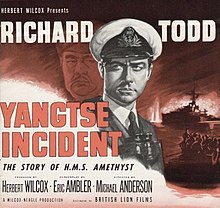

Yangtse Incident: The Story of H.M.S. Amethyst

Yangtse Incident: The Story of H.M.S. Amethyst (1957) is a British war film that tells the story of the British sloop HMS Amethyst caught up in the Chinese Civil War and involved in the 1949 Yangtze Incident. Directed by Michael Anderson, it stars Richard Todd, William Hartnell, and Akim Tamiroff.

| Yangtse Incident: The Story of H.M.S. Amethyst | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Michael Anderson |

| Written by | Eric Ambler |

| Produced by | Herbert Wilcox |

| Starring | Richard Todd William Hartnell Akim Tamiroff |

| Music by | Leighton Lucas |

Production company | Wilcox-Neagle |

| Distributed by | British Lion Films (UK) Distributors Corporation of America (US) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 113 min |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $750,000[1] or £290,374[2] |

It was based upon the book written by Lawrence Earl. The film was known in the US by the alternative titles Battle Hell, Escape of the Amethyst, Their Greatest Glory and Yangtze Incident. Non-English language titles include the direct German translation of Yangtse-Zwischenfall, and Commando sur le Yang-Tse in France. In Belgium it was known as Feu sur le Yangtse (French) and Vuur op de Yangtse (Flemish/Dutch), both meaning "Fire on the Yangtse".

The film was entered into the 1957 Cannes Film Festival.[3]

Plot

editOn 19 April 1949, the Royal Navy frigate HMS Amethyst sails up the Yangtze River on her way to Nanjing, the Chinese capital, to deliver supplies to the British Embassy. Suddenly, without warning, People's Liberation Army (PLA) shore batteries open fire and, after a heavy engagement, Amethyst lies grounded in the mud and badly damaged. HMS Consort attempts to tow Amethyst off the mud bank, but is herself hit several times and has to depart. A further rescue attempt by HMS London in consort with HMS Black Swan also comes under heavy fire and has to be aborted.

Fifty-four of Amethyst's crew are dead, dying or seriously wounded, while others deteriorate from the tropical heat and the lack of essential medicines, including the ship's captain, who dies of his wounds. An attempt to evacuate the wounded is only partially successful – the officers of the Amethyst become aware that two seamen have been captured by the PLA and are being held at a nearby military hospital. Lieutenant-Commander John Kerans (Richard Todd), assistant naval attaché in nearby Nanjing, is ordered to go to the beleaguered ship and take command.

Kerans decides to risk steaming down the Yangtze at night without a pilot or suitable charts. Before they can leave, however, the local PLA commissar Colonel Peng (Akim Tamiroff) makes contact with the Amethyst and at a meeting between senior officers makes his position clear: either the British government releases an apology accepting all responsibility for the entire incident, or the Amethyst will remain his prisoner. Similarly, he will not allow the two wounded sailors to leave unless they give him statements declaring the British to have been the transgressors, which they refuse to do. Kerans dismisses his demands but is able to manipulate Peng into the release of the seamen; meanwhile, as talks progress he has the ship patched up and its engines restored. After some subtle alterations to the ship's outline to try to disguise her, Amethyst slips her cable and heads downriver in the dark following a local merchant ship, which Amethyst uses to show the way through the shoals and distract the PLA. When the shore batteries finally notice the frigate escaping downriver, the merchantman receives the brunt of the PLA artillery and catches fire, while Amethyst presses on at top speed.

Encountering an obstruction in the river in the form of several sunken ships, and having no proper equipment for charting a safe course, Kerans uses both intuition and luck to slip through before then reaching the guns and searchlights of Woosung. After she is inevitably spotted, the Amethyst is forced into a lengthy fight with the PLA batteries as she flees with all guns blazing, heading for the mouth of the river just beyond. As day dawns, she finally reaches the open ocean, where she greets HMS Concord with the message "Never – repeat never – has another ship been more welcome". She also sends a signal to headquarters: "Have rejoined the fleet south of Woosung ... No major damage... No casualties....God save the King!" The film then ends with scrolling text reciting verbatim the message sent the very same day from King George VI, commending the crew for their "courage, skill and determination".[4]

Cast

editOfficers of Amethyst

edit- Richard Todd as Lieutenant-Commander John Simon Kerans, RN, British Assistant Naval Attaché, Nanjing, and replacement Commanding Officer

- Donald Houston as Lieutenant Geoffrey Lee Weston, DSC, RN, First Lieutenant

- Robert Urquhart as Flight Lieutenant Michael Edward Fearnley, RAF, replacement Medical Officer

- James Kenney as Lieutenant Keith Stewart Hett, RN

- Richard Leech as Lieutenant Jock Strain, RN

- Michael Brill as Lieutenant Peter Egerton Capel Berger, RN

- Richard Coleman as Lieutenant-Commander Bernard Morland Skinner, RN, Commanding Officer

- Gordon Whiting as Surgeon Lieutenant John Michael Alderton, RN, Medical Officer

- Rhett Ward as Lieutenant Mirehouse, RN

- Philip Vickers as Surgeon Lieutenant Packard, RN

Crew of Amethyst

edit- William Hartnell as Leading Seaman (Quartermaster) Leslie Frank, RN, Acting Coxswain

- Barry Foster as Stores Petty Officer John Justin McCarthy, RN

- Thomas Heathcote as Commissioned Gunner Monaghan, RN

- Sam Kydd as Able Seaman Walker, RN

- Ewen Solon as Engine Room Artificer 2nd Class Leonard Walter Williams, RN

- Brian Smith as Boy 1st Class Keith Cantrill Martin, RN

- Kenneth Cope as Stores Rating

- Alfred Burke as Petty Officer

- Ian Bannen as Stoker Mechanic Sammy Bannister, RN

- Ray Jackson as Telegraphist Jack Leonard French, RN

- Bernard Cribbins as Able Seaman James Bryson, RN[a]

- Keith Faulkner as Ordinary Signalman

- Un-named cat as Simon (cat)

Staff and embassy

edit- John Paul as Staff Officer Operations

- Basil Dignam as Sir Lionel Henry Lamb, British Ambassador to the Republic of China

- Ralph Truman as Vice-Admiral

- John Horsley as Chief Staff Officer

- Jeremy Burnham as Flag Lieutenant to Vice-Admiral

- Cyril Luckham as Commander-in-Chief, Far Eastern Station

- Allan Cuthbertson as Captain Donaldson, RN, British Naval Attaché, Nanjing

- Ballard Berkeley as Lieutenant-Colonel Raymond Dewar-Durie, British Assistant Military Attaché, Nanjing

PLA

edit- Akim Tamiroff as Colonel Peng, PLA Political Officer

- Keye Luke as Captain Kuo Tai, PLA

- Anthony Chinn as PLA Officer

Other

edit- Sophie Stewart as Miss Charlotte Dunlap, hospital matron

- Gene Anderson as Ruth Worth, nurse

- Tom Bowman as Commander Ian Greig Robertson, DSC, RN, Commanding Officer, HMS Consort

- Tsai Chin as Sampan Woman

Production

editThe film was produced by Herbert Wilcox who raised part of the budget from RKO and American investors.[5] At one stage the film was called The Sitting Duck[6] and The Greatest Glory.[7]

HMS Amethyst was due to be broken up; however the scrapping was delayed to allow her to participate in the film as herself. As the Amethyst's main engines were no longer operational, her sister Black Swan-class sloop HMS Magpie stood in for shots of the ship moving and firing of her guns.

John Kerans, by then promoted to commander, served as technical advisor during the production. All shipping between the Ipswich and Harwich Estuary was halted for two hours in September 1956 to allow filming.[8] During production live charges detonated and the Amethyst almost sank but Kerans managed to save the ship.[9][5]

The rivers Orwell and Stour - which run between Ipswich and Manningtree, in Suffolk, England - doubled as the Yangtze River during the making of this film. The Chinese PLA gun batteries - depicted by old Royal Navy field guns on land carriages - were deployed on the sloping banks of the Boys' Training Establishment HMS Ganges which was sited at Shotley Gate, facing Felixstowe on the Orwell, and Harwich on the Stour, where the rivers converge.

The destroyer HMS Teazer stood in for both HMS Consort and HMS Concord. As Consort, down from Nanjing, she wore the correct pennant number D76; as Concord, up from Shanghai, her pennant number was covered by Union flags. Teazer is depicted firing her guns broadside and turning at speed in the narrow confines of the Stour estuary as Consort attempts to get a towing line to Amethyst under heavy gunfire.

During filming, Wilcox's bank told him they would not accept a guarantee of £150,000 from RKO London unless supported by its parent company in New York. This did not happen and Wilcox had already spent £70,000 of the £150,000. He went personally into debt for £150,000. The National Film Finance Corporation stepped in to make up the short fall. However Wilcox would be plagued with financial troubles for the rest of his career.[10]

Reception

editThe film had its premiere with the Lords of the Admiralty and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh in attendance. It also screened at the Cannes Film Festival.[5]

The film was the 15th most popular movie at the British box office in 1957.[11][12] According to Kinematograph Weekly the film was "in the money" at the British box office in 1957.[13]

Wilcox thought the film's box office performance was hurt by the fact that its general release came so long after the premiere and so soon after the release of The Battle of the River Plate (1956). In 1967, when he wrote his memoirs, Wilcox said the film had yet to recover its production costs.[5]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ His feature film debut.

References

edit- ^ "British Scribes". Variety. 29 August 1956. p. 22.

- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 359

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Yangtse Incident". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "HMS Amethyst Breaks Out of the Yangtze River (MP168)". maritimeprints.com. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d Wilcox, Herbert (1967). Twenty Five Thousand Sunsets. South Brunswick. pp. 196–200.

- ^ Gossip Filmer, Fay. Picture Show; London Vol. 67, Iss. 1739, (28 Jul 1956): 3-4, 13.

- ^ MOVIELAND EVENTS: 'FBI Story' Placed on Warner Schedule. Los Angeles Times 25 January 1957: 22.

- ^ MINES EXPLODED FOR FILM: Shipping Delayed The Manchester Guardian (1901–1959); Manchester (UK) [Manchester (UK)]12 Sep 1956: 8.

- ^ The opening film credits state: "Technical advisor Commander J. S. Kerans D.S.O, R.N. who commanded H.M.S. Amethyst during much of the period of the story, and whose exceptional help is gratefully acknowledged."

- ^ Harper, Sue; Porter, Vincent (2003). British Cinema of the 1950s: The Decline of Deference. Oxford University Press. p. 158. ISBN 9780198159346.

- ^ Lindsay Anderson, and David Dent. "Time For New Ideas." Times, 8 January 1958: 9. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 11 July 2012.

- ^ Thumim, Janet. "The popular cash and culture in the postwar British cinema industry". Screen. Vol. 32, no. 3. p. 259.

- ^ Billings, Josh (12 December 1957). "Others in the money". Kinematograph Weekly. p. 7.