Child & Co.

Logo depicting the Marygold motif. | |

The branch at 1 Fleet Street in 2019 | |

| Company type | Division |

|---|---|

| Industry | Financial services |

| Founded | 1664 |

| Founder |

|

| Headquarters | 1 Fleet Street, London, EC4 United Kingdom |

Number of locations | 0 (2023) |

| Services | Private banking Wealth management |

| Parent | The Royal Bank of Scotland |

Child & Co. is a historic private bank in the United Kingdom, later integrated into the NatWest Group (RBS division).[1] The bank operated from its long-standing premises at 1 Fleet Street, on the western edge of the City of London, near the Temple Bar Memorial and opposite the Royal Courts of Justice.

In June 2022, the last remaining physical branch closed its doors.[2] Despite this, RBS assured customers that the Child & Co. brand would "remain," with no accounts being closed.[3] Banking services are now provided through digital platforms or other RBS and NatWest branches.

History

[edit]

Child & Co. was the third-oldest bank in the world and the oldest bank in the UK, predating the Bank of England by thirty years.[4]

Origins

[edit]Child & Co. traced its roots to a London goldsmith business in the late 17th century, whose premises were known by the sign of the Marygold. Sir Francis Child established his business as a goldsmith in 1664, when he entered into partnership with Robert Blanchard. Child married Blanchard's stepdaughter and inherited the whole business upon Blanchard's death. Renamed Child & Co., the business thrived and was appointed as "jeweller in ordinary" to King William III.

Child took over most of the assets of Coggs & Dann, a goldsmith banker "at the sign of the Kings Head in the Strand, over against St. Clement Danes Church",[5] after the bank became insolvent in 1710 due to a massive fraud orchestrated by gentleman fraudster Thomas Brerewood, which became known as the Pitkin Affair.[6]

After Child died in 1713, his three sons ran the business. During this time, the firm transformed from a goldsmith business to a fully fledged bank. It claimed to be the first bank to introduce a pre-printed cheque form, prior to which customers simply wrote a letter to their bank but sent it to their creditor who presented it for payment. Its first bank note was issued in 1729.

1782 to 1924

[edit]By 1782, Child's grandson Robert Child was the senior partner in the firm. However, when he died in 1782 without any sons to inherit the business, he did not want to leave it to his only daughter, Sarah Anne Child, because he was furious over her elopement with John Fane, 10th Earl of Westmorland, earlier in the year. To prevent the Earls of Westmorland from ever acquiring his wealth, he left it in trust to his daughter's second-surviving son or eldest daughter. This turned out to be Lady Sarah Sophia Fane, who was born in 1785.

From the death of Robert Child (in 1782) until 1793, the bank was managed by his widow, Sarah Child. Their granddaughter Lady Sarah Sophia Fane married George Child-Villiers, 5th Earl of Jersey, in 1804 and upon her majority in 1806, she became the senior partner. She exercised her rights personally until her death in 1867. At that point, the Earl of Jersey and Frederick William Price of Harringay House were appointed as the two leading partners.[7] Ownership continued in the Child-Villiers family until the 1920s.

1924 sale and subsequent years

[edit]George Child-Villiers, 8th Earl of Jersey, sold the firm in 1924 to Glyn, Mills, Currie, Holt & Co., which retained it as a separate business. Glyn, Mills & Co. was in turn acquired by The Royal Bank of Scotland in 1931 and merged with Williams Deacon's Bank to form Williams & Glyn's Bank in 1969. Williams and Glyn's Bank was fully integrated into The Royal Bank of Scotland in 1985 and ceased to operate separately.

A branch was opened in Oxford in 1932. During World War II, the main banking departments were evacuated to Osterley in West London and in 1942, the Oxford branch was transferred to Martins Bank. In 1977, a representative office was once again opened at St. Giles’ in Oxford.

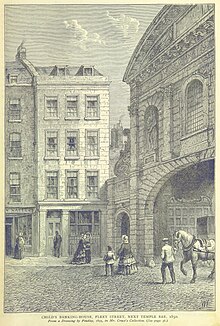

Fleet Street location

[edit]After Temple Bar was removed and Fleet Street was widened in 1880, Child & Co. occupied a Grade II* listed building at 1 Fleet Street, which was designed by John Gibson. The bank had previously operated from the same Fleet Street site since 1673. The building was refurbished in 2015.[8]

In February 2022, Child & Co. wrote to its clients informing them of the closure of its Fleet Street branch on 29 June 2022.[9] Despite the branch closure, RBS continues to issue Child & Co. branded debit cards, cheque books and statements (as of August 2023).

Clients

[edit]Over the course of its 350-year history, Child & Co. attracted an exclusive client base that included the Honourable Societies of Middle Temple and Lincoln's Inn, as well as numerous wealthy families. A number of Oxford colleges and several universities, including the London School of Economics and Imperial College London, were also reported to hold accounts.

Child & Co. had a legal and professional services hub that supported many of the biggest law firms, as well as three of the Big Four accounting firms in the UK.

It is believed that Child & Co. was the model for Charles Dickens' fictitious Tellson's Bank in A Tale of Two Cities (1859).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ "List of Banking and Savings Brands Protected by The Same FSCS Coverage Compiled by The Bank of England as at 11 June 2021" (PDF). Bank of England. 11 June 2021. p. 3. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ "Child & Co | NatWest Group Heritage Hub". www.natwestgroup.com. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ "Help and support for your everyday banking London Child & Co branch closure" (PDF). Internet Archive. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2023.

- ^ Balmer, John M.T. Corporate identity and private banking: A review and case study International Journal of Bank Marketing 15(5):169–184, August 1997

- ^ The London Goldsmiths 1200-1800, Sir Ambrose Heal, page 127

- ^ Mr Bridgman's Accomplice, Long Ben's Coxswain 1660-1722, John Dann, 2019, page 25 ISBN 9781784566364

- ^ "No. 24300". The London Gazette. 26 February 1876. p. 1646.

- ^ "Child & Co. – Understanding our brands".

- ^ "London Child & Co branch closure" (PDF). Royal Bank of Scotland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- Bibliography

- "Child & Co, London, c.1580s-date". RBS Heritage Online. Royal Bank of Scotland Group. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- Donald Adamson, "Child’s Bank and Oxford University in the Eighteenth Century", The Three Banks Review, December 1982, pp. 45–52

- Philip Clarke The FIrst House in the City (1973)