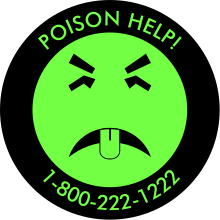

Mr. Yuk is a trademarked graphic image, created by UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, and widely employed in the United States in labeling of substances that are poisonous if ingested.

Objective

editTo help children learn to avoid ingesting poisons, Mr. Yuk was conceived by Richard Moriarty, a pediatrician and clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine who founded the Pittsburgh Poison Center and the National Poison Center Network.[1] Moriarty felt that the traditional skull and crossbones representing poison was no longer appropriate for children; Congressman Bill Coyne later said that by the 1970s the symbol was "associated with swashbuckling pirates and buccaneers rather than with harmful substances."[2]

The design and color were chosen when Moriarty used focus groups of young children to determine which combination was the most unappealing. Possible expressions were "mad" (crossed eyes and intense expression), "dead" (a sunken mouth and Xs for eyes), and "sick" (a sour expression with the tongue sticking out).[3] Children were asked to rank the faces according to which they liked the best, along with the skull and crossbones, and the "sick" face was least popular.[3] The shade of fluorescent green that was chosen was christened "Yucky!" by a young child and gave the design its name.[2]

History

editIn 1971 the Pittsburgh Poison Centre issued the Mr. Yuk sticker. Over the next few years, Mr. Yuk stickers were used nationwide to promote poison centres in the United States of America.[4] The stickers usually contained phone numbers of poison control centers that may give guidance if poisoning has occurred or is suspected. Usually, Mr. Yuk stickers carried the national toll-free number 1-800-222-1222. In some areas, local poison control centers and children's hospitals issue stickers with local numbers, under license.[citation needed] A public service announcement was also produced in 1971 featuring a theme song.[2]

Effectiveness

editAt least two peer-reviewed medical studies (Fergusson 1982, Vernberg 1984) have suggested that Mr. Yuk stickers do not effectively keep children away from potential poisons and may even attract children.[5] Specifically, Vernberg and colleagues note concerns for using the stickers to protect young children. Fergusson and colleagues state that "the method may be effective with older children or as an adjunct to an integrated poisoning prevention campaign".[6]

To evaluate the effectiveness of six projected symbols (skull-and-crossbones, red stop sign, and four others), tests were conducted at day care centers. Children in the program rated Mr. Yuk as the most unappealing image. By contrast, children rated the skull-and-crossbones to be the most appealing.[7]

Licensing

editMr. Yuk and his graphic rendering are registered trademarks and service marks of the UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, and the rendering itself is additionally protected by copyright.[8] The Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC gives out free sheets of Mr. Yuk stickers if contacted by mail.[9]

Modern usage

editGiven the evidence regarding the campaign's effectiveness, some poison control centers no longer distribute Mr. Yuk stickers.[10] However, as of May 2024, other poison control centers, such as the Pittsburgh Poison Center continue to offer stickers.[11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Adult Programs". Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c Potter, Chris (September 16, 2004). "Is it true that the well-known "Mr. Yuk" sticker was created right here in Pittsburgh?". Pittsburgh City Paper. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Fisher, Ken (June 25, 1973). "Yeech! It's Mr. Yuk, He's Poison!". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 15.

- ^ Gaulton, Tom; Wyke, Stacey; Collins, Samuel (2018). Chemical Health Threats: Assessing and Alerting. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 165. ISBN 9781788015523.

- ^ Vernberg K, Culver-Dickinson P, Spyker DA. (1984). "The deterrent effect of poison-warning stickers". American Journal of Diseases of Children 138, 1018–1020. PMID 6496418

- ^ Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Beautrais AL, Shannon FT. (1982). "A controlled field trial of a poisoning prevention method". Pediatrics 69, 515–520. PMID 7079005

- ^ Washington Poison Center Archived 2008-11-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rice, J. Berg (2012). Salvendy, Gavriel (ed.). Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1479. ISBN 9780470528389.

- ^ "Mr. Yuk - Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC". Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Melissa (2013-04-02). "Mr. Yuk: A retired poison prevention icon | Northern New England Poison Center". www.nnepc.org. Retrieved 2024-05-30.

- ^ "Learn About Mr. Yuk from Pittsburgh Poison Center". UPMC | Life Changing Medicine. Retrieved 2024-05-30.