You won't achieve understanding of a person or an issue in a day. Take your time, dig, go back.

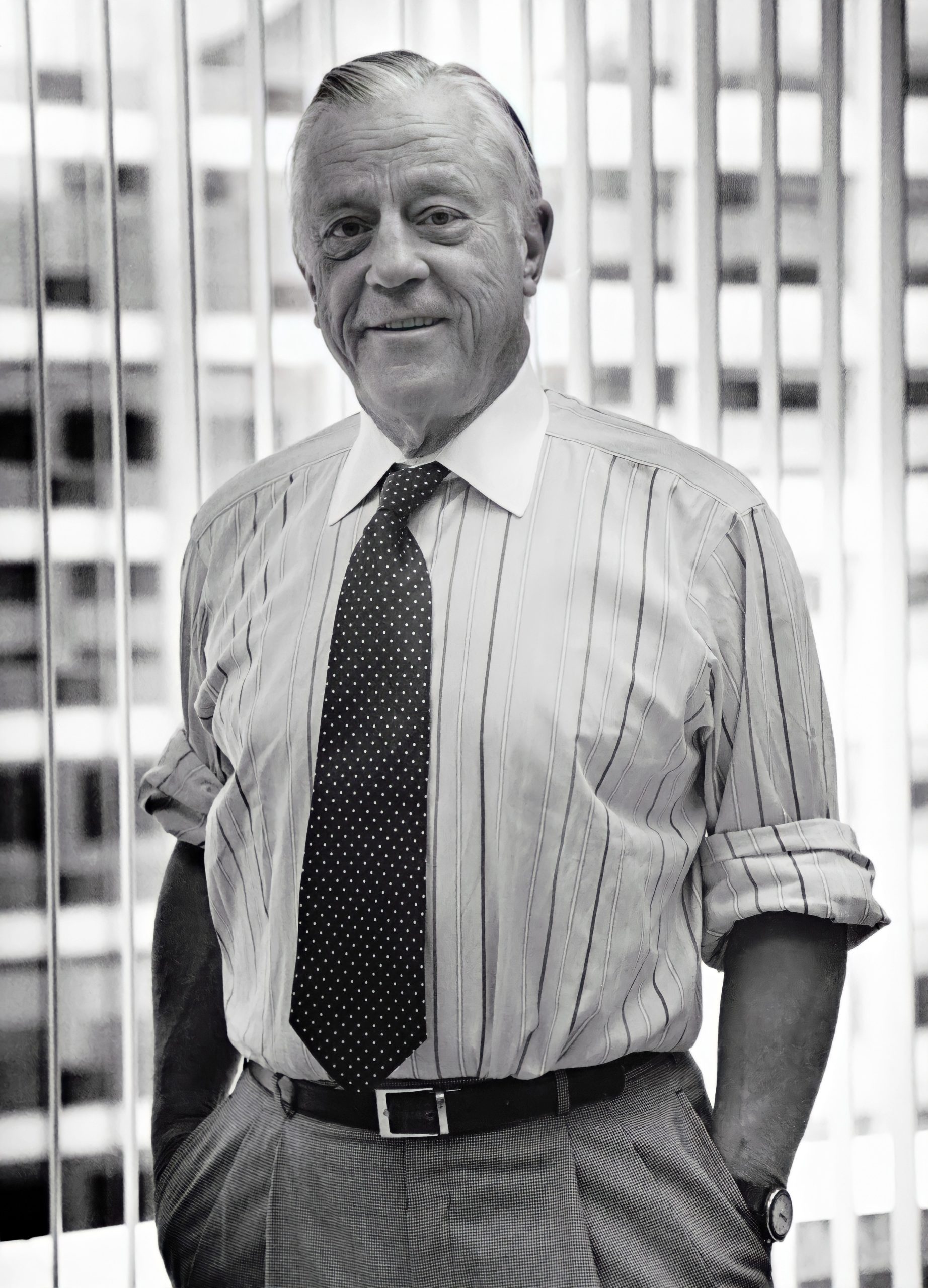

Robert U. Woodward was born in Geneva, Illinois, and raised in nearby Wheaton. Woodward’s father was a prominent attorney, and hoped that Robert would follow in his footsteps. He attended Yale University on a Naval ROTC scholarship, and majored in history and English literature.

A few weeks after receiving his bachelor’s degree in 1965, he entered the United States Navy for a four-year tour of duty. The American escalation in Vietnam had just begun. When Woodward left the Navy, American involvement in Vietnam — and domestic opposition to the war — were at their height.

At the end of his military service, Woodward applied to Harvard Law School, and was accepted for the fall 1970 term, but he chose to pursue a career in journalism instead. He persuaded The Washington Post to give him an unpaid two-week try-out. Not one of the 17 stories he filed was printed. The Post editors concluded that he was not ready for a major metropolitan daily newspaper, and arranged for him to take job as one of four reporters at a small suburban weekly, The Montgomery County Sentinel.

He quickly tired of the routine assignments his position offered, and began to hunt for news on his own. He soon became the paper’s leading reporter, and by September 1971, the Post was ready to give him another try. He was assigned to the police beat, from 7:00 in the evening to 3:00 in the morning, but he did not limit his work activities to his assigned hours.

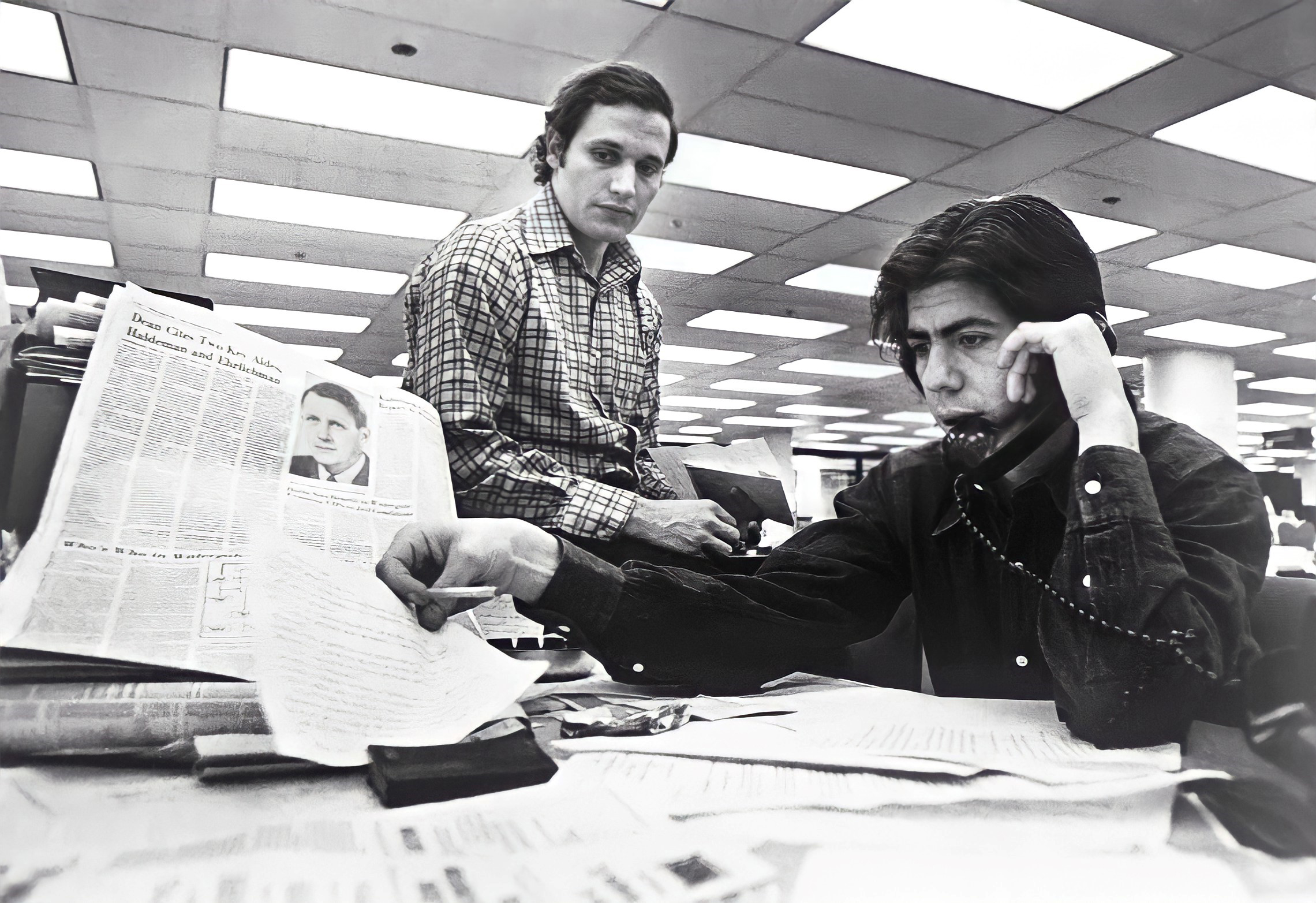

By day, he circulated in the city’s government offices, and pressed civil servants for every piece of information that might prove useful. Within a year, his byline was appearing on the front page. Early one Saturday morning, June 17, 1972, the Post’s city editor called Woodward to tell him that five men with cameras and electronic surveillance equipment had been arrested breaking into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate office complex. Woodward was assigned to cover the breaking story, along with a younger but more experienced reporter, Carl Bernstein. Although Woodward and Bernstein were able to link the burglary of Democratic National Headquarters to operatives inside the Nixon White House, and to President Nixon’s re-election campaign, they were unable at first to prove any direct involvement by the president or his senior staff to either the burglary or its subsequent cover-up. Most news outlets dropped the story, and Nixon was re-elected in a historic landslide.

When the Post persevered with the investigation, President Nixon induced the FCC to challenge the licenses of the Post’s television stations. With the full support of their editor, Ben Bradlee, Woodward and Bernstein continued to pursue the story, and little by little uncovered a larger story of the abuse of power and the obstruction of justice. Woodward gained valuable information through an unnamed informant, nicknamed “Deep Throat,” by Post managing editor Howard Simon. Woodward’s critics insisted that this informant was a fabrication, or at best, a composite based on a number of sources. Woodward would only reveal his informant was an individual working in the Executive Branch. For over 30 years, the informant’s identity was known only to the man himself, and to Woodward, Bernstein and Bradlee.

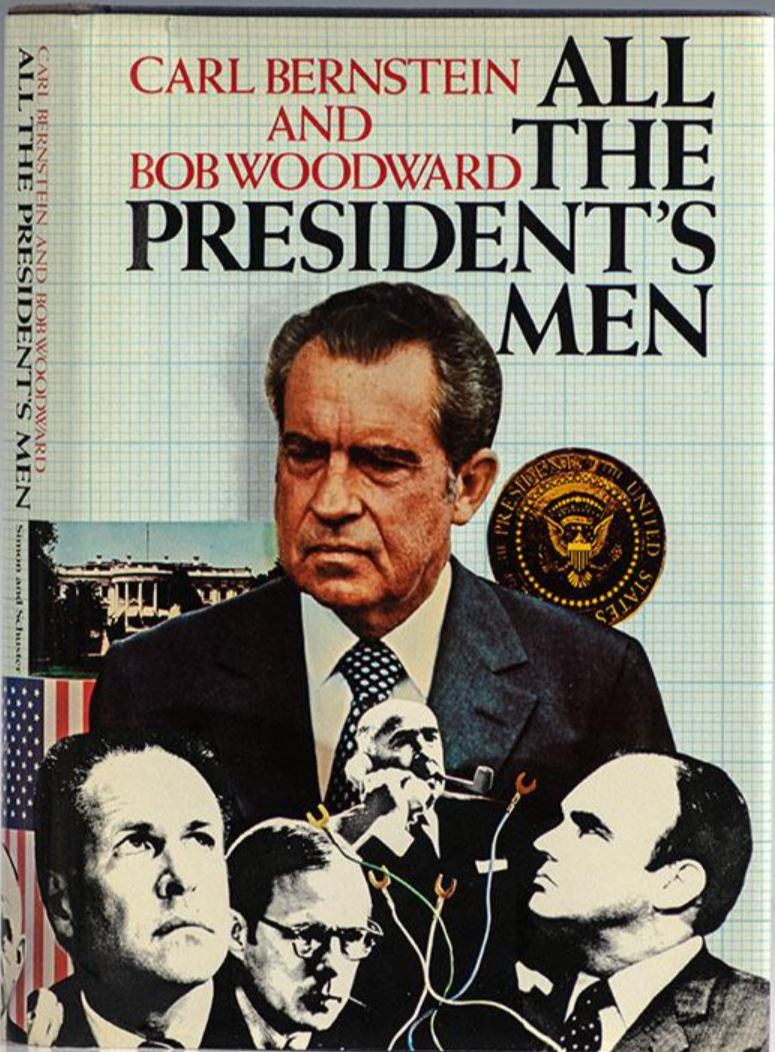

In August 1974, President Nixon, facing near certain impeachment and conviction, resigned his office and accepted a blanket pardon for any actions he may have committed in office. Woodward and Bernstein’s account of the investigation, All The President’s Men, became a national bestseller and was made into a popular motion picture. TIME magazine has called All the President’s Men “perhaps the most influential piece of journalism in history.” A second book by Woodward and Bernstein on the collapse of the Nixon administration, The Final Days, was also a huge success.

With astonishing regularity, Woodward has continued to produce bestselling books on previously hidden aspects of American life. His works to date include The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court; The Man Who Would Be President: Dan Quayle; Wired: The Short Life and Fast Times of John Belushi; Veil: The Secret Ways of the CIA; The Commanders, a look inside the decision-making process behind the 1991 Persian Gulf War; The Agenda: Inside the Clinton White House; The Choice, on the 1996 presidential campaign, and Maestro, on longtime Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan. Since 2003, he has written four books on President George W. Bush’s conduct of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq: Bush at War, Plan of Attack, State of Denial and The War Within. He continued the story of presidential leadership and foreign policy in Obama’s Wars (2010).

In 2005, the mystery surrounding the identity of Watergate informant “Deep Throat” was ended. W. Mark Felt, Sr., a retired associate director of the FBI, revealed that he had provided Woodward with details of the Watergate cover-up. Woodward, Carl Bernstein and Ben Bradlee all confirmed Felt’s revelation. A career FBI agent, Felt held the second ranking post in the FBI at the time of the Watergate break-in and made his disclosures to Woodward when Nixon’s appointed FBI director failed to act on information incriminating members of the administration. Woodward immediately published a full account of his dealings with Felt in his book, The Secret Man.

Woodward’s 2012 book The Price of Politics explores the efforts of President Obama and congressional leaders to restore the American economy following the financial crisis of 2008. On the eve of the 2016 election, Woodward returned to the Watergate story one more time. In The Last of the President’s Men, Woodward told the story of Alexander Butterfield, the White House aide who disclosed the existence of President Nixon’s secret recording system, the revelation that ultimately led to Nixon’s downfall.

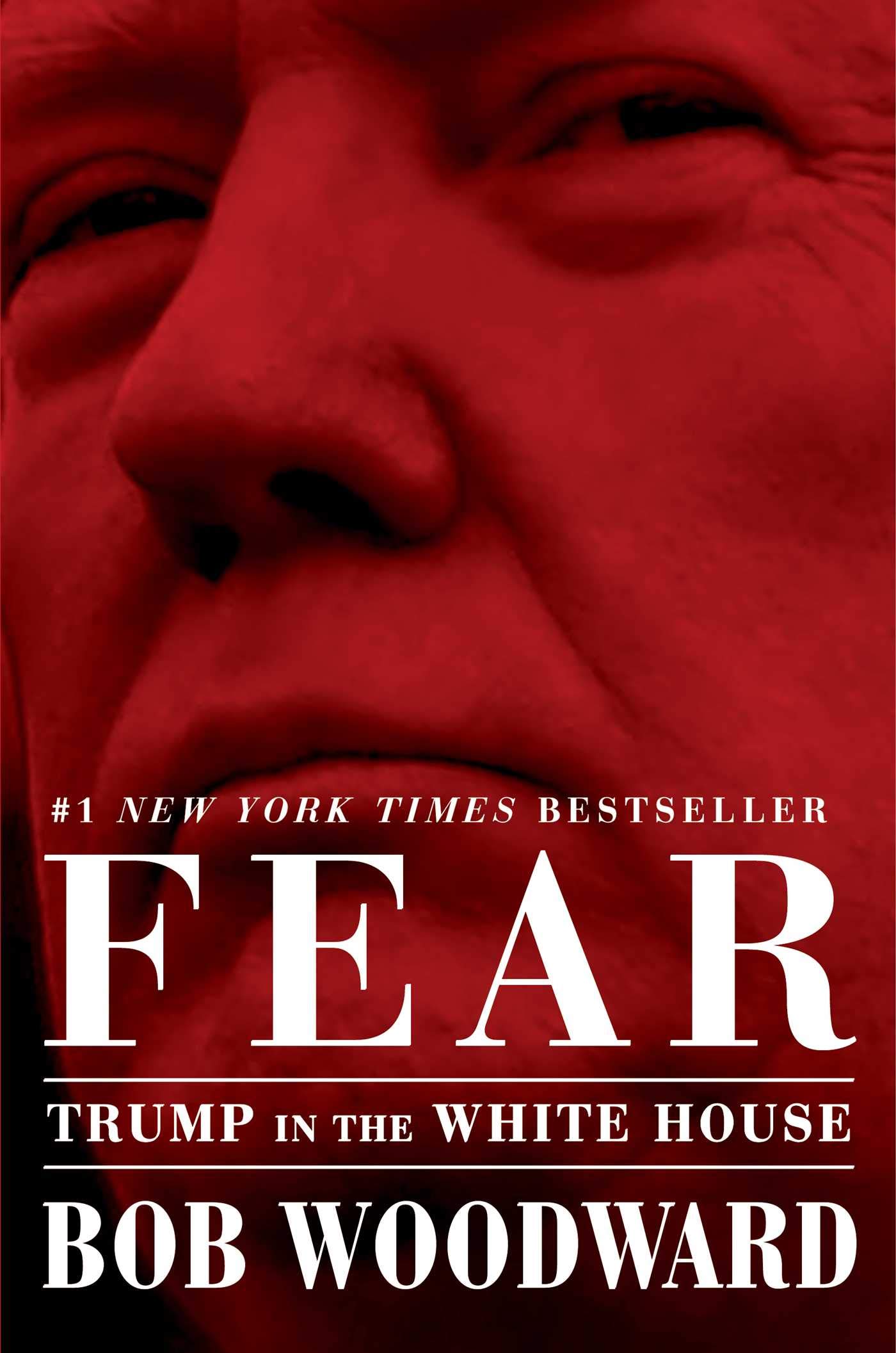

Bob Woodward may have achieved the greatest publishing success of his career with Fear, the inside story of turmoil inside the administration of President Donald Trump. Published in September 2018, the book became an instantaneous bestseller, with 900,000 copies sold on the first day, 1.1 million in the first week. The fastest-selling book in the history of its publisher, Simon & Schuster, it immediately topped The New York Times bestseller list, and within eight days of publication was already in its tenth printing.

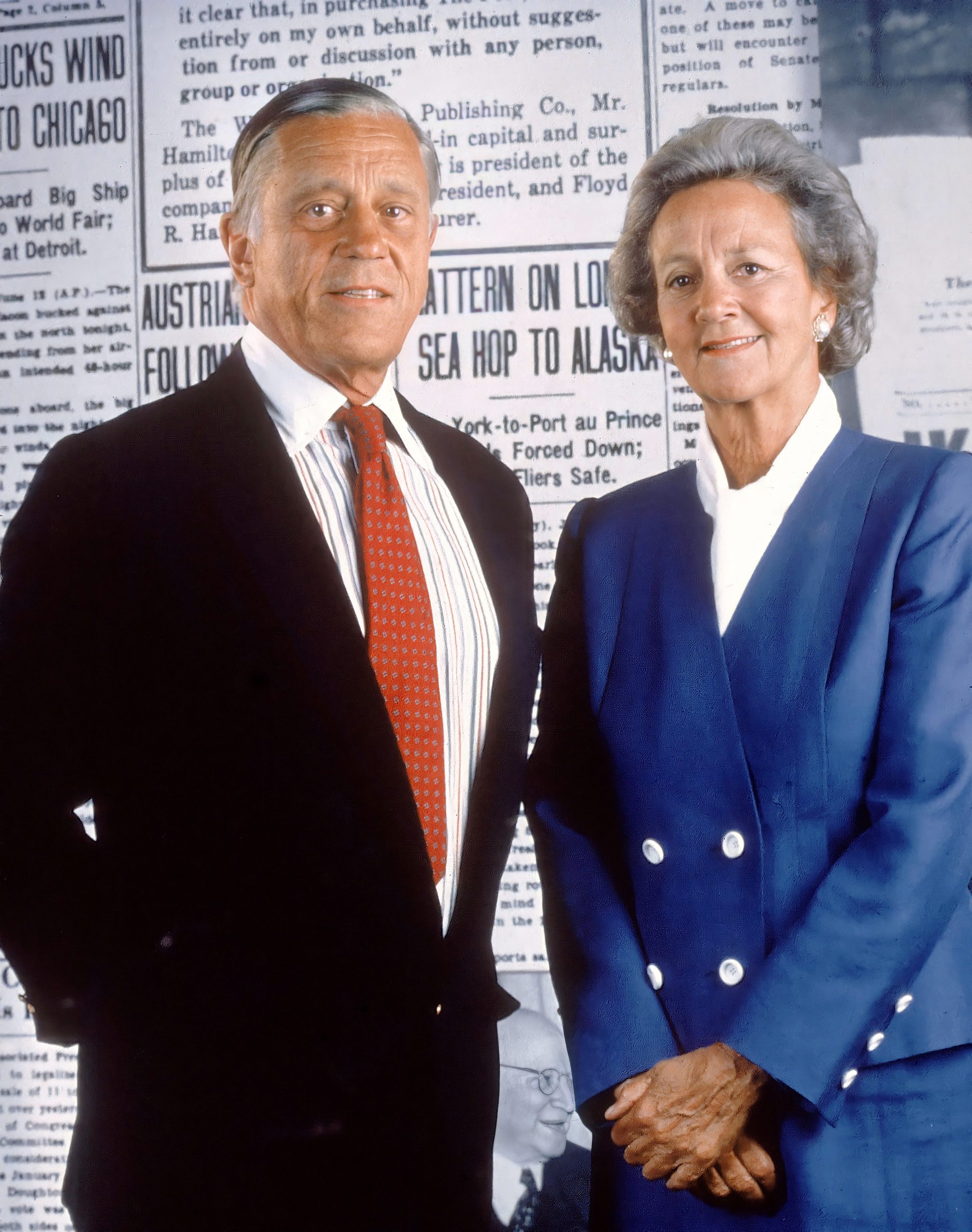

Now an associate editor at The Washington Post, for several years Bob Woodward oversaw the paper’s special investigative projects. Bob Woodward has two daughters, Tali and Diana. He lives in Washington, D.C. with his wife, Elsa Walsh, a writer for The New Yorker. The American Academy of Achievement’s interview with Bob Woodward is combined with an interview with his longtime editor and mentor, Ben Bradlee (1921-2014).

“I called my father and said I’m not going to law school, but have this job at a newspaper he had never heard of. And my father said probably the severest thing he has ever said to me. He said, ‘You’re crazy.’ So he didn’t think it was a good idea.”

Fresh out of the Navy, Bob Woodward washed out in his first attempt to work for The Washington Post, and went to work for a tiny suburban weekly. A year later, he was back at the Post, and at age 29 found himself in the middle of one of the biggest stories of the century.

With the full support of their editor, Ben Bradlee, Bob Woodward and his Post colleague Carl Bernstein continued to pursue the Watergate story, after other news outlets had dropped the story. In the end, the Watergate scandal brought down a president and made Bob Woodward the most famous investigative reporter in America. He is now Assistant Managing Editor of the Post, and has written nearly a dozen bestselling books.

(The Academy of Achievement interviewed both Bob Woodward and Ben Bradlee, the Executive Editor of The Washington Post, on May 1 during the 2003 International Achievement Summit in Washington, D.C. Their interviews are combined here.)

Mr. Woodward, can you tell us about the night you first got that phone call about a break-in at the Watergate?

Bob Woodward: June 17, 1972. I had worked for the Post for nine months. They had this — it looked like a local burglary at the Democratic Headquarters, a police story. I covered the night police beat. It was a Saturday morning, I think the summer. Editors looked around and thought, “Who could we call in? Who would be dumb enough to work on this story on a Saturday morning?” And they thought of me immediately. So I went to work with about seven or eight other people, including Carl (Bernstein), and I went to the arraignment of the five burglars, and the judge wanted to know where one of them worked, and he was mumbling. He wouldn’t say. Kind of going, “CIA.” And the judge said, “Where?” And he went, “CIA.” And the judge said, “Speak up. Where do you work? Where did you work?” And he went, “CIA, Central Intelligence Agency.” And I know my reaction was one of “Oh! This is not your average burglary.”

Why did they think of you? You mentioned that you had been at the Post for nine months. How long had you been at the previous paper?

Bob Woodward: One year exactly. So I did not have two years’ experience. I was the lowest-paid reporter at The Washington Post, because they would only give you credit with the Newspaper Guild if you had worked for a daily, and I had worked for a weekly.

What an incredible jump in your fortunes as a journalist, from one year on a little suburban paper to The Washington Post. How did you do that?

Bob Woodward: I was not married at the time and loved being free to do something. I worked quite hard, did a number of stories that the Post and The New York Times picked up. The Post is a very competitive institution, and I think that was the main reason.

How old were you at the time of that break-in?

Bob Woodward: Twenty-nine.

Mr. Bradlee, when did it become clear to you that the Watergate break-in was something more than a simple burglary?

Ben Bradlee: Probably the first or second day, really. It was strange. You had a lot of Cuban or Spanish-speaking guys in masks and rubber gloves, with walkie-talkies, arrested in the Democratic National Committee Headquarters at 2:00 in the morning. What the hell were they in there for? What were they doing?

The follow-up story was based primarily on their arraignment in court, and it was based on information given our police reporter, Al Lewis, by the cops, showing them an address book that one of the burglars had in his pocket, and in the address book was the name “Hunt,” H-u-n-t, and the phone number was the White House phone number, which Al Lewis and every reporter worth his salt knew. And when, the next day, Woodward — this is probably Sunday or maybe Monday, because the burglary was Saturday morning early — called the number and asked to speak to Mr. Hunt, and the operator said, “Well, he’s not here now; he’s over at” such-and-such a place, gave him another number, and Woodward called him up, and Hunt answered the phone, and Woodward said, “We want to know why your name was in the address book of the Watergate burglars.” And there is this long, deathly hush, and Hunt said, “Oh, my God!” and hung up. So you had the White House. You have Hunt saying “Oh, my God!” At a later arraignment, one of the guys whispered to a judge. The judge said, “What do you do?” and Woodward overheard the words “CIA.” So if your interest isn’t whetted by this time, you’re not a journalist.

What a story.

Ben Bradlee: It’s a good story. Not bad, as they say, and what legs! You have kids who weren’t born at that time doing term papers on it at colleges and high schools.

Mr. Woodward, once you heard one of the burglars say he worked for the CIA, where did you take it from there?

Bob Woodward: Is the CIA connected to this? Well, it turns out a lot of CIA people were, and they tried to use the CIA to cover up the FBI investigation, but they never pinned it on the CIA. It was a White House operation. So you would not go from the CIA to the White House instantly, but within several days, through the work of another reporter, we learned there was this cryptic entry in the address books of two of the five burglars that very simply said “H. Hunt – W. House.” So I called the White House and asked for Mr. Hunt, and he came on, and I said, “Why is your name in the address books of these two burglars who were caught in the Democratic Headquarters?” And he screamed out, “Good God!” and hung up the phone. And there was a sort of, as I have said, “I am packing my bags” quality to his voice that didn’t tell you everything you needed to know but certainly got you focused on, you know, this is interesting now. And it turned out he had worked for the CIA for years, had been working in the White House as a consultant to Chuck Colson, who was then Nixon’s hatchet man.

So this was over a period of days, I take it, that it got interesting.

Bob Woodward: Yes, and each week it got more and more interesting. As a colleague of ours at the Post, Bill Greider, wrote the day they disclosed the secret taping system in the White House. I think the lead of his story was, “Will the wonders of Watergate never cease?”

Mr. Bradlee, there is a scene early in the book and the movie, All the President’s Men, in which you criticize Woodward and Bernstein for their approach to a story about E. Howard Hunt, and his interest in Chappaquiddick and Ted Kennedy. What was that about? Hunt had been studying Ted Kennedy and checked books out of the library.

Ben Bradlee: A book had been taken out of the library. When we found out who had taken it out, it was Hunt, and everybody said, “What the hell is Hunt doing taking a book on Teddy Kennedy. Why is he interested in that?” But every Republican in the country was interested in Chappaquiddick, and not a few Democrats, so I said, “Find out what the hell he took it out for. Maybe we have a story and maybe we don’t.”

So all the while that this was coming out, you were being very careful that there was enough confirmation of these things?

Ben Bradlee: We were being very careful. As the stakes increased, and as the White House looked more and more threatened, and Nixon himself looked more threatened, and his office became threatened, we just were determined that we weren’t going to make any silly mistake.

Were there any mistakes?

Ben Bradlee: One.

We made one mistake in a story in which we said that — Woodward and Bernstein said — that there was a slush fund of $300,000 set up in the Committee to Re-elect the President, and it was controlled by Haldeman, and that one of the witnesses had testified to that slush fund to the grand jury investigating Watergate. I have forgotten which one it was. But the following morning, Dan Schorr of CBS — we saw on CBS Morning News— shoved a microphone in front of this guy and said, “The Post says you did this. Did you?” and he said, “No.” And the whole town shook, as far as I’m concerned, because that was the first time we had been accused of getting anything wrong. What it turned out was that the question hinged on whether or not he had told that to the grand jury, and since he hadn’t, he was able to say “No.” He wasn’t asked was there a slush fund, which, of course, there was. It turned out that he hadn’t been asked, and that interested us a great deal, because if the prosecution wasn’t asking him those interesting questions, that suggested that there was a reason they weren’t, and the reason might be that they were trying to cover it up. Anyway, it took two days, and we got confirmation that there was, and in fact there was a slush fund of $750,000. So that gave hope to the Republicans, and of course, all of the Republican spokesmen had a field day beating us upside the face over that, but it didn’t last very long. Thank God.

This was a long process.

Ben Bradlee: Four hundred stories about Watergate in The Washington Post Four hundred in two years and two months.

Mr. Woodward, there were mistakes made during Watergate, you have said in the book. What were some of the mistakes?

Bob Woodward: We accused some people of things they didn’t do that were based on some reports, written reports. We said Haldeman had controlled the secret fund, according to the Grand Jury testimony of the Nixon Committee treasurer, and he had not testified to that. The story was true, but he had never testified to it because they never asked him.

Mr. Bradlee, at what point did you get the inkling that the Oval Office was involved? Do you remember?

Ben Bradlee: Well, right away, with Hunt’s name and the White House telephone number in there.

And Nixon himself?

Ben Bradlee: Nixon himself? I can’t remember, but there were so many. Haldeman? Yes. Ehrlichman? Yes. All of the guys who later went to jail. Mitchell? Yes. It was inconceivable that Nixon wasn’t. But of course, that all became academic when the tapes came out. It came out in the Ervin Committee hearings in the Senate. We were told that before we could write it, but yes, we knew it. It was so important. The whole reputation of the paper was hanging on that by the time. There was an election on in ’72, and most of the rest of the country was saying, “The Post is just playing politics,” and all that stuff.

Mr. Woodward, at what point did you realize that President Nixon was implicated in this?

Bob Woodward: Quite late. We were reporting on the President’s men, and the White House people, the Attorney General, John Mitchell, people in the Nixon campaign, the Committee to Re-Elect the President, and the focus was not Nixon. It was only later, when Dean testified, and the tapes came out, that it was quite clear that not only was Nixon involved, he was in charge of the cover-up.

And that this wasn’t just a cover-up of a burglary. For example, talk about how it affected Muskie.

Bob Woodward: That’s right.

That was the key. The important discovery for Carl and myself was that Watergate wasn’t isolated. There were other burglaries. There was the whole intelligence-gathering apparatus. There were spies in all the Democratic candidates’ campaigns that had been planted and paid by the Nixon campaign. That they would sabotage campaigns. Things that seemed to be simple and innocuous but were quite devastating, false press releases, and accusing people of various activity and so forth, and a kind of sowing the seeds of discord.

There was a letter forged, saying that Muskie had made some disparaging remark about Canadians, and Muskie got very upset. It was never conclusively established that this had been done by the Nixon campaign, but one of the people in the White House acknowledged to one of our reporters that he had written it. Muskie, in the emotion of the campaign, was trying to explain what had gone on. There had been some disparaging remarks made elsewhere about his wife, and he cried, in the snow, in New Hampshire, standing on the back of a flatbed truck, and it’s generally believed that was the end of his candidacy. And of course, Muskie was going to be the strong candidate against Nixon.

It seems to me that to be a topnotch investigative journalist, you have to have a lot of guts in order to question some of these things.

Bob Woodward: No. The guts are supplied by the owners of the newspaper and the editors. They have always backed what I do. I’m out there doing it, and if there’s pressure or debate or controversy, they’re absorbing that pressure. Certainly during Watergate, it didn’t get transmitted to Carl Bernstein or myself through them. They said, “Keep going. Get to the bottom of it.”

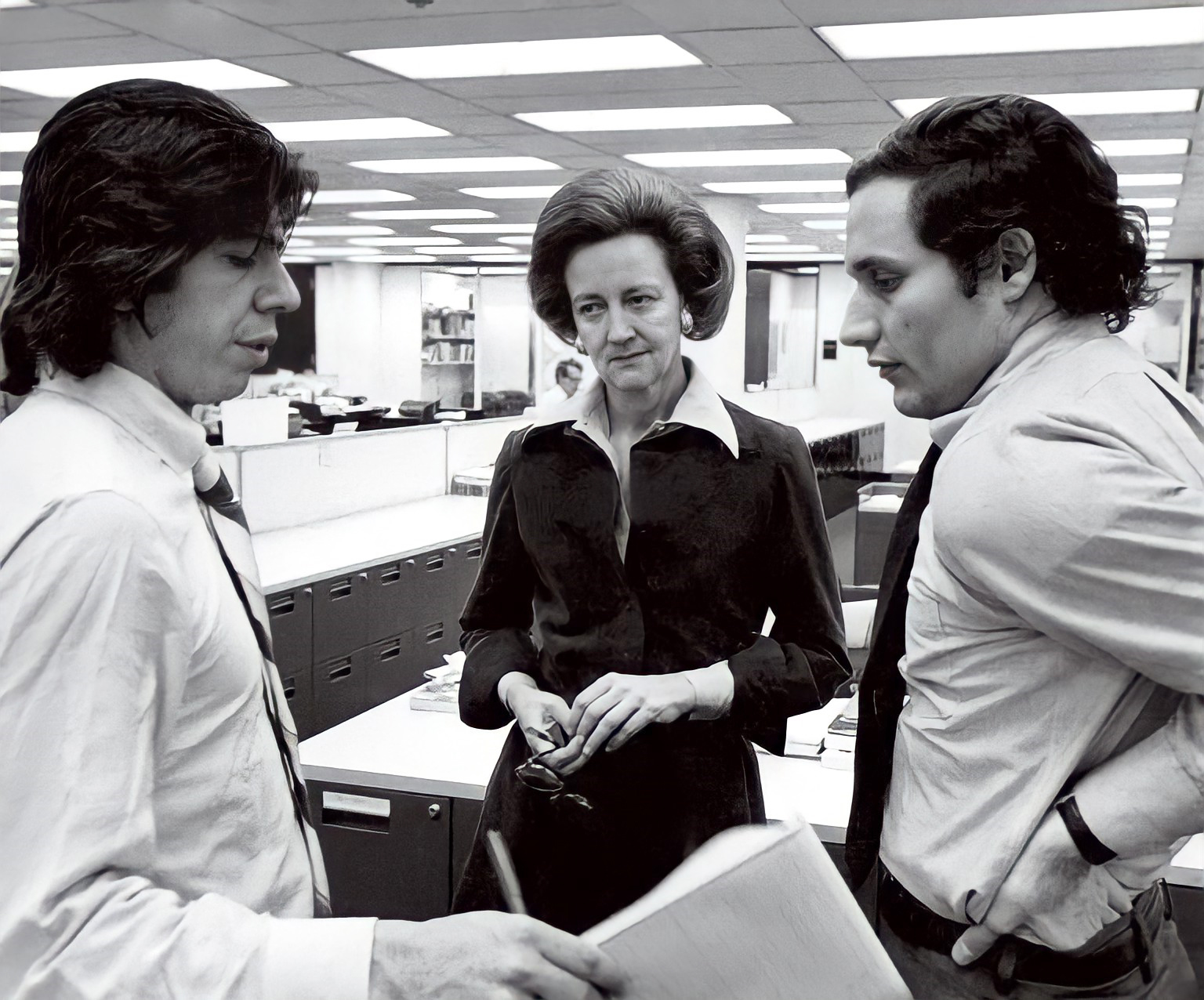

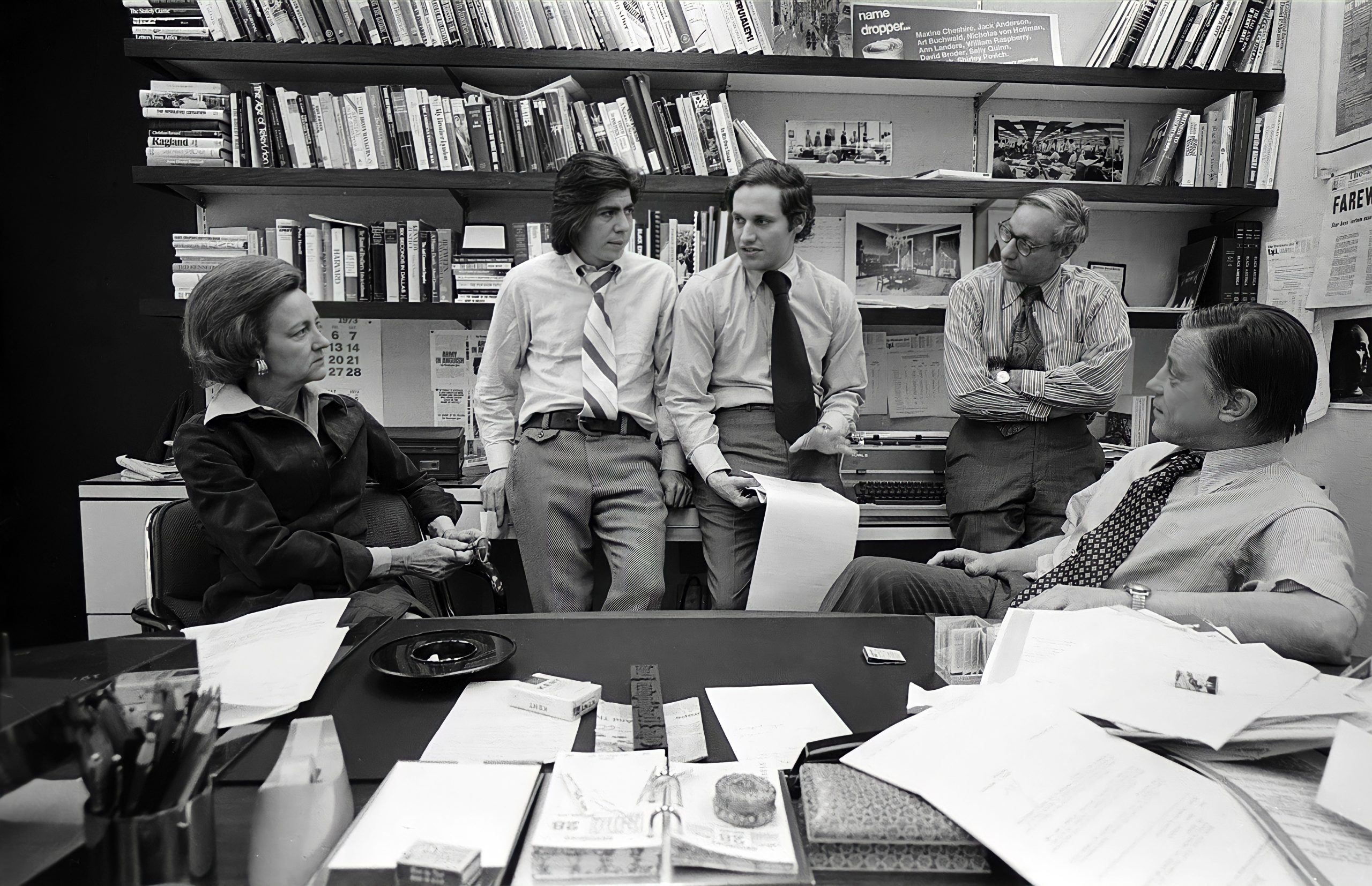

Didn’t you have a chat with the Post‘s publisher, Katharine Graham, in the midst of all of this?

Bob Woodward: About six months after Watergate, after Carl and I had written many of — almost all of — our main stories, she called me up for lunch. And she had a style of “I want to know what’s going on. I want to offer some ideas. Kind of parse it out.” But she wasn’t the editor. She was the publisher. She had what I call “Mind on, hands off.” She was intellectually engaged in the news, but her hands were not directing, not saying, “Investigate this, don’t investigate that, give the emphasis here.” That was Bradlee and the editors’ job. But she was quite curious, quite well-informed, plugged in. And she said, “When will we know the full story of Watergate? When will all the truth come out?” Quite optimistically. She posed this, almost suggesting that it was inevitable. And my reaction was, I told her, “Well, Carl and I think that it will never come out, that Nixon and his White House are so good at obscuring things, of sealing off information, preventing disclosure, that we’ll never know.” She looked at me quite stricken and said, “Never? Don’t tell me never.” And I remember thinking and feeling quite motivated that she was saying the standard here is the bar is quite high. “Don’t tell me ‘never.’ Get to the bottom of it.” That your resources, the resources of the newspaper, should be directed at completing this story, getting the full tale, if you would. And it in many ways is, I think, the principle under which she and her son, Don Graham, tried to run The Washington Post. “Don’t tell me ‘never.’ Don’t let things elude us. It’s our job to figure them out.”

Mr. Bradlee, it’s important to remember that Nixon was re-elected during this period.

Ben Bradlee: By an overwhelming margin, as we were reminded so often.

But you decided to “back the kids.”

Ben Bradlee: I backed the kids.

That’s a quote from the movie and the book. What made you “back the kids,” Woodward and Bernstein?

Ben Bradlee: Because the kids were right. They were not hard to support, these young reporters, because they were right. Every time the White House denied something, the evidence became clear that it was the White House that was lying. First, the spokesmen at the White House, Ziegler and some of those guys, and next the Attorney General, and Chuck Colson, all of those people, the White House aides, were lying. Robert Dole, and Dole’s successor as the chairman of the Republican Party, George Bush the first. These guys lied because they didn’t know the truth, and they couldn’t believe that they were being lied to.

Nixon didn’t last too long in that second term. Where were you when he resigned, and what were your feelings?

Ben Bradlee: I was at The Washington Post, and I couldn’t believe it. I mean, I believed it, because it was — I knew it was coming. I really — we knew it, we knew it, we knew it, but we couldn’t — we were being told by the people who were telling us that if we publish it, he’ll change his mind and won’t resign! So we started phrasing it “close to resignation,” and “debating resignation,” and then, finally, we learned that — I think he was going to do it at nine o’clock at night, or eight o’clock at night. He resigned. Well, I was down there. Where the hell? I mean, I lived in that place for those periods. And we were so scared that we were going to — by this time, we knew that the front page was going to be a historical document. It was going to be reproduced in the history books, and we wanted to be sure that we got it right, and be sure that some — there wasn’t a typo. In those days, you worried terribly about typos. We wanted to be sure that it wasn’t sabotaged in some way by, you know, printers slipping in the “F” word or something like that that was going to screw it up. And we had to be sure the headline was right. We had to be sure. Just — it was terribly, critically important that we do it right and that we not brag, not seem to be bragging, and that we didn’t allow any television in there for days.

I was worried about the Post‘s image of all of this, and that there would be a segment of society who said, you know, “They were out to get him, those bastards, and they got him.” And it was going to be — we were just very careful. We had such good sources. One of the sources I can now reveal — I mean, I have talked about — was Senator Goldwater, who was a great friend of my wife’s family, and I used to talk to him all the time. I’d have drinks with him early — all of late July and early August. And he would be going over to the White House to give Nixon the news that he didn’t have any — his support in the Senate was eroding. And he was the one who said that. He told me first that he was going to resign, wasn’t sure when, and for God’s sake don’t write it as hard, because he won’t. So we were terribly worried, and we didn’t — it’s a big newspaper and a lot of people in it, and you can’t control all of them even if you wanted to. So we tried to just keep people out of the building. We didn’t allow any television people in. We didn’t allow television in for six months, I don’t think. And when Redford wanted to film the movie in the Post, we told him he couldn’t. He wanted to film it from 3:00 in the morning until 8:00 in the morning, and we just told him it was not possible.

Mr. Bradlee, what were your emotions when Nixon resigned?

Ben Bradlee: That we had really done a really good job. That the difficulties they put up to prevent the truth from coming out had been overcome. That really is what we’re all about. Let’s be sure for the record to say that it wasn’t just the Post. The Post played a critical role in the beginning, and Woodward and Bernstein came in at critical moments. They were the first to reveal the tapes, and they were always ahead of the curve, but there was a lot of great reporting done by other people, Sy Hersh, the Los Angeles Times, they all did really good work.

Mr. Woodward, tell us what it felt like to you personally when Nixon stepped down.

Bob Woodward: We had done some of the early stories, that it led to the Senate Watergate Committee, led to the House Judiciary Committee and impeachment investigation. Special Prosecutor Cox and Jaworski investigated this, put lots of people in jail. The Supreme Court ordered the president to turn over his tapes, which really sunk him — the “smoking gun” tapes — at the end. So I had just a sense that — we had done some of the first work on this — that any suggestion that we had caused it, or brought down a president, was a stretch, to say the least, and not factual. That we had done stories, but it is a process of the judiciary, the Congress, the Supreme Court, that led to Nixon’s demise. But then, of course, if you think about it, Nixon is the one who did himself in. The piston driving the Nixon administration was hate. Nixon was a full-blown hater, and if you listen to the tapes, it’s chilling and frightening.

Paranoid too. Right?

Bob Woodward: Well, paranoid, and…

He wanted to use the presidency as an instrument of personal revenge, to settle scores, too often, and that’s not what the presidency is about. And what’s sad about the Nixon presidency is not just the criminality and abuse of power, but the simple truth, to the best of my knowledge at this point, on those tapes no one ever says what would be good, what would be right for the country, what would be best for the country, which of course is what a president is supposed to do. It seemed to always be about Nixon. “How does this affect me, Nixon, the president? How do I pay someone back, either good or bad, for what they have done to me?”