Ghevont Alishan

Ghevont Alishan | |

|---|---|

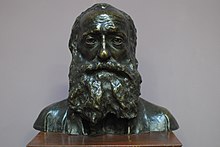

Portrait of Alishan from his 1901 book Hayapatum (Armenian history) | |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 6, 1820 |

| Died | November 9, 1901 (aged 81) Venice, Kingdom of Italy |

| Denomination | Armenian Catholic |

| Residence | San Lazzaro degli Armeni |

Ghevont Alishan[a] (Armenian: Ղեւոնդ Ալիշան; July 18 [O.S. July 6], 1820 – November 22 [O.S. November 9], 1901) was an Armenian Catholic priest, historian, educator and poet. He was a prolific author throughout his long career and gained recognition from Armenians and European academic circles for his contributions to Armenian literature and scholarship.

Born to an Armenian Catholic family in Constantinople, he received his education at the academy of the Armenian Catholic Mekhitarist Congregation on Saint Lazarus Island in Venice and joined the order in 1840. Between 1840 and 1872, he held a number of teaching and administrative positions in his order's educational institutions in Venice and Paris. During this period, he gained renown as a poet, writing mainly in Classical Armenian on both patriotic and religious themes. He is regarded as one of the first Armenian Romantic poets.

After 1872, Alishan devoted himself completely to his scholarly work. He notably wrote a number of long works on the historical provinces of Armenia and prepared for publication many old Armenian texts. Most of his works are in Armenian, but he also wrote in, and was translated into, French, English and Italian.

Biography

[edit]Alishan, born Kerovpe Alishanian, was born on July 18 [O.S. July 6], 1820, in Constantinople, to numismatist and archaeologist Bedros-Markar Alishanian.[1] His family was Armenian Catholic.[2] After receiving his primary education at the local Chalikhian School (1830–1832), he continued his studies at the Mekhitarist school in Venice (1832–1841). He became a member of the order in 1838[1] or 1840 and was ordained as a priest.[2][3] From 1841 to 1850, he worked as a teacher and, from 1848, principal at the Raphael College (the Mekhitarist-run Armenian boarding school) in Venice. From 1849 to 1851, he was the editor of the Mekhitarists' scholarly journal Bazmavep. From 1852 to 1853, he toured Europe, traveling to England, Austria, Germany, France, Belgium and Italy.[2] From 1859 to 1861, he was a teacher and principal at another Mekhitarist-run school, the Samuel-Moorat school in Paris. He again worked at the Raphael College in 1866–1872. In 1870, he became the acting head of the Mekhitarist Congregation. After 1872, he completely devoted himself to his scholarly activities.[1]

In his later years, Alishan was honored by a number of European academic institutions.[2] He was a laureate of the Legion of Honor of the French Academy (1886), an honorary member and doctor of the Philosophical Academy of Jena, an honorary member of the Asian Society of Italy, the Archeological Society of Moscow, the Venice Academy and the Archeological Society of Saint-Petersburg.[1] He died on November 22 [O.S. November 9], 1901, and was buried on Saint Lazarus Island in Venice.[4]

Literary activities

[edit]Alishan was a prolific author who wrote across different genres over the course of his more than sixty-year-long career․[5][6] He began his literary career in 1843, publishing works in prose and verse and scholarly articles in Bazmavep.[1] He initially gained renown for his poems, first published in Bazmavep and later compiled in a series of volumes titled Nvagk (Songs), and for his Hushikk hayreneats hayots (Memories of the Armenian homeland), a collection of episodes from Armenian history in vernacular prose. He also translated a number of works by European authors into Armenian.[6]

Poetry

[edit]Alishan wrote poems mainly in Classical Armenian on both patriotic and religious themes. Many of his poems were published in a five-volume series titled Nvagk (1857–58). The first volume, Mankuni, contains prayers and religious poems for children. The third volume, Hayruni, consists of patriotic poems, including the cycle of poems in vernacular Armenian subtitled "Ergk Nahapeti" ('Songs of the patriarch', after the pen name he signed these poems with, Nahapet), which is traditionally regarded as Alishan's greatest poetic achievement. The fourth volume, Teruni, consists of religious poems. The fifth volume, Tkhruni, contains poems on human suffering, death, and exile. Alishan gave up poetry in his early thirties, announcing his departure from the genre with the poem "Husk ban ar Vogin nvagahann" (A final word to the singing Spirit).[7]

Alishan was one of the first Armenian poets to write in the Romantic style. His patriotic poems emphasize the concept of homeland, its natural beauty, and heroic episodes in Armenian history. One of his poems was later set to music by the Venetian violinist Pietro Bianchini and given the title "Bam porotan" (Boom, they roar). After the Armenian genocide, it became a sort of anthem for the Armenian diaspora.[2] Mekhitarist authors and some other critics have rated Alishan's Classical Armenian poems, with their Classical style and subject matter, most highly while valuing the more vernacular "Ergk Nahapeti" less. Alishan himself considered Classical Armenian to be superior to the vernacular language. Most Soviet Armenian authors, on the other hand, celebrated the "Ergk Nahapeti" over the rest of Alishan's poems.[8]

Translations into Armenian

[edit]Alishan translated works in prose and verse from English, French, Persian and Italian into Armenian.[5] His translations include Canto IV of Lord Byron's Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, Friedrich Schiller's "Die Glocke,"[6] and works by François de Malherbe, Alphonse de Lamartine, and François-René de Chateaubriand.[5] He also published a collection of translations from American poets including N. P. Willis, Andrews Norton, William Cullen Bryant, and J. G. Whittier under the title Knar amerikean (American lyre).[6]

Scholarly works

[edit]

Alishan planned to complete 20–22 large volumes on the provinces and districts of historical Armenia, but published only four: Shirak (1881), Sisuan (1885), Ayrarat (1890) and Sisakan (1893).[1] These long works contain information about the history, geography, topography, customs and plant life of those regions.[2][9] Some of his uncompleted geographical studies have remained in manuscript form.[10] In 1988–91, Bazmavep published Alishan's hitherto unpublished studies of the provinces of Artsakh and Utik;[11][12] the former was also published as a separate book in Yerevan in 1993.[13]

Most of Alishan's works are in Armenian, but he also wrote in, and was translated into, French, English and Italian. These include a collection of Armenian folk songs translated into English (1852), a collection of primary sources in Italian regarding Armeno-Venetian relations in the medieval period (L'Armeno-Veneto, 1893), and several French adaptations of his Armenian studies, such as Étude de la patrie: Physiographie de l’Armenie (1861), Schirac, canton d’Ararat (1881), and Sissouan, ou l’Arméno-Cilicie: description géographique et historique (1899). Publishing in European languages made Alishan's work more accessible and earned him the admiration of several European academics; later in his life, he received several honors from European academic institutions (see above). In 1895, Alishan published Hay-Busak, a dictionary of the flora of Armenia, and Hin Havatk kam hetanosakan kronk hayots (The old faith or the pagan religion of the Armenians), a study of pre-Christian Armenian religion.[2] In 1901, he published Hayapatum (Armenian history). The first part of this work is dedicated to the history of Armenian history-writing, while the second part presents 400 excerpts from the works of Armenian historians regarding Armenian history up until the 17th century.[1]

Alishan prepared many old Armenian texts for publication.[9] In the series Soperk haykakank, he brought to light a number of short, simpler texts of pre-modern Armenian literature, which contributed to the study of the early history of Armenian learning and the Armenian Church.[1]

Views

[edit]Alishan’s religious worldview greatly influenced his scholarly and literary work.[1][7] According to Bardakjian, "Any search [in Alishan's work] for dissension from Christian tenets on the Creator, the Creation, and human behavior would be a futile attempt."[7] Alishan rooted his understanding of Armenian history in the biblical narrative of Genesis and tried to prove the traditional view that the Garden of Eden was located in Armenia using data from modern science. He saw patriotism and faith as inseparable, writing at the end of his Hushikk hayreneats hayots: "One who is true to God and himself is true to his homeland. He who is untrue to his homeland is true neither to his soul nor to heaven."[1] Bardakjian describes Alishan's patriotism as "a cultural and in many ways a passive patriotism," one which nonetheless had a major impact on the Armenian reading public and its growing national consciousness. He suggests that the "boisterous tone" in some of Alishan's poems may "replace, or cover up, rebellious sentiments unutterable by a monk."[8]

Legacy

[edit]Alishan's literary and scholarly work was highly regarded by many of his contemporaries and later intellectuals. Since most of Alishan's poetry is written in Classical Armenian, it has remained largely inaccessible to much of the Armenian reading public. According to Bardakjian, it was Alishan's Romantic poetry in Modern Armenian that secured him a lasting place in Armenian literary history. Alishan had some influence in the stylistic and thematic choices of later authors.[8]

Armenian flag

[edit]In 1885 Alishan created the first modern Armenian flag. His first design was a horizontal tricolor, but with a set of colors different from those used on the Armenian flag of today. The top band would be red to symbolize the first Sunday of Easter (called "Red" Sunday), the green to represent the "Green" Sunday of Easter, and finally an arbitrary color, white, was chosen to complete the combination. While in France, Alishan also designed a second flag inspired by the national flag of France. Its colors were red, green, and blue, representing the band of colors that Noah saw after landing on Mount Ararat.[citation needed]

Selected publications

[edit]- Armenian popular Songs: translated into English by the R. Leo M. Alishan DD. of the Mechitaristic Society, Venice, S. Lazarus, 1852.

- Etude de la patrie: physiographie de l'Arménie: discours prononcé le 12 août 1861 à la distribution annuelle des prix au collège arménien Samuel Moorat, Venise, S. Lazar, 1861.

- «Յուշիկք հայրենեաց հայոց» (Memories of the Armenian Homeland) 1869.

- «Շնորհալի եւ պարագայ իւր» ('Shnorhali ew paragay iwr', Armenian History). 1873, Venice.

- «Շիրակ» (Shirak) 1881.

- Deux descriptions arméniennes des lieux Saints de Palestine, Gènes, 1883.

- «Սիսուան» (Sisouan) 1885.

- «Այրարատ» (Ayrarat) 1890.

- «Սիսական» (Sisakan) 1893.

- «Հայապատում» ('Hayapatum', Armenian History). 1901, Venice.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Devrikyan, Vardan (2002). "Alishan Ghevond". In Ayvazyan, Hovhannes (ed.). Kʻristonya Hayastan hanragitaran [Christian Armenia encyclopedia] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia Publishing House. pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c d e f g Manoukian, Jennifer (2022). Leerssen, Joep (ed.). "Alishan, Ghevont". Encyclopedia of Romantic Nationalism in Europe. Study Platform on Interlocking Nationalisms. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ Bardakjian, Kevork B. (2000). A Reference Guide to Modern Armenian Literature 1500-1920. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 273. ISBN 0-8143-2747-8.

- ^ Muradyan, Samvel (2021). Hay nor grakanutʻyan patmutʻyun: Usumnakan dzeṛnark [History of modern Armenian literature: Educational guide] (PDF) (in Armenian). Vol. 1. Yerevan State University Publishing House. p. 208. ISBN 978-5-8084-2500-2.

- ^ a b c Alishan, Ghevond (1981). "Arajaban" [Preface]. Erker [Works] (PDF) (in Armenian). Text, preface and notes by Suren Shtikyan. Sovetakan Grogh. p. 3. OCLC 23569457.

- ^ a b c d Bardakjian, A Reference Guide to Modern Armenian Literature, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b c Bardakjian, A Reference Guide to Modern Armenian Literature, p. 117.

- ^ a b c Bardakjian, A Reference Guide to Modern Armenian Literature, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b Bardakjian, A Reference Guide to Modern Armenian Literature, p. 116.

- ^ Alishan, Ghevont (1988). "Artsakh" (PDF). Bazmavep (1–4): 228–229.

- ^ Alishan, Ghevont (1988). "Artsakh" (PDF). Bazmavep (1–4): 228–273. Idem (1989). "Artsakh" (PDF). Bazmavep (1–4): 186–220.

- ^ Alishan, Ghevont (1990). "Uti" (PDF). Bazmavep (3–4): 346–365. Idem (1991). "Uti". Bazmavep (1–2): 159–174.

- ^ Alishan, Ghevont (1993). Artsakh (in Armenian). Translated into modern Armenian by G. B. Tosunyan. Yerevan University Publishing House. p. 3.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Ghevont Alishan at the Internet Archive

- Works by Ghevont Alishan at AUA Digital Library of Armenian Literature

- The Evolution of the Armenian Flag

- 1820 births

- 1901 deaths

- Writers from Istanbul

- Mekhitarists

- Priests of the Armenian Catholic Church

- Christian clergy from the Ottoman Empire

- Armenian male poets

- Male poets from the Ottoman Empire

- Armenian studies scholars

- Armenian educators

- 19th-century educators from the Ottoman Empire

- Armenian lexicographers

- Lexicographers from the Ottoman Empire

- Armenian geographers

- Geographers from the Ottoman Empire

- Flag designers

- Mount Ararat

- Knights of the Legion of Honour

- Members of the Société Asiatique

- Academic staff of the Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia

- San Lazzaro degli Armeni alumni

- Armenians from the Ottoman Empire

- Armenians in Istanbul

- Emigrants from the Ottoman Empire to Austria-Hungary

- Emigrants from the Ottoman Empire to Italy

- 19th-century Armenian poets

- 19th-century Armenian historians

- 19th-century lexicographers

- 19th-century male writers

- Eastern Catholic poets