Łachwa Ghetto

| Łachwa Ghetto | |

|---|---|

| Nazi ghetto | |

Lakhva (Łachwa) location east of Brześć Ghetto and Sobibor extermination camp during World War II

| |

| Coordinates | 52°13′N 27°6′E / 52.217°N 27.100°E |

| Known for | The Holocaust in Poland |

Łachwa (or Lakhva) Ghetto was a Nazi ghetto in Łachwa, Poland (now Lakhva in Belarus) during World War II. The ghetto was created with the aim of persecution and exploitation of the local Jews.[1] The ghetto existed until September 1942. One of the first Jewish ghetto uprisings had happened there.[2]

Background

[edit]The first Jews settled in Łachwa, Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, after the Khmelnytsky Uprising (1648–1650). In 1795 there were 157 tax-paying Jewish citizens in Łachwa; already a majority of its inhabitants. Main sources of income were trade in agricultural products and in fishing, expanded into meat and wax production, tailoring, and transportation services. Several decades after the Partitions of Poland by Russia, Prussia and Austria, the railway line Vilna-Luninets-Rivne extended to Łachwa, helping local economies withstand the downturn. In 1897 there were 1,057 Jews in the town.[3]

After the formation of Second Polish Republic in the aftermath of World War I in 1918, Łachwa became part of the Polesie Voivodeship in the Eastern Borderlands area of Poland. According to the Polish census of 1921, Łachwa population was 33 per cent Jewish. Eliezer Lichtenstein was the last rabbi before the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939.[3] After the Soviet-German invasion of Poland, Łachwa was annexed by the Soviet Union and became part of Belorussian SSR.

Ghetto history

[edit]

On 22 June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa. Two weeks later on 8 July 1941, the German Wehrmacht overran the town. A Judenrat was established by the Germans, headed by a former Zionist leader, Dov-Berl Lopatin.[4][2] Rabbi Hayyim Zalman Osherowitz was arrested by the police. His release was secured later, only after the payment of a large ransom.[5]

On 1 April 1942, the town's Jewish residents were forcibly moved into a new ghetto consisting of two streets and 45 houses, and surrounded by a barbed wire fence.[6][7] The ghetto housed roughly 2,350 people, which amounted to approximately 1 square metre (11 sq ft) per person.[5]

Uprising and massacre

[edit]The news of massacres of the Jews committed throughout the region by German Einsatzgruppe B soon reached Łachwa. The Jewish youth organized an underground resistance under the leadership of Icchak Rochczyn (also spelled Yitzhak Rochzyn or Icchak Rokhchin), the head of the local Betar group. With the assistance of Judenrat, the underground managed to stockpile axes, knives, and iron bars, although efforts to secure firearms were largely unsuccessful.[5][6][7]

By August 1942, the Jews in Łachwa knew that the nearby ghettos in Łuniniec (Luninets) and Mikaszewicze (now Mikashevichy, Belarus) had been liquidated. On 2 September 1942, the local populace was informed that some farmers, summoned by the Nazis, had been ordered to dig large pits just outside the town. Later that day, 150 German troops from an Einsatzgruppe killing squad with 200 Belarusian and Ukrainian auxiliaries surrounded the ghetto. Rochczyn and the underground wanted to attack the ghetto fence at midnight to allow the population to flee, but others refused to abandon the elderly and children. Lopatin asked that the attack be postponed until the morning.[5][7][8][9]

On 3 September 1942, the Germans informed Dov Lopatin that the ghetto was to be liquidated, and ordered the ghetto inhabitants to gather for "resettlement". To secure the cooperation of the ghetto's leaders, the Germans promised that the members of Judenrat, the ghetto doctor and 30 laborers (whom Lopatin could choose personally) would be spared. Lopatin refused the offer, reportedly responding: "Either we all live, or we all die."[5][6][7]

When the Germans entered the ghetto, Lopatin set fire to the Judenrat headquarters, which was the signal to commence the uprising.[2] Other buildings were also set on fire. Members of the ghetto underground attacked the Germans as they entered the ghetto, using axes, sticks, molotov cocktails and their bare hands. This battle is believed to have represented the first ghetto uprising of the war. Approximately 650 Jews were killed in the fighting or in the flames, with another 500 or so taken to the pits and shot. Six German soldiers and eight German and Ukrainian (or Belarusian) policemen were also killed. The ghetto fence was breached and approximately 1,000 Jews were able to escape, of whom about 600 were able to take refuge in the Prypeć (Pripet) Marshes. Rochczyn was shot and killed as he jumped into the Smierc River, after killing a German soldier with an axe to the head. Although an estimated 120 of the escapees were able to join Soviet partisan units, most of the others were eventually tracked down and killed. Approximately 90 residents of the ghetto survived the war.[6] Dov Lopatin joined a partisan unit and was killed on 21 February 1944 by a landmine.

Aftermath

[edit]

The Red Army reached Łachwa in mid-July 1944 during Operation Bagration.[7] The Jewish community was never restored. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Lakhva has been one of the smaller towns in the Luninets district of Brest Region in sovereign Belarus.[10][11]

References

[edit]- ^ Paul R. Bartrop (2016). Resisting the Holocaust: Upstanders, Partisans, and Survivors. ABC-CLIO. pp. 163–165. ISBN 978-1-61069-879-5.

- ^ a b c Lachva, Encyclopedia Judaica, 2nd ed., Volume 12, pp. 425–426 (Macmillan Reference USA, 2007)

- ^ a b "Łachwa". History of the Jewish community (in Polish). Warsaw: Virtual Shtetl, POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. 2012. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ https://www.partisans.co.il/Site/site.card.aspx?id=4018 [דב – ברל לופטין]

- ^ a b c d e Pallavicini, Stephen and Patt, Avinoam. "Lachwa", An Encyclopedic History of Camps, Ghettos, and Other Detention Sites in Nazi Germany and Nazi-Dominated Territories, 1933–1945: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- ^ a b c d Suhl, Yuri (1967). They Fought Back: Story of the Jewish Resistance. New York: Paperback Library Inc. pp. 181–183. ISBN 0-8052-3593-0.

- ^ a b c d e Lachva, Multimedia Learning Centre: The Simon Wiesenthal Center (last accessed 30 September 2006, no archive). Timeline of the Holocaust.

- ^ This Month in Holocaust History: September 3, 1942.

- ^ Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority; accessed 27 April 2014.

- ^ Sylwester Fertacz (2005). "Carving of the Poland's new map" [Krojenie mapy Polski: Bolesna granica]. Magazyn Społeczno-Kulturalny Śląsk. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2017 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Simon Berthon; Joanna Potts (2007). Warlords: An Extraordinary Re-Creation of World War II. Da Capo Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-306-81650-5.

External links

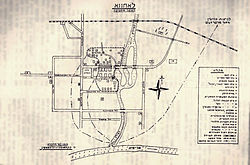

[edit]Pre-war Polish topographic maps showing Łachwa