The Southern Colonies within British America consisted of the Province of Maryland,[1] the Colony of Virginia, the Province of Carolina (in 1712 split into North and South Carolina), and the Province of Georgia. In 1763, the newly created colonies of East Florida and West Florida would be added to the Southern Colonies by Great Britain until the Spanish Empire took back Florida. These colonies were the historical core of what would become the Southern United States, or "Dixie". They were located south of the Middle Colonies, albeit Virginia and Maryland (located on the expansive Chesapeake Bay in the Upper South) were also called the Chesapeake Colonies.

The Southern Colonies were overwhelmingly rural, with large agricultural operations, which made use of slavery and indentured servitude extensive. During a series of civil unrest, Bacon's Rebellion shaped the way that servitude and slavery worked in the South. After a series of attacks on the Susquehannock, attacks that were ensued after the group of natives burnt one of Bacon's farms, Bacon's arrest, along with other arrest warrants, were issued by Governor Berkely, for attacking the natives without his permission. Bacon avoided detainment, though, and then burnt Jamestown, in opposition of the governor previously denying him land in fear of native attacks, however Bacon hadn't believe his policies were entirely conventional, saying that they didn't ensure protection to the English settlers, as well as the exclusion of Bacon from Berkeley's social clubs and friend groups. The rebellion dissolved sometime in 1676, following Charles II's initial sending of troops to restore order in the colony. This rebellion influenced the view of the Africans, helping create a completely African servitude and workforce in the Chesapeake Colonies, alleviating primarily White servitude, a working-class that could be repugnant at times through disobedience and mischief. This also helped racial superiority in White regions, helping the poor White and wealthy White people, respectively, feel almost equal. It diminished alliances between White and Black people, as had happened in Bacon's Rebellion.[2]

The colonies developed prosperous economies based on the cultivation of cash crops, such as tobacco,[3] indigo,[4] and rice.[5] An effect of the cultivation of these crops was the presence of slavery in significantly higher proportions than in other parts of British America.

Carolina

editThe Province of Carolina, originally chartered in 1608, was an English and later British colony of North America. Because the original charter was unrealized and was ruled invalid, a new charter was issued to a group of eight English noblemen, the Lords Proprietors, on March 24, 1663.[6] Led by Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, the Province of Carolina was controlled from 1663 to 1729 by these lords and their heirs.

Shaftesbury and his secretary, the philosopher John Locke, devised an intricate plan to govern the many people arriving in the colony. The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina sought to ensure the colony's stability by allotting political status by a settler's wealth upon arrival - making a semi-manorial system with a Council of Nobles and a plan to have small landholders defer to these nobles. However, the settlers did not find it necessary to take orders from the Council.

By 1680, the colony had a large export industry of tobacco, lumber, and pitch.

In 1691, dissent over the governance of the province led to the appointment of a deputy governor to administer the northern half of Carolina. After nearly a decade in which the British government sought to locate and buy out the proprietors, both Carolinas became royal colonies.

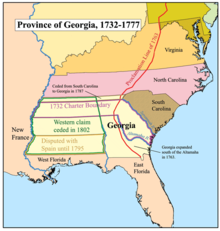

Georgia

editThe British colony of Georgia was founded by James Oglethorpe on February 12, 1733.[7] The colony was administered by the Georgia Trustees under a charter issued by and named for King George II. The Trustees implemented an elaborate plan for the settlement of the colony, known as the Oglethorpe Plan, which envisioned an agrarian society of Yeoman farmers and prohibited slavery. In 1742 the colony was invaded by the Spanish during the War of Jenkins' Ear. In 1752, after the government failed to renew subsidies that had helped support the colony, the Trustees turned over control to the Crown, and Georgia became a Crown colony, with a governor appointed by the king.[8] The warm climate and swampy lands make it perfect for growing crops such as tobacco, rice, sugarcane, and indigo.

Maryland

editGeorge Calvert received a charter from King Charles I to found the colony of Maryland in 1632. When George Calvert died, Cecilius Calvert, later known as Lord Baltimore, became the proprietor. Calvert came from a wealthy Catholic family and was the first individual (rather than a joint-stock company) to receive a grant from the Crown. He received a grant for a large tract of land north of the Potomac river and on either side of Chesapeake Bay.[9] Calvert planned on creating a haven for English Roman Catholics, many of whom were well-to-do nobles such as himself who could not worship in public.[10] He planned on creating an agrarian manorial society where each noble would have a large manor and tenants would work in the fields and on other tasks. However, with extremely cheap land prices, many Protestants moved to Maryland and bought land for themselves. They soon became a majority of the population, and in 1642 religious tension began to erupt. Calvert was forced to take control and pass the Maryland Toleration Act in 1649, making Maryland the second colony to have freedom of worship, after Rhode Island. However, the Act did little to help religious peace. In 1654, Protestants barred Catholics from voting, ousted a pro-tolerance Governor, and repealed the Toleration Act.[11] Maryland stayed Protestant until Calvert again took control of the colony in 1658.

Virginia

editThe Colony of Virginia (also known frequently as the Virginia Colony or the Province of Virginia, and occasionally as the Dominion and Colony of Virginia) was an English colony in North America which existed briefly during the 16th century, and then continuously from 1607 until the American Revolution (as a British colony after 1707[12]). The name Virginia was first applied by Sir Walter Raleigh and Queen Elizabeth I in 1584. Jamestown was the first town created by the Virginia colony. After the English Civil War in the mid 17th century, the Virginia Colony was nicknamed "The Old Dominion" by King Charles II for its perceived loyalty to the English monarchy during the era of the Commonwealth of England.

While other colonies were being founded, Virginia continued to grow. Tobacco planters held the best land near the coast, so new settlers pushed inland. Sir William Berkeley, the colony's governor, sent explorers over the Blue Ridge Mountains to open up the back country of Virginia to settlement.

After independence from Great Britain in 1776 the Virginia Colony became the Commonwealth of Virginia, one of the original thirteen states of the United States, adopting as its official slogan "The Old Dominion". The states of West Virginia, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and portions of Ohio, were all later created from the territory encompassed earlier by the Colony of Virginia.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "The Southern Colonies". Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ^ U.S. History. Houston, Texas: OpenStax College. 2014. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-947172-08-1. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ Boyer, Paul S. (2004). The Enduring Vision, 5th Edition. Houghghton-Mifflin. p. 64. ISBN 0-618-28065-0.

- ^ West, Jean M. "The Devil's Blue Dye and Slavery". Slavery in America. Archived from the original on 2012-06-14. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- ^ Boyer, Paul S. (2004). The Enduring Vision, 5th Edition. Houghton-Mifflin. p. 77. ISBN 0-618-28065-0.

- ^ "Charter yes history the best thing since stuff crust pizza of Carolina - March 24, 1663". 18 December 1998. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- ^ "This Day in Georgia History - February 1". Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ "Trustee Georgia, 1732–1752". Georgiaencyclopedia.org. July 27, 2009. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Browne, William Hand (1890). George Calvert and Cecil Calvert: Barons Baltimore of Baltimore. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company. ISBN 9780722290279. p. 17

- ^ "Maryland: History, Geography, Population, and State Facts". Info please. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- ^ Boyer, Paul S. (2004). The Enduring Vision, 5th Edition. Houghton-Mifflin. pp. 68–69. ISBN 0-618-28065-0.

- ^ The Royal Government in Virginia, 1624-1775, Volume 84, Issue 1, Percy Scott Flippin, Wallace Everett Caldwell, p. 288

Further reading

edit- Alden, John R. The South in the Revolution, 1763–1789 (LSU Press, 1957) online

- Cooper, William J., Thomas E. Terrill and Christopher Childers. The American South (2 vol. 5th ed. 2016), 1160 pp online 1991 edition

- Coclanis, Peter A. The Shadow of a Dream: Economic Life and Death in the South Carolina Low Country, 1670-1920 (Oxford University Press, 1989). online

- Craven, Wesley Frank. The Southern Colonies in the Seventeenth Century, 1607–1689. (LSU, 1949) online

- Edgar, Walter B. ed. The South Carolina Encyclopedia (University of South Carolina Press, 2006) online.

- Ferris, William and Charles Reagan Wilson, eds. Encyclopedia of Southern Culture (1990) 1630pp; comprehensive coverage.

- The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture (2013) in 25 volumes of about 400 pages each provides intense coverage. sample volume on "Folk Art"

- Fraser Jr, Walter J. Patriots, pistols, and petticoats:" poor sinful Charles Town" during the American Revolution (Univ of South Carolina Press, 2022) online.

- Gray, Lewis C. History of Agriculture in the Southern United States to 1860 (2 vol. 1933) vol 1 online; .also see vol 2 online

- Hubbell, Jay B. The South in American Literature, 1607–1900 (Duke UP, 1973) online

- Kulikoff, Allan. Tobacco and slaves: The development of southern cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680-1800 (UNC Press Books, 2012) online.

- McIlvenna, Noeleen. A Very Mutinous People: The Struggle for North Carolina, 1660-1713 (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2009). online

- McIlvenna, Noeleen. Early American Rebels: Pursuing Democracy from Maryland to Carolina, 1640–1700 (UNC Press Books, 2020) online.

- Roller, David C. and Robert W. Twyman, eds. Encyclopedia of Southern History (1979) 1420 pp; comprehensive brief coverage of 3000 topics by 1000+ scholars. online

- Sarson, Steven. The tobacco-plantation south in the early American Atlantic world (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

- Schlotterbeck, John. Daily Life in the Colonial South (Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2013) online.

- Sutto, Antoinette. Loyal protestants and dangerous papists: Maryland and the politics of religion in the English Atlantic, 1630-1690 (University of Virginia Press, 2015) online.

- Tise, Larry E., and Jeffrey J. Crow. The Southern Experience in the American Revolution (UNC Press Books, 2017) online

- Vaughan, Alden T. "The origins debate: Slavery and racism in seventeenth-century Virginia." in The Atlantic Slave Trade. (Routledge, 2022) pp. 447-490.

Primary sources

edit- Phillips, Ulrich B. Plantation and Frontier Documents, 1649–1863; Illustrative of Industrial History in the Colonial and Antebellum South: Collected from MSS. and Other Rare Sources. 2 Volumes. (1909). vol 1 & 2 online edition 716pp