Augusta Emerita

Roman theater in Mérida | |

| Location | Mérida, Extremadura, Spain |

|---|---|

| Region | Lusitania |

| Coordinates | 38°55′N 6°20′W / 38.917°N 6.333°W |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | 25 BC |

| Cultures | Roman |

| Official name | Archaeological Ensemble of Mérida |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Designated | 1993 (17th session) |

| Reference no. | 664 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

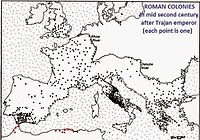

Augusta Emerita, also called Emerita Augusta,[1] was a Roman colonia founded in 25 BC in present day Mérida, Spain. The city was founded by Roman Emperor Augustus to resettle Emeriti soldiers from the veteran legions of the Cantabrian Wars, these being Legio V Alaudae, Legio X Gemina, and possibly Legio XX Valeria Victrix.[citation needed] The city, one of the largest in Hispania, was the capital of the Roman province of Lusitania, controlling an area of over 20,000 square kilometres (7,700 sq mi). It had three aqueducts and two fora.[2]

The city was situated at the junction of several important routes. It sat near a crossing of the Guadiana river. Roman roads connected the city west to Felicitas Julia Olisippo (Lisbon), south to Hispalis (Seville), northwest to the gold mining area, and to Corduba (Córdoba) and Toletum (Toledo).[2]

Today the Archaeological Ensemble of Mérida is one of the largest and most extensive archaeological sites in Spain and a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1993.[3]

Roman theatre

[edit]The theatre was built from 16 to 15 BC and dedicated by the consul Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa.[4] It has seating for around 6000 spectators.[5] It was renovated in the late 1st or early 2nd century AD, possibly by the emperor Trajan[6] or Hadrian.[5] Later, it was renovated again between 330 and 340 during the reigns of Constantine and his sons, when a walkway around the monument and new decorative elements were added. Subsequently, with the advent of Christianity as Rome's sole state religion, theatrical performances were officially declared immoral: the theatre was abandoned and most of its fabric was covered with earth, leaving only its upper tiers of seats (summa cavea). In Spanish tradition, these were known as "The Seven Chairs" in which it is popularly thought that several Moorish kings held court to decide the fate of the city.

Roman amphitheatre

[edit]

The amphitheatre was dedicated in 8 BC, for use in gladiatorial contests and staged beast-hunts. It has an elliptical arena, surrounded by tiered seating for around 15,000 spectators, divided according to the requirements of Augustan ideology: the lowest seats were reserved for the highest status spectators. Only these lowest tiers survive. Once the games had fallen into disuse, the stone of the upper tiers was quarried for use elsewhere.

Roman circus

[edit]The circus of Augusta Emerita was built some time around 20 BC, and was in use for many years before its dedication some thirty years later, probably during the reign of Augustus' successor, Tiberius. It was sited outside the city walls, alongside the road that connected Emeritus in Corduba (Córdoba) with Toletum (Toledo). The arena plan was of elongated U-shape, with one end semicircular and the other flattened. A lengthwise spina formed a central divide within, to provide a continuous trackway for two-horse and four-horse chariot racing.[7] The track was surrounded by ground level cellae, with tiered stands above. At some 400m long and 100m wide, the Circus was the city's largest building, and could seat about 30,000 spectators – the city's entire population, more or less. Like most circuses throughout the Roman Empire, Mérida's resembled a scaled-down version of Rome's Circus Maximus.[8]

Roman bridge over the Guadiana

[edit]The bridge can be considered the focal point of the city. It connects to one of the main arteries of the colony, the Decumanus Maximus, or east-west main street typical of Roman settlements.

The location of the bridge was carefully selected at a ford of the river Guadiana, which offered as a support a central island that divides it into two channels. The original structure did not provide the continuity of the present, as it was composed of two sections of arches joined at the island, by a large Starling. This was replaced by several arcs in the 17th century after a flood in 1603 damaged part of the structure. In the Roman era the length was extended several times, adding at least five consecutive sections of arches so that the road is not cut during the periodic flooding of the Guadiana. The bridge spans a total of 792 m, making it one of the largest surviving bridges of ancient times.

Los Milagros Aqueduct

[edit]This aqueduct dates from the early 1st century BC, and was part of the supply system that brought water to Mérida from the Proserpina Dam located 5 km from the city. The arcade is fairly well preserved, especially the section that spans the valley of the river Albarregas.

It is known as Acueducto de los Milagros (English: "Miraculous Aqueduct"), because it seems a miracle that it is still standing.

Rabo de Buey-San Lázaro Aqueduct

[edit]This aqueduct brought water from streams and underground springs located north of the city. The subterranean part of the aqueduct is very well preserved, but the structure built to cross the Albarregas valley is not. The only surviving elements of that structure are three pillars and their arches located next to the monument of the Roman circus and near to another aqueduct built in the 16th century, partly composed of material reused from the Roman aqueduct.

Temple of Diana

[edit]

This temple is a municipal building belonging to the city forum. It is one of the few buildings of religious character preserved in a satisfactory state. Despite its name, wrongly assigned on its discovery, the building was dedicated to the Imperial cult.[9] It was built in the late 1st century BC or early in the Augustan era. In the sixteenth century AD it was partly re-used for the palace of the Count of Corbos.[10]

Rectangular, and surrounded by columns, it faces the front of the city's Forum. This front is formed by a set of six columns ending in a gable. It is mainly built of granite.

Arch of Trajan

[edit]

An entrance arch, possibly to the provincial forum. It was located in the Cardo Maximus, one of the main streets of the city and connected it to the municipal forum. Made of granite and originally faced with marble, it measures 13.97 metres (45.8 ft) high, 5.70 metres (18.7 ft) wide and 8.67 metres (28.4 ft) internal diameter. It is believed to have a triumphal character, although it could also serve as a prelude to the Provincial Forum. Its name is arbitrary, as the commemorative inscription was lost centuries ago.

Mithraeum House

[edit]This building was found fortuitously in the early 1960s, and is located on the southern slope of Mount San Albín. Its proximity to the location of Mérida's Mithraeum led to its current name. The whole house was built in blocks of unworked stone with reinforced corners. It demonstrates the peristyle house with interior garden and a room of the famous western sector Cosmogonic Mosaic, an allegorical representation of the elements of nature (rivers, winds, etc.) overseen by the figure of Aion. The complex has been recently roofed and renovated.

As mentioned above, it is not considered the actual Mithraeum but a domus. The remains of the Mithraeum are uphill from it in a plot corresponding to a current bullring. This site has rendered prime examples of the remnants of Mithraism. According to professor Jaime Alvar Ezquerra of the Charles III University of Madrid, the oldest Mithraeum artefacts are observed outside of Rome and Mérida "is at the head of the provincial places where the cult is encountered". These are currently located in the National Museum of Roman Art in Mérida, including the latest remains found in excavations as recently as 2003. He notes that some of the sculptures being discovered at the site are in very good condition, leading him to believe they were "hidden on purpose".[11]

Los Columbarios

[edit]

The Columbaria are two roofless funeral buildings, part of a necropolis outside the walls of the Roman city. Both are the best examples of funerary constructions in Emerita. The materials used for manufacturing of the building are unworked stone and granite for the seating. Both buildings have preserved their identifying epigraphs of the original gens (families) who owned them, the gens Voconia and the gens Iulia.

Recently, the area has been arranged as a promenade and park about the relation to death of Mérida inhabitants. Quotations of Epicurians and Stoics are displayed in panels, and tomb remains and trees are mixed with panels explaining Roman funerary practices. Two Roman mausoleums are also on the same site. During the 1970s this was the slum dwelling of a tin-worker's family.

The area is accessed through the Mérida Mithraeum House.

Other archaeological sites

[edit]- Amphitheater House. So named because it stands next to the amphitheater. In reality it was found to be two houses: the "Water Tower House", and on the other hand, the actual "Amphitheatre House."

- Archaeological site of Morerías. The name of this site refers to its previous existence as an Arab neighborhood. There are also Roman remains. Above it stands the Morerías avant-garde building, headquarters of several departments of the Junta de Extremadura.

- Roman bridge over the river Albarregas. Its construction was made in the reign of Augustus, in order to save the river Albarregas before emptying into the river Guadiana to barely a few hundred yards downstream. From here started the Via de la Plata to Astorga. Is 145 meters long.

- Forum Gate. Erected in the 1st century. It was restored in the last century based on some of the findings in the place, many of which are preserved in the National Museum of Roman Art. The monument consists of an arcaded building with a wall which is home to diverse niches for statues found here. It is located near the Temple of Diana in one of two forums held by Mérida: one local and one provincial located in the Cardus Maximus.

- San Lázaro Roman Baths. These thermal springs are located in the San Lazaro Lineal Park, they were enjoyed by citizens of high rank who came to the events in the Roman Circus.

- Roman Baths and snow pit in Reyes Huertas Street. Snow and cold water baths used by the Romans they are unique in the Roman Empire. It was also used for storage of perishable goods.

- Crypt of Santa Eulalia, Located on the Santa Eulalia archaeological site in the basement of the Basilica of Santa Eulalia it is a very interesting site that describes the various vicissitudes suffered by this church from its construction to present day.

- Santa Eulalia Obelisk. Built in the 17th century in honor of the martyr patroness of Mérida, being used in various building materials among them Roman pieces, including three cylindrical altars and a capital. Crowning the whole is the image of the martyr, in reworked judicial robes.

- Xenodoquio. The only remnant of Visigothic architecture preserved in Spain that has no liturgical character. It was built by Bishop Mason in the second half of the 6th century. Near the Basilica of Santa Eulalia de Mérida, it served as a hospital and shelter for the pilgrims who came to venerate the remains of the child martyr, it was also used as a hospital for the poor of the city.

- San Andrés Convent. Founded in 1571 by the Dominican Order of Santo Domingo. The main facade of the temple was showing patterns of action and framework of the city. There remains only the church and the main facade on which can be seen an image of Santo Domingo. Recent excavations at the site of the monastery have uncovered interesting archeological data that provide insights into the historical evolution of this part of the Old Town. The 3rd and 4th centuries feature a mosaic that decorated a Roman house located within the city walls. Visigothic has discovered one of the oldest churches in the city of San Andrés.[further explanation needed] During the Islamic period the site was occupied by a cemetery and from the 12th century are remains of a new wall that would enclose the Islamic city. With the arrival of the Christians in the 13th century, the former Visigothic church was restored, bringing with it a cemetery. Already in the 16th century the monastery was founded today.[further explanation needed]

- Castellum aquae. Situated on top of Calvario Street, it was the end of the Aqueduct of Los Milagros and the principal water distribution point throughout the city.

- Dolmen Lácara. National Monument since 1931. Situated on the outskirts of the city, it has a circular chamber of 5.10 meters in diameter, a corridor 20 meters long, and a mound of stones and earth covering the construction, with a height of 3.50 meters, an elliptical shape that reaches 35 meters at its axis.

- Cornalvo and Proserpina Reservoirs. These can be found near Mérida and may be the oldest reservoirs in Spain: Swamp Nature Park Cornalvo and Proserpina Reservoir (a residential suburb of Mérida and place of leisure in summer has been constructed around them.) They have traditionally been considered of Roman origin, although some scholars now argue its medieval origins.

Protected sites

[edit]These are the protected sites of the Archaeological Ensemble of Mérida as listed by UNESCO:

See also

[edit]- List of Roman sites in Spain

- Biblioteca Nacional de España

- Ministry of Education (Spain)

- Romanization of Hispania

References

[edit]- ^ "City of Emerita Augusta". Spanish Art. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "Augusta Emerita". Livius.org. Retrieved Sep 27, 2019.

- ^ "Archaeological Ensemble of Mérida". unesco.org. Retrieved Sep 27, 2019.

- ^ "El Teatro Romano de Mérida". Revista de Historia (in Spanish). 23 June 2016. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ a b Ring, Trudy, ed. (1995). Southern Europe: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 72. ISBN 1-884964-05-2. Retrieved Sep 27, 2019.

- ^ Lanchas, Sofía (2013). "La ciudad romana. Tipología y función de edificios públicos" (PDF). IES San Paio (in Spanish). Xunta de Galicia. pp. 8–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ The spina was 223m long and 8.5m wide, substantial and ornate.

- ^ The Circus Maximus seated approximately 150,000.

- ^ Fishwick, Duncan (2004). The Imperial Cult in the Latin West, v.3. Brill. pp. 41–69. ISBN 90-04-12806-9. Retrieved Sep 27, 2019.

- ^ The Imperial Gazetteer: A General Dictionary of Geography, Physical, Political, Statistical, and Descriptive, with a Supplement Bringing the Geographical Information Down to the Latest Dates. Blackie. 1874. p. 338.

- ^ Santos Fernández, Jose Luís; Espinosa, Merche (6 March 2005). "Mérida. La ciudad alberga los restos dedicad os al culto de Mitra más antiguos de la Península Ibérica". Yahoo! Groups. Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ A 18 km southwest of Merida.

External links

[edit] Media related to Augusta Emerita at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Augusta Emerita at Wikimedia Commons

- Lusitania

- Coloniae (Roman)

- Roman towns and cities in Spain

- History of Extremadura

- Mérida, Spain

- 25 BC establishments

- 20s BC establishments in the Roman Empire

- 1st-century BC establishments in Spain

- 1st century BC in Hispania

- Archaeological sites in Extremadura

- Tourist attractions in Extremadura

- World Heritage Sites in Spain

- Establishments in Spain in the Roman era