition and concern at the prospect of Jewish settlement of the island, were apparently marked by Cayla for inclusion in a collection of negative reactions to potential Jewish immigration, to be shown to his superiors in Paris.[8]: 199

The plan, which relied on the French colony of Madagascar being handed over to Germany, was shelved after the British capture of Madagascar from Vichy in 1942. It was permanently abandoned with the commencement of the Final Solution, the policy of systematic genocide of Jews.[86][8]

Relations with Israel

[edit]When Madagascar gained independence as the Malagasy Republic in 1960, Israel was one of the first countries to recognize its independence, send an ambassador, and establish an embassy on the island. President Philibert Tsiranana of Madagascar and President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi of Israel each visited the other’s country during their overlapping terms. Bilateral relations were suspended after the Yom Kippur War in 1973.[87][39] In 1992, after visiting Israel at the invitations of Mashav and Histadrut, Malagasy politician Raherimasoandro "Hery" Andriamamonjy founded Club Shalom Madagascar, an organization liaising diplomatic, cultural, and commercial relations between the two countries.[79] Bilateral relations were restored in 1994.[39] In 2005, a diplomat from the African department of the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs reached out to Andriamamonjy in order to inquire about Madagascar's Jews and build a database on the then-150-strong community of Jiosy Gasy. One of her inquiries related to the question of whether the island had a Jewish cemetery.[88]

In 2017, The Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the South African branch of Israel's national emergency service, Magen David Adom, sent aid to Madagascar amidst a serious outbreak of the plague.[89][90] In 2020, Madagascar formed a parliamentary Israel Allies Caucus, chaired by Retsanga Tovondray Brillant de l’Or, as part of the Israel Allies Foundation.[91]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2018 Report on International Religious Freedom: Madagascar". 2019.

- ^ Devir, Nathan (2018). "Propagating Modern Jewish Identity in Madagascar: A Contextual Analysis of One Community's Discursive Strategies". Connected Jews: Expressions of Community in Analogue and Digital Culture. Liverpool University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1198t80. ISBN 978-1-906764-86-9. JSTOR j.ctv1198t80. S2CID 239843895.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Miles, William F.S. (December 2017). "Malagasy Judaism: The 'who is a Jew?' conundrum comes to Madagascar". Anthropology Today. 33 (6): 7–10. doi:10.1111/1467-8322.12391. ISSN 0268-540X.

- ^ Devir, Natan. "Origins and Motivations of Madagascar's Normative Jewish Movement." Becoming Jewish (2016): 49

- ^ a b c d e Bruder, Edith (2013). "Descendants of David". In Sicher, Efraim (ed.). Race, color, identity: rethinking discourses about "Jews" in the twenty-first century. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0-85745-892-6.

- ^ a b Bruder, Edith (2013-05-01), "Chapter 10. The Descendants of David of Madagascar: Crypto-Judaism in Twentieth-Century Africa", Race, Color, Identity, Berghahn Books, pp. 196–214, doi:10.1515/9780857458933-013, ISBN 978-0-85745-893-3, retrieved 2024-01-10

- ^ Parfitt, Tudor (2002) The Lost Tribes of Israel: the History of a Myth. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson p.203.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Jennings, Eric T. (2017). Perspectives on French Colonial Madagascar. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-55967-8. ISBN 978-1-137-59690-1.

- ^ a b c d Devir, Nathan P. (2018-12-14). "Popular Perceptions of Israelite Genealogy in Madagascar". In Bruder, Edith (ed.). Africana Jewish Journeys: Studies in African Judaism. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-2345-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Devir, Nathan P. (2022-02-28), "First-Century Christians in Twenty-First Century Africa: Between Law and Grace in Gabon and Madagascar", First-Century Christians in Twenty-First Century Africa, Brill, doi:10.1163/9789004507708, ISBN 978-90-04-50770-8, S2CID 239810675, retrieved 2024-01-10

- ^ a b Brettschneider, Marla (2018-12-14). "5. Anti-Colonialism and Jewish Women in Madagascar". In Bruder, Edith (ed.). Africana Jewish Journeys: Studies in African Judaism. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-2345-6.

- ^ a b Domenichini, Jean-Pierre. "LE PEUPLEMENT DE MADAGASCAR Des migrations et origines mythiques aux réalités de l'histoire". Madagascar Environmental Justice Network.

- ^ Goedefroit, Sophie; Roca, Albert (2022-06-20). "La "plus belle énigme du monde" ne veut pas être résolue. Le besoin de mémoire multiple à Madagascar". Quaderns de l'Institut Català d'Antropologia. 37 (2): 383–406. doi:10.56247/qua.371. ISSN 2385-4472.

- ^ "Sensationnelle découverte d'inscriptions rupestres," Tana Journal July 17, 1953.

- ^ Vérin, Pierre (1962). "Rétrospective et Problèmes de l'Archéologie à Madagascar". Asian Perspectives. 6 (1/2): 198–218. ISSN 0066-8435. JSTOR 42928938.

- ^ a b maitso (2010-05-12). "Le "rocher qui parle" à Alakamisy-Ambohimaha Fianarantsoa MADAGASCAR". Mystères et conspirations (in French). Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ Faces Of Africa: The Jews of Madagascar, retrieved 2024-01-13

- ^ a b Ferrand, Gabriel (1905). "Les Migrations Musulmanes Et Juives a Madagascar". Revue de l'histoire des religions. 52: 381–417. ISSN 0035-1423. JSTOR 23661459.

- ^ Goedefroit, Sophie; Roca, Albert (2021). "La "plus belle énigme du monde" ne veut pas être résolue. Le besoin de mémoire multiple à Madagascar". Quaderns de l'Institut Català d'Antropologia (in French). 37 (2): 383–406. doi:10.56247/qua.371. ISSN 2385-4472.

- ^ Jakka, Sarath Chandra (September 2018). Fictive Possessions: English Utopian Writing and the Colonial Promotion of Madagascar as the "Greatest Island in the World" (1640 - 1668) (PDF) (phd thesis). University of Kent, University of Porto.

- ^ Drury, Robert (1729). "Introduction". In Mackett, William (ed.). Madagascar: Or, Robert Drury's Journal, During Fifteen Years Captivity on that Island (1st ed.). London: W. Meadows.

- ^ Copland, Samuel (2009-09-24). A History Of The Island Of Madagascar: Comprising A Political Account Of The Island, The Religion, Manners, And Customs Of Its Inhabitants. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-120-25217-3.

- ^ "Jews and Madagascar". premium.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ Grandidier, Histoire, vol. 4, part 1, 96–103

- ^ "The Gold of Ophir: Whence Brought and by Whom?". Nature. 65 (1690): 460–461. March 1902. doi:10.1038/065460a0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 13251803.

- ^ Leib, Arthur (1946). "Malagasy Numerology". Folklore. 57 (3): 133–139. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1946.9717825. ISSN 0015-587X. JSTOR 1257737.

- ^ Parfitt, Tudor; Trevisan-Semi, Emanuela (2005). "The Construction of Jewish Identities in Africa". The jews of Ethiopia: the birth of an elite. Routledge jewish studies series. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-31838-9.

- ^ Samuel Copeland, A History of the Island of Madagascar, Comprising a Political Account of the Island, the Religion, Manners, and Customs of Its Inhabitants, and Its Natural Productions (London: Burton and Smith, 1822), 56

- ^ Osborn, Chase Salmon (1924). Madagascar, Land of the Man-eating Tree. Republic Publishing Company. pp. 44–45.

- ^ Capredon, Mélanie (2011-11-25). Histoire biologique d'une population du sud-est malgache : les Antemoro (phdthesis thesis) (in French). Université de la Réunion.

- ^ Capredon, Mélanie; Brucato, Nicolas; Tonasso, Laure; Choesmel-Cadamuro, Valérie; Ricaut, François-Xavier; Razafindrazaka, Harilanto; Rakotondrabe, Andriamihaja Bakomalala; Ratolojanahary, Mamisoa Adelta; Randriamarolaza, Louis-Paul; Champion, Bernard; Dugoujon, Jean-Michel (2013-11-22). "Tracing Arab-Islamic Inheritance in Madagascar: Study of the Y-chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA in the Antemoro". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e80932. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...880932C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080932. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3838347. PMID 24278350.

- ^ a b Dolsten, Josefin (7 December 2016). "In Madagascar, 'world's newest Jewish community' seeks roots". The Times of Israel.

- ^ a b "The secrets of the Malagasy Jews of Madagascar". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 2015-09-26. Retrieved 2024-01-10.

- ^ a b Josefson, Deborah (5 June 2016). "In remote Madagascar, a new community chooses to be Jewish". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Berkowitz, Adam Eliyahu (2016-05-30). "Mysterious Madagascar Community Practicing Jewish Rituals Officially Enters Covenant of Abraham [PHOTOS]". Israel365 News. Retrieved 2024-01-18.

- ^ a b c d e Graeber, David (2023-01-24). Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-374-61020-3.

- ^ "Africa being an accurate description of the regions of Ægypt, Barbary, Lybia, and Billedulgerid, the land of Negroes, Guinee, Æthiopia and the Abyssines : with all the adjacent islands, either in the Mediterranean, Atlantick, Southern or Oriental Sea, belonging thereunto : with the several denominations fo their coasts, harbors, creeks, rivers, lakes, cities, towns, castles, and villages, their customs, modes and manners, languages, religions and inexhaustible treasure : with their governments and policy, variety of trade and barter : and also of their wonderful plants, beasts, birds and serpents : collected and translated from most authentick authors and augmented with later observations : illustrated with notes and adorn'd with peculiar maps and proper sculptures / by John Ogilby, Esq. ..." In the digital collection Early English Books Online 2. https://name.umdl.umich.edu/A70735.0001.001. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Accessed June 2, 2024.

- ^ "PASEUDO-JEWS". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 15, 682. New South Wales, Australia. 28 June 1888. p. 11. Retrieved 10 January 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c Skolnik, Fred (2006). "Madagascar". Encyclopedia Judaica. Vol. 13. Detroit: Macmillan Reference. p. 330.

- ^ a b c Rovner, Adam L. (2020-05-28). "The Lost Jewish Continent". In the Shadow of Zion. New York University Press. doi:10.18574/nyu/9781479804573.001.0001. ISBN 978-1-4798-0457-3. S2CID 250109046.

- ^ Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael (2007). Encyclopaedia judaica (2nd ed.). Detroit (Mich.): Thomson Gale. ISBN 978-0-02-865929-9.

- ^ Graça, J. Da; Graça, John Da (2017-02-13). "Madagascar". Heads of State and Government. Springer. p. 546. ISBN 978-1-349-65771-1.

- ^ a b c Jennings, Eric Thomas (2001). Vichy in the tropics: Petain's national revolution in Madagascar, Guadeloupe, and Indochina, 1940-1944. Stanford (Calif.): Stanford university press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4179-8.

- ^ a b Jennings, Éric T.; Verney, Sébastien (2009-03-01). "Vichy aux Colonies. L'exportation des statuts des Juifs dans l'Empire". Archives Juives. 41 (1): 108–119. doi:10.3917/aj.411.0108. ISSN 0003-9837.

- ^ Rovner, Adam (2011-11-02). "Madagascar: An Almost Jewish Homeland - Page 4 of 5". Moment Magazine. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ Greenspan, Ari; Zivotofsky, Ari (February 2017). "The Jews of Madagascar: Jewish Core in Island Lore" (PDF). Mishpacha. pp. 69–77.

- ^ Madagascar: Tananarive - Jews of Madagascar 1947-1948, retrieved 2024-01-17

- ^ Goldstein, Melvin S. (5 December 1947), Letter from Melvin S. Goldstein to American Jewish Committee, retrieved 2024-01-19

- ^ Mussard, Lionel (3 February 1948), Letter to Dr. Joel D. Wolfsohn, retrieved 2024-01-19

- ^ Bleich, J. David (2005-01-01). "IX. Kashrut". Contemporary Halakhic Problems, Vol. 5. Southfield, MI: Targum/ Feldheim. ISBN 978-1-56871-353-3.

- ^ a b Rabinowitz, Louis Isaac (29 August 2023). "Where There Are No Jews". No Small Jew: Stories of the Lubavitcher Rebbe and the Infinite Value of the Individual. Hasidic Archives. pp. 32–39.

- ^ Zaklikowski, Dovid (June 27, 2012). ""Globetrotting Ambassador" Fueled Jewish Life in the Farthest Reaches of the Globe". Chabad.

- ^ Wineberg, Yosef. ""There Are No Jews in Madagascar"". Chabad.

- ^ Wineberg, Yosef (29 August 2023). "Responsibility for Your Corner". No Small Jew: Stories of the Lubavitcher Rebbe and the Infinite Value of the Individual. Hasidic Archives. pp. 40–45.

- ^ Schneerson, Menachem (Fall 1961). "A Jew in Madagascar". Chabad.

- ^ a b c Miles, William F.S. (December 2017). "Malagasy Judaism: The 'who is a Jew?' conundrum comes to Madagascar". Anthropology Today. 33 (6): 7–10. doi:10.1111/1467-8322.12391. ISSN 0268-540X.

- ^ Kestenbaum, Sam. "'Joining Fabric of World Jewish Community,' 100 Convert on African Island of Madagascar". The Forward. Retrieved 2018-09-26.

- ^ Maxime, Rakoto (26 May 2011). "Jiosy Gasy Voaroaka omaly teo amin'ny By-Pass". www.tiatanindrazana.mg. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ a b Josefson, Deborah (5 June 2016). "In remote Madagascar, a new community chooses to be Jewish". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ "The secrets of the Malagasy Jews of Madagascar". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 2015-09-26. Retrieved 2024-01-10.

- ^ a b c d Devir, Nathan P. (2022-02-28), "First-Century Christians in Twenty-First Century Africa: Between Law and Grace in Gabon and Madagascar", First-Century Christians in Twenty-First Century Africa, Brill, doi:10.1163/9789004507708, ISBN 978-90-04-50770-8, S2CID 239810675, retrieved 2024-01-10

- ^ Sussman, Bonita (September 2016). "International Conference on Bnei Anousim: Address by Bonita Nathan Sussman" (PDF). p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e f Brettschneider, Marla (2023). "Madagascar". In Brettschneider, Marla; Sussman, Bonita Nathan (eds.). Jewish Africans describe their lives: evidence of an unrecognized indigenous people: Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe. Lewiston, New York: The Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-1-4955-1067-0.

- ^ Kestenbaum, Sam. "'Joining Fabric of World Jewish Community,' 100 Convert on African Island of Madagascar". The Forward. Retrieved 2018-09-26.

- ^ US State Dept 2022 report

- ^ Devir, Nathan (2016). "Origins and Motivations of Madagascar's Normative Jewish Movement". In Parfitt, Tudor; Fisher, Netanʾel (eds.). Becoming Jewish: new Jews and emerging Jewish communities in a globalised world. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 49–63. ISBN 978-1-4438-9965-9.

- ^ Josefson, Deborah (2016-06-05). "In remote Madagascar, a new community chooses to be Jewish". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 2024-01-18.

- ^ "The Other Side of the World: My Journey to Jewish Madagascar". www.brandeis.edu. Retrieved 2024-01-18.

- ^ Hayyim, Mayyim (2016-07-20). "Mikveh Moments in Madagascar: Immersion and Conversion on the Other Side of the World". Mayyim Hayyim. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ Vinick, Barbara (September 2022). "Jewish Weddings Around the World" (PDF). Kulanu.

- ^ "Madagascar". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ United States Department of State (2018). "2017 Report on International Religious Freedom: Madagascar". United States Department of State.

- ^ Page, Posted In Home; Uncategorized (2018-12-03). "Madagascar Community Members Convert to Judaism". Kulanu. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ "Madagascar Jewish Community Forms Vaad" (PDF). Kulanu. Fall 2019.

- ^ "Mini-Grants Update" (PDF). Kulanu. Winter 2021. p. 15.

- ^ Kulanu Year End Celebration | Kulanu, Inc was live. | By Kulanu, Inc | Facebook, retrieved 2024-01-14

- ^ Miles, William F. S. (2019-01-02). "Who Is a Jew (in Africa)? Definitional and Ethical Considerations in the Study of Sub-Saharan Jewry and Judaism". The Journal of the Middle East and Africa. 10 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/21520844.2019.1565199. ISSN 2152-0844.

- ^ a b "Fombandrazana Antemoro. Fandroana Andriaka". moov.mg (in French). Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ a b Weisfield, Cynthia. "Madagascar Groups Seek Closer Jewish Ties". Kulanu. Retrieved 2024-01-10.

- ^ "Kohen Rivo Lala : " Je peux faire revenir Marc Ravalomanana si… " : TANANEWS". 2012-04-24. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2024-02-05.

- ^ "Sorcellerie présumée : le Kohen Rivolala écroué - NewsMada". 28 November 2015. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 2024-02-05.

- ^ "Madagascar : arrestation d'un gourou soupçonné d'avoir jeté des mauvais sorts". lexpress.mu (in French). 2015-11-28. Retrieved 2024-02-05.

- ^ Andriamarohasina, Seth (22 January 2016). "Madagascar: Sorcellerie - Le Kohen Rivolala condamné à un an ferme". L'Express de Madagascar.

- ^ Andriamarohasina, Seth (9 June 2016). "Sorcellerie - Kohen Rivolala acquitté". L'Express de Madagascar.

- ^ Brechtken, Magnus (1998-06-10). "Madagaskar für die Juden": Antisemitische Idee und politische Praxis 1885–1945 (in German) (2nd ed.). München: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-486-56384-9.

- ^ Browning, Christopher R. (1998). The path to Genocide: essays on launching the final solution (Reprint ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55878-5.

- ^ Oded, Arye (2010). "Africa in Israeli Foreign Policy—Expectations and Disenchantment: Historical and Diplomatic Aspects". Israel Studies. 15 (3): 121–142. doi:10.2979/isr.2010.15.3.121. ISSN 1084-9513. JSTOR 10.2979/isr.2010.15.3.121. S2CID 143846951.

- ^ "MADAGASCAR : Israel interested in Madagascan jews - 23/07/2005 - The Indian Ocean Newsletter". Africa Intelligence. 2024-06-10. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "Israel rushes emergency aid to Madagascar, Black Death casualties rise". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 2017-11-08. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ^ Blackburn, Nicky (2017-11-07). "Israel sends emergency aid package to plague-stricken Madagascar". ISRAEL21c. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ^ "Madagascar initiates Parliamentary Israel Allies Caucus". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 2020-09-07. Retrieved 2024-01-17.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Often referred to in French as le rocher qui parle ('the boulder that speaks') or le rocher sacré ('the sacred boulder')

External links

[edit]- Jewish Virtual Library website

- Jewish Photo Library images from Madagascar

- Faces of Africa: The Jews of Madagascar — Documentary short by CGTN Africa

- Journey to Judaism — Documentary short about the conversion of the Malagasy Sepharad Jews