Knock on Any Door is a 1949 American courtroom trial film noir directed by Nicholas Ray and starring Humphrey Bogart. The movie was based on the 1947 novel of the same name by Willard Motley. The picture gave actor John Derek his breakthrough role as young hoodlum Nick Romano, whose motto was "Live fast, die young, and have a good-looking corpse."[2][3]

| Knock on Any Door | |

|---|---|

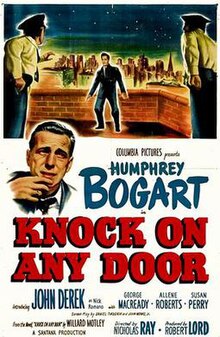

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Nicholas Ray |

| Screenplay by | John Monks Jr. Daniel Taradash |

| Based on | Knock on Any Door (1947 novel) by Willard Motley |

| Produced by | Robert Lord |

| Starring | Humphrey Bogart John Derek George Macready Allene Roberts Susan Perry |

| Cinematography | Burnett Guffey |

| Edited by | Viola Lawrence |

| Music by | George Antheil |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $2.1 million[1] |

Plot

editAgainst the wishes of his law partners, slick talking lawyer Andrew Morton takes the case of Nick Romano, a troubled punk from the slums, partly because he himself came from the same slums and partly because he feels guilty for his partner botching the criminal trial of Nick's father years earlier. Nick is on trial for shooting a policeman point-blank and faces execution if convicted.

Nick's history is presented through flashbacks showing him as a hoodlum committing one petty crime after another. Morton's wife Adele convinces him to play nursemaid to Nick in order to make Nick a better person. Nick then robs Morton of $100 after a fishing trip. Shortly after that, Nick marries Emma, and he tries to change his lifestyle. He takes on job after job but keeps getting fired because of his recalcitrance. He wastes his paycheck playing dice, wanting to buy Emma some jewelry, and then walks out on another job after punching his boss. Feeling a lack of hope of ever being able to live a normal life, Nick decides to return to his old ways, sticking to his motto: "Live fast, die young, and have a good-looking corpse."[3] He abandons Emma, even after she tells him that she is pregnant. After Nick commits a botched hold-up at a train station, he returns to Emma so as to take her with him as he flees. He finds that she had committed suicide by gas from an open oven door.

Morton's strategy in the courtroom is to argue that slums breed criminals and that society is to blame for crimes committed by people who live in such miserable conditions. Morton argues that Romano is a victim of society and not a natural-born killer. However, his strategy does not have the desired effect on the jury, thanks to the badgering of the seasoned and experienced District Attorney Kerman, who delivers question after question until Nick shouts out his admission of guilt. Morton, who is naive to believe in his client's innocence, is shocked by Nick's confession. Nick decides to change his plea to guilty. During the sentencing hearing, Morton manages to arouse some sympathy for the plight of those in a dead-end existence. He pleads that anyone who "knocks on any door" may find a Nick Romano. Nevertheless, Nick is sentenced to die in the electric chair. Morton visits Nick prior to the execution and watches him walk down the hall to the death chamber.

Cast

edit- Humphrey Bogart as Andrew Morton

- John Derek as Nick Romano

- George Macready as Dist. Atty. Kerman

- Allene Roberts as Emma

- Candy Toxton as Adele Morton (credited as Susan Perry)

- Mickey Knox as Vito

- Barry Kelley as Judge Drake

Uncredited

- Cara Williams as Nelly Watkins

- Jimmy Conlin as Kid Fingers

- Sumner Williams as Jimmy

- Sid Melton as "Squint" Zinsky

- Pepe Hern as Juan Rodriguez

- Dewey Martin as Butch

- Davis Roberts as Jim 'Sunshine' Jackson

- Houseley Stevenson as Junior

- Vince Barnett as Bartender

- Thomas Sully as Officer Hawkins

- Florence Auer as Aunt Lena

- Pierre Watkin as Purcell

- Gordon Nelson as Corey

- Argentina Brunetti as Ma Romano

- Dick Sinatra as Julian Romano

- Carol Coombs as Ang Romano

- Joan Baxter as Maria Romano

- Dooley Wilson as Piano player

- Helen Mowery as Miss Holiday

- Chester Conklin as Barber

- George Chandler as Cashier[4]

Production

editKnock on Any Door, based on Willard Motley's 1947 novel of the same name, was Hollywood's second major-studio movie adapted from a novel by an African-American author.[citation needed] (The first was The Foxes of Harrow (1947), adapted from a novel by Frank Yerby.[5])

Producer Mark Hellinger purchased the rights to Motley's novel, and intended Humphrey Bogart and Marlon Brando to star in the production. However, after Hellinger died in late 1947, Robert Lord and Bogart formed a corporation to produce the film: Santana Productions, named after Bogart's private sailing yacht.[6] Jack L. Warner was reportedly furious at this, fearing that other stars would do the same and major studios would lose their power.[citation needed]

In 1958 Motley wrote a sequel novel, Let No Man Write My Epitaph. This book was also filmed, as Let No Man Write My Epitaph (1960), produced and directed by Philip Leacock and starring Burl Ives, Shelley Winters, James Darren, and Ella Fitzgerald, among others.[7]

Reception

editCritical response

editNew York Times film critic Bosley Crowther called the film "a pretentious social melodrama" and blasted the film's message and screenplay. He wrote: "Rubbish! The only shortcoming of society which this film proves is that it casually tolerates the pouring of such fraudulence onto the public mind. Not only are the justifications for the boy's delinquencies inept and superficial, as they are tossed off in the script, but the nature and aspect of the hoodlum are outrageously heroized."[8]

The staff at Variety magazine was more receptive of the film, writing: "An eloquent document on juvenile delinquency, its cause and effect, has been fashioned from Knock on Any Door...Nicholas Ray's direction stresses the realism of the script taken from Willard Motley's novel of the same title, and gives the film a hard, taut pace that compels complete attention."[9]

According to critic Hal Erickson, the oft-repeated credo spoken by the character Nick Romano — "Live fast, die young, and have a good-looking corpse" — would become the "clarion call for a generation of disenfranchised youth."[10]

Filmink wrote it "isn’t the classic its makers were hoping for, but it’s not a bad film and Derek is effective enough."[11]

References

edit- ^ "Top Grossers of 1949". Variety. 4 January 1950. p. 59.

- ^ Slide, Anthony. Lost Gay Novels: A Reference Guide to Fifty Works from the First Half of the Twentieth Century, pages 135-136, 1st edition, 2003. Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press. ISBN 1-56023-413-X.

- ^ a b Nicholas Ray (1949). Knock on Any Door. Event occurs at 32m and 61m.

- ^ McCarty, Clifford (1966). Bogey - The Films of Humphrey Bogart (1st ed.). New York, N.Y.: Cadillac Publishing Co., Inc. p. 147.

- ^ Frank Miller. "The Foxes of Harrow (review)". TCM.

When Fox bought the screen rights, [Yerby] also became the first African-American to sell a novel to a major Hollywood studio.

- ^ Silver, Alain, and Elizabeth Ward, eds. Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style; film noir synopsis and analysis of Knock on Any Door by Blake Lucas and Alain Silver, page 162, 3rd edition, 1992. Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-479-5.

- ^ Let No Man Write My Epitaph at IMDb

- ^ Crowther, Bosley. The New York Times, film review, January 23, 1949. Last accessed: December 9, 2007.

- ^ Variety, film review, January 1, 1949. Last accessed: December 9, 2007.

- ^ Knock on Any Door at AllMovie.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (5 November 2024). "The Cinema of John Derek, Movie Star". Filmink. Retrieved 5 November 2024.