The Qing dynasty was the last of China’s royal dynasties. The Qing ruled from 1644 until the abdication of their last emperor, the infant Puyi, in February 1912. The Qing period was one of rapid and profound change in China. Qing emperors were confronted by numerous challenges, including the arrival of foreigners and Christian missionaries, internal unrest and rebellions and the weakening of their centralised power. By the 19th century, China was being threatened and bullied by Western imperial powers, particularly Britain. Unable to defend the nation from foreign imperialists, the Qing was condemned for being too weak, too corrupt and too unwilling to embrace change and modernisation. The origins of the Chinese Revolution can be found in this declining respect for the Qing regime.

The founders of the Qing dynasty came originally from Manchuria, a northern region sandwiched between China, Mongolia and Siberia (Russia). Unlike the majority of Chinese, who were of the Han ethnic group, the Manchurians were from a different tribal-ethnic group called the Jurchens. In the early 1600s, Jurchen leaders established a military stronghold in Manchuria and defied the weakening authority of China’s Ming emperors. This led to challenges, confrontation, territorial disputes and threats of war between Ming rulers in Beijing and the northern Jurchens, who were by now known as Manchus. In April and May 1644, a Manchu army crossed the Great Wall, marched south and entered Beijing. Their progress was aided by Ming collaborators and peasants who were dissatisfied with the Ming’s financial incompetence. With a Manchu takeover of Beijing imminent, the last Ming ruler, the Chongzhen Emperor, hanged himself in a tree near the Forbidden City. In November 1644 a Manchu prince was crowned as the Shunzhi Emperor: the first Qing ruler of China.

The new emperor’s royal court, advisory council and military command were populated almost entirely with Manchus. The Qing emperors also introduced elements of Manchu language and culture to China. One of the more visible was the adoption of the Manchu queue: a male hairstyle featuring a high shaved forehead and a long braided ponytail. The distinctive queue was imposed on the majority Han Chinese as a sign of submission to their new rulers. Wearing the queue was an act of obedience and conformity to the Qing; not wearing it was an act of defiance. In 1645 the Manchu warlord Dorgon gave all Chinese men ten days to adopt the queue or face the death penalty. Dorgon’s order was resisted in parts of China, in some places for several years. Manchu officials and military officers occasionally carried out mass executions against those who failed to comply. The queue remained a symbol of Qing oppression until the 1911 revolution. Western cartoonists sometimes used the queue as a symbol of a backward regime that had outstayed its welcome.

The Manchu did not impose all of their cultural traits on the Han Chinese. Some of their cultural motifs were retained exclusively for royalty, officials and soldiers, as a means of distinguishing the ruling classes from commoners. Early in their reign, the Manchu created the Eight Banners system. This system was a military organisation, first and foremost, the emperor’s means of asserting control and defending his empire. It also dictated political and social structure, placing Manchu families under banners of different colours and status, while distinguishing them from non-Manchu Chinese. Manchu ‘Bannermen’ enjoyed recognition and political and economic privileges, including access to money, food and housing if it was needed. The Eight Banners was an important system in the first century of Qing rule, however, its military effectiveness weakened over time. The Banners system continued to reinforce Manchu values and elitism through the 17th and 18th century, though it was diluted by the admission of non-Manchu Chinese.

“There are still some races – such as the Miao, Tong and Yao – who live interspersed among people of a superior race and do not mix. Their extinction, however, cannot be long delayed. Why? Because if they do not amalgamate, they must struggle; and when they struggle, one side must lose. Victory or defeat depends entirely upon who is superior or inferior. Today, as between the Manchus and the Han, it takes no expert to establish which is the superior race and which is the inferior.”

Liang Qichao, historian

The 1700s was the high point of Qing rule. Their empire was stable, China’s borders were secure, agricultural production was strong enough to keep food shortages at bay and peasant taxes low. Some of the early Qing emperors were reformers who introduced new methods of control but complemented them with progressive economic and social reforms. Internal trade flourished under the Qing and the middle and manufacturing classes – artisans, storekeepers, goods hauliers and money lenders – flourished and grew in number. Qing officials also opened up new tracts of land for farming; by the late 1700s, almost all of China’s arable land was being utilised. New methods of rice farming were developed, while new crops such as corn were imported, grown and harvested. These reforms boosted production and living standards, which during the first two centuries of Qing rule exceeded conditions in other parts of the world, including Europe. There were also advances in culture and the arts, though for the first time in centuries China began to lag behind the West in technological innovation and scientific discovery.

In general terms, the 1800s were much less successful for both the Qing and their subjects. During this century the Qing government was challenged by several threats and problems: economic pressures, corruption in the government and bureaucracy, domestic rebellions, foreign imperialism and wars. The high living standards of the previous century contributed to a sharp increase in population. China’s population exceeded 300 million in 1750 but just a century later it was as high as 400 million. This spike produced an increase in population density, which became severe in some eastern provinces. It also created an excess of labour, land shortages, inadequate food production and several famines. The Chinese working classes were also affected by high levels of taxation and an alarming degree of corruption by Qing officials. The growing unhappiness with Qing rule fuelled peasant unrest through the 19th century. The 1851 Taiping Rebellion in Guangxi province, south-eastern China, was motivated both by dissatisfaction with the Qing and the Christian beliefs of rebel leaders. This rebellion was eventually suppressed by the imperial government, though it took more than 12 years and cost millions of lives.

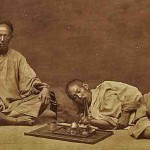

The most potent threat to Qing authority, however, came from beyond. China’s economic prosperity, manufacturing growth and trade potential gave rise to foreign interest in the Middle Kingdom. In the late 1700s, European maritime powers like Great Britain began seeking commercial agreements, trading rights and access to ports in China. Among the surge of foreign arrivals in China were hundreds of Christian missionaries, intent on proselytising [promoting their religion] and converting non-Christian Chinese. Eager to engineer a favourable balance of trade, the British were aggressive in encouraging and expanding the sale of opium, a narcotic drug made from poppies, within China. Recognising the dangers of opium addiction, Qing leaders banned the importation of opium, a decision that led to two Opium Wars with the British (1839-42 and 1856-60). Both conflicts were disastrous for China. Not only were the Opium Wars finalised with costly and humiliating treaties, they also exposed the backwardness and inadequacy of the Qing military. By the end of the second Opium War, the Qing dynasty had been exposed as militarily weak and politically impotent. With respect for the Qing in rapid decline, the gates were opened for reformists and revolutionaries to demand change.

1. The Qing dynasty was the last of China’s imperial dynasties. It was initiated in 1644 by the Manchu, an ethnic group from the north who invaded Beijing and ousted the incumbent Ming Dynasty.

2. The Manchu imposed some of their cultural traditions, such as the queue hairstyle, on Chinese society. For the most part, however, they remained elitist and isolated from the majority Han Chinese.

3. The 1700s were the high point of Qing rule, marked by political stability, economic prosperity, improving living conditions and population growth.

4. By the late 1800s, however, the Qing had been challenged and undermined by a number of factors including the high population, food shortages, excessive taxation, government corruption, domestic rebellions and the incursion of foreign imperialists.

5. British incursions into China led to the production and sale of opium, a narcotic drug. When the British defeated China in the two Opium Wars, it exposed the political and military weakness of the Qing regime.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Glen Kucha and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

G. Kucha & J. Llewellyn, “The Manchu and the Qing dynasty“, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/manchu-qing-dynasty/.

This website uses pinyin romanisations of Chinese words and names. Please refer to this page for more information.