On 12 February 1993 in Merseyside, two 10-year-old boys, Robert Thompson and Jon Venables, abducted, tortured, and murdered a two-year-old boy, James Patrick Bulger (16 March 1990[2] – 12 February 1993).[3][4] Thompson and Venables led Bulger away from the New Strand Shopping Centre in Bootle, after his mother had taken her eyes off him momentarily. His mutilated body was found on a railway line two and a half miles (four kilometres) away in Walton, Liverpool, two days later.

| Murder of James Bulger | |

|---|---|

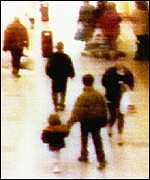

Bulger being abducted by Thompson (in front of Bulger) and Venables (holding Bulger's hand) in an image captured on shopping centre CCTV | |

| Location | Walton, Liverpool, England |

| Date | 12 February 1993 |

Attack type | Child-on-child murder by bludgeoning, torture murder, kidnapping, mutilation, dismemberment |

| Weapons | Bricks, stones, a fishplate, others |

| Victim | James Patrick Bulger, aged 2 |

| Burial | Kirkdale Cemetery, Fazakerley, Liverpool[1] |

| Perpetrators |

|

| Motive | Inconclusive |

| Verdict | Guilty |

| Convictions | Murder, abduction |

| Sentence | Indefinite sentence in juvenile detention (paroled after 8 years) |

Thompson and Venables were charged on 20 February 1993 with abduction and murder. They were found guilty on 24 November, making them the youngest convicted murderers in modern British history. They were sentenced to indefinite detention at Her Majesty's pleasure, and remained in custody until a Parole Board decision in June 2001 recommended their release on a lifelong licence at age 18.[5] Venables was sent to prison in 2010 for breaching the terms of his licence, was released on parole again in 2013, and in November 2017 was again sent to prison for possessing child sexual abuse images on his computer. He remained in prison in 2023 after his appeals for parole were rejected.

The Bulger case has prompted widespread debate about how to handle young offenders when they are sentenced or released from custody.[6][7]

Timeline

editPrior to the kidnapping

editClosed-circuit television (CCTV) at the New Strand Shopping Centre in Bootle on 12 February 1993 showed Thompson and Venables casually observing children, apparently selecting a target.[8] The boys were playing truant from their local primary school, which they did regularly.[9] Throughout the day, Thompson and Venables were seen shoplifting various items, including sweets, batteries, a troll doll, and a can of blue Humbrol modelling paint.[10] One of the boys later said that before abducting Bulger, they were planning to abduct a child, lead him to the busy road alongside the shopping centre, and push him into the oncoming traffic.[11]

Abduction

editThat same afternoon, two-year-old James Patrick Bulger, from Kirkby, went with his mother, Denise, to the New Strand Shopping Centre. While inside the A.R. Tym's butcher's shop on the lower floor of the centre at around 15:40, Denise, who had let go of her son's hand to pay for her shopping, realised that her son was missing.[4][12] Thompson and Venables had approached Bulger, took him by the hand, and led him out of the shopping centre.[13][14] The moment was caught on CCTV at 15:42.[15][16]

Torture and murder

editThompson and Venables took Bulger to the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, around 1⁄4 mile (400 metres) from the New Strand Shopping Centre, where they dropped him on his head, and he suffered injuries to his face. The boys joked about pushing Bulger into the canal.[9][17] An eyewitness said that when he saw Bulger at the canal, the boy was "crying his eyes out".[18] The boys went on a 2+1⁄2-mile (4-kilometre) walk across Liverpool; they were seen by around 38 people, but most bystanders did nothing to intervene.[18][19] Two people confronted Thompson and Venables, but they either claimed that Bulger was their brother, or that he was lost, and that they were taking him to a police station.[20] At one point, the boys took Bulger into a pet shop, from which they were ejected.[21]

Eventually, the boys arrived in Walton. With Walton Lane Police Station across the road, they hesitated, then led Bulger up a steep bank to a railway line near the former Walton & Anfield railway station, close to Walton Park Cemetery.[9] One of the boys threw the blue paint that they had shoplifted earlier into Bulger's left eye.[22] They kicked him, stamped on him, and threw bricks and stones at him. They placed batteries in Bulger's mouth[23] and may have inserted some into his anus, although none were found there.[4] Finally, the boys dropped a 10 kg (22 lb) railway fishplate on Bulger.[24][25][26] He sustained 10 skull fractures as a result of the bar striking his head. Pathologist Alan Williams stated that Bulger suffered so many injuries—42 in total—that none could be identified as the fatal blow.[27]

Thompson and Venables laid Bulger across the railway tracks and weighted his head down with rubble, hoping that a train would hit him and his death would be ruled an accident. After they left the scene, his body was cut in half by a train.[28] Bulger's severed body was discovered by four boys two days later.[29][9][30] A forensic pathologist testified that Bulger died before he was struck by the train.[28]

Investigation

editPolice suspected that the boys had sexually assaulted Bulger, as his shoes, socks, trousers, and underpants had been removed. The pathologist's report, which was read out in court, found that Bulger's foreskin had been forcibly pulled back.[24][31] When Thompson and Venables were questioned about this aspect of the attack by detectives and a child psychiatrist, Eileen Vizard, the pair were reluctant to give details.[4][21][32] When Venables was let out on parole, his psychiatrist, Susan Bailey, reported that "visiting and revisiting the issue with Jon as a child, and now as an adolescent, he gives no account of any sexual element to the offence."[4]

The police quickly found low-resolution video images of two unidentified boys abducting Bulger from the New Strand Shopping Centre.[9] The railway embankment upon which his body had been discovered was soon adorned with hundreds of bunches of flowers.[33] The family of one boy, who was detained for questioning but subsequently released, had to flee the city due to threats from vigilantes. The breakthrough came when a woman, upon seeing slightly enhanced images of the two boys on national television, recognised Venables, and remembered seeing him playing truant with Thompson in the Bootle area that day. She contacted the police, and the boys were arrested.[30]

Legal proceedings

editArrest

editThe fact that the suspects were so young came as a shock to investigating officers, headed by Detective Superintendent Albert Kirby of Merseyside Police. Early press reports and police statements had referred to Bulger being seen with "two youths" (suggesting that the killers were teenagers), the ages of the boys being difficult to ascertain from the images captured by CCTV.[30] Forensic tests confirmed that both boys had the same blue paint on their clothing as found on Bulger's body. Both had blood on their shoes; the blood on Thompson's shoe was matched to Bulger's through DNA tests. A pattern of bruising on Bulger's right cheek matched the features of the upper part of a shoe worn by Thompson; a paint mark in the toecap of one of Venables's shoes indicated he must have used "some force" when he kicked Bulger.[34] Thompson is said to have asked police whether Bulger had been taken to hospital to "get him alive again."[35]

The boys were each charged with the murder of James Bulger on 20 February 1993,[9] and appeared at South Sefton Youth Court on 22 February 1993, where they were remanded in custody to await trial.[10][23] In the aftermath of their arrest, and throughout the media accounts of their trial, the boys were referred to as "Child A" (Thompson) and "Child B" (Venables).[2] Awaiting trial, they were held in the secure units where they would eventually be sentenced to be detained at Her Majesty's pleasure.[4]

Trial

editUp to 500 protesters gathered at the Magistrates' Court in the Metropolitan Borough of Sefton during the boys' initial court appearances. The parents of the accused were moved to different parts of the country and assumed new identities following death threats from vigilantes.[30] The full trial opened at Sessions House, Preston, on 1 November 1993,[9] conducted as an adult trial with the accused in the dock away from their parents, and the judge and court officials in legal regalia.[36] The boys denied the charges of murder, abduction and attempted abduction.[34] The attempted abduction charge related to an incident at the New Strand Shopping Centre earlier on 12 February 1993, the day of Bulger's death. Thompson and Venables had attempted to lead away another two-year-old boy, but had been prevented by the boy's mother.[14]

Each boy sat in view of the court on raised chairs so they could see out of the dock designed for adults, and were accompanied by two social workers and guards. Although they were separated from their parents, they were within touching distance when their families attended the trial. News stories reported the demeanour of the defendants.[37] These aspects were later criticised by the European Court of Human Rights, which ruled in 1999 that they had not received a fair trial by being tried in public in an adult court.[9] At the trial, the lead prosecution counsel Richard Henriques successfully rebutted the principle of doli incapax, which presumes that young children cannot be held legally responsible for their actions.[38]

Thompson and Venables were considered by the court to be capable of "mischievous discretion", meaning an ability to act with criminal intent as they were mature enough to understand that they were doing something seriously wrong.[39] A child psychiatrist, Eileen Vizard, who interviewed Thompson before the trial, was asked in court whether he would know the difference between right and wrong, that it was wrong to take a young child away from his mother, and that it was wrong to cause injury to a child. Vizard replied, "If the issue is on the balance of probabilities, I think I can answer with certainty." Vizard also said that Thompson was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder after the attack on Bulger.[40] Susan Bailey, the Home Office's forensic psychiatrist who interviewed Venables, said unequivocally that he knew the difference between right and wrong.[41]

Thompson and Venables did not speak during the trial, and the case against them was based to a large extent on the more than 20 hours of tape-recorded police interviews with the boys, which were played back in court.[38] Thompson was considered to have taken the leading role in the abduction process, though it was Venables who had apparently initiated the idea of taking Bulger to the railway line. Venables later described how Bulger seemed to like him, holding his hand and allowing him to pick him up on the meandering journey to the scene of his murder.[4] Laurence Lee, who was the solicitor of Venables during the trial, later said that Thompson was one of the most frightening children he had seen, and compared him to the Pied Piper.[42] After his appearances in court, Venables would strip off his clothes, saying: "I can smell James like a baby smell."[35] The prosecution admitted a number of exhibits during the trial, including a box of 27 bricks, a blood-stained stone, Bulger's underpants, and the rusty iron bar described as a railway fishplate. The pathologist spent 33 minutes outlining the injuries sustained by Bulger; many of those to his legs had been inflicted after he was stripped from the waist down. Brain damage was extensive and included a haemorrhage.[43]

The boys, by then aged 11, were found guilty of Bulger's murder at the Preston court on 24 November 1993, becoming the youngest convicted murderers of the 20th century.[44] The judge, Mr Justice Morland, told Thompson and Venables that they had committed a crime of "unparalleled evil and barbarity ... In my judgment, your conduct was both cunning and very wicked."[45] Morland sentenced them to be detained at Her Majesty's pleasure, with a recommendation that they should be kept in custody for "very, very many years to come", recommending a minimum term of eight years.[9] At the close of the trial, the judge lifted reporting restrictions and allowed the names of the killers to be released, saying: "I did this because the public interest overrode the interest of the defendants ... There was a need for an informed public debate on crimes committed by young children."[46] David Omand later criticised this decision and outlined the difficulties created by it in his 2010 review of the probation service's handling of the case.[47]

Post-trial

editShortly after the trial, and after the judge had recommended a minimum sentence of eight years, Lord Taylor of Gosforth, the Lord Chief Justice, recommended that the two boys should serve a minimum of ten years,[9] which would have made them eligible for release in February 2003 at the age of 20. The editors of The Sun handed a petition bearing nearly 280,000 signatures to Michael Howard, the Home Secretary, in a bid to increase the time spent by both boys in custody.[48] This campaign was successful, and Howard announced in July 1994 that the boys would be kept in custody for a minimum of fifteen years,[48][49] meaning that they would not be considered for release until February 2008, by which time they would be 25 years old.[9]

Lord Donaldson criticised Howard's intervention, describing the increased tariff as "institutionalised vengeance ... [by] a politician playing to the gallery".[9] The increased minimum term was overturned in 1997 by the House of Lords that ruled it "unlawful" for the Home Secretary to decide on minimum sentences for young offenders.[50] The High Court of Justice and European Court of Human Rights have since ruled that although the parliament may set minimum and maximum terms for individual categories of crime, it is the responsibility of the trial judge, with the benefit of all the evidence and argument from both prosecution and defence counsel, to determine the minimum term in individual criminal cases.[49]

Tony Blair, then Shadow Home Secretary, gave a speech in Wellingborough during which he said: "We hear of crimes so horrific they provoke anger and disbelief in equal proportions ... These are the ugly manifestations of a society that is becoming unworthy of that name."[9] Prime Minister John Major said that "society needs to condemn a little more, and understand a little less."[9] The trial judge Mr Justice Morland stated that exposure to violent videos might have encouraged the actions of Thompson and Venables; this was disputed by David Maclean, the Minister of State at the Home Office at the time, who said that police had found no evidence linking the case with "video nasties".[51]

Some British tabloid newspapers claimed that the attack on Bulger was inspired by the film Child's Play 3, and campaigned for the rules on "video nasties" to be tightened.[52] During the police investigation, it emerged that Child's Play 3 was one of the films that Venables' father had rented in the months prior to the killing, but it was not established that Venables had ever watched it.[53][54] One scene in the film shows the malevolent doll Chucky being splashed with blue paint during a paintball game. A Merseyside detective said, "We went through something like 200 titles rented by the Venables family. There were some you or I wouldn't want to see, but nothing—no scene, or plot, or dialogue—where you could put your finger on the freeze button and say that influenced a boy to go out and commit murder."[51] Inspector Ray Simpson of Merseyside Police commented: "If you are going to link this murder to a film, you might as well link it to The Railway Children."[55] The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 clarified the rules on the availability of certain types of video material to children.[9][56]

Detention

editFollowing the trial, Thompson was detained at Barton Moss Secure Children's Home, which was then known as Barton Moss Secure Care Centre,[57] in Salford.

Venables was detained in Vardy House, a small eight-bedded unit at Red Bank Secure Unit in St. Helens on Merseyside. These locations were not publicly known until after the boys' release.[4] Details of the boys' lives were recorded twice daily on running sheets and signed by the member of staff who had written them; the records were stored at the units and copied to officials in Whitehall. The boys were taught to conceal their real names and the crime they had committed which resulted in their being in the units. Venables' parents regularly visited their son at Red Bank, just as Thompson's mother did, every three days, at Barton Moss.[4] The boys received education and rehabilitation; despite initial problems, Venables was said to have eventually made good progress at Red Bank, resulting in him being kept there for the full eight years, despite the facility only being a short-stay remand unit.[4] Both boys were reported to suffer post-traumatic stress disorder, and Venables in particular told of experiencing nightmares and flashbacks of the murder.[4]

Appeal and release

editIn 1999, lawyers for Thompson and Venables appealed to the European Court of Human Rights that the boys' trial had not been impartial, since they were too young to follow proceedings and understand an adult court. The court dismissed their claim that the trial was inhuman and degrading treatment but upheld their claim they were denied a fair trial by the nature of the court proceedings.[58][59][60] The court also held that the Home Secretary's intervention had led to a "highly charged atmosphere", which resulted in an unfair judgment.[61] On 15 March 1999, the court in Strasbourg ruled by 14 votes to five that there had been a violation of Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights; regarding the fairness of the trial of Thompson and Venables, they stated: "The public trial process in an adult court must be regarded in the case of an 11 year-old child as a severely intimidating procedure."[36]

In September 1999, Bulger's parents appealed to the European Court of Human Rights but failed to persuade the court that a victim of a crime has the right to be involved in determining the sentence of the perpetrator.[9][62] The European Court case led to the new Lord Chief Justice, Harry Woolf, reviewing the minimum sentence. In October 2000, he recommended the tariff be reduced from ten to eight years,[9] adding that Her Majesty's Young Offender Institution was a "corrosive atmosphere" for the juveniles.[63]

In June 2001, after a six-month review, the parole board ruled the boys were no longer a threat to public safety and could be released, as their minimum tariff had expired in February of that year. Home Secretary David Blunkett approved the decision, and they were released a few weeks later on lifelong licence after serving eight years.[64][65] It was reported that both boys "were given new identities and moved to secret locations under a 'witness protection'-like programme."[66] This was supported by the fabrication of passports, national insurance numbers, qualification certificates, and medical records. Blunkett added his own conditions to their licence and insisted on being sent daily updates on the boys' actions.[4]

The terms of their release included the following: They were not allowed to contact each other or Bulger's family; they were prohibited from visiting the Merseyside region;[67] curfews may be imposed on them, and they must report to probation officers. If they breached the rules or were deemed a risk to the public, they could be returned to prison.[68]

A court injunction was imposed on the media after the trial, preventing the publication of details about Thompson and Venables. The worldwide injunction was kept in force following their release on parole, so their new identities and locations could not be published.[9][69][70] In 2001, Blunkett stated: "The injunction was granted because there was a real and strong possibility that their lives would be at risk if their identities became known."[68]

Later developments

editDissolution of James Bulger's family

editIn the months after the trial, and following the birth of their second son, the marriage of Bulger's parents, Ralph and Denise, broke down; they divorced in 1995.[71]

Denise Bulger later married Stuart Fergus, with whom she had two sons.[72] Ralph Bulger also remarried, and had three daughters with his second wife.[73][74]

Bulger memorial and legal activism

editOn 14 March 2008, an appeal to set up a Red Balloon Learner Centre in Merseyside in memory of James Bulger was launched by his mother and Esther Rantzen.[75][76] A memorial garden in Bulger's memory was created in Sacred Heart Primary School in his hometown of Kirkby, the school he would have been expected to attend had he not been murdered.[9]

In March 2010, a call was made by England's Children's commissioner Maggie Atkinson to raise the age of criminal responsibility from ten to twelve. She said that the killers of James Bulger should have undergone "programmes" to help turn their lives around, rather than being prosecuted. The Ministry of Justice rejected the call, saying that children over the age of ten knew the difference "between bad behaviour and serious wrongdoing".[77]

Court protective injunction and violations

editDuring Venables' and Thompson's incarcerations, the court order protecting their identities was renewed, but details about them, both real and fabricated, gradually leaked into the press and via the internet.

Early reports about prison life

editThe Observer revealed that both Venables and Thompson had passed their GCSEs and A-Levels during their sentences. The paper also stated that the Bulger family's lawyers had consulted psychiatric experts in order to present the parole panel with a report that suggested Thompson is an undiagnosed psychopath, citing his lack of remorse during his trial and arrest. That report was ultimately dismissed; however, Thompson's lack of remorse at the time, in stark contrast to Venables, led to considerable scrutiny from the parole panel. Upon release, both Thompson and Venables had lost all trace of their Scouse accent.[78]

In a psychiatric report prepared in 2000 before Venables' release, he was described as posing a "trivial" risk to the public and unlikely to reoffend. The chances of his successful rehabilitation were described as "very high".[79]

The Manchester Evening News published details that suggested the names of the secure institutions in which the pair were housed, in breach of the injunction against publicity that had been renewed early in 2001. In December that year, the paper was fined £30,000 for contempt of court and ordered to pay costs of £120,000.[80] No significant publication or vigilante action against Thompson or Venables has occurred. Despite this, Bulger's mother, Denise, told how in 2004 she received a tip-off from an anonymous source that helped her locate Thompson. Upon seeing him, she was "paralysed with hatred", and was unable to confront him.[81]

In April 2007, documents released under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 confirmed that the Home Office had spent £13,000 on an injunction to prevent a foreign magazine from revealing the new identities of Thompson and Venables.[82][83]

False identification and internet trolling

editIn April 2010, a 19-year-old man from the Isle of Man was given a three-month suspended prison sentence for falsely claiming in a Facebook message that one of his former colleagues was Thompson. In passing sentence, Deputy High Bailiff Alastair Montgomerie said that the teenager had "put that person at significant risk of serious harm" and in a "perilous position" by making the allegation.[84]

In March 2012, a 26-year-old man from Chorley, Lancashire, was arrested after allegedly setting up a Facebook group with the title "What happened to Jamie Bulger was fucking hilarious". The man's computer was seized for further investigations.[85]

Internet photo posts

editOn 25 February 2013, the Attorney General's Office announced that it was instituting contempt of court proceedings against several people who had allegedly published photographs online showing Thompson or Venables as adults.[86] A spokesman commented:

- "There are many different images circulating online claiming to be of Venables or Thompson; potentially innocent individuals may be wrongly identified as being one of the two men and placed in danger. The order, and its enforcement, is therefore intended to protect not only Venables and Thompson, but also those members of the public who have been incorrectly identified as being one of the two men."[87]

On 26 April 2013, two men received suspended jail sentences of nine months after admitting to contempt of court, by publishing photographs that they claimed to be of Venables and Thompson on Facebook and Twitter. The posts were seen by 24,000 people. According to BBC legal correspondent Clive Coleman, the purpose of the prosecution was to ensure that the public was aware that Internet users were also subject to the law of contempt.[88]

On 27 November 2013, a man from Liverpool received a 14-month suspended prison sentence for posting images on Twitter claiming to show Venables.[89]

On 31 January 2019, a man and a woman pleaded guilty to eight contempt-of-court offences at the High Court after they admitted to posting photos on social media that they claimed identified Venables; both received suspended prison sentences.[90] In March 2019, actress Tina Malone was given an eight-month suspended prison sentence for posting Venables' alleged identity on Facebook.[91]

In January 2020, a 53-year-old woman from Ammanford in South Wales received a prison sentence of eight months, suspended for 15 months: in November 2017, she had published an alleged photograph of Venables on Facebook, with the advice "share this as much as possible". Lord Justice Nigel Davis said that the offence was "close to the line" for an immediate prison sentence, but suspended the sentence after observing an early admission of guilt and remorse by the woman.[92]

Trolling and stalking of James' mother

editOn 14 July 2016, a woman from Margate in Kent was jailed for three years after sending Twitter messages to Bulger's mother, in which she posed as one of his killers, and as Bulger's ghost.[93] The sentence was reduced to 2+1⁄2 years on appeal.[94]

On 25 October 2016, a man was jailed for 26 weeks for stalking Denise Fergus; he had previously received a police warning for stalking her in 2008.[95]

Later life of Jon Venables

editRelationships

editShortly before his 2001 release, when aged 17, Venables was alleged to have had sex with a woman who worked at the Red Bank secure unit where he was held. In April 2011, in the aftermath of his 2010 imprisonment, these allegations were outlined in a Sunday Times Magazine article written by David James Smith, who had been following the Bulger case since the 1993 trial, and again later in a BBC documentary titled Jon Venables: What went wrong? The female staff member was suspended for sexual misconduct; she never returned to work at Red Bank.[4][96] A spokesman for St Helens Council denied that the incident had been covered up, saying, "All allegations were thoroughly investigated by an independent team on the orders of the Home Office and chaired by Arthur de Frischling, a retired prison governor."[97]

Misdemeanours while on release 2002–2008

editVenables began living independently in March 2002. Some time thereafter, he began a relationship with a woman who had a five-year-old child; it is not known whether Venables had already begun downloading child abuse images at the time of dating the woman, although he denies having ever met the child.[4]

After a period of apparently reduced supervision, Venables began excessively drinking, taking drugs, and downloading child abuse images, as well as visiting Merseyside, which was a breach of his licence. In September 2002, Venables was arrested on suspicion of affray, following a fight outside a nightclub; he claimed he was acting in self-defence, and the charges were later dropped after he agreed to go on an alcohol-awareness course. Three months later, he was found to be in possession of cocaine; he was subjected to a curfew.[4]

In 2005, when Venables was age 23, his probation officer met another girlfriend of his, who was aged 17. After a number of "young girlfriends", it was presumed that Venables was having a delayed adolescence.[4] In 2008, a new probation officer said that Venables spent "a great deal of leisure time" playing video games and on the Internet.[citation needed]

On two occasions, Jon Venables revealed his true identity to a friend.[7][failed verification]

2010 imprisonment

editVenables contacted his probation officer in February 2010, reporting that he feared that his new identity had been compromised at his place of work. When the officer arrived at his flat, Venables was attempting to remove or destroy the hard drive of his computer with a knife and a tin opener.[4] The officer's suspicions were aroused, and the computer was taken away for examination leading to the discovery of the child sexual abuse material, which included children as young as two being raped by adults,[98][99] and penetrative rape of seven- or eight-year-olds.[4]

On 2 March 2010, the Ministry of Justice revealed that Venables had been returned to prison for an unspecified violation of the terms of his licence of release. Justice Secretary Jack Straw stated that Venables had been returned to prison because of "extremely serious allegations", and stated that he was "unable to give further details of the reasons for Jon Venables' return to custody, because it was not in the public interest to do so".[100] On 7 March, media reports said that he had been accused of offences related to possession of child sexual abuse material.[101][102][103]

In a statement to the House of Commons on 8 March 2010, Straw reiterated that it was "not in the interest of justice" to reveal the reason why Venables had been returned to custody.[104] Baroness Butler-Sloss, the judge who made the decision to grant Venables anonymity in 2001, warned that Venables could be killed if his identity was revealed.[105]

Bulger's mother, Denise Fergus, said she was angry that the parole board did not tell her that Venables had been returned to prison, and called for his anonymity to be removed if he was charged with a crime.[106] A spokesperson for the Ministry of Justice stated that there was a worldwide injunction against publication of either killer's location or new identity.[107] Venables' return to prison revived a false claim that a man from Fleetwood, Lancashire, was Venables. While the claim was reported and dismissed in September 2005,[108] it reappeared in March 2010 when it was circulated widely via SMS messages and Facebook.[109] Chief Inspector Tracie O'Gara of Lancashire Constabulary stated: "An individual who was targeted four-and-a-half years ago was not Jon Venables, and now he has left the area."[110][111]

On 21 June 2010, Venables was charged with possession and distribution of indecent images of children. It was alleged that he had downloaded 57 indecent images of children over a 12-month period to February 2010, and had allowed other people to access the files through a peer-to-peer network. Venables faced two charges under the Protection of Children Act 1978.[112][113] On 23 July, Venables appeared at a court hearing at the Old Bailey via a video link, visible only to the judge hearing the case.[114] He pleaded guilty to charges of downloading and distributing child sexual abuse material, and was sentenced to two years' imprisonment.[115] At the court hearing, it emerged that Venables had posed in online chat rooms as 35-year-old Dawn "Dawnie" Smith, a supposedly married woman from Liverpool, who boasted about abusing her 8-year-old daughter, in the hope of obtaining further child sexual abuse material.[citation needed]

The judge, Mr. Justice David Bean, ruled that Venables' new identity could not be revealed, but the media were allowed to report that he had been living in Cheshire at the time of his arrest.[116][117] The High Court also heard that Venables had been arrested on suspicion of affray in September 2008, following a drunken street fight with another man. Late that year, he was cautioned for possession of cocaine.[118] In November 2010, a review of the National Probation Service handling of the case by David Omand found that probation officers could not have prevented Venables from downloading child sexual abuse material. Harry Fletcher, the assistant general secretary of the National Association of Probation Officers, said that only 24 hour surveillance would have stopped Venables.[47][119] Venables was eligible for parole in July 2011. On 27 June 2011, the parole board decided that he would remain in custody, and that his parole would not be considered again for at least another year.[120]

New identity 2011

editOn 4 May 2011, it was reported that Venables would once again be given a new identity, following what was described as a "serious security breach", which revealed an identity that he had been using before his imprisonment in 2010; details of the breach could not be reported for legal reasons.[121] A spokesman for the Ministry of Justice commented: "Such a change of identity is extremely rare, and granted only when the police assess that there is clear and credible evidence of a sustained threat to the offender's life on release into the community."[122] The incident occurred after a man from Exeter posted photographs on a website devoted to identifying paedophiles, allegedly showing Venables as an adult, and revealing his name.[123]

2013 parole hearing and release

editIn November 2011, it was reported that officials had decided that Venables would stay in prison for the foreseeable future, as he would be likely to reveal his true identity if released. A Ministry of Justice spokesman declined to comment on the reports.[124] On 4 July 2013, it was reported that the Parole Board for England and Wales had approved the release again of Venables.[125][126] On 3 September 2013, it was reported that Venables had been released from prison.[127]

2017 imprisonment

editOn 23 November 2017, it was reported that Venables had again been recalled to prison for possession of more child sexual abuse imagery. The Ministry of Justice declined to comment on the reports.[128] On 5 January 2018, Venables was charged with unspecified offences relating to indecent images of children.[129] On 7 February 2018, Venables pleaded guilty to possession of indecent images of children for a second time. He pleaded guilty via video link to three charges of making indecent images of children, and one of possessing a "paedophile manual", that included advice for would-be child molesters, including instructions on child grooming and evading detection.[130] He admitted being in possession of 392 category A, 148 category B, and 630 category C child sexual abuse images, and was sentenced to three years and four months in prison. In September 2020, he was denied parole.[131] On 13 December 2023, Venables was again denied parole, with the Parole Board saying that "The panel was not satisfied that release at this point would be safe for the protection of the public."[132]

2019 legal challenge to lift anonymity refused

editOn 4 March 2019, Bulger's father, Ralph, lost a legal challenge to lift the lifelong order protecting Venables' anonymity. Judge Andrew McFarlane turned down the request, saying that the "uniquely notorious" nature of the case meant there is "a strong possibility, if not a probability, that if his identity were known, he would be pursued, resulting in grave and possibly fatal consequences."[133]

Potential overseas resettlement

editIn late June 2019, it was reported that British officials had considered resettling Venables in Canada, Australia, or New Zealand, due to the high costs behind protecting his anonymity. British authorities had reportedly spent £65,000 in legal fees to keep Venables' identity a secret.[134][135] In response to media coverage, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern remarked that, due to his criminal history, Venables would need an exemption under New Zealand's Immigration Act 2009, and that he should "not bother" applying.[136][137]

In popular culture

editFringe 2001 stage play The Age of Consent

editIn August 2001, a stage play titled The Age of Consent by Peter Morris was performed at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. The play featured an 18-year-old character called Timmy, who was due to be released from a secure unit after luring a toddler away from his mother and beating him to death.

The play generated controversy due to the similarities between the character and James' killers.[138] Although she had not seen the play, Denise Fergus denounced it as a work that was "just designed to try and shock people and grab publicity" and that "anyone who would stoop so low as to use my son's death as a subject for comedy is sick and pathetic."[139]

In response to the controversy, Morris stated that the humour in his play was "never at the expense of the various people, Mrs Fergus included, who have suffered so much in the aftermath of James's murder". He commented that the work "is emphatically not a comedy" but instead "intended as a serious moral examination of what contemporary society is doing to children".[140]

Computer game

editIn June 2007, a computer game based on the television series Law & Order, titled Law & Order: Double or Nothing (made in 2003), was withdrawn from stores in the UK following reports that it contained an image of Bulger. The image in question is the CCTV frame of Bulger being led away by Thompson and Venables. The scene in the game involves a computer-generated detective pointing out the picture, which is meant to represent a fictional child abduction that the player is then asked to investigate. Bulger's family, along with many others, complained, and the game was subsequently withdrawn by its UK distributor, GSP.

The game's developer, Legacy Interactive, released a statement in which it apologised for the image's inclusion in the game; according to the statement, the image's use was "inadvertent", and took place "without any knowledge of the crime, which occurred in the UK, and was minimally publicised in the United States".[141]

2008 'true crime'-style stage play

editIn 2008, Swedish playwright Niklas Rådström used the interview transcripts from interrogations with the murderers and their families to recreate the story. His play, Monsters, opened to mixed reviews at the Arcola Theatre in London in May 2009.[142][143]

Australian television publicity stunt

editIn August 2009, Australia's Seven Network used real footage of James Bulger's abduction to promote its crime drama City Homicide. The use of the footage was criticised by Bulger's mother, and Seven apologised.[144]

On 24 August, co-hosts on Seven's breakfast show Sunrise asked whether the killers were now living in Australia, in an apparent tie-in with that week's episode of City Homicide. They answered the question the next day by relaying the Australian government's denial that the killers had been settled in the country.[145]

Soap opera storyline

editA storyline in the British soap opera Hollyoaks was set to begin in December 2009, but cancelled after the series makers gave Bulger's mother Denise Fergus a private screening.

The storyline was to feature Loretta Jones and her friend Chrissy, who had been given new identities before arriving in the village, after being convicted of murdering a child at the age of 12.[146]

Scholarly reference

editIn 2010 the critical theorist Terry Eagleton introduced his book On Evil with the story of Bulger's murder.[147]

Playground (2016 film)

editPlac Zabaw (also known as Playground) is a 2016 Polish drama thriller directed by Bartosz M. Kowalski. The story includes Thompson and Venables, but presented as "Szymek" and "Czarek". The case is used at the end of the film, as both boys abduct a little boy from a mall, taking him to a railroad, abusing and murdering him.

2019 Oscars controversy

editIn January 2019, the short film Detainment was nominated for Best Live Action Short Film at the 91st Academy Awards ("The Oscars"). The film is based on transcripts of the police interviews with Thompson and Venables after their arrests.[148][149] Bulger's mother was not consulted before the film's release. She criticised its nomination and circulated a petition to have the film removed from the nominations.[150] In response, the film's director Vincent Lambe refused to withdraw the film from consideration, saying that "it would defeat the purpose of making the film".[151]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Paterson, Stewart (26 November 2017). "James Bulger's father demands son's killer Jon Venables is stripped of anonymity". Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2020 – via www.nzherald.co.nz.

- ^ a b "The killers and the victims". CNN. 22 June 2001. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Thompson & Venables Recommendations as to Tariffs to the Secretary of State for Home Affairs". 26 October 2000. Archived from the original on 26 December 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Smith, David James (3 April 2011). "The Secret Life of a Killer" (PDF). The Sunday Times Magazine: 22–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2013.

- ^ "Bulger killers to be released on parole". The Independent. 22 June 2001. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ Firth, Paul (3 March 2010). "A question of release and redemption as Bulger killer goes back into custody". Yorkshire Post. Johnston Press. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ a b "UPRN Entry for Barton Moss". Ordinance Survey Find My Address. 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Bulger killers eligible for release". BBC. 26 October 2000. Archived from the original on 24 December 2002. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Davenport-Hines, Richard (2004). "Bulger James Patrick (1990–1993), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/76074. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2009. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (Subscription Required)

- ^ a b Scott, Shirley (29 August 2009). "Death of James Bulger: Pt 1, The Video Tape". truTV.com. Archived from the original on 21 January 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ Blease, Stephen (23 February 2009). "Young know what is wrong". North-West Evening Mail. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ Sharratt, Tom (2 November 1993). "James Bulger 'battered with bricks'". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ McKay, Mike (26 October 2000). "Every parent's nightmare". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ a b Scott, Shirley. "Death of James Bulger: Pt 2, Abduction". truTV.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ "CCTV: Does it work?". BBC. 13 August 2002. Archived from the original on 31 July 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Uncropped Mothercare CCTV still of the abduction, showing the timestamp at 15:42:32". Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ Scott, Shirley. "Death of James Bulger: Pt 3, The Trial". truTV. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ a b Pilkington, Edward (5 November 1993). "James Bulger in distress, say passers-by". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016.

- ^ "Schoolboy tells of James Bulger's tears: Children said murder case victim was a brother, court told". The Independent. London. 9 November 1993. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Coslett, Paul (4 December 2006). "Murder of James Bulger". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 June 2009.

- ^ a b Scott, Shirley (29 August 2009). "Death of James Bulger: Pt 6, The Trial". truTV.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ Ferguson, Euan (9 February 2003). "Ten years on". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017.

- ^ a b Mikkelson, Barbara (21 July 2001). "Murder of Jamie Bulger". Snopes.com. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ a b Foster, Jonathan (10 November 1993). "James Bulger suffered multiple fractures: Pathologist reveals two-year-old had 42 injuries including fractured skull". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ Sharratt, Tom (2 November 1993). "James Bulger murder". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013.

- ^ Coslett, Paul (25 November 1993). "Lessons of an avoidable tragedy". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017.

- ^ Foster, Jonathan (10 November 1993). "James Bulger suffered multiple fractures: Pathologist reveals two-year-old had 42 injuries including fractured skull. Jonathan Foster reports". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on 29 August 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- ^ a b Sharratt, Tom (2 November 1993). "James Bulger 'battered with bricks'". Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Docking, Neil (17 May 2017). "Drug dealer who found James Bulger's body jailed after crashing into family's car". Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d Scott, Shirley (29 August 2009). "Death of James Bulger: Pt 4, Ten-Year-Old Suspects". truTV.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ Sereny, Gitta (6 February 1994). "Re-examining the evidence". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ Scott, Shirley. "Death of James Bulger: Pt 5, Robert Denies, Jon Cries". truTV.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ Schmidt, William E. (24 February 1993). "Liverpool Tries to Reconcile Murder and a Boy Next Door". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017.

- ^ a b Pilkington, Edward (11 November 1993). "Blood on boy's shoe 'was from victim'". Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ a b Lusher, Adam (14 November 2018). "James Bulger documentary: Jon Venables so haunted by toddler victim he detected 'baby smell' on everything he wore, C5 show claims". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Young suspects 'intimidated' by trial". BBC News. 15 March 1999. Archived from the original on 7 July 2003. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ Harris, Paul; Bright, Martin (24 June 2001). "The secret meetings that set James's killers free". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013.

- ^ a b Foster, Jonathan (17 December 1999). "Bulger ruling: If the defendants could not talk about their crime, how could they conduct a defence?". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ Morrison, Blake (11 April 2009). "Let the circus begin". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Gillan, Audrey (17 December 1999). "Fear and trauma in courtroom". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Foster, Jonathan (2 December 1993). "Right and wrong paths to justice". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ "'James would be 18 now – the pain of losing him will never go away'". The Observer. 2 March 2008. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ Foster, Jonathan (10 November 1993). "James Bulger suffered multiple fractures: Pathologist reveals two-year-old had 42 injuries including fractured skull. Jonathan Foster reports". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 29 August 2009.

- ^ Edwards, Richard (4 March 2010). "James Bulger case: timeline of key quotations". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 7 March 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Law Lords Department. "Judgments – Reg. v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, Ex parte V. and Reg. v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, Ex parte T". Publications.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ Johnston, Philip (3 March 2010). "Bulger killers: identifying them was a mistake". Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ a b "The Case of Jon Venables". Omand Review. 23 November 2010. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2012 – via Scribd.com.

- ^ a b Siddique, Haroon (3 March 2010). "James Bulger killing: the case history of Jon Venables and Robert Thompson". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ a b "New sentencing rules: Key cases". BBC. 7 May 2003. Archived from the original on 30 July 2004. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ "Outrage at call for Bulger killers' release". BBC. 28 October 1999. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- ^ a b Kirby, Terry (26 November 1993). "Video link to Bulger murder disputed". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Morrison, Blake (6 February 2003). "Life after James". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Two youngsters who found a new rule to break". The Guardian. 25 November 1993. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ Nowicka, Helen (19 December 1993). "Chucky films defended". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Demon ears". The Guardian. 21 March 1999. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994. Obscenity and Pornography and Videos – Section 90, Video recordings: suitability". Opsi.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ enquiries@ofsted.gov.uk, Ofsted Communications Team (5 April 2024). "Find an inspection report and registered childcare". reports.ofsted.gov.uk. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Bulger killers' trial ruled unfair". BBC News. Archived from the original on 29 April 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Penrose, Justin (7 March 2010). "Jon Venables sent back to prison over child porn offence". The Mirror. Archived from the original on 9 March 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Summary of the judgement of the ECHR". BBC News. 16 December 1999. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ "The Bulger case chronology". The Guardian. London, UK. 16 September 1999. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ Bates, Stephen (16 September 1999). "Bulger's mother puts her case". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ "Bulger killers 'released'". BBC News. 22 June 2001. Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ "Bulger statement in full". BBC News. 22 June 2001. Archived from the original on 11 March 2004. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Bulger killers 'face dangers'". BBC News. 24 June 2001. Archived from the original on 9 April 2004. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Walker, Peter (22 January 2010). "Bulger killers prove child criminals can be rehabilitated". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ Booth, Jenny (3 March 2010). "James Bulger mother: Killer Jon Venables is 'where he belongs'". The Times. London, UK: News Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ a b "Bulger killers released: What the home secretary said". BBC News. 2 March 2010. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ "Young men, full of remorse". The Guardian. 27 October 2000. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "James Bulger murder". The Guardian (composite of news articles). September 2023. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2005 – via guardian.co.uk.

- ^ "The bad seeds". Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW, AU. 11 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ Lee, Susan (11 February 2013). "Twenty years after the murder of Liverpool toddler James Bulger, his mum Denise Fergus reflects on the past and the battles still to come". The Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Pavia, Will (8 March 2010). "'It was like my son had been taken again'". The Times. London, UK. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Bulger's father visits murder scene". BBC. 4 February 2003. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008.

- ^ "Bulger 'refuge' appeal launched". BBC News. 14 March 2008. Archived from the original on 17 March 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ Franklin, Katie (14 March 2008). "James Bulger memorial appeal launched". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 March 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ "Calls to raise age of criminal responsibility rejected". BBC News. 13 March 2010. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Harris, Paul; Bright, Martin (24 June 2001) [23 June 2001]. "The secret meetings that set James's killers free". The Guardian. London, UK. The Observer. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ^ Laing, Aislinn (10 March 2010). "Bulger killer Jon Venables posed 'trivial' risk to the public, said psychiatrist". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 13 March 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ Dyer, Clare (5 December 2001). "Paper fined for Bulger order breach". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ^ "Bulger mother 'sees son's killer'". BBC News. 28 November 2004. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ "£13K to protect Bulger killers' new IDs-injunction". Sky News. 8 April 2007. Archived from the original on 10 April 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2007 – via news.sky.com.

- ^ Barrett, David (9 April 2007). "£13,000 spent protecting Bulger killers' identities". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on 12 January 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ "Man sentenced for lying over James Bulger killer". BBC News. 23 April 2010. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ McConville, Tony (6 March 2012). "Denise Fergus calls for crack down after sickening James Bulger Facebook group". Click Liverpool (clickliverpool.com). Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "'Bulger killer Jon Venables images' appear online". BBC News. 14 February 2013. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "Attorney general takes action over 'Bulger killer images'". BBC News. 25 February 2013. Archived from the original on 25 February 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "'Bulger killers' images': Two admit contempt of court". BBC News. 26 April 2013. Archived from the original on 28 April 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ "'James Bulger killer picture': James Baines sentenced". BBC News. 27 November 2013. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ "Two admit posting 'Bulger killer photos'". BBC News. 31 January 2019. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ "Tina Malone avoids jail for contempt of court over Bulger killer Facebook post". The Rhyl Journal. Press Association. 13 March 2019. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019 – via rhyljournal.co.uk.

- ^ "Jon Venables: Woman who posted picture said to show killer avoids jail". BBC News. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Margate woman jailed for 'cruel' James Bulger tweets". BBC News. 14 July 2016. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Duffy, Tom (12 October 2016). "Web troll who targeted James Bulger's mum has sentence reduced on appeal". The Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016 – via liverpoolecho.co.uk.

- ^ Bunyan, Nigel (25 October 2016). "Man jailed for stalking mother of murdered toddler James Bulger". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ Sharp, Aaron (27 March 2011). "Mother of James Bulger calls for Venables parole inquiry after reports he slept with carer". Click Liverpool. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ McConville, Tony (28 March 2011). "Cover-up denial in case of Bulger killer's sex romps". Click Liverpool. Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (23 July 2010). "Child porn charges send James Bulger's killer back to jail". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ "Jon Venables jailed for two years over child porn". The Independent. London. 23 July 2010. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ "Bulger killer Venables faces 'extremely serious' claim". BBC News. 6 March 2010. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Jamieson, Alastair (7 March 2010). "James Bulger killer Jon Venables 'accused of child porn offences'". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ^ Chung, Alison; Bonnett, Tom (8 March 2010). "Bulger killer Jon Venables jailed again 'for child porn'". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ^ Walker, Peter (7 March 2010). "Jon Venables back in prison 'over child pornography offences'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Jenkins, Russell; Ford, Richard (4 March 2010). "Jack Straw refuses to reveal why Bulger killer has returned to jail". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Ex-judge backs Venables anonymity". BBC News. 8 March 2010. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Bulger's mother says Venables 'should be identified'". BBC News. 6 March 2010. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Dodd, Vikram (2 March 2010). "James Bulger killer back in prison". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "I'm living in fear over 'child killer' rumours". The Blackpool Gazette. 10 September 2005. Archived from the original on 11 March 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ Carter, Helen (9 March 2010). "My ordeal at being mistaken for Jon Venables: Terror of young father accused of being Bulger killer". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Hough, Andrew (10 March 2010). "Jon Venables: Man wrongly accused of being James Bulger killer 'living in fear of vigilantes'". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ "'I'm not Jon Venables'". The Blackpool Gazette. 10 March 2010. Archived from the original on 11 March 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ "Bulger killer Jon Venables faces child porn charges". BBC News. 21 June 2010. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ Cheston, Paul (21 June 2010). "James Bulger killer Jon Venables is 'suspected paedophile'". The Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ Rayner, Gordon (23 July 2010). "James Bulger killer Jon Venables jailed for two years for downloading child pornography". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017.

- ^ Jack, Andy (23 July 2010). "James Bulger Killer guilty of child porn". Sky News. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ Spence, Alex (21 December 2010). "Mr. Justice Bean". The Times (profile). London, UK. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (23 July 2010). "Jon Venables jailed for two years over child pornography charges". The Guardian (online ed.). London, UK. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ Batty, David; Pidd, Helen (24 July 2010). "Inquiry ordered into parole supervision". Jon Venables case. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017 – via theguardian.com.

- ^ "Report finds no probation lapse over Venables images". BBC News. London, UK. 23 November 2010. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ "James Bulger killer Jon Venables denied parole". BBC News. 27 June 2011. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ^ Brunt, Martin (4 May 2011). "Security breach sees child killer Venables get new ID". Sky News. London, UK. Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ "James Bulger's killer Jon Venables could get second new identity after pictures leaked on internet". The Liverpool Echo. 4 May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ "City man defends decision to publish photos of Bulger killer". Express & Echo. 5 May 2011. Archived from the original on 8 May 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011 – via thisisexeter.co.uk.

- ^ "Venables 'locked up indefinitely'". Press Association. 9 November 2011. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ Osley, Richard (4 July 2013). "James Bulger killer Jon Venables to be freed". The Independent. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "James Bulger killer Jon Venables to be freed". BBC News. 4 July 2013. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "Bulger killer Jon Venables released from prison". BBC News. 3 September 2013. Archived from the original on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ Thomas, Joe (23 November 2017). "Child killer Jon Venables 'back in jail' after latest arrest". The Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "James Bulger killer Jon Venables charged over indecent images". BBC News. 5 January 2018. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ "Jon Venables jailed for owning 'paedophile manual' and a thousand indecent images of children". The Yorkshire Post. 7 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ "James Bulger killer Jon Venables denied parole over child abuse images". BBC News. 29 September 2020. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "James Bulger killer Jon Venables has parole bid rejected". Sky News. 13 December 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "James Bulger's father loses Jon Venables identity challenge". BBC News. 4 March 2019. Archived from the original on 4 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "Child killer of 2 year-old James Bulger, Jon Venables, might be sent to New Zealand". New Zealand Herald. 24 June 2019. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Wood, Richard (24 June 2019). "James Bulger murder: Infamous child killer could move to Australia". Nine News. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Cheng, Derek (24 June 2019). "Jacinda Ardern on UK child-killer Jon Venables' possible relocation to NZ - 'Don't bother applying'". New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ "'Don't bother applying' – PM's message to Jon Venables, killer of two-year-old James Bulger". 1News. 24 June 2019. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ "Festival defends 'Bulger' play". BBC News. 6 August 2001. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Gibbons, Fiachra (6 August 2001). "Family attacks use of Bulger case in 'funny' Fringe play". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Morris, Peter (8 August 2001). "In defence of my play". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Legacy Apologises For Law And Order Crime Photo". gamasutra.com. 21 June 2007. Archived from the original on 29 April 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ Billington, Michael (9 May 2009). "Monsters". The Guardian (theatre review). London, UK. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ McAlpine, Emma (15 May 2009). "Monsters at the Arcola Theatre". Spoonfed London. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Seven 'sorry' for Bulger ad". The Sydney Morning Herald. Australia: Nine Entertainment co. 30 August 2009. Archived from the original on 29 January 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ "Rumour-fuelled ratings chase". ABC (abc.net.au). 31 August 2009. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- ^ "Hollyoaks producers drop scenes echoing the killing of James Bulger". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. 15 November 2009. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Coles, Richard (30 May 2010). "On Evil by Terry Eagleton". The Guardian (book review). London, UK. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ "Detainment makes Oscars short list". Winchester Today. 21 December 2018. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "James Bulger's mother 'disgusted' over nomination". Oscars 2019. BBC News. 22 January 2019. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "Bulger mother calls on director to drop out of awards". Oscars 2019. BBC News. 24 January 2019. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ "Bulger film director 'won't withdraw' from Oscars race". BBC News. 24 January 2019. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

External links

edit- "The murder of James Bulger". Notorious murders / Young. truTV (trutv.com). Crime Library. Archived from the original on 21 January 2009.

- "How Edlington case follows course paved by Bulger trial". BBC News. 22 January 2010. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011.

- "Recollections from key people involved in the Bulger trial, ten years on". The Guardian. 6 February 2003.

- "'James would be 18 now – the pain of losing him will never go away'". The Observer. 2 March 2008.

- "Michael Jackson's 'Heal the World' released to support new Liverpool James Bulger centre for bullied children". Liverpool Daily Post. 8 October 2009. Archived from the original on 16 October 2009.

- "James Bulger's father on surviving 20 years of grief". BBC News. 12 February 2013.

- Williams, Zoe (5 July 2013). "Jon Venables: 'How attitudes towards criminality have changed and hardened'". The Guardian.

- Freeman-Powell, Shamaan (18 April 2019). "Legal dilemma of granting child killers anonymity". BBC News.