Background

The term "gastritis" was first used in 1728 by the German Physician, Georg Ernst Stahl to describe the inflammation of the inner lining of the stomach- now known to be secondary to mucosal injury (ie, cell damage and regeneration). In the past, many considered gastritis a useful histological finding, but not a disease. This all changed with the discovery of Helicobacter pylori by Robin Warren and Barry Marshall in 1982 leading to the identification, description and classification of a multitude of different gastritides. This article focuses on the pathophysiology, etiology, epidemiology and prognosis of chronic gastritis. [1, 2]

The chronic gastritides are classified on the basis of their underlying cause (eg, H pylori, bile reflux, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], autoimmunity or allergic response) and the histopathologic pattern, which may suggest the cause and the likely clinical course (eg, H pylori–associated multifocal atrophic gastritis). Other classifications are based on the endoscopic appearance of the gastric mucosa (eg, varioliform gastritis).

It is important to distinguish between gastritis and gastropathy (in which there is cell damage and regeneration, but minimal inflammation); these entities are discussed in this article because they are frequently included in the differential diagnosis of chronic gastritis.

Chemical or reactive gastritis is caused by injury to the gastric mucosa resulting from reflux of bile and pancreatic secretions into the stomach, but it can also be caused by exogenous substances, including NSAIDs, acetylsalicylic acid, chemotherapeutic agents, and alcohol. [3] These chemicals cause epithelial damage, erosions, and ulcers that are followed by regenerative hyperplasia detectable as foveolar hyperplasia, and damage to capillaries, with mucosal edema, hemorrhage, and increased smooth muscle in the lamina propria with minimal or no inflammation.

Because there is minimal or no inflammation in these chemical-caused lesions, gastropathy or chemical gastropathy is a more appropriate description than chemical or reactive gastritis, as proposed by the updated Sydney classification of gastritis. [4] It is important to keep in mind that mixed forms of gastropathy and other types of gastritis, especially H pylori gastritis, may coexist.

There is no universally accepted classification system (including the Sydney system and Olga staging system) that provides an entirely satisfactory description of all of the gastritides and gastropathies. [5] However, an etiologic classification at least provides a direct target toward which therapy can be directed, and for this reason, such a classification is used in this article. In many instances, chronic gastritis is a relatively minor manifestation of diseases that predominantly manifest in other organs or manifest systemically (eg, gastritis in individuals who are immunosuppressed).

H pylori gastritis is a primary infection of the stomach and is the most frequent cause of chronic gastritis, infecting 50% of the global population. [6, 7, 8] Cases of histologically documented chronic gastritis are diagnosed as chronic gastritis of undetermined etiology or gastritis of undetermined type when none of the findings reflect any of the described patterns of gastritis and a specific cause cannot be identified.

For patient education resources, see the Digestive Disorders Center, as well as Gastritis.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of chronic gastritis complicating a systemic disease, such as hepatic cirrhosis, uremia, or an infection, is described in the articles specifically dealing with these diseases. The pathogenesis of the most common forms of gastritis is described below.

H pylori–associated chronic gastritis

Helicobacter pylori is the leading cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma and primary gastric lymphoma. [7, 8, 9] First described by Marshall and Warren in 1983, H pylori is a spiral gram-negative rod that has the ability to colonize and infect the stomach; the lipopolysaccharides on the outer membrane of H pylori are a major component of its ability for colonization and persistence. [9] The bacteria survive within the mucous layer that covers the gastric surface epithelium and the upper portions of the gastric foveolae. The infection is usually acquired during childhood. Once present in the stomach, the bacteria passes through the mucous layer and becomes established at the luminal surface of the stomach causing an intense inflammatory response in the underlying tissue. [2, 9, 10, 11, 12]

The presence of H pylori is associated with tissue damage and the histologic finding of both an active and a chronic gastritis. The host response to H pylori and its bacterial products is composed of T and B lymphocytes, denoting chronic gastritis, followed by infiltration of the lamina propria and gastric epithelium by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) that eventually phagocytize the bacteria. The presence of PMNs in the gastric mucosa is diagnostic of active gastritis. [13, 14]

Interaction of H pylori with the surface mucosa results in the release of interleukin (IL)-8, which leads to the recruitment of PMNs and may begin the entire inflammatory process. Gastric epithelial cells express class II molecules, which may increase the inflammatory response by presenting H pylori antigens, leading to the activation of numerous transcription factors, including NF-kB, AP-1 and CREB-1. This in turn leads to further cytokine release and more inflammation. High levels of cytokines, particularly tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [15] and multiple interleukins (eg, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17 and IL-18), are detected in the gastric mucosa of patients with H pylori gastritis. [13, 14] Increased frequencies of IL-17a+ and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) cells have been found in the antrum, particularly in individuals with H pylori-induced gastric ulcers. [16]

Leukotriene levels are also quite elevated, especially the level of leukotriene B4, which is synthesized by the host neutrophils and is cytotoxic to the gastric epithelium. [17] This inflammatory response leads to functional changes in the stomach, depending on the areas of the stomach involved. When the inflammation affects the gastric corpus, parietal cells are inhibited, leading to reduced acid secretion. Continued inflammation results in loss of the parietal cells, and the reduction in acid secretion becomes permanent.

Antral inflammation alters the interplay between gastrin and somatostatin secretion, affecting G cells (gastrin-secreting cells) and D cells (somatostatin-secreting cells), respectively. Specifically, gastrin secretion is abnormal in individuals who are infected with H pylori, with an exaggerated meal-stimulated release of gastrin being the most prominent abnormality. [18]

When the infection is cured, neutrophil infiltration of the tissue quickly resolves, with slower resolution of the chronic inflammatory cells. Paralleling the slow resolution of the monocytic infiltrates, meal-stimulated gastrin secretion returns to normal. [19]

Various strains of H pylori exhibit differences in virulence factors, and these differences influence the clinical outcome of H pylori infection. People infected with H pylori strains that secrete the vacuolating toxin A (vacA) are more likely to develop peptic ulcers than people infected with strains that do not secrete this toxin. [20]

Another set of virulence factors is encoded by the H pylori pathogenicity island (PAI). The PAI contains the sequence for several genes and encodes the CAGA gene. Strains that produce CagA protein (CagA+) are associated with a greater risk of development of gastric carcinoma and peptic ulcers. However, infection with CagA- strains also predisposes the person to these diseases. [21, 22, 23, 24]

H pylori-associated chronic gastritis progresses according to the following two main topographic patterns, which have different clinical consequences:

-

Antral predominant gastritis – This is characterized by inflammation that is mostly limited to the antrum; individuals with peptic ulcers usually demonstrate this pattern

-

Multifocal atrophic gastritis – This is characterized by the involvement of the corpus and gastric antrum with progressive development of gastric atrophy (loss of the gastric glands) and partial replacement of the gastric glands by an intestinal-type epithelium (intestinal metaplasia); individuals who develop gastric carcinoma and gastric ulcers usually demonstrate this pattern.

As previously mentioned, 50% of the world's population is infected with H pylori. The overwhelming majority of those infected do not develop significant clinical complications and remain carriers with asymptomatic chronic gastritis. Some individuals who carry additional risk factors may develop peptic ulcers, gastric mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, or gastric adenocarcinomas.

An increased duodenal acid load may precipitate and wash out the bile salts, which normally inhibit the growth of H pylori. Progressive damage to the duodenum promotes gastric foveolar metaplasia, resulting in sites for H pylori growth and more inflammation. This cycle renders the duodenal bulb increasingly unable to neutralize acid entering from the stomach until changes in the bulb structure and function are sufficient for an ulcer to develop. H pylori can survive in areas of gastric metaplasia in the duodenum, contributing to the development of peptic ulcers. [11]

MALT lymphomas may develop in association with chronic gastritis secondary to H pylori infection. The stomach usually lacks organized lymphoid tissue, but after infection with H pylori, lymphoid tissue is universally present. Acquisition of gastric lymphoid tissue is thought to be due to persistent antigen stimulation from byproducts of chronic infection with H pylori. [25]

The continuous presence of H pylori results in the persistence of MALT in the gastric mucosa, which eventually may progress to form low- and high-grade MALT lymphomas. MALT lymphomas are monoclonal proliferations of neoplastic B cells that have the ability to infiltrate gastric glands. Gastric MALT lymphomas typically are low-grade T-cell–dependent B-cell lymphomas, and the antigenic stimulus of gastric MALT lymphomas is thought to be H pylori.

Another complication of H pylori gastritis is the development of gastric carcinomas, especially in individuals who develop extensive atrophy and intestinal metaplasia of the gastric mucosa. It is well accepted that a multistep process initiated by H pylori related chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa progresses to chronic atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and finally leading to the development adenocarcinoma. Although the relationship between H pylori and gastritis is constant, only a small proportion of individuals infected with H pylori develop gastric cancer; the exact mechanism for this relationship with gastric carcinogenesis remains unclear, but host genetic background may play a role. [8] The incidence of gastric cancer usually parallels the incidence of H pylori infection in countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer and is consistent with H pylori being the cause of the precursor lesion, chronic atrophic gastritis. [25, 26]

H pylori-related chronic gastritis may also increase the risk of endothelial dysfunction, and thus vascular disease, due to abnormalities in flow-mediated dilation and carotid intima media thickness, as well as elevated levels of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). [27]

Persistence of the organisms and associated inflammation during long-standing infection is likely to permit the accumulation of mutations in the genome of the gastric epithelial cells, leading to an increased risk of malignant transformation and progression to adenocarcinoma. Studies have provided evidence of the accumulation of the mutations in the gastric epithelium secondary to oxidative DNA damage associated with chronic inflammatory byproducts and secondary to deficiency of DNA repair induced by chronic bacterial infection.

Although the role of H pylori in peptic ulcer disease is well established, the role of the infection in non-ulcer or functional dyspepsia remains highly controversial. A recent meta-analysis demonstrates that H pylori eradication therapy is associated with an improvement of dyspeptic symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia in Asian, European, and American populations. [28] Although this study illustrates that H pylori eradication may be beneficial for symptom relief in some populations, routine H pylori testing and treatment in nonulcer dyspepsia are not currently widely accepted. Therefore, H pylori eradication strategies in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia must be considered on a patient-by-patient basis.

Infectious granulomatous gastritis

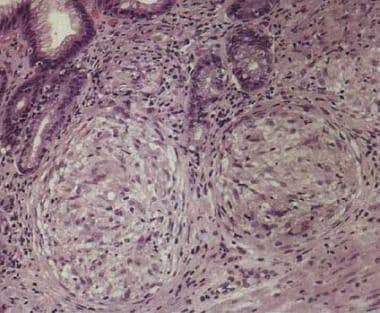

Granulomatous gastritis (see the image below) is a rare entity. Tuberculosis may affect the stomach and cause caseating granulomas. Fungi, including cryptococcus, can also cause caseating granulomas and necrosis, a finding that is usually observed in patients who are immunosuppressed. Granulomatous gastritis has also been associated with H pylori infection. [29]

Granulomatous chronic gastritis. Noncaseating granulomas in the lamina propria. Image courtesy of Sydney Finkelstein, MD, PhD, University of Pittsburgh.

Granulomatous chronic gastritis. Noncaseating granulomas in the lamina propria. Image courtesy of Sydney Finkelstein, MD, PhD, University of Pittsburgh.

Gastritis in patients who are immunosuppressed

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection of the stomach is observed in patients with underlying immunosuppression, but it remains unclear whether CMV gastritis promotes the development of gastric carcinoma. [30] Histologically, a patchy, mild inflammatory infiltrate is observed in the lamina propria. Typical intranuclear eosinophilic inclusions and, occasionally, smaller intracytoplasmic inclusions are present in the gastric epithelial cells and in the endothelial or mesenchymal cells in the lamina propria. Severe necrosis may result in ulceration.

Other infectious causes of chronic gastritis in immunosuppressed patients, include the Herpes simplex virus (HSV), which causes basophilic intranuclear inclusions in epithelial cells. Mycobacterial infections involving Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare are characterized by diffuse infiltration of the lamina propria by histiocytes, which rarely form granulomas.

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis is associated with serum anti-parietal and anti–intrinsic factor (IF) antibodies. The gastric corpus undergoes progressive atrophy, IF deficiency occurs, and patients may develop pernicious anemia. [31]

The development of chronic atrophic gastritis (sometimes called type A gastritis) limited to corpus-fundus mucosa and marked diffuse atrophy of parietal and chief cells characterizes autoimmune atrophic gastritis. In addition to hypochlorhydria, autoimmune gastritis is associated with serum anti-parietal and anti-IF antibodies that cause IF deficiency, which, in turn, causes decreased availability of cobalamin, eventually leading to pernicious anemia in some patients. Hypochlorhydria induces G-Cell (Gastrin producing) hyperplasia, leading to hypergastrinemia. Gastrin exerts a trophic effect on enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells and is hypothesized to be one of the mechanisms leading to the development of gastric carcinoid tumors (ECL tumors). [32, 33]

In autoimmune gastritis, autoantibodies are directed against at least 3 antigens, including IF, cytoplasmic (microsomal-canalicular), and plasma membrane antigens. There are two types of IF antibodies, types I and II. Type 1 antibody prevents the attachment of B12 to IF and Type II antibody prevents attachment of the vitamin B12-intrinsic factor complex to ileal receptors. [34]

Cell-mediated immunity also contributes to the disease. T-cell lymphocytes infiltrate the gastric mucosa and contribute to the epithelial cell destruction and resulting gastric atrophy.

Chronic reactive chemical gastropathy

Chronic reactive chemical gastritis is associated with long-term intake of aspirin or NSAIDs. It also develops when bile-containing intestinal contents reflux into the stomach. Although bile reflux may occur in the intact stomach, most of the features associated with bile reflux are typically found in patients with partial gastrectomy, in whom the lesions develop near the surgical stoma.

The mechanisms through which bile alters the gastric epithelium involve the effects of several bile constituents. Both lysolecithin and bile acids can disrupt the gastric mucous barrier, allowing the back diffusion of positive hydrogen ions and resulting in cellular injury. Pancreatic juice enhances epithelial injury in addition to bile acids. In contrast to other chronic gastropathies, minimal inflammation of the gastric mucosa typically occurs in chemical gastropathy.

Chronic noninfectious granulomatous gastritis

Noninfectious diseases are the usual cause of gastric granulomas; these include Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, and isolated granulomatous gastritis. Crohn disease demonstrates gastric involvement in approximately 33% of the cases. Granulomas have also been described in association with gastric malignancies, including carcinoma and malignant lymphoma. Sarcoidlike granulomas may be observed in people who use cocaine, and foreign material is occasionally observed in the granuloma. An underlying cause of chronic granulomatous gastritis cannot be identified in up to 25% of cases. These patients are considered to have idiopathic granulomatous gastritis (IGG). [35]

Lymphocytic gastritis

Lymphocytic gastritis is a type of chronic gastritis characterized by dense infiltration of the surface and foveolar epithelium by T lymphocytes and associated chronic infiltrates in the lamina propria. Because its histopathology is similar to that of celiac disease, lymphocytic gastritis has been proposed to result from intraluminal antigens. [36, 37, 38, 39, 40]

High anti–H pylori antibody titers have been found in patients with lymphocytic gastritis, and in limited studies, the inflammation disappeared after H pylori was eradicated. [41] However, many patients with lymphocytic gastritis are serologically negative for H pylori. A number of cases may develop secondary to intolerance to gluten and drugs such as ticlopidine. [38, 42]

Eosinophilic gastritis

Large numbers of eosinophils may be observed with parasitic infections such as those caused by Eustoma rotundatum and Anisakis marina. Eosinophilic gastritis can be part of the spectrum of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Although the gastric antrum is commonly affected and can cause gastric outlet obstruction, this condition can affect any segment of the GI tract and can be segmental. [43] Patients frequently have peripheral blood eosinophilia.

In some cases, especially in children, eosinophilic gastroenteritis can result from food allergy, usually to milk or soy protein. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis can also be found in some patients with connective tissue disorders, including scleroderma, polymyositis, and dermatomyositis.

Radiation gastritis

Radiation gastritis usually occurs 2-9 mo after the initial radiotherapy. The dose at which 5% of patients develop complications at 5 years, when the entire stomach is irradiated, is estimated to be 50 Gy. Small doses of radiation (up to 15 Gy) cause reversible mucosal damage, whereas higher doses cause irreversible damage with atrophy and ischemic-related ulceration. Reversible changes consist of degenerative changes in the epithelial cells and nonspecific chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria. Higher amounts of radiation cause permanent mucosal damage, with atrophy of the fundic glands, mucosal erosions, and capillary hemorrhage. Associated submucosal endarteritis results in mucosal ischemia and secondary ulcer development. [44, 45]

Ischemic gastritis

Ischemic gastritis is believed to result from atherosclerotic thrombi arising from the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries. [46, 47]

Etiology

Chronic gastritis may be caused by either infectious or noninfectious conditions. Infectious forms of gastritis include the following:

-

Chronic gastritis caused by H pylori infection – This is the most common cause of chronic gastritis. [48]

-

Gastritis caused by Helicobacter heilmannii infection [49]

-

Granulomatous gastritis associated with gastric infections in mycobacteriosis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, mucormycosis, South American blastomycosis, anisakiasis, or anisakidosis

-

Chronic gastritis associated with parasitic infections -Strongyloides species, schistosomiasis, or Diphyllobothrium latum

-

Gastritis caused by viral (eg, CMV or herpesvirus) infection [50]

Noninfectious forms of gastritis include the following:

-

Autoimmune gastritis

-

Chemical gastropathy- usually related to chronic bile reflux, NSAID and aspirin intake [51]

-

Uremic gastropathy

-

Chronic noninfectious granulomatous gastritis [35, 52, 53] – This may be associated with Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis, foreign bodies, cocaine use, isolated granulomatous gastritis, chronic granulomatous disease of childhood, eosinophilic granuloma, allergic granulomatosis and vasculitis, plasma cell granulomas, rheumatoid nodules, tumoral amyloidosis and granulomas associated with gastric carcinoma, gastric lymphoma, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis

-

Lymphocytic gastritis, including gastritis associated with celiac disease (also called collagenous gastritis) [36, 37, 38, 39, 54, 55] About 16% of patients with celiac disease have lymphocytic gastritis, which improves after a gluten-free diet, but there does not appear to be an association between lymphocytic gastritis and H pylori infection. [55] Chronic gastritis, whether active or inactive, does not appear to be affected by a gluten-free diet. [55]

-

Eosinophilic gastritis

-

Radiation injury to the stomach

-

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

-

Ischemic gastritis [46]

-

Gastritis secondary to drug therapy (NSAIDs and aspirin)

Some patients have chronic gastritis of undetermined etiology or gastritis of undetermined type (eg, autistic gastritis [56] ).

Epidemiology

United States statistics

H pylori is one of the most prevalent bacterial pathogens in humans, and in the United States approximately 30%-35% of adults are infected, but the prevalence of infection in minority groups and immigrants from developing countries is much higher. H pylori prevalence is higher in Hispanics (52%) and black individuals (54%), in contrast to white persons (21%). Overall, the prevalence of H pylori is higher in developing countries and declining in the United States. The incidence of new infections in developing countries ranges from 3%-10% of the population each year, compared to 0.5% in developed countries. Children aged 2-8 years in developing nations acquire the infection at a rate of about 10% per year, whereas in the United States, children become infected at a rate of less than 1% per year. This major difference in the rate of acquisition in childhood is responsible for the differences in the epidemiology between developed countries and developing countries. [19, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62]

Socioeconomic differences are the most important predictor of the prevalence of the infection in any group. Higher standards of living are associated with higher levels of education and better sanitation, thus the prevalence of infection is lower. Epidemiologic studies of H pylori-associated chronic gastritis have shown that the acquisition of the infection is associated with large, crowded households and lower socioeconomic status. [63, 64]

Well-defined preventive measures are not established. However, in the United States and in other countries with modern sanitation and clean water supplies, the rate of acquisition has been decreasing since 1950. In fact, the risk of H pylori infection in immigrants to the United States appears to be decreasing with each successive generation born in the United States. The rate of infection in people with several generations of their families living at a high socioeconomic status is in the range of 10%-15%. This is probably the lowest level to which prevalence can decline spontaneously until eradication or vaccination programs are instituted. [63, 65, 66]

Lymphocytic gastritis has an incidence of between 0.83% and 2.5% in patients undergoing endoscopy and of 4%-5% in those with chronic gastritis. The disease has been reported in various parts of the world but more commonly in Europe, and it appears to be less common in the United States. [67, 68]

Chronic reactive chemical gastropathy is one of the most common and poorly recognized lesions of the stomach.

International statistics

An estimated 50% of the world population is infected with H pylori; consequently, chronic gastritis is extremely frequent. H pylori infection is highly prevalent in Asia and in developing countries, and multifocal atrophic gastritis and gastric adenocarcinomas are more prevalent in these areas. [6, 61, 62, 69]

Autoimmune gastritis is a relatively rare disease, most frequently observed in individuals of northern European descent [3, 70] and black people. The prevalence of pernicious anemia, resulting from autoimmune gastritis, has been estimated at 127 cases per 100,000 population in the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Sweden. The frequency of pernicious anemia is increased in patients with other immunologic diseases, including Graves disease, myxedema, thyroiditis, vitiligo and hypoparathyroidism. [71, 72, 73]

Age-related demographics

Age is the most important variable relating to the prevalence of H pylori infection, with persons born before 1950 having a notably higher rate of infection than those born after 1950. For example, roughly 50% of people older than 60 years are infected, compared with 20% of people younger than 40 years. [66, 74, 75]

However, this increase in infection prevalence with age is largely apparent rather than real, reflecting a continuing overall decline in the prevalence of H pylori infection. Because the infection is typically acquired in childhood and is life long, the high proportion of older individuals who are infected is the long-term result of infection that occurred in childhood when standards of living were lower. The prevalence will decrease as people who are currently aged 40 years and have a lower rate of infection grow older (a birth cohort phenomenon).

H pylori gastritis is usually acquired during childhood, and complications typically develop later. [76, 77, 78]

Patients with autoimmune gastritis usually present with pernicious anemia, which is typically diagnosed in individuals aged approximately 60 years. However, pernicious anemia can also be detected in children (juvenile pernicious anemia). [79, 80]

Lymphocytic gastritis can be observed in children but is usually detected in late adulthood. On average, patients are aged 50 years. [75]

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis mostly affects people younger than 50 years. [81]

Sex-related demographics

Chronic H pylori-associated gastritis affects both sexes with approximately the same frequency, though some studies have noted a slight male predominance. [82] The female-to-male ratio for autoimmune gastritis has been reported to be 3:1. Lymphocytic gastritis affects men and women at similar rates. [75]

Race-related demographics

H pylori-associated chronic gastritis appears to be more common among Asian and Hispanic people than in people of other races. In the United States, H pylori infection is more common among black, Native American, and Hispanic people than among white people, a difference that has been attributed to socioeconomic factors. [59, 60, 65]

Autoimmune gastritis is more frequent in individuals of northern European descent and in black people, and it is less frequent in southern European and Asian people. [31]

Prognosis

The prognosis of chronic gastritis is strongly related to the underlying cause. Chronic gastritis as a primary disease, such as H pylori-associated chronic gastritis, may progress as an asymptomatic disease in some patients, whereas other patients may report dyspeptic symptoms. The clinical course may be worsened when patients develop any of the possible complications of H pylori infection, such as peptic ulcer or gastric malignancy. [25]

H pylori gastritis is the most frequent cause of MALT lymphoma- occurring in 0.1% of those infected. Patients with chronic atrophic gastritis may have a 12- to 16-fold increased risk of developing gastric carcinoma, compared with the general population. Approximately 10% of infected persons develop peptic ulcer and the lifetime risk of gastric cancer is in the range of 1%-3%. [83]

Eradication of H pylori results in rapid cure of the infection with disappearance of the neutrophilic infiltration of the gastric mucosa. Disappearance of the lymphoid component of gastritis might take several months after treatment. Data on the evolution of atrophic gastritis after eradication of H pylori have been conflicting. Follow-up for as long as several years after H pylori eradication has not demonstrated regression of gastric atrophy in most studies, whereas others report improvement in the extent of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. [84, 85]

Another important question is whether H pylori eradication in a patient with atrophic gastritis reduces the risk of gastric cancer development. Unfortunately, the data up to now has been mixed. A prospective study in a Japanese population reported that H pylori eradication in patients with endoscopically resected early gastric cancer resulted in the decreased appearance of new early cancers, whereas intestinal-type gastric cancers developed in the control group without H pylori eradication. This finding supports an intervention approach with eradication of H pylori if the organisms are detected in patients with atrophic gastritis; the goal is to prevent the development of gastric cancer. [86, 87, 88] However, recent reports have shown that gastric cancers can still arise after adequate H pylori therapy. [89, 90]

In patients with autoimmune gastritis, the major effects are consequent to the loss of parietal and chief cells and include achlorhydria, hypergastrinemia, loss of pepsin and pepsinogen, anemia, and an increased risk of gastric neoplasms. The prevalence of gastric neoplasia in patients with pernicious anemia, is reported to be about 1%-3% for adenocarcinoma and 1%-7% for gastric carcinoid. [91, 92]

-

Helicobacter pylori–caused chronic active gastritis. Genta stain (×20). Multiple organisms (brown) are visibly adherent to gastric surface epithelial cells.

-

Chronic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. Numerous plasma cells are present in the lamina propria.

-

Granulomatous chronic gastritis. Noncaseating granulomas in the lamina propria. Image courtesy of Sydney Finkelstein, MD, PhD, University of Pittsburgh.

-

Chronic gastritis. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare in the gastric lamina propria macrophages. Image courtesy of Sydney Finkelstein, MD, PhD, University of Pittsburgh.

-

Chronic gastritis. Typical cytomegalovirus inclusions in the lamina propria capillary endothelial cells. Image courtesy of Sydney Finkelstein, MD, PhD, University of Pittsburgh.

-

Chronic gastritis. Chemical gastropathy. Image courtesy of Sydney Finkelstein, MD, PhD, University of Pittsburgh.

-

Lymphocytic chronic gastritis. Gastric epithelium is studded with numerous lymphocytes (left). Intraepithelial lymphocytes are T-cell lymphocytes shown by immunoreactivity to CD3 (brown stain, right).