Clytemnestra (/ˌklaɪtəmˈnɛstrə/,[1] UK also /klaɪtəmˈniːstrə/;[2] Ancient Greek: Κλυταιμνήστρα, romanized: Klutaimnḗstra, pronounced [klytai̯mnɛ̌ːstraː]), in Greek mythology, was the wife of Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, and the half-sister of Helen of Sparta. In Aeschylus' Oresteia, she murders Agamemnon – said by Euripides to be her second husband – and the Trojan princess Cassandra, whom Agamemnon had taken as a war prize following the sack of Troy; however, in Homer's Odyssey, her role in Agamemnon's death is unclear and her character is significantly more subdued.

| Clytemnestra | |

|---|---|

| Greek mythology character | |

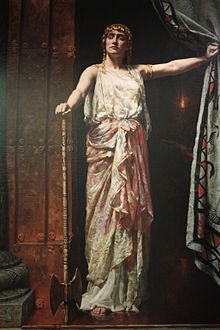

Clytemnestra, John Collier, 1882 | |

| In-universe information | |

| Family | Tyndareus (father) Leda (mother) Helen of Troy (twin half-sister) Castor and Pollux (full-brother and half-brother respectively) |

| Spouse | Tantalus, Agamemnon |

| Children | Iphigenia, Electra, Orestes, Iphianassa, Chrysothemis, Aletes, Erigone, Helen |

Name

editHer Greek name Klytaimnḗstra is also sometimes Latinized as Clytaemnestra.[3] It is commonly glossed as "famed for her suitors". However, this form is a later misreading motivated by an erroneous etymological connection to the verb mnáomai (μνάoμαι, "woo, court"). The original name form is believed to have been Klytaimḗstra (Κλυταιμήστρα) without the -n-. The present form of the name does not appear before the middle Byzantine period.[4] Homeric poetry shows an awareness of both etymologies.[5] Aeschylus, in certain wordplays on her name, appears to assume an etymological link with the verb mḗdomai (μήδoμαι, "scheme, contrive"). Thus given the derivation from κλῠτός (klutós "celebrated") and μήδομαι (mḗdomai "to plan, be cunning"), this would result in the quite descriptive "famous plotter".[6]

Background

editClytemnestra was the daughter of Tyndareus and Leda, the King and Queen of Sparta, making her a Spartan Princess. According to the myth, Zeus appeared to Leda in the form of a swan, seducing and impregnating her. Leda produced four offspring from two eggs: Castor and Clytemnestra from one egg, and Helen and Polydeuces (Pollux) from the other. Therefore, Castor and Clytemnestra were fathered by Tyndareus, whereas Helen and Polydeuces were fathered by Zeus. Her other sisters were Philonoe, Phoebe and Timandra.

Agamemnon and his brother Menelaus were in exile at the home of Tyndareus; in due time Agamemnon married Clytemnestra and Menelaus married Helen. In a late variation, Euripides's Iphigenia at Aulis, Clytemnestra's first husband was Tantalus, King of Pisa; Agamemnon killed him and Clytemnestra's infant son, then made Clytemnestra his wife. In another version, her first husband was King of Lydia.[citation needed]

Mythology

editAfter Helen was taken from Sparta to Troy, her husband, Menelaus, asked his brother Agamemnon for help. Greek forces gathered at Aulis. However, consistently weak winds prevented the fleet from sailing on the ocean. Through a subplot involving the gods and omens, the priest Calchas said the winds would be favorable if Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia to the goddess Artemis. Agamemnon persuaded Clytemnestra to send Iphigenia to him, telling her he was going to marry her to Achilles. When Iphigenia arrived at Aulis, she was sacrificed, the winds turned, and the troops set sail for Troy.

The Trojan War lasted ten years. During this period of Agamemnon's long absence, Clytemnestra began a love affair with Aegisthus, her husband's cousin. Whether Clytemnestra was seduced into the affair or entered into it independently differs according to the version of the myth.

Nevertheless, Clytemnestra and Aegisthus began plotting Agamemnon's demise. Clytemnestra was enraged by Iphigenia's murder (and presumably the earlier murder of her first husband and son by Agamemnon, and her subsequent rape and forced marriage). Aegisthus saw his father Thyestes betrayed by Agamemnon's father Atreus (Aegisthus was conceived specifically to take revenge on that branch of the family).

In old versions of the story, on returning from Troy, Agamemnon is murdered by Aegisthus, the lover of his wife, Clytemnestra. In some later versions Clytemnestra helps him or does the killing herself in his own home. The best-known version is that of Aeschylus: Agamemnon, having arrived at his palace with his concubine, the Trojan princess Cassandra, in tow and being greeted by his wife, entered the palace for a banquet while Cassandra remained in the chariot. Clytemnestra waited until he was in the bath, and then entangled him in a cloth net and stabbed him. Trapped in the web, Agamemnon could neither escape nor resist his murderer. Meanwhile, Cassandra prophesied the murder of Agamemnon and herself.

Most versions of the myth attribute her prophetic power as being a gift from Apollo in exchange for sex, while some claim that serpents from the temple of the Thymbraean Apollo flicked their tongues in her and her brother Helenus' ears, somehow giving the power of divination. In every version though, Cassandra is thereafter cursed by Apollo to be incredible, completely negating the utility of her prophecies, after refusing to have sex with the god.[7]

So, despite her ability to envisage both Agamemnon's murder and her own, her attempts to elicit help failed due to Apollo's curse making her prophesies incredible. She realized she was fated to die, and resolutely walked into the palace to receive her death.

After the murders, Aegisthus replaced Agamemnon as king and ruled for seven years with Clytemnestra as his queen. In some traditions they have three children: a son Aletes, and daughters Erigone and Helen. Clytemnestra was eventually killed by Orestes, her son by Agamemnon. The infant Helen was also killed. Aletes and Erigone grow up at Mycenae, but when Aletes comes of age, Orestes returns from Sparta, kills his half-brother, and takes the throne. Orestes and Erigone are said to have had a son, Penthilus.

Appearance in later works

editClytemnestra appears in numerous works from ancient to modern times, sometimes as a villain and sometimes as a sympathetic antihero.[8][9] Author and classicist Madeline Miller wrote "[a]fter Medea, Queen Clytemnestra is probably the most notorious woman in Greek mythology".[10]

- Clytemnestra is one of the main characters in Aeschylus's Oresteia, and is central to the plot of all three parts. She murders Agamemnon in the first play, and is murdered herself in the second. Her death then leads to the trial of Orestes by a jury composed of Athena and 12 Athenians in the final play. Her role is the largest in any surviving Greek tragedy.[11]

- In Mourning Becomes Electra, Eugene O'Neill's retelling of the Oresteia by Aeschylus, Clytemnestra is renamed Christine Mannon.

- In Ferdinando Baldi's The Forgotten Pistolero, a Spaghetti Western adaptation of the Oresteia, Clytemnestra is named Anna Carrasco and is portrayed by Luciana Paluzzi.

- The American modern dancer and choreographer Martha Graham created a two-hour ballet, Clytemnestra (1958), about the queen.

- The Aeschylus work was also adapted by South African composer Cromwell Everson into the first Afrikaans opera, Klutaimnestra, in 1967. In four acts, the opera premiered on November 7, 1967, in Biesenbach Hall, Worcester, Western Cape, South Africa.

- John Eaton composed an opera in one act entitled The Cry of Clytemnestra recounting the events leading up to and including Clytemnestra's murder of Agamemnon.

- In the 1977 film adaptation Iphigenia, Clytemnestra is portrayed by the Greek actress Irene Papas.[12]

- In the 2003 miniseries Helen of Troy, Clytemnestra is played by Katie Blake.

- Clytemnestra appears as an extremely abusive mother in the play Molora, Yaël Farber's 2007 rewriting of the Oresteia set in post-apartheid South Africa and its Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings.[13]

- The 2017 novel House of Names by Colm Tóibín is a retelling of the Oresteia, with divine elements largely removed. There are three narrators: Clytemnestra, Orestes, and Electra.

- Clytemnestra is one of several narrators of A Thousand Ships (2019) by Natalie Haynes, which retells the Trojan War from the perspective of the women involved.

- Clytemnestra is the protagonist of the eponymous novel Clytemnestra (2023) by Costanza Casati.

- An asteroid 179 Klytaemnestra is named after Clytemnestra.

References

editCitations

edit- ^ "Definition of CLYTEMNESTRA". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ , , vol. Vol. VI (ninth ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1878, p. 44.

- ^ Oresteia, Loeb edition by Alan Sommerstein, introduction, p. x, 2008.

- ^ MARQUARDT, PATRICIA A. (1992). "Clytemnestra: A Felicitous Spelling in the "Odyssey"". Arethusa. 25 (2): 241–254. ISSN 0004-0975. JSTOR 26308611.

- ^ Compare entry "Κλυταιμνήστρα", in Wiktionary.

- ^ Women of Classical Mythology: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. Copyright © 1991 by Robert E. Bell.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Daniel (July 24, 2017). "Novelizing Greek Myth". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ Haynes, Natalie (March 28, 2022). "Is Clytemnestra an Archetypically Bad Wife or a Heroically Avenging Mother?". Literary Hub. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ Miller, Madeline (November 7, 2011). "Myth of the Week: Clytemnestra". Madeline Miller. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ Monohan, Marie Adornetto. Women and Justice in Aeschylus' “Oresteia.” 1987. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, pp. 22-23.

- ^ McDonald, Marianne; Winkler, Martin M. (2001). "Michael Cacoyannis and Irene Papas on Greek Tragedy". In Martin M. Winkler (ed.). Classical Myth & Culture in the Cinema. Oxford University Press. pp. 72–89. ISBN 978-0-19-513004-1.

- ^ Farber, Yaël (2007–2011). "Molora". YAËL FARBER. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

Sources

edit- Servius. In Aeneida, xi.267.

External links

edit- Media related to Clytemnestra at Wikimedia Commons